I: the Townfields of Lancashire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrew Egan Tells Catena How an Idea Was Turned Into Action at Harrow Circle

CATENA No.1092 - OCTOBER 2020 The Magazine of the Catenian Association - £2 OCTOBER 2020 • CATENA 1 www.thecatenians.com Catena Advertising Rates CONTENTS DISPLAY Whole page (210mm x 297mm deep) £536 Half page (190mm x 135mm deep) £268 Quarter page (94mm x 135mm deep) £136 Eighth page (94mm x 66mm deep) £75 INSERTS Usually £51-67 per 1000 depending on size & weight CLASSIFIEDS Start from £50 CIRCLES Advertising commemorative meetings, dinners or special functions: Whole page - £158; half page - £84 All advert prices plus VAT 07 09 Copy date: 1st of month prior to publication WEB ADVERTISING Banner advertising: £51 per month + VAT Special packages available for combined display and web advertising. All communications relating to advertisements should be directed to: Advertising Manager Beck House, 77a King Street, Knutsford, Cheshire WA16 6DX Mob: 07590 851 183 Email: [email protected] Catena Advertising Terms and Conditions Catena is published by Catenian Publications Ltd for the Catenian Association Ltd. Advertisements and inserts are accepted subject to the current Terms and Conditions and the approval of the Editor acting on behalf of the publisher. The publisher’s decision is final. The publisher accepts advertisements and inserts on the condition that: 1. The advertiser warrants that such material does not contravene the provisions of the Trade Descriptions Act, and complies with the British Code of Advertising Practice 36 and the Distance Selling Directive. 2. The advertiser agrees to indemnify the publisher regarding claims arising due to breach(es) of condition 1 above, and from claims arising out of any libellous or malicious matter; untrue statement; or infringement of copyright, patent or design relating to any advertisement or insert published. -

This Work Is Protected by Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Rights

This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. Vernacular Writings in the Medieva} Libraries of Great Britain I Glenise Scott, Ph.0. thesis, Keel e, 1 980. ABSTRACT The thesis comprises four volumes: an introductory discussion; two volumes containing lists of religious and other institutions with information on the works in the vernacular languages which they are known to have owned; and a volume of indices and bibliographies. The information is obtained from the surviving books of the medieval period, here taken as extending to 1540, which are known to have belonged to the religious and other houses, and from their medieval catalogues, book-lists and other documents. With the help of the indices, one may find the information relevant to a particular house, to an Anglo-Saxon, French or English work, or to a given manuscript. The introduction makes some general’observations concerning the libraries and books of medieval institutions, lists the medieval catalogues and book-lists chronologically, and considers the various kinds of vernacular writings, with particular reference to their production and ownership by the religious houses. Finally, some areas for further research are indicated. -

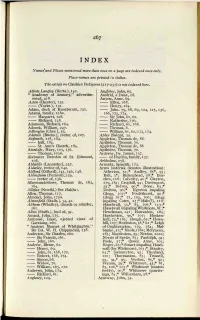

Kamesand Places Mentioned More Tlian Once on a Page Are Indexed Once Only

INDEX Kamesand Places mentioned more tlian once on a page are indexed once only. Place-names are printed in italics. The article on Cheshire Pedigrees (217-237) is not indexed here. Abbots Langley (Herts.), 142. Anglizer, John, 65. " Academy of Armory," advertise Ansfrid, a Dane, 28. ment, 218. Anyon, Anne, 69. Acton (Chester), 132. Ellen, 168. (Yorks.), 132. Henry, 164. Adam, clerk of Knoctorum, 121. John. 59, 68, 69, 124, 125, 131, Adams, family, I28n. 166', 172, 174. Margaret, 128. Sir John, 61,62. Richard, 128. Katherine, 170. Adamson, Richard, 164. Richard, 61, 168. Adcock, William, 247. Thomas, 6. Adlington (dies ), 53. William, 61,62, i 73,174. Adstock (Bucks.), rector of, 107. Apley (Salop), 34. Aigburth, 178, 184. Appleton, Thomas de, 88. hall, 184. Apthider, Thomas, 70. St. Ann's Church, 184. Appleton, Thomas de, 88 Ainsdale, Mary, 103, 156. Apthider, Thomas, 70. Thomas, 10311. Ardcrne, Dr. James, r37. Alabaster Reredos of St. Edmund, of Harden, family, 137. 208. Arkholme, 258. Aldcliffe (Lancaster), 257. Armada, Spanish, 173. Alderley, rector of, 142. Arms (asterisk denotes illustration): Aldfprd (Odford), 145,146, 148. Atherton, 52;* Audley, 8=;*, 93; Aldingham (Furness),239. Ball, 3*; Birkcnhead, 58;* Bur- rector of, r36. ches, 128; Calveley, 42 ;* Clayton, Alkemundeslowe, Thomas de, 163, 179, r84; Crophill, 94; Davenport, 164. 55;* Delves, 90;* Done, 63;* Allefax (Newfld.) See Haliia:. Dutton, 90;* Egerton impaling Alien, Thomas, 117. Glegg, 107;* Fouleshurst, 90;* Almond, John, i75«. Glegg 16;* 71, 105, ro6; Glegg Alstonfield (Staffs.), 34, 41. inpaling Cotes, 25;*Hale(?), irS; Altham (Whalley), church or minster, Haselwali, 33,* 83, ro6,* 113;* 26r. -

The Black Death of 1348 and 1349

THE BLACK DEA TH Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com LONDON : GBOllGE BELL AND SONI POaTOGAL ST. LINCOLN'S INN, W.C. CAMBaIDGE : DEIGHTON, BELL & CO. NEW YOllK: THE IIACIULLAN CO. BOMBAY: A. H. WHULll & CO. Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com THE BLACK DEA TH OF I 348 AND I 349 BY FRANCIS AIDAN GASQUET, D.D. ABBOT P&UJD&MT OP TH& SNGLJSH B&NIU>JCTJNU SECOND EDITION I LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS 1908 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com~ ' ,.J rt~, . ,_.,-- I f L I B 2 :\ t-r l · --- --- ·- __.. .. ,,,.- --- CHISWICX PRESS: CHAI.LBS WHITTINGHAII AND CO, TOOXS couaT, CBANCEI.Y LANE, LONDON, Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREF ACE TO THE SECOND EDITION HIS essay, published in 1893, has long Tbeen out of print, and second-hand copies are difficult to procure, as they very rarely find their way into booksellers' catalogues. For this reason it has been thought well to reprint this account of the greatest plague that has probably ever devastated the world in historic times. Al though the subject is necessarily of a doleful and melancholy character, it is of importance in the . world's history, both as the account of a universal catastrophe and in its far-reaching effects. Since the original. publication of Tl,e Great Pestilence additional interest in the subject of bubonic plague has been aroused by the alarming mortality recently caused by it in India, and by the threatened outbreaks in various parts of Europe, where, however, the watchful care of the sanitary authorities has so far enabled them to deal with the sporadic cases which have appeared during the past few years, and to prevent the spread of the terrible scourge. -

Issue 393 October 2020 St Thomas' Parish Church Vicar St Annes-On-The-Sea Rev Chris Scargill MA Bth [email protected] Tel: 725551

The Parish Magazine of St Thomas' Church, St Annes-on-the-Sea £1 Issue 393 October 2020 St Thomas' Parish Church Vicar St Annes-on-the-Sea Rev Chris Scargill MA Bth [email protected] tel: 725551 Licensed Lay Ministers Miss Elizabeth O'Connor Mr Peter Watson tel: 729725 Mrs Deborah Wood tel: 726536 Churchwardens Mrs Kath Asquith tel: 367768 Mrs Joy Swarbrick tel: 723966 telephone: 01253 727226 website: www.stthomas.uk.net Organist and Musical Director email: [email protected] Mrs Mandy Palmer t el: 711794 Pastoral Letter Dear Friends, As we move into October, the nights are beginning to draw in and the end of 2020 seems to be in sight. Harvest Festival is upon us and it won't be long until All Saints, All Souls and Remembrance Sunday. Yet the Coronavirus pandemic, which many of us thought might be over by the summer, is still casting its shadow over us and will probably continue to do so past Christmas and New Year. Indeed, I found myself thinking today that next year's Lent course will have to have a rather different format than before. However, it is not my intention to make us all feel even more depressed. Rather than simply thinking about how frustrating the last seven months or so have been or worrying about the next six or seven, perhaps we should think about what this time has taught us. After all Saint Paul assures us that God works in all things for good; so what are the positives we can draw out of this time? As I suggested in last month's magazine, we have all had more time to reflect upon the world around us, to listen to the birds, to watch the flowers − or the weeds − grow, to walk by the sea. -

Durham Priory

Durham Priory – Prior of Lytham’s Accounts (performances are at Durham except where marked L; L+D indicates accounts that include performances at both Lytham and Durham; accounts probably relating to Lancashire performances are in brown – but see End Note 1456-7 for doubtful cases) Introduction 1342-1534, but there is no relevant material before 1346. One membrane, length 310-802 mm., width 203-335 mm. Single-column with undivided expenses. The first relevant account has expenses written as a continuous paragraph, but thereafter each item has a separate line. The usual terminal date is the Monday after Ascension, except for the period 1393-5, when it is Pentecost (on 1394-5, see Textual Note). In 1456-7 the account runs from St. Lawrence (10th August) to the Monday after Ascension; the account for the earlier part of the year may never have been written, since the eccentric opening date was caused by the death of the previous Prior – see Textual Note. Lytham Priory, on the north bank of the River Ribble, was founded between 1189 and 1194 as a result of a gift from Richard Fitz Roger, a local magnate who was inspired by gratitude to St. Cuthbert for miraculous cures of himself and his infant son.1 It was relatively prosperous, but for much of the time from the early fifteenth century until the dissolution its prior was on bad terms with many of the local landowners. The exception was during the priorate of William Partrike (1431-1446), a rather acquisitive monk who took the side of the local magnates against the mother house and tried unsuccessfully to detach Lytham from its dependence on Durham.2 In view of this, the large number of payments to minstrels at Lytham seems surprising, as does their absence from precisely the period of Partrike’s priorate, despite the survival of an almost complete run of accounts for that period. -

Remains, Historical & Literary

GENEALOGY COLLECTION Cj^ftljnm ^Ofiftg, ESTABLISHED MDCCCXLIII. FOR THE PUBLICATION OF HISTORICAL AND LITERARY REMAINS CONNECTED WITH THE PALATINE COUNTIES OF LANCASTER AND CHESTEE. patrons. The Right Hon. and Most Rev. The ARCHBISHOP of CANTERURY. His Grace The DUKE of DEVONSHIRE, K.G.' The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHESTER. The Most Noble The MARQUIS of WESTMINSTER, The Rf. Hon. LORD DELAMERE. K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD DE TABLEY. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of DERBY, K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD SKELMERSDALE. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of CRAWFORD AND The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY of Alderlev. BALCARRES. SIR PHILIP DE M ALPAS GREY EGERTON, The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY, M.P. Bart, M.P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHICHESTER. GEORGE CORNWALL LEGH, Esq , M,P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of MANCHESTER JOHN WILSON PATTEN, Esq., MP. MISS ATHERTON, Kersall Cell. OTounctl. James Crossley, Esq., F.S.A., President. Rev. F. R. Raines, M.A., F.S.A., Hon. Canon of ^Manchester, Vice-President. William Beamont. Thomas Heywood, F.S.A. The Very Rev. George Hull Bowers, D.D., Dean of W. A. Hulton. Manchester. Rev. John Howard Marsden, B.D., Canon of Man- Rev. John Booker, M.A., F.S.A. Chester, Disney Professor of Classical Antiquities, Rev. Thomas Corser, M.A., F.S.A. Cambridge. John Hakland, F.S.A. Rev. James Raine, M.A. Edward Hawkins, F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S. Arthur H. Heywood, Treasurer. William Langton, Hon. Secretary. EULES OF THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. 1. -

Radiocarbon Dates

PINK?book covers (18mm) v2:Layout 1 13-03-12 11:01 AM Page 1 RADIOCARBON DATES RADIOCARBON DATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 882 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1988 and 1993 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference and from samples funded by English Heritage analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy of the between 1988 and 1993 dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are published, although, when some of these measurements were produced, high-precision calibration was not possible for much of the radiocarbon timescale. At this time, there was also only a limited range of statistical techniques available for the analysis of radiocarbon dates. Methodological developments since these measurements were made may allow revised archaeological interpretations to be constructed on the basis of these dates, and so the purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Alex Christopher Gordon Bayliss, GerryCook, Bronk Ramsey, McCormac, Walker Robert and Otlet, Jill Front cover: -

The Building Accounts of Kirby Muxloe Castle, 1480-1484

THE BUILDING ACCOUNTS OE KIEBT! MUXLOE CASTLE. 193 THE BUILDING ACCOUNTS OF KIRBY MUXLOE CASTLE, 1480-1484. EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES, BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A., F.S.A. INTRODUCTION. A brief description of the MS. volume of accounts, of which a summary edition follows here, has been given already in our Transactions by Mr. T. H. Fosbrooke, together with a photo graphic reproduction of two of its leaves.3 It will be remembered that it is the record of the weekly expenses disbursed in connexion with the rebuilding or, as the steward who cast up the accounts more accurately calls it, the repair of the castle of Kirby Muxloe. Since the discovery of the MS., it has been examined by Mr. C. R. Peers, Professor Lethaby and other architectural scholars ; but it has remained untranscribed and unedited. Early in 1917 the present writer was enabled, through the good offices of his friend Mr. Fosbrooke, to undertake the task ; and the results are now presented to members of our Society. The work begun in October, 1480, by order of William, lord Hastings, was the transformation of the manor-house or small castle which already existed at Kirby into a fortified dwelling of considerable size and importance. We know nothing ot the earlier building apart from the few indications contained in the accounts, which show that it stood on part of the present site and that its hall was retained when the new inner court was made. Lord Hastings' work included the formation of this inner court, the castle proper, which he surrounded with a moat and a brick wall. -

Monasteries As Financial Patrons and Promoters of Local Performance in Late Medieval and Early Tudor England

Quidditas Volume 26 Volume 26-27, 2005-2006 Article 8 2005 Monasteries as Financial Patrons and Promoters of Local Performance in Late Medieval and Early Tudor England Christine Sustek Williams Charleston Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Christine Sustek (2005) "Monasteries as Financial Patrons and Promoters of Local Performance in Late Medieval and Early Tudor England," Quidditas: Vol. 26 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol26/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 26 & 27 (2005-2006) 51 Monasteries as Financial Patrons and Promoters of Local Performance in Late Medieval and Early Tudor England Christine Sustek Williams Charleston Southern University The elaborate cycle plays produced in the larger, wealthy municipalities of York, Chester, Wakefield and Coventry receive the lion’s share of attention among scholars of medieval theatre. Until recently, performance activities in smaller communities have received little or no attention, except perhaps as something of antiquarian interest. And one area of theatre history that has been largely overlooked is the involvement of monasteries in local performance activities. Yet the precious few, fragmentary, monastic records that survived the dissolutions of the monasteries under Henry VIII and Edward VI, suggest that several monasteries gave active financial support to local theatre in England before and during the early Tudor period. -

The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales –

Cambridge University Press 0521802717 - The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales, 1216-1377 Edited by Professor David M. Smith and Vera C. M. London Frontmatter More information The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales – This book is the long-awaited continuation of The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales –, edited by David Knowles, C. N. L. Brooke, and Vera London, which itself is now reissued with substantial addenda by Professor Brooke. This present volume continues the lists from to . In this period further record sources have been provided by episcopal registers, governmental enrol- ments, court records, and so on. Full references are given for establishing the dates and outline of the career of each abbot or prior, abbess or prioress, when known, although the information varies considerably from the richly documented lists of the great Benedictine houses to the small cells where perhaps only a single name or date may be recorded in a chance archival survival. The lists are arranged by order: the Benedictine houses (independent, depen- dencies, and alien priories); the Cluniacs; the Grandmontines; the Cistercians; the Carthusians; the Augustinian canons; the Premonstratensians; the Gilbertine order; the Trinitarian houses; the Bonhommes; and the nuns. An introduction dis- cusses the nature, use, and history of the lists and examines critically the sources on which they are based. . is Professor and Director of the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, University of York. . is co-editor, with David Knowles and Christopher Brooke, of The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales – (). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521802717 - The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales, 1216-1377 Edited by Professor David M. -

Archaeological Evaluation Report Lytham Hall, Lytham, Lancashire

Archaeological Evaluation Report Lytham Hall, Lytham, Lancashi re Client: Heritage Trust for the North West Technical Report: Rachael Reader Report No: 2016/3 © Salford Archaeology: Evaluation Report: Lytham Hall, Lytham, Lancashire (SA/EVAL/2016/3) Site Location: Lytham Hall, Lytham, Lancashire, FY8 4JX NGR: SD 35676 27969 Internal Ref: SA/EVAL/2016/3 Proposal: Archaeological Evaluation Planning Ref: N/A Prepared for: Simon Thorpe, Lytham Hall Project Manager (Heritage Trust for the North West) Document Title: Archaeological Evaluation: Lytham Hall, Lancashire Document Type: Archaeological Evaluation Report Version: 1.0 Author: Rachael Reader BA Hons, MA, PhD, ACIfA Position: Supervising Archaeologist Date: February 2016 Approved by: Adam J Thompson BA Hons, MA, MIFA Position: Director of Archaeology Date: February 2016 Signed:………………….. Copyright: Copyright for this document remains with Salford Archaeology, University of Salford. Contact: Salford Archaeology, University of Salford, Peel Building, University of Salford, Salford Telephone: 0161 295 2545 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: This document has been prepared by the Centre for Applied Archaeology, University of Salford for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be used or relied upon for any other project without an independent check being undertaken to assess its suitability and the prior written consent and authority obtained from the Centre for Applied Archaeology. The University of Salford accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than those for which it was commissioned. Other persons/parties using or relying on this document for other such purposes agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm their agreement to indemnify the University of Salford for all loss or damage resulting therefrom.