Dominant Party Resilience and Valence Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

Doctors' Guide to Working & Living in Singapore

Doctors’ Guide to Working & Living in Singapore www.headmedical.com Working in Singapore Healthcare System Medical Registration Employment Pass Language Requirements Living in Singapore Housing | Education Utilities | Public Transport Climate | Moving Pets Central Provident Fund & Transferring UK Pensions Health Insurance | Contact Us Cost of Living | Link Library Working in Singapore Healthcare System Healthcare in Singapore is mainly under the responsibility of the Singapore Government’s Ministry of Health, and is designed to ensure that everyone has access to different levels of healthcare in a timely and cost-effective manner. Singapore has 8 public hospitals comprising 6 general hospitals, a women’s and children’s hospital, and a psychiatric hospital. General hospitals provide multi-disciplinary inpatient and specialist outpatient services, and 24-hour emergency departments. Six national specialty centres provide cancer, cardiac, eye, skin, neuroscience and dental care. Medical Registration International medical graduates (IMG) are doctors trained overseas. IMGs holding a degree from a university specified in the Second Schedule of the Medical Registration Act (MRA), a registrable postgraduate medical qualification recognised by the SMC or a specialist qualification recognised for specialist accreditation by the Specialists Accreditation Board (SAB), may apply for conditional registration. Conditional registration allows an international medical graduate to work in an SMC-approved healthcare institution, under the supervision of a -

1 Singapore's Dominant Party System

Tan, Kenneth Paul (2017) “Singapore’s Dominant Party System”, in Governing Global-City Singapore: Legacies and Futures after Lee Kuan Yew, Routledge 1 Singapore’s dominant party system On the night of 11 September 2015, pundits, journalists, political bloggers, aca- demics, and others in Singapore’s chattering classes watched in long- drawn amazement as the media reported excitedly on the results of independent Singa- pore’s twelfth parliamentary elections that trickled in until the very early hours of the morning. It became increasingly clear as the night wore on, and any optimism for change wore off, that the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) had swept the votes in something of a landslide victory that would have puzzled even the PAP itself (Zakir, 2015). In the 2015 general elections (GE2015), the incumbent party won 69.9 per cent of the total votes (see Table 1.1). The Workers’ Party (WP), the leading opposition party that had five elected members in the previous parliament, lost their Punggol East seat in 2015 with 48.2 per cent of the votes cast in that single- member constituency (SMC). With 51 per cent of the votes, the WP was able to hold on to Aljunied, a five-member group representation constituency (GRC), by a very slim margin of less than 2 per cent. It was also able to hold on to Hougang SMC with a more convincing win of 57.7 per cent. However, it was undoubtedly a hard defeat for the opposition. The strong performance by the PAP bucked the trend observed since GE2001, when it had won 75.3 per cent of the total votes, the highest percent- age since independence. -

© 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Was Established As an Autonomous Organization in 1968

© 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia, particularly the many-faceted problems of stability and security, economic development, and political and social change. The Institute’s research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS), and the ASEAN Transitional Economies Programme (ATEP). The Institute is governed by a twenty-two-member Board of Trustees comprising nominees from the Singapore Government, the National University of Singapore, the various Chambers of Commerce, and professional and civic organizations. A ten-man Executive Committee oversees day-to-day operations; it is chaired by the Director, the Institute’s chief academic and administrative officer. SOUTHEAST ASIAN AFFAIRS 1998 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Chairperson Chia Siow Yue Editors Derek da Cunha John Funston Associate Editor Tan Kim Keow © 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES © 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore Cataloguing in Publication Data Southeast Asian affairs. 1974– Annual 1. Asia, Southeastern. I. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. DS501 S72A ISSN 0377-5437 ISBN 981-3055-81-2 (softcover) ISBN 981-230-009-0 (hardcover) Published by Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 Internet e-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://merlion.iseas.edu.sg/pub.html All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. -

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore By Netina Tan PhD Candidate Political Science Department University of British Columbia Paper prepared for presentation at CPSA Conference, 28 May 2009 Ottawa, Ontario Work- in-progress, please do not cite without author’s permission. All comments welcomed, please contact author at [email protected] Abstract In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party autocracy is puzzling. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has defied the “third wave”, withstood economic crises and ruled uninterrupted for more than five decades. Will the PAP remain a deviant case and survive the passing of its founding leader, Lee Kuan Yew? Building on an emerging scholarship on electoral authoritarianism and the concept of institutionalization, this paper argues that the resilience of hegemonic party autocracy depends more on institutions than coercion, charisma or ideological commitment. Institutionalized parties in electoral autocracies have a greater chance of survival, just like those in electoral democracies. With an institutionalized leadership succession system to ensure self-renewal and elite cohesion, this paper contends that PAP will continue to rule Singapore in the post-Lee era. 2 “All parties must institutionalize to a certain extent in order to survive” Angelo Panebianco (1988, 54) Introduction In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party regime1 is puzzling (Haas 1999). A small island with less than 4.6 million population, Singapore is the wealthiest non-oil producing country in the world that is not a democracy.2 Despite its affluence and ideal socio- economic prerequisites for democracy, the country has been under the rule of one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP) for the last five decades. -

Jaclyn L. Neo

Jaclyn L. Neo NAVIGATING MINORITY INCLUSION AND PERMANENT DIVISION: MINORITIES AND THE DEPOLITICIZATION OF ETHNIC DIFFERENCE* INTRODUCTION dapting the majority principle in electoral systems for the ac- commodation of political minorities is a crucial endeavour if A one desires to prevent the permanent disenfranchisement of those minorities. Such permanent exclusion undermines the maintenance and consolidation of democracy as there is a risk that this could lead to po- litical upheaval should the political minorities start to see the system as op- pressive and eventually revolt against it. These risks are particularly elevat- ed in the case of majoritarian systems, e.g. those relying on simple plurality where the winner is the candidate supported by only a relative majority, i.e. having the highest number of votes compared to other candidates1. Further- more, such a system, while formally equal, could however be considered substantively unequal since formal equality often fails to recognize the es- pecial vulnerabilities of minority groups and therefore can obscure the need to find solutions to address those vulnerabilities. Intervention in strict majoritarian systems is thus sometimes deemed necessary to preserve effective participation of minorities in political life to ensure a more robust democracy. Such intervention has been considered es- pecially important in societies characterized by cleavages such as race/ethnicity, religion, language, and culture, where there is a need to en- sure that minority groups are not permanently excluded from the political process. This could occur when their voting choices almost never produce the outcomes they desire or when, as candidates, they almost never receive the sufficient threshold of support to win elections. -

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities 469190 789811 9 Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Inter-religious harmony is critical for Singapore’s liveability as a densely populated, multi-cultural city-state. In today’s STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS world where there is increasing polarisation in issues of race and religion, Singapore is a good example of harmonious existence between diverse places of worship and religious practices. This has been achieved through careful planning, governance and multi-stakeholder efforts, and underpinned by principles such as having a culture of integrity and innovating systematically. Through archival research and interviews with urban pioneers and experts, Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities documents the planning and governance of religious harmony in Singapore from pre-independence till the present and Communities Practices Spaces, Religious Harmony in Singapore: day, with a focus on places of worship and religious practices. Religious Harmony “Singapore must treasure the racial and religious harmony that it enjoys…We worked long and hard to arrive here, and we must in Singapore: work even harder to preserve this peace for future generations.” Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore. Spaces, Practices and Communities 9 789811 469190 Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Urban Systems Studies Books Water: From Scarce Resource to National Asset Transport: Overcoming Constraints, Sustaining Mobility Industrial Infrastructure: Growing in Tandem with the Economy Sustainable Environment: -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)“ . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in “sectioning" the material. It is customary tc begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from “ photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

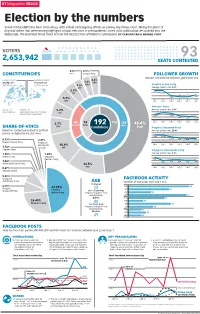

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2 -

Major Vote Swing

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 Major vote swing Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang SMC Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Chua Chu Kang Ang Mo Kio Holland- GRC GRC Pasir Ris- Bukit Punggol GRC Hong Kah Timah North SMC GRC Aljunied Tampines Bishan- GRC GRC Toa Payoh East Coast GRC GRC West Coast Marine GRC Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC MacPherson SMC Mountbatten SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jurong GRC Potong Pasir SMC Chua Chu Kang Registered voters: 119,931; Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Jalan Besar total votes cast: 110,191; rejected votes: 2,949 SMC SMC SMC SMC SMC 76.89% 23.11% (84,731 votes) (25,460 votes) PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY (83 SEATS) WORKERS’ PARTY (6 SEATS) PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih SIX-MEMBER GRC Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif Ang Mo Kio Pasir Ris-Punggol 2011 winner: People’s Action Party (61.20%) Registered voters: 187,771; Registered voters: 187,396; total votes cast: 171,826; rejected votes: 4,887 total votes cast: 171,529; rejected votes: 5,310 East Coast Registered voters: 99,118; 78.63% 21.37% 72.89% 27.11% total votes cast: 90,528; rejected votes: 1,008 (135,115 votes) (36,711 votes) (125,021 votes) (46,508 votes) 60.73% 39.27% (54,981 votes) (35,547 votes) PEOPLE’S THE REFORM PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh J Puthucheary Abu Mohamed PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Darryl David Jesse Loo Ng Chee Meng Arthero Lim ACTION PARTY PARTY Gan -

Achieving-Inclusion

Mee ng the needs of voters with disabili es Copyright © 2016 by Disabled People’s Association, Singapore Published by the Disabled People’s Association, Singapore 1 Jurong West Central 2 #04-01 Jurong Point Shopping Centre Singapore 648886 www.dpa.org.sg All rights reserved. No part nor entirety of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of DPA. 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................ 3 Part I: Electoral System .......................................................... 6 Part II: Barriers to Electoral Participation ............................. 8 Physical barriers ......................................................... 8 Information and communication barriers .................. 9 Systemic barriers ...................................................... 10 Part III: Recommendations .................................................. 11 Physical accessibility ................................................ 11 Information and communication solutions ............. 12 Systemic solutions ................................................... 17 Conclusion ............................................................................ 19 Glossary ................................................................................ 20 References ............................................................................ 24 3 Introduction -

Singapore Local Government System Falls Broadly Within the Allan Model of Virtual Local Government

Virtual Local Government in Practice: * The Case of Town Councils in Singapore Brian Dollery School of Economics University of New England ARMIDALE NSW 2351 Wai Ho Leong Lin Crase Barclays Capital School of Business Level 28, One Raffles Quay La Trobe University South Tower WODONGA VIC 3689 SINGAPORE 048583 Scholars of governance have long sought to develop taxonomic systems of local government that encompass all conceivable institutional arrangements for delivering local goods and services under democratic oversight. A complete typology of this kind would include not only observable real-world municipal models, but also theoretically feasible prototypes not yet in existence. However, despite a growing literature in the area, no universally accepted taxonomy has yet been developed. Notwithstanding this gap in the conceptual literature, existing typological schema have nevertheless proved valuable for both the examination of the characteristics of actual local government systems as well as for comparative studies of different municipal institutional arrangements. For instance, Dollery and Johnson’s (2005) taxonomy of Australian local government has formed the basis of an embryonic literature that seeks to locate the many new municipal * Brian Dollery acknowledges the financial support provided by Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP0770520. The authors would like to thank Mr Chong Weng Yong of the Singapore Housing and Development Board for his kind and valuable assistance in the research for this paper. The views expressed in the paper are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the views of any organization. © Canadian Journal of Regional Science/Revue canadienne des sciences régionales, XXXI: 2 (Summer/Été 2008), 289-304.