Vitruvius Revisited: Palladio’S Canonical Orders in the First Book of “I Quattro Libri Dell’Architettura”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

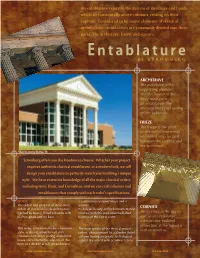

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

The Annual of the British School at Athens the Ionic Capital of The

The Annual of the British School at Athens http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH Additional services for The Annual of the British School at Athens: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Ionic Capital of the Gymnasium of Kynosarges Pieter Rodeck The Annual of the British School at Athens / Volume 3 / November 1897, pp 89 - 105 DOI: 10.1017/S0068245400000770, Published online: 18 October 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068245400000770 How to cite this article: Pieter Rodeck (1897). The Ionic Capital of the Gymnasium of Kynosarges. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 3, pp 89-105 doi:10.1017/S0068245400000770 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH, IP address: 130.133.8.114 on 02 May 2015 COIN TYPE OF ELIS, RESTORED. THE IONIC CAPITAL OF THE GYMNASIUM OF KYNOSARGES. (PLATES VL—Vm.) THE excavations of the British School at Athens, in the winters of 1896 and 1897, had the result of determining that the site, on which they were carried on, had been a burial ground previous to the sixth cen- tury B.C. and again after the third century, and that, in the meantime, it must have been covered by the Greek building, of which we laid bare the foundations. The plan of this building resembles that of a large gymnasium; the period of its existence coincides with that during which we know the gymnasium of Kynosarges to have existed, and the position of the site is such as the various mentions of Kynosarges by classic authors leads us to expect. -

4. Dressing and Portraying Isabella D'este

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/33552 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Dijk, Sara Jacomien van Title: 'Beauty adorns virtue' . Dress in portraits of women by Leonardo da Vinci Issue Date: 2015-06-18 4. Dressing and portraying Isabella d’Este Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua, has been thoroughly studied as a collector and patron of the arts.1 She employed the finest painters of her day, including Bellini, Mantegna and Perugino, to decorate her studiolo and she was an avid collector of antiquities. She also asked Leonardo to paint her likeness but though Leonardo drew a preparatory cartoon when he was in Mantua in 1499, now in the Louvre, he would never complete a portrait (fig. 5). Although Isabella is as well known for her love of fashion as her patronage, little has been written about the dress she wears in this cartoon. Like most of Leonardo’s female sitters, Isabella is portrayed without any jewellery. The only art historian to elaborate on this subject was Attilio Schiaparelli in 1921. Going against the communis opinio, he posited that the sitter could not be identified as Isabella d’Este. He considered the complete lack of ornamentation to be inappropriate for a marchioness and therefore believed the sitter to be someone of lesser status than Isabella.2 However, the sitter is now unanimously identified as Isabella d’Este.3 The importance of splendour was discussed at length in the previous chapter. Remarkably, Isabella is portrayed even more plainly than Cecilia Gallerani and the sitter of the Belle Ferronnière, both of whom are shown wearing at least a necklace (figs. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

Early Islamic Architecture in Iran

EARLY ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE IN IRAN (637-1059) ALIREZA ANISI Ph.D. THESIS THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 2007 To My wife, and in memory of my parents Contents Preface...........................................................................................................iv List of Abbreviations.................................................................................vii List of Plates ................................................................................................ix List of Figures .............................................................................................xix Introduction .................................................................................................1 I Historical and Cultural Overview ..............................................5 II Legacy of Sasanian Architecture ...............................................49 III Major Feature of Architecture and Construction ................72 IV Decoration and Inscriptions .....................................................114 Conclusion .................................................................................................137 Catalogue of Monuments ......................................................................143 Bibliography .............................................................................................353 iii PREFACE It is a pleasure to mention the help that I have received in writing this thesis. Undoubtedly, it was my great fortune that I benefited from the supervision of Robert Hillenbrand, whose comments, -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

Hellenistic Greek Temples and Sanctuaries

Hellenistic Greek Temples and Sanctuaries Late 4th centuries – 1st centuries BC Other Themes: - Corinthian Order - Dramatic Interiors - Didactic tradition The «Corinthian Order» The «Normalkapitelle» is just the standardization Epidauros’ Capital (prevalent in Roman times) whose origins lays in (The cauliculus is still not the Epudaros’ tholos. However during the present but volutes and Hellenistic period there were multiple versions of helixes are in the right the Corinthian capital. position) Bassae 1830 drawing So-Called Today the capital is “Normal Corinthian Capital», no preserved compared to Basse «Evolution» (???) of the Corinthian capital Choragic Monument of Lysikrates in Athens Late 4th Century BC First istance of Corinthian order used outside. Athens, Agora Temple of Olympian Zeus. FIRST PHASE. An earlier temple had stood there, constructed by the tyrant Peisistratus around 550 BC. The building was demolished after the death of Peisistratos and the construction of a colossal new Temple of Olympian Zeus was begun around 520 BC by his sons, Hippias and Hipparchos. The work was abandoned when the tyranny was overthrown and Hippias was expelled in 510 BC. Only the platform and some elements of the columns had been completed by this point, and the temple remained in this state for 336 years. The work was abandoned when the tyranny was overthrown and Hippias was expelled in 510 BC. Only the platform and some elements of the columns had been completed by this point, and the temple remained in this state for 336 years. SECOND PHASE (HELLENISTIC). It was not until 174 BC that the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who presented himself as the earthly embodiment of Zeus, revived the project and placed the Roman architect Decimus Cossutius in charge. -

Application of Color to Antique Grecian Architecture

# ''A \KlMinlf111? ^W\f ^ 4 ^ ih t ' - -- - A : ^L- r -Mi UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY .4k - ^» Class Book Volume MrlO-20M * 4 ^ if i : ' #- f | * f f f •is * id* ^ ; ' 4 4 - # T' t * * ; f + ' f 4 f- 4- f f -4 * 4 ^ I - - -HI- - * % . -4*- f 4- 4 4 # Hp- , * * 4 4- THE APPLICATION OF COLOR TO ANTIQUE GRECIAN ARCHITECTURE BY ARSELIA BESSIE MARTIN B. S. University of Illinois, 1909 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURAL DECORATION IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS fa 1910 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL June 4... 1910 190 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Viss .Arsel is Bessie ^srtin ENTITLED TM application of Color to antique Grecisn Architecture BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in Architectural Decoration In Charge of Major Work Head of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination 170372 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 * UHJCi http:V7afchive.org/details/applicationofcol00mart THE APPLICATION OF COLOR TO ANTIQUE GRECIAN ARCHITECTURE CONTENTS Page | INTRODUCTION 1 SECTION I - A Kistorioal Review of the Controversy .... 4 SECTION II - A Review of the Earlier Styles IS A » Egyptian B. Assyrian C. Primitive Grecian SECTION III - Derivation of the Grecian Polychromy ..... 21 SECTION IV - General Considerations and Influences. ... 24 A. Climate B. Religion C. Natural Temperament of the Greeks D. Materials SECTION V - Coloring of Architectural Members 31 Proofs classified according to monuments SECTION VI - The Colors and Technique of Architectural Painting SECTION VII - Architectural Terra. -

Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N

Exhibit A LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N. Sheridan Rd. Final Landmark Recommendation adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, August 7, 2014 CITY OF CHICAGO Rahm Emanuel, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is re- sponsible for recommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city per- mits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recom- mendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment dur- ing the designation process. Only language contained within a designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. 2 CAIRO SUPPER CLUB BUILDING (ORIGINALLY WINSTON BUILDING) 4015-4017 N. SHERIDAN RD. BUILT: 1920 ARCHITECT: PAUL GERHARDT, SR. Located in the Uptown community area, the Cairo Supper Club Building is an unusual building de- signed in the Egyptian Revival architectural style, rarely used for Chicago buildings. This one-story commercial building is clad with multi-colored terra cotta, created by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company and ornamented with a variety of ancient Egyptian motifs, including lotus-decorated col- umns and a concave “cavetto” cornice with a winged-scarab medallion. -

‐ Classicism of Mies -‐

- Classicism of Mies - Attachment Student: Oguzhan Atrek St. no.: 4108671 Studio: Explore Lab Arch. mentor: Robert Nottrot Research mentor: Peter Koorstra Tech. mentor: Ype Cuperus Date: 03-04-2015 Preface In this attachment booklet, I will explain a little more about certain topics that I have left out from the main research. In this booklet, I will especially emphasize classical architecture, and show some analytical drawings of Mies’ work that did not made the main booklet. 2 Index 1. Classical architecture………………..………………………………………………………. 4 1.1 . Taxis…………..………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 1.2 . Genera…………..……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.3 . Symmetry…………..…………………………………………………………………………... 12 2. Case studies…………………………..……………………………………………...…………... 16 2.1 . Mies van der Rohe…………………………………………………………………………... 17 2.2 . Palladio………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 2.3 . Ancient Greek temple……………………………………………………………………… 29 3 1. Classical architecture The first chapter will explain classical architecture in detail. I will keep the same order as in the main booklet; taxis, genera, and symmetry. Fig. 1. Overview of classical architecture Source: own image 4 1.1. Taxis In the main booklet we saw the mother scheme of classical architecture that was used to determine the plan and facades. Fig. 2. Mother scheme Source: own image. However, this scheme is only a point of departure. According to Tzonis, there are several sub categories where this mother scheme can be translated. Fig. 3. Deletion of parts Source: own image into into into Fig. 4. Fusion of parts Source: own image 5 Fig. 5. Addition of parts Source: own image into Fig. 6. Substitution of parts Source: own image Into Fig. 7. Translation of the Cesariano mother formula Source: own image 6 1.2. -

Is There a Printer's Copy of Gian Giorgio Trissino's Sophonisba?

Is There a Printer’s Copy of Gian Giorgio Trissino’s Sophonisba? Diego Perotti Abstract This essay examines the manuscript Additional 26873 housed in the British Library. After clarifying its physical features, it then explores various hypotheses as to its origins and its intended use. Finally, the essay collates the codex with Gian Giorgio Trissino’s first edition of the Sophonisba in order to establish the tragedy’s different drafts and the role of the manu- script in the scholarly edition’s plan. The manuscript classified as Additional 26873 (Hereafter La) is housed at the British Library in London and described in the online catalogue as follows: “Ital. Vellum; xvith cent. Injured by fire. Octavo. Giovanni Giorgio Trissino: Sophonisba: a tragedy”. A few details may be added. La is part of a larger collection comprising Additional 26789–26876: eighty-eight items composed in various languages (English, French, Italian, Latin, Portuguese, Spanish), many of which have been damaged to different degrees by fire and damp. The scribe has been identified as Ludovico degli Arrighi (1475–1527), the well-known calligrapher from Vicenza (Veneto, northern-east Italy) who later turned into a typographer, active between his hometown and Rome during the first quarter of the sixteenth century.1 Arrighi’s renowned handwriting, defined as corsivo lodoviciano (Ludovico’s italic), is a calligraphic italic based on the cancelleresca, well distinguished from the latter by the use of upright capitals characterized by long ascend- ers/descenders with curved ends, the lack of ties between characters, the greater space between transcriptional lines, and capital letters slightly 1. -

![List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5354/list-3-2016-accademia-della-crusca-aldine-device-1-bardi-giovanni-1534-1612-465354.webp)

List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]

LIST 3-2016 ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA – ALDINE DEVICE 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]. Ristretto delle grandeze di Roma al tempo della Repub. e de gl’Imperadori. Tratto con breve e distinto modo dal Lipsio e altri autori antichi. Dell’Incruscato Academico della Crusca. Trattato utile e dilettevole a tutti li studiosi delle cose antiche de’ Romani. Posto in luce per Gio. Agnolo Ruffinelli. Roma, Bartolomeo Bonfadino [for Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli], 1600. 8vo (155x98 mm); later cardboards; (16), 124, (2) pp. Lacking the last blank leaf. On the front pastedown and flyleaf engraved bookplates of Francesco Ricciardi de Vernaccia, Baron Landau, and G. Lizzani. On the title-page stamp of the Galletti Library, manuscript ownership’s in- scription (“Fran.co Casti”) at the bottom and manuscript initials “CR” on top. Ruffinelli’s device on the title-page. Some foxing and browning, but a good copy. FIRST AND ONLY EDITION of this guide of ancient Rome, mainly based on Iustus Lispius. The book was edited by Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli and by him dedicated to Agostino Pallavicino. Ruff- inelli, who commissioned his editions to the main Roman typographers of the time, used as device the Aldine anchor and dolphin without the motto (cf. Il libro italiano del Cinquec- ento: produzione e commercio. Catalogo della mostra Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Roma 20 ottobre - 16 dicembre 1989, Rome, 1989, p. 119). Giovanni Maria Bardi, Count of Vernio, here dis- guised under the name of ‘Incruscato’, as he was called in the Accademia della Crusca, was born into a noble and rich family. He undertook the military career, participating to the war of Siena (1553-54), the defense of Malta against the Turks (1565) and the expedition against the Turks in Hun- gary (1594).