“On a Night Like This” Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

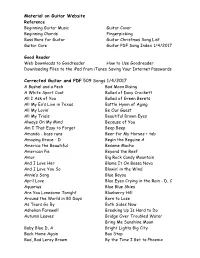

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Sample Script

Follow That Star Primary Script by Gawen Robinson & Stephen Robertson 6/031013/3 ISBN: 978 1 84237 102 2 Published by Musicline Publications P.O. Box 15632 Tamworth Staffordshire B78 2DP 01827 281 431 www.musiclinedirect.com Licences are always required when published musicals are performed. Licences for musicals are only available from the publishers of those musicals. There is no other source. All our Performing, Copying & Video Licences are valid for one year from the date of issue. If you are recycling a previously performed musical, NEW LICENCES MUST BE PURCHASED to comply with Copyright law required by mandatory contractual obligations to the composer. Prices of Licences and Order Form can be found on our website: www.musiclinedirect.com CONTENTS Cast List ................................................................................................................................ 2 Speaking Roles By Number Of Lines ................................................................................ 3 Cast List In Alphabetical Order (With Line Count) ........................................................... 4 Characters In Each Scene ................................................................................................... 5 List Of Properties ................................................................................................................. 6 Production Notes ................................................................................................................. 7 Scene One .......................................................................................................................... -

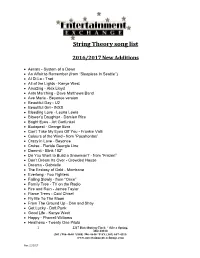

String Theory Song List

String Theory song list 2016/2017 New Additions Aerials - System of a Down An Affair to Remember (from “Sleepless In Seattle”) Al Di La - Trad All of the Lights - Kanye West Amazing - Alex Lloyd Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band Ave Maria - Beyonce version Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful Girl - INXS Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blower’s Daughter - Damien Rice Bright Eyes - Art Garfunkel Budapest - George Ezra Can’t Take My Eyes Off You - Frankie Valli Colours of the Wind - from “Pocahontas” Crazy in Love - Beyonce Cruise - Florida Georgia Line Dammit - Blink 182* Do You Want to Build a Snowman? - from “Frozen” Don’t Dream Its Over - Crowded House Dreams - Gabrielle The Ecstasy of Gold - Morricone Everlong - Foo Fighters Falling Slowly - from “Once” Family Tree - TV on the Radio Fire and Rain - James Taylor Flame Trees - Cold Chisel Fly Me To The Moon From The Ground Up - Dan and Shay Get Lucky - Daft Punk Good Life - Kanye West Happy - Pharrell Williams Heathens - Twenty One Pilots 1 2217 Distribution Circle * Silver Spring, MD 20910 (301) 986-4640 *(888) 986-4640 *FAX (301) 657-4315 www.entertainmentexchange.com Rev: 11/2017 Here With Me - Dido Hey Soul Sister - Train Hey There Delilah - Plain White T’s High - Lighthouse Family Hoppipola - Sigur Ros Horse To Water - Tall Heights I Choose You - Sara Bareilles I Don’t Wanna Miss a Thing - Aerosmith I Follow Rivers - Lykke Li I Got My Mind Set On You - George Harrison I Was Made For Loving You - Tori Kelly & Ed Sheeran I Will Wait - Mumford & Sons -

Chanting the Opening Line of Psalm 118 While Looking

1/31/21 Scene 1 Andrew: (chanting the opening line of Psalm 118 while looking up with arms widespread, shortly after Jesus and three disciples leave them) “Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good, his love is everlasting.” Philip: (seated, briefly covering his ears, interrupting) “Hey, Andrew! Enough’s enough! We chanted all the way up here! I need some rest—it’s been a long day.” Andrew: “Oh, all right. But, I’m still on a high. It’s been the most marvelous Passover I’ve ever had! My cup overflows!” Philip: “Oh, so that’s what’s got into you! Not even a sip of wine for weeks, and tonight we had four cups! You’re drunk . .” Andrew: “No way! At least not on wine. I’m still feeling the love from Jesus. It just poured out of him in the Upper Room. Don’t tell me you didn’t feel it, too, Philip?” Philip: (thinking, then nodding) “Yes, you’re right there. I’ll admit that when we were around the supper table, the wonder of Passover really came home to me. Better even than the first time I was the child who got to ask why this night is different from all other nights.” Andrew: “How do you mean?” Philip: “Well, when my father answered, he was only reciting the words of the Haggadah scroll. But, when Jesus was telling the story of how our people came up out of slavery in Egypt, not reading from a scroll, I had a strange feeling he was describing what he had seen with his very own eyes. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

CHRISTMAS SEASON PIECES the Levels of Difficulty Are from 1 (Easy) to 5 (Difficult)

CHRISTMAS SEASON PIECES The levels of difficulty are from 1 (easy) to 5 (difficult). Each piece bears a number. A title bearing an asterisk indicates that a recording is available upon request. Plus or minus signs mean more or less difficulty than the number. A CHILD’S CHRISTMAS PRAYER (Unison Voices/piano) is a plaintive piece that can touch one’s heart and cause him/her to interpret the words and the situation of a host of children at Christmas time. If one looks carefully at all three voices, s/he will see that they all have the same melody. And now I lay me down to sleep; I pray the Lord my soul to keep. If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take. If Christmas comes, and I am gone, I pray its spirit lingers on. If I am in the angel's choir, I'll sing and play my heavenly golden lyre. Merry Christmas to you all. WD Ranges are: Sopranos, E1-f2; Alto, a-c2 (3:00) #3 MED. THE BARNYARD CHRISTMAS ALERT: (Sopranos 1 & 2 and Alto) presents the animal’s reaction to Christmas Eve. Although the music seems to be three different parts, it is actually the same melody, with different rhythms in each part. Children or adults can enjoy this piece from its sound and from the way the music is put together. The duck told the chicken and the chicken told the mouse, “There’s an evergreen tree in the farmer’s house!” The mouse told the cat to go and tell the bat that they all should get along because of that. -

JELLYBEAN JAM Songlist Medleys

JELLYBEAN JAM songlist Medleys (Please note Medleys cannot be broken down in form) 80s- Born To Be Alive, Shake Your Groove Thing, Don’t Leave me This way, Jessie’s Girl, Video Killed The Radio Star, Its Raining Men, You Spin me Round, Love Shack, We Built This City, My Sharona 80s2- Girls Just Wanna Have Fun, Venus, Just Can’t Get Enough, Xanadu, Hungry Like The Wolf , Funky Town. Chicks- Holiday, Step Back in Time, Lets Hear It for the Boy, Express Yourself, Finally, Better the Devil You Know Disco 1 - Blame it on the Boogie, Disco Inferno, Car Wash, Celebration, We are Family, Le Freak. Disco 2 - Jungle Boogie, Upside Down, Can’t Stand the Rain, Get down on it, Funky Music, Everyone's a Winner, Can’t Get Enough of Your Love, Tragedy, Lady Marmalade, Love Is in the Air, Kung Fu Fighting Disco 3 – Give It Up, Long Train Running, That’s the Way I like It, If I Can’t Have You, Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough, Can You Feel It Disco 4 - I will survive, You should be dancing, Got To be real, Young Hearts Run Free, Do Ya think I'm Sexy, September, Hot Stuff, Boogie Wonderland. Jacko- Thriller, Shake Your Body, Billie Jean, Rock with You, Black or White, Wanna Be Starting Something, Bad Abba- Dancing Queen, SOS, Money Money Money, Ring Ring, Mamma Mia Latin – I Go To Rio, Conga, Hot Hot Hot, Copacabana, The Love Boat Mambo- Tequila, Yeh Yeh, Mambo no 5 Motown - Uptight, can’t help myself, same ole song, dancing in the street, aint too proud to beg, joy to the world, get ready , stop, its my party, never can say good bye Movie- Flashdance, fame, -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Allegheny Ukes Club Songbook Vol. 2

Songbook 2 Songbook 2 Table of Contents 1. Aloha ‘Oe 31. La Bamba 2. Back Home Again 32. Lava 3. Back to the Island 33. Let it Be 4. Bad Bad Leroy Brown 34. Loco-Motion 5. Birds and the Bees 35. Margaritaville 6. Bye Bye Love 36. Moonlight Bay 7. California Girls 37. Morning Has Broken 8. Can’t Buy Me Love 38. Oo-de-lally 9. Chatanooga Choo Choo 39. Pearly Shells 10. City of New Orleans 40. Peepers 11. Cowboy Rides Away, The 41. Ragtime Cowboy Joe 12. Crocodile Rock 42. Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head 13. Daydream Believer 43. Rock This Town 14. Do You Believe in Magic 44. Rockin’ Robin 15. Do You Wanna Dance? 45. Sea Cruise 16. Dock of the Bay, The 46. Sentimental Journey 17. Don’t Stop Believin’ 47. Sing 18. Down on the Corner 48. Sloop John B., The 19. Dust in the Wind 49. Summertime Blues 20. Fields of Athenry 50. Swingin’ on a Star 21. For Baby (For Bobby) 51. Take It Easy 22. Froggy Went a Courtin’ 52. That’ll Be the Day 23. Fun, Fun, Fun 53. Unchained Melody 24. Happy Wanderer 54. Under the Bamboo Tree 25. Home on the Range 55. Waltzing Matilda 26. Hukilau Song 56. Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow 27. In the Good Old Summertime 57. Wonderful World 28. Jolene 58. Yellow Bird 29. Kiss the Girl 59. Yes Sir, That’s My Baby 30. Kokomo 60. You Are the Sunshine of My Life Starting Aloha ‘Oe Note – E 2/2 C G A-lo-ha ‘oe, a-lo-ha ‘oe D7 G G7 e-ke o-na o-na no-ho i-ka li-po C G One fond embrace a ho-‘i a-‘e au, D7 G C G Until we meet again C G Farewell to thee, farewell to thee D7 G G7 Thou charming one who dwells among the bowers. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun