The Year That Was

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Writing Life Twelve New Zealand Authors DEBORAH SHEPARD

Intelligent, relevant books for intelligent, inquiring readers The Writing Life Twelve New Zealand Authors DEBORAH SHEPARD CANDID CONVERSATIONS WITH 12 WRITERS WHO HELPED SHAPE NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE A unique, candid and intimate survey of the life and work of 12 of our most acclaimed writers: Patricia Grace, Tessa Duder, Owen Marshall, Philip Temple, David Hill, Joy Cowley, Vincent O’Sullivan, Albert Wendt, Marilyn Duckworth, Chris Else, Fiona Kidman and Witi Ihimaera. Constructed as Q&As with experienced oral historian Deborah Shepard, they offer a marvellous insight into their careers. As a group they are now the ‘elders’ of New Zealand literature; they forged the path for the current generation. Together the authors trace their publishing and literary history from 1959 to 2018, through what might now be viewed as a golden era of publishing into the more unsettled climate of today. They address universal themes: the death of parents and loved ones, the good things that come with ageing, the components of a satisfying life, and much more. And they give advice on writing. The book has an historical continuity, showing fruitful and fascinating links $49.99 between individuals who have negotiated the same literary terrain for more than sixty years. To further honour them are magnificent photo portraits by CATEGORY: New Zealand Non Fiction distinguished photographer John McDermott, commissioned by the publisher ISBN: 978-0-9951095-3-7 for this project. eISBN: n/a ABOUT THE AUTHOR BIC: BGL, DSK, 1MBN BISAC: LCO020000, BIO007000 Deborah Shepard is an author, teacher of memoir, oral historian and film PUBLISHER: Massey University Press and art historian. -

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

Survival and Postcolonialism in Timothy Findley's Not Wanted On

Survival and Postcolonialism in Timothy Findley’s Not Wanted on the Voyage Riikka Antikainen University of Tampere School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies English Philology Pro Gradu Thesis May 2013 Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö ANTIKAINEN, RIIKKA: Survival and Postcolonialism in Timothy Findley’s Not Wanted on the Voyage Pro Gradu -tutkielma, 68 sivua Toukokuu 2013 Tarkastelen tutkimuksessani postkolonialismia ja selviytymistä Timothy Findleyn romaanissa Not Wanted on the Voyage (1984). Kyseistä romaania on tutkittu verraten vähän, vaikka eri tutkijat ovat päätyneet mitä erilaisimpiin tulkintoihin sen merkityksistä. Itse käsittelen sitä kanadalaisena, postkolonialistisena romaanina, jonka tärkeimmäksi teemaksi nousee selviytyminen. Lähtökohta tälle tulkinnalle on Margaret Atwoodin kirja Survival , josta on mahdollista löytää paljon yhtymiskohtia Findleyn romaaniin ja jonka sidon postkolonialistiseen käsitykseen itsestä ja toisesta. Keskeisimmät tutkimuskysymykseni ovat miksi selviytyä, miten selviytyä ja mitä tapahtuu selviytymisen jälkeen. Näiden kysymysten pohjalta pohdin tarinaa myös kolonialistisen ja postkolonialistisen ajan allegoriana. Keskityn tutkimuksessani ensin henkilöihin ja olosuhteisiin, jotka luovat uhreja ja pakottavat selviytymään, minkä jälkeen käsittelen yksittäisiä hahmoja erilaisina uhreina. Lopuksi pohdin selviytymistä ajan ja maailman, tai yhteiskunnan, kannalta pyrkien sitomaan Findleyn romaanin laajempaan, postkolonialistiseen viitekehykseen. -

A Remote Beginning: Poems, 1985, Daud Kamal, 0904675246, 9780904675245, Interim, 1985

A remote beginning: poems, 1985, Daud Kamal, 0904675246, 9780904675245, Interim, 1985 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1Qt2ZUq http://goo.gl/RiX10 http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&tn=A+remote+beginning%3A+poems&x=51&y=16 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1ZfaSmE http://thepiratebay.sx/torrent/73618217775426 http://bit.ly/WxL0LD The song of Lazarus , Alex Comfort, 1945, , 99 pages. The great siege of Fort Jesus an historical novel, Valerie Cuthbert, 1970, Mombasa (Kenya), 147 pages. A Year in Place , W. Scott Olsen, Bret Lott, 2001, Literary Collections, 219 pages. W. Scott Olsen and Bret Lott invited a dozen friends to consider one particular calendar month in the place they call home. The result is A Year in Place, a captivating. Recognitions , Daud Kamal, Jan 1, 1979, Poetry, 23 pages. A Library of the World's Best Literature - Ancient and Modern - Vol. VIII (Forty-Five Volumes); Calvin-Cervantes , Charles Dudley Warner, Jan 1, 2008, Literary Collections, 412 pages. Popular American essayist, novelist, and journalist CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER (1829-1900) was renowned for the warmth and intimacy of his writing, which encompassed travelogue. Nothing for tigers poems, 1959-1964, Hayden Carruth, 1965, Poetry, 85 pages. A Selection of Verse , Daud Kamal, Jan 1, 1997, Pakistani poetry (English), 51 pages. A Selection of Verse, is a carefully sifted volume that contains the best of Daud Kamal's work. Through honesty, the sheer tactility of the imagery and the zen-like focus he. Build a Remote-controlled Robot , David R. Shircliff, 2002, Technology & Engineering, 112 pages. Here are all the step-by-step, heavily illustrated plans you need to build a full-sized, remote- controlled robot named Questor--without any advanced electronic or programming. -

Language and Character in Keri Hulme's the Bone People

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2008 Creating Aotearoa through Discourse: Language and Character in Keri Hulme's The Bone People Sabryna Nicole Sarver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sarver, Sabryna Nicole, "Creating Aotearoa through Discourse: Language and Character in Keri Hulme's The Bone People" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 170. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/170 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATING AOTEAROA THROUGH DISCOURSE: LANGUAGE AND CHARACTER IN KERI HULME’S THE BONE PEOPLE by SABRYNA NICOLE SARVER (Under the Direction of Joe Pellegrino) ABSTRACT I will be looking at Keri Hulme’s novel the bone people as a postcolonial text. The beginning will explore the current conversations taking place about the importance of language(s) within texts that are deemed “postcolonial” as they relate to Hulme’s novel which is written in both Maori and English. Other important postcolonial ideas applicable to the text such as space, magical realism, and current postcolonial theory will be looked at. Previous criticism will also be examined. The final sections of this thesis will focus on Hulme’s three main characters separately: Joe, Kerewin, and Simon, and their places within and outside the text. -

The Edgar Mittelholzer Memorial Lectures

BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Edited and with an Introduction by Andrew O. Lindsay 1 Edited by Andrew O. Lindsay BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES - VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Preface © Andrew Jefferson-Miles, 2014 Introduction © Andrew O. Lindsay, 2014 Cover design by Peepal Tree Press Cover photograph: Courtesy of Jacqueline Ward All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission. Published by the Caribbean Press. ISBN 978-1-907493-67-6 2 Contents: Tenth Series, 1986: The Arawak Language in Guyanese Culture by John Peter Bennett FOREWORD by Denis Williams .......................................... 3 PREFACE ................................................................................. 5 THE NAMING OF COASTAL GUYANA .......................... 7 ARAWAK SUBSISTENCE AND GUYANESE CULTURE ........................................................................ 14 Eleventh Series, 1987. The Relevance of Myth by George P. Mentore PREFACE ............................................................................... 27 MYTHIC DISCOURSE......................................................... 29 SOCIETY IN SHODEWIKE ................................................ 35 THE SELF CONSTRUCTED ............................................... 43 REFERENCES ....................................................................... 51 Twelfth Series, 1997: Language and National Unity by Richard Allsopp CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD -

A Critical and Corpus Based Analysis of 21St Century Pakistani English Poetry

Orient Research Journal of Social Sciences ISSN Print 2616-7085 December 2019, Vol.4, No. 2 [312-320] ISSN Online 2616-7093 Metaphors We Live By: A Critical and Corpus Based Analysis of 21st Century Pakistani English Poetry Muhammad Riaz Gohar1, Dr. Muhammad Afzal2 & Dr. Behzad Anwar 3 1. Ph. D Scholar, Department English University of Gujrat, Gujrat 2. HOD, Department of Urdu GC Women University Sialkot 3. HOD, Department English University of Gujrat, Gujrat Abstract This study focuses on the critical evaluation of the most frequent metaphors in the Pakistani English poetry (PakEP) of 21st century. The poetic corpus includes the works of the maximum number of the poets from the whole of the country (sixty in number). They all belong to the post 9/11 time period. The corpus has thus two prime concerns as recency and representativeness. The researcher sets three objectives; first, which are the most frequent metaphors in the 21st C Pakistani English poetry; second, what the particular mood do these metaphors exhibit; third, to which school of poetry do these poets show their affiliation. With the use of AntConc3.2.1, the frequency, the concordance and the collocation of the most frequent metaphors have been discovered. Parallel to these, the description, interpretation and explanation of the metaphors have been conducted with the help of Fairclough’s (2000) model. The present study indicates that the recent English poetry of Pakistani young lot is thematically overwhelmed by love, heart and life. Secondly, despair and frustration are the moods of such poets in general. Thirdly, Pakistani English poetry is more akin to classicism and romanticism than modernism. -

Allegory in the Fiction of Janet Frame

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ALLEGORY IN THE FICTION OF JANET FRAME A thesis in partial fulfIlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Massey University. Judith Dell Panny 1991. i ABSTRACT This investigation considers some aspects of Janet Frame's fiction that have hitherto remained obscure. The study includes the eleven novels and the extended story "Snowman, Snowman". Answers to questions raised by the texts have been found within the works themselves by examining the significance of reiterated and contrasting motifs, and by exploring the most literal as well as the figurative meanings of the language. The study will disclose the deliberate patterning of Frame's work. It will be found that nine of the innovative and cryptic fictions are allegories. They belong within a genre that has emerged with fresh vigour in the second half of this century. All twelve works include allegorical features. Allegory provides access to much of Frame's irony, to hidden pathos and humour, and to some of the most significant questions raised by her work. By exposing the inhumanity of our age, Frame prompts questioning and reassessment of the goals and values of a materialist culture. Like all writers of allegory, she focuses upon the magic of language as the bearer of truth as well as the vehicle of deception. -

The Robert Burns Fellowship 2020

THE ROBERT BURNS FELLOWSHIP 2020 The Fellowship was established in 1958 by a group of citizens, who wished to remain anonymous, to commemorate the bicentenary of the birth of Robert Burns and to perpetuate appreciation of the valuable services rendered to the early settlement of Otago by the Burns family. The general purpose of the Fellowship is to encourage and promote imaginative New Zealand literature and to associate writers thereof with the University. It is attached to the Department of English and Linguistics of the University. CONDITIONS OF AWARD 1. The Fellowship shall be open to writers of imaginative literature, including poetry, drama, fiction, autobiography, biography, essays or literary criticism, who are normally resident in New Zealand or who, for the time being, are residing overseas and who in the opinion of the Selection Committee have established by published work or otherwise that they are a serious writer likely to continue writing and to benefit from the Fellowship. 2. Applicants for the Fellowship need not possess a university degree or diploma or any other educational or professional qualification nor belong to any association or organisation of writers. As between candidates of comparable merit, preference shall be given to applicants under forty years of age at the time of selection. The Fellowship shall not normally be awarded to a person who is a full time teacher at any University. 3. Normally one Fellowship shall be awarded annually and normally for a term of one year, but may be awarded for a shorter period. The Fellowship may be extended for a further term of up to one year, provided that no Fellow shall hold the Fellowship for more than two years continuously. -

PNZ 47 Digital Version

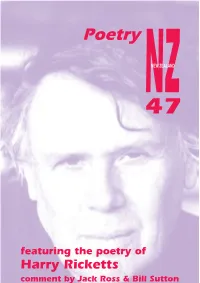

Poetry NZNEW ZEALAND 47 featuring the poetry of 1 Harry Ricketts comment by Jack Ross & Bill Sutton Poetry NZ Number 47, 2013 Two issues per year Editor: Alistair Paterson ONZM Submissions: Submit at any time with a stamped, self-addressed envelope (and an email address if available) to: Poetry NZ, 34B Methuen Road, Avondale, Auckland 0600, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo El Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Please note that overseas submissions cannot be returned, and should include an email address for reply. Postal subscriptions: Poetry NZ, 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo el Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Postal subscription Rates: US Subscribers (by air) One year (2 issues) $30.00 $US24.00 Two years (4 issues) $55.00 $US45.00 Libraries: 1 year $32.00 $US25.00 Libraries: 2 years $60.00 $US46.00 Other countries One year (2 issues) $NZ36.00 Two years (4 issues) $NZ67.00 Online subscriptions: To take out a subscription go to www.poetrynz.net and click on ‘subscribe’. The online rates are listed on this site. When your subscription application is received it will be confi rmed by email, and your fi rst copy of the magazine will then be promptly posted out to you. 2 Poetry NZ 47 Alistair Paterson Editor Puriri Press & Brick Row Auckland, New Zealand Palm Springs, California, USA September 2013 3 ISSN 0114-5770 Copyright © 2013 Poetry NZ 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „‘Kiwi’ Masculinities in New Zealand Short Stories“ Verfasserin MMag. phil. Maria Hinterkörner angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt : A 092 343 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Astrid Fellner [i] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “‘[New Zealand] is not quite the moon, but after the moon it is the farthest place in the world,’” said Sir Karl Popper (as quoted in KING 2003: 415), Austrian-New Zea- land-British philosopher; and ‘off the edge of the world’ in unlikely Kawakawa is where Friedensreich Hundertwasser built a colourful public toilet after having abandoned Austria for the sheep-crowded archipelago in the South Pacific. Little did I know about New Zealand as a country, as a people, as a nation and – above all – about how to pen a doctoral dissertation when I set out on this scien- tific journey a little while ago. At a very early stage of my doctoral endeavours, I knew my inquisitiveness could not be satisfied with the holdings at the University of Vienna, Austria, a country on the opposite side of the earth of the country’s lit- erature that I had chosen as subject of investigation. I was lucky enough to call Aotearoa/New Zealand my home for six months in 2009 – a sojourn that proved most fecund to my work, provided me with an abundance of motivation, and left me awe-inspired by the country’s inhabitants – scholars, fishermen, tattooists – its natural beauty and its rich and colourful culture. I was able to spend most of my time in the immense libraries of New Zealand’s universities and in conversation with scholars and authors who so very openly supported my work and provided answers where clarity had yet been missing. -

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award Crafting Aotearoa: Protest Tautohetohe: A Cultural History of Making Objects of Resistance, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust has immense in New Zealand and the Persistence and Defiance pleasure in presenting the 16 finalists in the 2020 Wider Moana Oceania Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the country’s Puawai Cairns Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Published by Te Papa Press most prestigious awards for literature. Damian Skinner Published by Te Papa Press Bringing together a variety of protest matter of national significance, both celebrated and Challenging the traditional categorisations The Trust is so grateful to the organisations that continue to share our previously disregarded, this ambitious book of art and craft, this significant book traverses builds a substantial history of protest and belief in the importance of literature to the cultural fabric of our society. the history of making in Aotearoa New Zealand activism within Aotearoa New Zealand. from an inclusive vantage. Māori, Pākehā and Creative New Zealand remains our stalwart cornerstone funder, and The design itself is rebellious in nature Moana Oceania knowledge and practices are and masterfully brings objects, song lyrics we salute the vision and passion of our naming rights sponsor, Ockham presented together, and artworks to Residential. This year we are delighted to reveal the donor behind the acknowledging the the centre of our influences, similarities enormously generous fiction prize as Jann Medlicott, and we treasure attention. Well and divergences of written, and with our ongoing relationships with the Acorn Foundation, Mary and Peter each.