This Work Is Protected by Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrew Egan Tells Catena How an Idea Was Turned Into Action at Harrow Circle

CATENA No.1092 - OCTOBER 2020 The Magazine of the Catenian Association - £2 OCTOBER 2020 • CATENA 1 www.thecatenians.com Catena Advertising Rates CONTENTS DISPLAY Whole page (210mm x 297mm deep) £536 Half page (190mm x 135mm deep) £268 Quarter page (94mm x 135mm deep) £136 Eighth page (94mm x 66mm deep) £75 INSERTS Usually £51-67 per 1000 depending on size & weight CLASSIFIEDS Start from £50 CIRCLES Advertising commemorative meetings, dinners or special functions: Whole page - £158; half page - £84 All advert prices plus VAT 07 09 Copy date: 1st of month prior to publication WEB ADVERTISING Banner advertising: £51 per month + VAT Special packages available for combined display and web advertising. All communications relating to advertisements should be directed to: Advertising Manager Beck House, 77a King Street, Knutsford, Cheshire WA16 6DX Mob: 07590 851 183 Email: [email protected] Catena Advertising Terms and Conditions Catena is published by Catenian Publications Ltd for the Catenian Association Ltd. Advertisements and inserts are accepted subject to the current Terms and Conditions and the approval of the Editor acting on behalf of the publisher. The publisher’s decision is final. The publisher accepts advertisements and inserts on the condition that: 1. The advertiser warrants that such material does not contravene the provisions of the Trade Descriptions Act, and complies with the British Code of Advertising Practice 36 and the Distance Selling Directive. 2. The advertiser agrees to indemnify the publisher regarding claims arising due to breach(es) of condition 1 above, and from claims arising out of any libellous or malicious matter; untrue statement; or infringement of copyright, patent or design relating to any advertisement or insert published. -

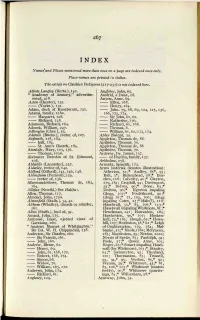

Kamesand Places Mentioned More Tlian Once on a Page Are Indexed Once Only

INDEX Kamesand Places mentioned more tlian once on a page are indexed once only. Place-names are printed in italics. The article on Cheshire Pedigrees (217-237) is not indexed here. Abbots Langley (Herts.), 142. Anglizer, John, 65. " Academy of Armory," advertise Ansfrid, a Dane, 28. ment, 218. Anyon, Anne, 69. Acton (Chester), 132. Ellen, 168. (Yorks.), 132. Henry, 164. Adam, clerk of Knoctorum, 121. John. 59, 68, 69, 124, 125, 131, Adams, family, I28n. 166', 172, 174. Margaret, 128. Sir John, 61,62. Richard, 128. Katherine, 170. Adamson, Richard, 164. Richard, 61, 168. Adcock, William, 247. Thomas, 6. Adlington (dies ), 53. William, 61,62, i 73,174. Adstock (Bucks.), rector of, 107. Apley (Salop), 34. Aigburth, 178, 184. Appleton, Thomas de, 88. hall, 184. Apthider, Thomas, 70. St. Ann's Church, 184. Appleton, Thomas de, 88 Ainsdale, Mary, 103, 156. Apthider, Thomas, 70. Thomas, 10311. Ardcrne, Dr. James, r37. Alabaster Reredos of St. Edmund, of Harden, family, 137. 208. Arkholme, 258. Aldcliffe (Lancaster), 257. Armada, Spanish, 173. Alderley, rector of, 142. Arms (asterisk denotes illustration): Aldfprd (Odford), 145,146, 148. Atherton, 52;* Audley, 8=;*, 93; Aldingham (Furness),239. Ball, 3*; Birkcnhead, 58;* Bur- rector of, r36. ches, 128; Calveley, 42 ;* Clayton, Alkemundeslowe, Thomas de, 163, 179, r84; Crophill, 94; Davenport, 164. 55;* Delves, 90;* Done, 63;* Allefax (Newfld.) See Haliia:. Dutton, 90;* Egerton impaling Alien, Thomas, 117. Glegg, 107;* Fouleshurst, 90;* Almond, John, i75«. Glegg 16;* 71, 105, ro6; Glegg Alstonfield (Staffs.), 34, 41. inpaling Cotes, 25;*Hale(?), irS; Altham (Whalley), church or minster, Haselwali, 33,* 83, ro6,* 113;* 26r. -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

The Black Death of 1348 and 1349

THE BLACK DEA TH Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com LONDON : GBOllGE BELL AND SONI POaTOGAL ST. LINCOLN'S INN, W.C. CAMBaIDGE : DEIGHTON, BELL & CO. NEW YOllK: THE IIACIULLAN CO. BOMBAY: A. H. WHULll & CO. Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com THE BLACK DEA TH OF I 348 AND I 349 BY FRANCIS AIDAN GASQUET, D.D. ABBOT P&UJD&MT OP TH& SNGLJSH B&NIU>JCTJNU SECOND EDITION I LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS 1908 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com~ ' ,.J rt~, . ,_.,-- I f L I B 2 :\ t-r l · --- --- ·- __.. .. ,,,.- --- CHISWICX PRESS: CHAI.LBS WHITTINGHAII AND CO, TOOXS couaT, CBANCEI.Y LANE, LONDON, Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREF ACE TO THE SECOND EDITION HIS essay, published in 1893, has long Tbeen out of print, and second-hand copies are difficult to procure, as they very rarely find their way into booksellers' catalogues. For this reason it has been thought well to reprint this account of the greatest plague that has probably ever devastated the world in historic times. Al though the subject is necessarily of a doleful and melancholy character, it is of importance in the . world's history, both as the account of a universal catastrophe and in its far-reaching effects. Since the original. publication of Tl,e Great Pestilence additional interest in the subject of bubonic plague has been aroused by the alarming mortality recently caused by it in India, and by the threatened outbreaks in various parts of Europe, where, however, the watchful care of the sanitary authorities has so far enabled them to deal with the sporadic cases which have appeared during the past few years, and to prevent the spread of the terrible scourge. -

16 July 2008 Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, Marsha and I

16 July 2008 Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, Marsha and I arrived in Shannon and then were driven to the Bishop’s House in the Diocese of Tuam, where we stayed with Bishop Richard Henderson, his wife Anita, and their ‘children.’ As previously posted, a great time was had by all. We then drove back to the Shannon airport with Bishop Richard for our journey to our next leg of this remarkable trip. We arrived at the airport where we were told that the radar at Dublin had ‘crashed’ several days prior, and that flights in and out were being delayed/canceled. Our flight, presently, was on time. We held our breath to see if we would get out. Our flight was, for the most part, on time, and we arrived in Dublin with plenty of time to spare. As we walked through the airport we noticed that most of the outgoing flights were delayed by several hours. Our flight to Heathrow was posted as ‘on time.’ It was only at boarding time that it was rescheduled for about an hour later. Once aboard, the pilot announced that if we didn’t all get situated in our seats immediately we would miss our ‘window of opportunity’ and would possibly not get out that evening. I have never seen so many people sit down in an airplane so quickly as I did that night. We departed about an hour late, but eventually arrived in Heathrow to pick up our luggage. (As one might imagine, two of our bags were the very last to come off the belt.) About a decade ago a young priest came to stay with us. -

Scribal Authorship and the Writing of History in Medieval England / Matthew Fisher

Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture Ethan Knapp, Series Editor Scribal Authorship and the Writing of History in SMedieval England MATTHEW FISHER The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fisher, Matthew, 1975– Scribal authorship and the writing of history in medieval England / Matthew Fisher. p. cm. — (Interventions : new studies in medieval culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1198-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1198-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9299-0 (cd) 1. Authorship—History—To 1500. 2. Scribes—England—History—To 1500. 3. Historiogra- phy—England. 4. Manuscripts, Medieval—England. I. Title. II. Series: Interventions : new studies in medieval culture. PN144.F57 2012 820.9'001—dc23 2012011441 Cover design by Jerry Dorris at Authorsupport.com Typesetting by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro and ITC Cerigo Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS List of Abbreviations vi List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION 1 ONE The Medieval Scribe 14 TWO Authority, Quotation, and English Historiography 59 THREE History’s Scribes—The Harley Scribe 100 FOUR The Auchinleck Manuscript and the Writing of History 146 EPILOGUE 188 Bibliography 193 Manuscript Index 213 General Index 215 ABBrEviationS ANTS Anglo-Norman Text Society BL British Library CUL Cambridge University Library EETS Early English Text Society (OS, Original Series, ES, Extra Series, SS Supplementary Series) LALME A Linguistic Atlas of Late Medieval English, ed. -

Issue 393 October 2020 St Thomas' Parish Church Vicar St Annes-On-The-Sea Rev Chris Scargill MA Bth [email protected] Tel: 725551

The Parish Magazine of St Thomas' Church, St Annes-on-the-Sea £1 Issue 393 October 2020 St Thomas' Parish Church Vicar St Annes-on-the-Sea Rev Chris Scargill MA Bth [email protected] tel: 725551 Licensed Lay Ministers Miss Elizabeth O'Connor Mr Peter Watson tel: 729725 Mrs Deborah Wood tel: 726536 Churchwardens Mrs Kath Asquith tel: 367768 Mrs Joy Swarbrick tel: 723966 telephone: 01253 727226 website: www.stthomas.uk.net Organist and Musical Director email: [email protected] Mrs Mandy Palmer t el: 711794 Pastoral Letter Dear Friends, As we move into October, the nights are beginning to draw in and the end of 2020 seems to be in sight. Harvest Festival is upon us and it won't be long until All Saints, All Souls and Remembrance Sunday. Yet the Coronavirus pandemic, which many of us thought might be over by the summer, is still casting its shadow over us and will probably continue to do so past Christmas and New Year. Indeed, I found myself thinking today that next year's Lent course will have to have a rather different format than before. However, it is not my intention to make us all feel even more depressed. Rather than simply thinking about how frustrating the last seven months or so have been or worrying about the next six or seven, perhaps we should think about what this time has taught us. After all Saint Paul assures us that God works in all things for good; so what are the positives we can draw out of this time? As I suggested in last month's magazine, we have all had more time to reflect upon the world around us, to listen to the birds, to watch the flowers − or the weeds − grow, to walk by the sea. -

Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Christ Church 3 Senior Members’ Activities and Publications 81 The House in 2019 13 The Archives 18 News from Old Members 101 The Cathedral 19 Cathedral Music 22 Deceased Members 109 The College Chaplain 25 The College Choir 27 Final Honour Schools 111 The Development & Alumni Office 28 Graduate Degrees 115 The Library 37 The Picture Gallery 41 Award of University Prizes 117 The Steward’s Dept. 47 The Treasury 49 Information about Gaudies 118 Tutor for Admissions 52 Junior Common Room 55 Christ Church Other Information Arts Week 58 Other opportunities to stay The Christopher Tower at Christ Church 120 Poetry Prize 59 Conferences at Christ Sports Clubs 61 Church 121 Publications 122 Christ Church Chemists Cathedral Choir CDs 123 Affinity Group 62 Not Going Gently 63 Acknowledgements 123 Christ Church Pancake Races 66 Mr Edward Burn 67 Sir Michael Howard 70 Lt. Col. David Edwards 73 James (Jim) Forrest 78 William (Bill) Gray 80 1 2 CHRIST CHURCH Visitor HM THE QUEEN Dean Percy, The Very Revd Martyn William, BA Brist, MEd Sheff, PhD KCL. Canons Gorick, The Venerable Martin Charles William, MA (Cambridge), MA (Oxford) Archdeacon of Oxford Biggar, The Revd Professor Nigel John, MA PhD (Chicago), MA (Oxford), Master of Christian Studies (Regent Coll Vancouver) Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology Foot, The Revd Professor Sarah Rosamund Irvine, MA PhD (Cambridge) Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History Ward, The Revd Graham, MA PhD (Cambridge) Regius Professor of Divinity Newey, The Revd Edmund James, MA (Cambridge), -

Durham Priory

Durham Priory – Prior of Lytham’s Accounts (performances are at Durham except where marked L; L+D indicates accounts that include performances at both Lytham and Durham; accounts probably relating to Lancashire performances are in brown – but see End Note 1456-7 for doubtful cases) Introduction 1342-1534, but there is no relevant material before 1346. One membrane, length 310-802 mm., width 203-335 mm. Single-column with undivided expenses. The first relevant account has expenses written as a continuous paragraph, but thereafter each item has a separate line. The usual terminal date is the Monday after Ascension, except for the period 1393-5, when it is Pentecost (on 1394-5, see Textual Note). In 1456-7 the account runs from St. Lawrence (10th August) to the Monday after Ascension; the account for the earlier part of the year may never have been written, since the eccentric opening date was caused by the death of the previous Prior – see Textual Note. Lytham Priory, on the north bank of the River Ribble, was founded between 1189 and 1194 as a result of a gift from Richard Fitz Roger, a local magnate who was inspired by gratitude to St. Cuthbert for miraculous cures of himself and his infant son.1 It was relatively prosperous, but for much of the time from the early fifteenth century until the dissolution its prior was on bad terms with many of the local landowners. The exception was during the priorate of William Partrike (1431-1446), a rather acquisitive monk who took the side of the local magnates against the mother house and tried unsuccessfully to detach Lytham from its dependence on Durham.2 In view of this, the large number of payments to minstrels at Lytham seems surprising, as does their absence from precisely the period of Partrike’s priorate, despite the survival of an almost complete run of accounts for that period. -

Memorials of Old Staffordshire, Beresford, W

M emorials o f the C ounties of E ngland General Editor: R e v . P. H. D i t c h f i e l d , M.A., F.S.A., F.R.S.L., F.R.Hist.S. M em orials of O ld S taffordshire B e r e s f o r d D a l e . M em orials o f O ld Staffordshire EDITED BY REV. W. BERESFORD, R.D. AU THOft OF A History of the Diocese of Lichfield A History of the Manor of Beresford, &c. , E d i t o r o f North's .Church Bells of England, &■V. One of the Editorial Committee of the William Salt Archaeological Society, &c. Y v, * W ith many Illustrations LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & SONS, 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE, W. 1909 [All Rights Reserved] T O T H E RIGHT REVEREND THE HONOURABLE AUGUSTUS LEGGE, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF LICHFIELD THESE MEMORIALS OF HIS NATIVE COUNTY ARE BY PERMISSION DEDICATED PREFACE H ILST not professing to be a complete survey of Staffordshire this volume, we hope, will W afford Memorials both of some interesting people and of some venerable and distinctive institutions; and as most of its contributors are either genealogically linked with those persons or are officially connected with the institutions, the book ought to give forth some gleams of light which have not previously been made public. Staffordshire is supposed to have but little actual history. It has even been called the playground of great people who lived elsewhere. But this reproach will not bear investigation. -

Autumn Leaves

Autumn Leaves EBC e-catalogue 31 2020 George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK 01225 466000 [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com 1. AESOP. Aesop's Fables. With Instructive Morals and Reflections, Abstracted from all Party Considerations, Adapted To All Capacities; And designed to promote Religion, Morality, and Universal Benevolence. Containing Two Hundred and Forty Fables, with a Cut Engrav'd on Copper to each Fable. And the Life of Aesop prefixed, by Mr. Richardson. Engraved title-page and 25 plates each with multiple images. 8vo. [173 x 101 x 20 mm]. xxxiii, [iii], 192pp. Bound in contemporary mottled calf, the spine divided into six panels with raised bands and gilt compartments, lettered in the second on a red goatskin label, the others tooled in gilt with a repeated circular tool, the edges of the boards tooled with a gilt roll, plain endleaves and edges. (Rubbed, upper headcap chipped). [ebc6890] London: printed for J. Rivington, R. Baldwin, J. Hawes, W. Clarke, R. Collins, T. Caslon, S. Crowder, T. Longman, B. Law, R. Withy, J. Dodsley, G. Keith, G. Robinson, J. Roberts, & T. Cadell, [1760?]. £1000 A very good copy. With the early ink signature of Mary Ann Symonds on the front free endleaf. This is the fourth of five illustrated editions with the life by Richardson. It was first published in 1739 (title dated 1740), and again in 1749, 1753 (two issues) and 1775. All editions are rare, with ESTC listing four copies of the first, two of the second, five of the third and six of the fifth. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'.