The Star's Script: Delon As Director, Producer, and Screenwriter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BORSALINO » 1970, De Jacques Deray, Avec Alain Delon, Jean-Paul 1 Belmondo

« BORSALINO » 1970, de Jacques Deray, avec Alain Delon, Jean-paul 1 Belmondo. Affiche de Ferracci. 60/90 « LA VACHE ET LE PRISONNIER » 1962, de Henri Verneuil, avec Fernandel 2 Affichette de M.Gourdon. 40/70 « DEMAIN EST UN AUTRE JOUR » 1951, de Leonide Moguy, avec Pier Angeli 3 Affichette de A.Ciriello. 40/70 « L’ARDENTE GITANE» 1956, de Nicholas Ray, avec Cornel Wilde, Jane Russel 4 Affiche de Bertrand -Columbia Films- 80/120 «UNE ESPECE DE GARCE » 1960, de Sidney Lumet, avec Sophia Loren, Tab Hunter. Affiche 5 de Roger Soubie 60/90 « DEUX OU TROIS CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D’ELLE» 1967, de Jean Luc Godard, avec Marina Vlady. Affichette de 6 Ferracci 120/160 «SANS PITIE» 1948, de Alberto Lattuada, avec Carla Del Poggio, John Kitzmille 7 Affiche de A.Ciriello - Lux Films- 80/120 « FERNANDEL » 1947, film de A.Toe Dessin de G.Eric 8 Les Films Roger Richebé 80/120 «LE RETOUR DE MONTE-CRISTO» 1946, de Henry Levin, avec Louis Hayward, Barbara Britton 9 Affiche de H.F. -Columbia Films- 140/180 «BOAT PEOPLE » (Passeport pour l’Enfer) 1982, de Ann Hui 10 Affichette de Roland Topor 60/90 «UN HOMME ET UNE FEMME» 1966, de Claude Lelouch, avec Anouk Aimée, Jean-Louis Trintignant 11 Affichette les Films13 80/120 «LE BOSSU DE ROME » 1960, de Carlo Lizzani, avec Gérard Blain, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Anna Maria Ferrero 12 Affiche de Grinsson 60/90 «LES CHEVALIERS TEUTONIQUES » 1961, de Alexandre Ford 13 Affiche de Jean Mascii -Athos Films- 40/70 «A TOUT CASSER» 1968, de John Berry, avec Eddie Constantine, Johnny Halliday, 14 Catherine Allegret. -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

The Queer History of Films and Filming by Justin Bengry

The Queer History of Films and Filming By Justin Bengry It would be hard to exaggerate the sense of repression that many queer men felt in 1950s Britain. Assailed by the press, stalked by the police and dispar- aged by the state, homosexuals experienced almost universal hostility. In 1952, for example, the Sunday Pictorial’s infamous ‘Evil Men’ series ridiculed queer men as “freaks” and “degenerates”; they were, the Pictorial warned, a potent threat to British society.1 In 1953 alone, sensational coverage of charges against Labour M.P. William Field for importuning, author Rupert Croft-Cooke for gross indecency and Shakespearean actor Sir John Gielgud for importuning in a Chelsea lavatory all highlighted the plight of homosexuals. More than any other case, however, the Lord Montagu affair of 1953-4 exposed the dangers posed to homosexuals in Britain. At its conclusion, Lord Montagu, his cousin Michael Pitt-Rivers and Daily Mail diplomatic correspondent Peter Wildeblood were all imprisoned. By 1954, the scandals, trials and social disruption had reached such a frenzy, that amid calls for state intervention, the government relented and called the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution (The Wolfenden Committee) to evaluate the state of criminal law in Britain. That same year, Philip Dosse introduced Films and Filming. Long before homosexual activity between consenting men was decrimina- lised in Britain in 1967, Films and Filming subtly included articles and images, erotically charged commercial advertisements and same-sex contact ads that established its queer leanings. From its initial issues in 1954, the magazine sought Britain’s queer market segment by including articles on the censorship of homosexual themes in film and theatre, profiles and images of sexually ambigu- ous male actors like Dirk Bogarde and Rock Hudson and photo spreads selected specifically for their display of male flesh. -

Le Festival Aura Bien Lieu

SAMEDI 10 OCTOBRE Le journal du Festival « Va voir au 3. Le client de Maurice fait du schproum pour l’addition » Michel Audiard, Le Désordre et la nuit #01 Ça commence ! Ce douzième festival Lumière s’ouvre dans le contexte particulier que traversent Lyon, notre pays et le monde tout entier. C’est dire à quel point il nous tient à cœur que cette manifestation soit riche, diverse et festive. Prudemment festive, bien sûr, dans le respect des gestes auxquels nous nous habituons peu à peu. Mais avec son lot de découvertes, d’enthousiasmes et d’échanges (masqués) avec les artistes qui, comme chaque année, viendront partager leur passion et leurs créations. Plus que jamais le cinéma et l’art en général doivent nous permettre de surmonter les crises, de mieux comprendre le monde et d’aider à le réparer – ce pourrait être le credo de Jean-Pierre et Luc Dardenne, observateurs incisifs de nos sociétés, qui recevront cette JOUR J ! année le Prix Lumière. Dans l’obscurité des salles, le partage d’une émotion, rire, peur ou tristesse, sera la victoire quotidienne de l’imaginaire sur le réel. Cette année, nous serons tous prudents et responsables, mais LE FESTIVAL toujours aussi curieux, attentifs et émerveillés. Soyez les bienvenus ! AURA BIEN LIEU L’équipe du festival ©Jean-Luc Mège CENTENAIRE POLÉMISTE Audiard, ©DR sacré Carrément grand-père Stone Il publie son autobiographie, A la recherche ©DR de la lumière et présente Né un quatre juillet. Dans la famille Audiard, on demande Stéphane, amateur des films de son grand-père. Oliver Stone revient aux racines de son Il raconte le Michel Audiard intime, énorme bosseur et panier percé. -

Les Livres Les Films

LES LIVRES LES FILMS Collections de la MEDIATHEQUE DE SAINT-RAPHAEL DOCUMENTS GENERAUX Le rire : essai sur la signification du comique, Henri Bergson Paris, Presses universitaires de France, coll. Bibliothèque de philosophie contemporaine, 1941 Ce livre comprend trois articles sur le rire ou plutôt sur le rire provoqué par le comique. Ils précisent les procédés de fabrication du comique, ses variations ainsi que l'intention de la société quand elle rit. Histoire des spectacles, Guy Dumur, dir. de publication Paris, Gallimard, coll. Encyclopédie de la Pléiade, 1965 Qu'il soit sacré ou profane, divertissant ou exaltant, que le public y joue un rôle ou, au contraire, se contente d'écouter, de regarder, le spectacle, sous toutes ses formes, fait partie de la vie, au point que nous pourrions difficilement concevoir une société où aucune liturgie, aucune fête, aucun jeu, aucune représentation ne viendrait rompre le rythme du quotidien et peut-être lui donner un sens (ou le dépasser) par le pouvoir en quelque sorte magique de l'illusion... Retrouver les origines et retracer l'histoire, dans les diverses civilisations, de ces manifestations artistiques où le singulier quelquefois se distingue mal du collectif dans la mesure où ils ne peuvent se passer l'un de l'autre ; franchir les distances que créent l'espace et le temps afin de discerner le jeu si compliqué des influences ; découvrir, dans les époques dites de transition, le moment où apparaît une forme nouvelle ; tenter de déterminer les modifications, positives ou négatives, de l'art… Résumé http://www.gallimard.fr Le cinéma comique : Encyclopédie du cinéma, vol. -

Pdf 156.85 KB

Clap de fin pour Mireille Darc Transcription Marie Casadebaig : Mireille Darc s'est éteinte la nuit dernière à Paris. L'actrice avait 79 ans. Nathalie Amar : Une coupe au carré blond platine, des pommettes hautes, elle était l'un des visages familiers du cinéma français des années 60 et 70. Ces derniers mois, elle avait été victime de plusieurs hémorragies cérébrales. Elle laisse, Isabelle Chenu, une filmographie impressionnante. Isabelle Chenu : « La grande sauterelle », c'est le surnom affectueux qui lui était resté après son rôle de femme libérée dans un film de Georges Lautner, metteur en scène avec lequel elle connaîtra ses heures de gloire. Il la fera tourner dans treize de ses films . Elle a fait partie des blondes fatales qui enflammèrent le cinéma français des années 60 aux années 90, et fut une muse pour des réalisateurs comme Édouard Molinaro et Yves Robert, qui lui donnera un de ses rôles les plus populaires dans Le grand blond avec une chaussure noire. C’était aux côtés de Pierre Richard en 1972. Une scène culte, où elle apparaît dans une robe de Guy Laroche échancrée jusqu'aux fesses, entérinera définitivement son statut de sex-symbol. Avec Alain Delon qui sera son compagnon pendant quinze ans elle jouera dans L'homme pressé, Mort d'un pourri ou Les seins de glace. Victime de graves problèmes de santé dans les années 80, Mireille Darc sera opérée à cœur ouvert par le professeur Cabrol. Mais le cinéma et la télévision, où elle jouera dans de multiples feuilletons télévisés très populaires, n'arrêteront jamais de lui faire les yeux doux. -

Gérard DEPARDIEU Benoît POELVOORDE Vincent LACOSTE

JPG FILMS, NO MONEY PRODUCTIONS and NEXUS FACTORY present Gérard Benoît Vincent Céline DEPARDIEU POELVOORDE LACOSTE SALLETTE written and directed by Benoît DELÉPINE & Gustave KERVERN JPG Films, No Money Productions and Nexus Factory present Gérard Benoît Vincent Céline DEPARDIEU POELVOORDE LACOSTE SALLETTE written and directed by Benoît DELÉPINE & Gustave KERVERN 101 min - France/Belgium - 1.85 - 5.1 - 2015 Press materials available for download on www.le-pacte.com INTERNATIONAL PRESS INTERNATIONAL SALES PREMIER - Liz Miller/Sanam Jehanfard LE PACTE [email protected] 5, rue Darcet [email protected] 75017 Paris Berlin: Potsdamer Platz 11, Room 301 Tel: +331 44 69 59 59 Tel: +49 30 2589 4501/02 (10-20 Feb) Synopsis Every year, Bruno, a disheartened cattle breeder, attends the Paris Agricultural Show. This year, his father Jean joins him: he wants to finally win the competition with their bull Nebuchadnezzar and convince Bruno to take over the family farm. Every year, Bruno makes a tour of all the wine stands, without setting foot outside the Show’s premises and without ever finishing his wine trail. This year, his father suggests they finish it together, but a real wine trail, across the French countryside. Accompanied by Mike, a young, quirky taxi driver, they set off in the direction of France’s major wine regions. Together, they are going to discover not only the wine trails, but also the road that leads back to Love. 5 DOES THAT MEAN THAT YOU BRING SOME SUBJECTS TO THE TABLE, BENOÎT? AND GUSTAVE BRINGS OTHERS? GUSTAVE KERVERN: I was born in Mauritius, but we haven’t shot a movie about water-skiing yet. -

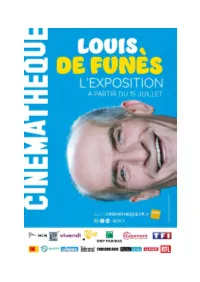

Exposition Louis De Funès

EXPOSITION LOUIS DE FUNÈS 15.07.20 ˃ 31.05.21 Véritable homme-orchestre, de Funès était mime, bruiteur, danseur, chanteur, pianiste, chorégraphe, en somme un créateur, un auteur à part entière. À travers plus de 300 œuvres, peintures, dessins et maquettes, documents, sculptures, costumes et, bien sûr, extraits de films (La Folie des grandeurs, Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob, La Grande Vadrouille, L’Aile ou la cuisse, la série des Gendarme…), l’exposition dévoile ainsi la diversité de son talent comique. EXPOSITION - FILMS - CONFÉRENCES - DISCUSSIONS - LECTURE - VISITES GUIDÉES - CATALOGUE… Alain Kruger, commissaire avec le concours de Thibaut Bruttin Serge Korber, conseiller du commissaire CONTACTS PRESSE LA CINÉMATHÈQUE FRANÇAISE Elodie Dufour [email protected] 01 71 19 33 65 / 06 86 83 65 00 Assistée d’Emmanuel Bolève [email protected] 01 71 19 33 49 2 SOMMAIRE 1- EXPOSITION ET CATALOGUE Du 15 juillet 2020 au 31 mai 2021 p4 Pile électrique et face atomique par Alain Kruger Au fil de l’exposition Catalogue Louis de Funès, à la folie Une coédition Éditions de La Martinière / La Cinémathèque française Visites guidées Les samedis et dimanches 18, 19, 25 et 26 juillet à 11h15 et 14h15. Puis, à partir de septembre : tous les samedis et dimanches à 11h15 Journées d’ateliers pour le jeune public Jeudi 16 juillet de 9h30 à 16h30 / Vendredi 17 juillet de 9h30 à 16h30 2- FILMS + DIALOGUES AVEC DANIÈLE THOMPSON p12 Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob Samedi 12septembre à 15h / Le Corniaud Dimanche 13 septembre à 14h30 3- CONFÉRENCES p13 « -

Sewr.!Njtrn.TC!Epen(,S "!L T,Lt' Point of |

lie will no on ington pay taxes intangibles. wh'ih Hod | >111 in tin- c roll ml for us and tsee f Nothing from nothing leaves nothing*, so the if iliov ciiii'i ilrviiif a wa> l<> lax those natural loss to the Commonwealth will he i. .. m i «.« s into use. anil thou |tn> ilcrfiit salarle ' exactly SEEN ON THE t<> I In- liwlii'm',' REDUCING THE COST SIDE " IH'IMOl'lt.VT. OF LIVING--VIII. TIMES at all. i lot 1KH.1 nothing tcsvillo, V«.. iH'cemlirr -N. UY Taxes will continue to he on Mr. ItoV FHUUIilllC J. HASttiX ,00S- nt 'h' <»HW-e paid IllltpeU. of t i« r'' ». l-'onntlliiu "oil federate Home. ^KuVmVom)liniond, la.. trroiitl-rlnti. niuttrr. an's . ^ H> great estate in Nelson Comity, just as "I'wa.s the lielon> New Year To ih night ¦.alitor of The Times-1 >ispa t oh: WASHINGTON. D. December they have in the past, while under the opera¬ And all thiotmh 111house Sir. Since tlio recent lire sit tIt.> Homo Tor C. 30.. but that style is (In- i'">st expensive ' > r,lr '<« >« S.tqth Truth Is n fiictur in if one I Strict''h,!TV r\ tion of the tax law ami the other Not ti creaturc was stirring Needy i"onfedorato Women, I liave Inul n num¬ Clothing dedicate subject in most clothing. by style Tlmrfc-UlMWUh Puli- segregation ber of calls for so means the fashious tliul coniv :iu«l raplfcWik f« i7 i'h'''il,!hnrl*.. K..ll"' lalitur and Nut oven a mouse. -

La Notte (1961), and L’Eclisse (1962)

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 08, ISSUE 02, 2021 THE ARCHITECTUAL SOUL IN THE BODYOF MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI'S FILMS:SHORTREVIEWONHISTRILOGY: L’AVVENTURA (1960), LA NOTTE (1961), AND L’ECLISSE (1962) GELAREH HAJMOUSA Affiliation Faculty of literature and Philosophy, Sapienza university of Rome, Italy Address: Via dei Volsci, 122, 00185 Roma RM Email: [email protected] Phone: 00393511926186 Abstract In realistic films, the architecture of the cinematic exploitation can be seen. In this regard Antonioni's films has an exceptional place. His films point and desire to create a cinematic experience through the use of filming techniques due to the interplay between architecture and the characters. Antonioni, in his films, uses architecture to depict the mental state of the characters, or perhaps as an arena for closure their logical inconsistencies and contrary qualities.Three films: The adventure (L’Avventura, 1960),The night (La Notte, 1961),and The eclipse(L’Eclisse, 1962) are closely related to the concept and text and are known as the trilogy of the Antonioni. In all of these films, director tries to link the process of emotional development of characters to their position in the film.The emphasis on urban-industrial texture, the unusual story structure, the minimal role of dialogue, and in particular the movements of the camera, which follow the unique methods of cinematic expression, all appear in his work.The Antonionitrilogy are an example of a series of films that are suited to study the purpose of any study on a serious approach to the question of the relationship between two types of substances and artistic creatures. -

Movie Museum MARCH 2013 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum MARCH 2013 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY 2 Hawaii Premieres! 2 Hawaii Premieres! THE INTOUCHABLES SHIRLEY VALENTINE THE INTOUCHABLES MA PETITE MONSIEUR GANGSTER (2011-France) (1989-UK/US) (2011-France) ENTREPRISE aka Les tontons flingueurs in French with English with Pauline Collins, Tom in French with English (1999-France) (1963-France/WGermany/Italy) subtitles & in widescreen Conti, Julia McKenzie, subtitles & in widescreen French w/Eng subtitles, w.s. French w/Eng subtitles, w.s. with François Cluzet, Omar Alison Steadman. Vincent Lindon, Roschdy Zem. Lino Ventura, Bernard Blier. Sy, Anne Le Ny, Audrey 12, 6 & 8pm only with François Cluzet, Omar 12:00 & 8:30pm only 12:00, 6:30 & 8:30pm only Fleurot, Clotilde Mollet. ---------------------------------- Sy, Anne Le Ny, Audrey ---------------------------------- ---------------------------------- Hawaii Premiere! Fleurot, Clotilde Mollet. THE POOL MA PETITE Written and Directed by THE ITALIAN KEY (2007-US) ENTREPRISE Olivier Nakache, Eric Toledano (2011-Finland/US/Italy/UK) Written and Directed by Hindi w/Eng subtitles, w.s. (1999-France) in English in widescreen Olivier Nakache, Eric Toledano with Venkatesh Chavan. French w/Eng subtitles, w.s. 1:30, 3:30, 5:30 with Gwendolyn Anslow. Directed by Chris Smith. Vincent Lindon, Roschdy Zem. & 7:30pm 2 & 4pm only 12, 2, 4, 6 & 8pm 1:30, 3:15, 5 & 6:45pm 7 8 9 10 2, 3:30 & 5pm only 11 Hawaii Premiere! LIFE OF PI Hawaii Premiere! LIFE OF PI St. Patrick's Day LE MAGNIFIQUE MICKYBO AND ME LE CASSE (2012-US/Taiwan) (2012-US/Taiwan) aka The Burglars (1973-France/Italy) (2004-UK) in widescreen French w/Eng subtitles, w.s. -

Gael García Bernal | 3

A film festival for everyone! FESTIVAL 12/20 OCTOBER 2019 – LYON, FRANCE Francis Ford Coppola Lumière Award 2019 © Christian Simonpietri / Getty Images th GUESTS OF HONOR Frances McDormand anniversary10 Daniel Auteuil Bong Joon-ho Donald Sutherland Marco Bellocchio Marina Vlady Gael García Bernal | 3 10th anniversary! 2019. A decade ago, the Lumière festival presented the first Lumière Award to Clint Eastwood in Lyon, the birthplace of the Lumière Cinematograph. As the festival continues to flourish (185,000 moviegoers attended last year), we look forward to commemorating the last ten years. Today, passion for classic cinema is stronger than ever and Lyon never ceases to celebrate the memory of films, movie theaters and audiences. Lumière 2019 will be rich in events. Guests of honor will descend on Lyon from all over the world; Frances McDormand, Daniel Auteuil, Bong Joon-ho, Donald Sutherland, Marco Bellocchio, Marina Vlady and Gael Garcia Bernal will evoke their cinema and their love of films. Retrospectives, tributes, film-concerts, exhibitions, master classes, cinema Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now by Francis Ford Coppola all-nighters, screenings for families and children, a DVD market, a cinema bookstore, the Cinema Fair... a myriad of opportunities to enjoy and cherish heritage works together. THE PROGRAM For this 10th anniversary, the Lumière festival has created Lumière Classics, a section that presents the finest restored films of the year, put forward by archives, RETROSPECTIVES producers, rights holders, distributors, studios and film libraries. The new label focuses on supporting selected French and international films. Francis Ford Coppola: Lumière Award 2019 of crazy freedom. The films broach sex, miscegenation, homosexuality; they feature gangsters and femme A filmmaker of rare genius, fulfilling an extraordinary fatales, embodied by Mae West, Joan Crawford and Also new, the International Classic Film Market Village will hold a DVD Publishers’ destiny, auteur of some of the greatest successes and th Barbara Stanwyck… Directors like William A.