Analyzing the Film Adaptations of Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flowers for Algernon.Pdf

SHORT STORY FFlowerslowers fforor AAlgernonlgernon by Daniel Keyes When is knowledge power? When is ignorance bliss? QuickWrite Why might a person hesitate to tell a friend something upsetting? Write down your thoughts. 52 Unit 1 • Collection 1 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand subplots and Reader/Writer parallel episodes. Reading Skills Track story events. Notebook Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Subplots and Parallel Episodes A long short story, like the misled (mihs LEHD) v.: fooled; led to believe one that follows, sometimes has a complex plot, a plot that con- something wrong. Joe and Frank misled sists of intertwined stories. A complex plot may include Charlie into believing they were his friends. • subplots—less important plots that are part of the larger story regression (rih GREHSH uhn) n.: return to an earlier or less advanced condition. • parallel episodes—deliberately repeated plot events After its regression, the mouse could no As you read “Flowers for Algernon,” watch for new settings, charac- longer fi nd its way through a maze. ters, or confl icts that are introduced into the story. These may sig- obscure (uhb SKYOOR) v.: hide. He wanted nal that a subplot is beginning. To identify parallel episodes, take to obscure the fact that he was losing his note of similar situations or events that occur in the story. intelligence. Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described deterioration (dih tihr ee uh RAY shuhn) on page 55 as you read this story. n. used as an adj: worsening; declining. Charlie could predict mental deterioration syndromes by using his formula. -

Courtney Harding, Is Excited to Start Her Second Year As a TACT Academy Instructor

Denise S Bass, has several television credits to her name including Matlock, One Tree Hill, HBO's East Bound and Down with Danny McBride and Katy Mixon, and TNT's production of T-Bone and Weasel starring Gregory Hines, Christopher Lloyd, and Wayne Knight. Also to her credit are several film productions including The Road to Wellville with Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Broderick, Black Knight with Martin Laurence, and The 27 Club with Joe Anderson. She has been performing theatrically since 1981 working from NC to Florida and touring the Southeast with the American Family Theatre out of Philadelphia. Denise's most recent roles include Ethel in Thalian Association's production of "Barefoot in the Park" (Winner 2017 Thalian Award Best Actress in a Play), Dottie in Thalian Association's production of "Noises Off" (Nominee 2016 Thalian Award Best Supporting Actress in a Play), and Madam Thenadier in Opera House Theatre Company's production of Les Miserable. Other notable roles over the years include Sally in "Follies", Dolly Levi in "Hello, Dolly!", Molly Brown in "The Unsinkable Molly Brown", Delightful in "Dearly Departed", Diana Morales in "A Chorus Line", and Mrs. Meers in "Throughly Modern Mille”. She is a producer and featured performer with Ensemble Audio Studios and was part of the cast for the audio production of "The King's Child", which was selected in 2017 at the Hear Now Audio Festival for the Gold Circle Page. She also voiced several characters for the very popular audio book "Percy the Cat and the Big White House". She is currently writing a collection of short stories and looks forward to teaching Fundamentals of Acting for TACT. -

Universal Realty NBC 8 KGW News at Sunrise Today Gloria Estefan, Emilio Estefan, Bob Dotson Today Show II (N) Today Show III (N) Paid Million

Saturday, April 11, 2015 TV TIME MONDAY East Oregonian Page 7C Television > Today’s highlights Talk shows Gotham siders a life outside of White Pine 6:00 a.m. (42) KVEW Good Morning Gene Baur discuss pantry staples that Northwest will help you live a healthier life. (11) KFFX KPTV 8:00 p.m. Bay, Dylan (Max Thieriot) and WPIX Maury WPIX The Steve Wilkos Show A woman A cold case is re-opened as Gor- Emma (Olivia Cooke) help Nor- 6:30 a.m. (42) KVEW Good Morning has reason to believe that her husband don (Ben McKenzie) and Bullock man (Freddie Highmore) through Northwest is cheating and is trying to kill her. 7:00 a.m. (19) KEPR KOIN CBS This 1:00 p.m. KPTV The Wendy Williams (Donal Logue) investigate a serial a rough night. Also, Caleb (Kenny Morning Show killer known as Ogre in this new Johnson) faces a new threat. (25) KNDU KGW Today Show Gloria (19) KEPR KOIN The Talk (59) episode. At the same time, Fish and Emilo Estefan discuss, ‘On Your OPB Charlie Rose TURN: Washington’s Feet.’ WPIX The Steve Wilkos Show (Jada Pinkett Smith) plots her es- (42) KVEW KATU Good Morning 2:00 p.m. KOIN (42) KVEW The Doctors cape from The Dollmaker. Spies America KGW The Dr. Oz Show AMC 9:00 p.m. ESPN2 ESPN First Take KATU The Meredith Vieira Show (19) Hoarding: Buried Alive - Abe (Jamie Bell) is determined to WPIX Maury 3:00 p.m. KEPR KOIN Dr. Phil 8:00 a.m. -

ALPHABETICAL LIST of Dvds and Vts 9/6/2011 DVD a Mighty Heart

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF DVDs AND VTs 9/6/2011 DVD A Mighty Heart: Story of Daniel Pearl A Nurse I am – Documentary and educational film about nurses A Single Man –with Colin Firth and Julianne Moore (R) Abe and the Amazing Promise: a lesson in Patience (VeggieTales) Akeelah and the Bee August Rush - with Freddie Highmore, Keri Russell, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Terrence Howard, Robin Williams Australia - with Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman Aviator (story of Howard Hughes - with Leonardo DiCaprio Because of Winn-Dixie Beethoven - with Charles Grodin, Bonnie Hunt Big Red Black Beauty Cats & Dogs Changeling - with Angelina Jolie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory - with Johnny Depp Charlie Wilson’s War - with Tom Hanks, Julie Roerts, Phil Seymour Hoffman Charlotte’s Web Chicago Chocolat - with Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, Alfred Molina, Lena Olin & Johnny Depp Christmas Blessing - with Neal Patrick Harris Close Encounters of the Third Kind – with Richard Dreyfuss Date Night – with Steve Carell and Tina Fey (PG-13) Dear John – with Channing Tatum and Amanda Seyfried (PG-13) Doctor Zhivago Dune Duplicity - with Julia Roberts and Clive Owen Enchanted Evita Finding Nemo Finding Neverland Fireproof – with Kirk Cameron on Erin Bethea (PG) Five People You Meet in Heaven Fluke Girl With a Pearl Earring – with Colin Firth, Scarlett Johannson, Tom Wilkinson Grand Torino (with Clint Eastwood) Green Zone – with Matt Damon (R) Happy Feet Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hildalgo with Viggo Mortensen (PG13) Holiday, The – with Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet, -

Before Night Falls

Before Night Falls Dir: Julian Schnabel, 2000 A review by A. Mary Murphy, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada There are two remarkable things about Before Night Falls, based on Reinaldo Arenas's homonymous memoir, and one remarkable reason for them. First, director Julian Schnabel maintains a physically-draining tension throughout much of the film; and second, he grants a centrality to writing that Arenas himself demands. He is able to accomplish these things because his Arenas is Javier Bardem. The foreknowledge that this is a film about a man in Castro's Cuba, and a man in prison there for a time, prepares an audience for explicit tortures that never come. The expectation persists, as it must have for the imprisoned and persecuted man, so that the emotional tension experienced by the audience provides a tiny entry into the overpowering and relentless tension of daily life for Arenas and everyone else who is not a perfect fit for the Revolutionary mold. In the midst of this the writer finds refuge in his writing. Before Night Falls is the story of a writer who has been persecuted even for being a writer, never mind for what he wrote or how he lived, and who writes regardless of the risks and costs. In the childhood backgrounding segment of the film, Schnabel clearly establishes this foundation by showing a grandfather who is so opposed to having a poet in his house that he relocates the family in order to remove young Reinaldo from the influence of a teacher who dares to speak of the boy's gift. -

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

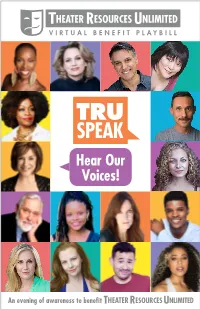

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04

LOST “Raised by Another” CAST LIST BOONE................................Ian Somerhalder CHARLIE..............................Dominic Monaghan CLAIRE...............................Emilie de Ravin HURLEY...............................Jorge Garcia JACK.................................Matthew Fox JIN..................................Daniel Dae Kim KATE.................................Evangeline Lilly LOCKE................................Terry O’Quinn MICHAEL..............................Harold Perrineau SAWYER...............................Josh Holloway SAYID................................Naveen Andrews SHANNON..............................Maggie Grace SUN..................................Yunjin Kim WALT.................................Malcolm David Kelley THOMAS............................... RACHEL............................... MALKIN............................... ETHAN................................ SLAVITT.............................. ARLENE............................... SCOTT................................ * STEVE................................ * www.pressexecute.com LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04 LOST “Raised by Another” SET LIST INTERIORS THE VALLEY - Late Afternoon/Sunset CLAIRE’S CUBBY - Night/Dusk/Day ENTRANCE * ROCK WALL - Dusk/Night/Day * INFIRMARY CAVE - Morning JACK’S CAVE - Night * LOFT - Day - FLASHBACK MALKIN’S HOUSE - Day - FLASHBACK BEDROOM - Night - FLASHBACK LAW OFFICES CONFERENCE ROOM - Day - FLASHBACK EXTERIORS JUNGLE - Night/Day ELSEWHERE - Day CLEARING - Day BEACH - Day OPEN JUNGLE - Morning * SAWYER’S -

Bakalářská Práce

JIHOČESKÁ UNIVERZITA V ČESKÝCH BUDĚJOVICÍCH PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Tim Burton's Film Adaptations of Literary Works / Filmové adaptace literárních děl v režii Tima Burtona Autor práce: Pavel Sirotek Ročník: 3. Studijní kombinace: Český jazyk – Anglický jazyk Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph. D. Rok odevzdání práce: 2013 PROHLÁŠENÍ Prohlašuji, že svoji bakalářskou práci jsem vypracoval pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. České Budějovice, dne 29. dubna 2013 ……………………………………………. Pavel Sirotek PODĚKOVÁNÍ Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval Mgr. Alici Sukdolové, Ph.D. za inspiraci, ochotu při vedení mé bakalářské práce a pomoc s jejím vypracováním. ANOTACE Cílem práce -

Alumni Spotlight: Derek Frey ’95

Alumni Spotlight: Derek Frey ’95 Please provide your biographical information. Home Town: Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania Current Town: London, UK Major: Communication Studies Minor: Journalism Bio: Filmmaker Derek Frey has a long and successful working relationship with director Tim Burton, running Tim Burton Productions since 2001. Most recently Derek co-produced Frankenweenie, which received an Academy Award nomination for Best Animated Picture in 2012. That same year he produced the music video Here With Me for The Killers. Derek is currently serving as Executive Producer on Big Eyes, starring Christoph Waltz and Amy Adams, slated for release this Christmas. Up next he'll Executive Produce Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children starring Eva Green and Asa Butterfield. Derek has worked on over 15 feature films, including as Associate Producer on Alice in Wonderland, Dark Shadows, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, Corpse Bride, and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. His credits also include producer on the documentary A Conversation with Danny Elfman and Tim Burton; writer of the Frankenweenie-based short film Captain Sparky vs. the Flying Saucers; and editor of the comprehensive and award-winning publication The Art of Tim Burton. Derek worked closely with curators from the Museum of Modern Art for the creation of the Tim Burton touring exhibit, which has made record-breaking stops in New York City, Toronto, Melbourne, Paris, Los Angeles, Seoul, Prague and Tokyo. Derek has directed his own films and music videos, including The Ballad of Sandeep, which has appeared in over 35 film festivals and brought home 16 awards, including Best Director at the Independent Film Quarterly Festival and Best Featurette at the Las Vegas International Cinefest. -

CITATION MLA Basics

CITATION MLA Basics 1. Create your Works Cited page before you start writing your essay. 1.1. Determine what type of source you are looking at. This is the hardest and most important part of citation! For example, there are significant differences between videos you watched on DVD, streaming online, or in theaters. 1.2. Use a style manual or style handbook to create the works cited entry. No one memorizes the rules, especially since they are updated every few years to keep up with new technology. Instead, learn how to use the style manual! 1.3. Organize your list alphabetically. If you have two authors with the same last name, look at their first names. If you have two sources by the same author, look at the title, and so on. 1.4. Format the list using hanging indents. This indent style requires that the first line of the citation is leftaligned, but any additional lines are indented by ½ inch. 2. Format your essay using MLA document style. 3. Create intext citations. 3.1. The first time you reference any source, either with a direct quote or a paraphrase, you should use a signal phrase to indicate the credibility of the source. For example, you might write: 3.2. After the first use of a source, you may choose between either signal phrases or parenthetical citation for your intext citations. 3.3. To determine what appears in the intext citation, use the first piece of information up to the first piece of punctuation from the Works Cited entry! In most cases, this will be the author’s last name. -

The Bamboozle Festivals and Roadshow

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: Erin McCarty, (206) 270-4655 Patricia Bowles, (818) 549-5817 Or John Vlautin at Live Nation, (310) 867-7127 Jennifer Gery-Egan at 212-986-6667 WONKA® NAMED PRESENTING SPONSOR OF THIS YEAR’S THE BAMBOOZLE FESTIVALS AND ROADSHOW Magical Candy Maker Promises New Surprises at Festivals and Annual Roadshow (GLENDALE, Calif.) – March 24, 2009 – WONKA and Live Nation announced today that the candy maker has been named the presenting sponsor of The Bamboozle, a festival and tour born five years ago that connects artists and their fans like no other. The Bamboozle presented by WONKA is the only place to experience more than 200 of the most talked about bands in pop, punk, mainstream, emo and more, performing live on multiple stages. The Bamboozle presented by WONKA will be held at the Meadowlands Sports Complex in East Rutherford, N.J., on May 2 and May 3 with headliners Fall Out Boy and No Doubt, who will be performing their first show in five years. The Bamboozle Left presented by WONKA is set for The Festival Grounds at Verizon Wireless Amphitheater in Irvine, Calif., on April 4 and April 5 with headliners Fall Out Boy, 50 Cent and Deftones. A 22-market Bamboozle Roadshow presented by WONKA will take The Bamboozle’s unparalleled party experience across the country, with club dates scheduled nationally beginning on April 5 in Tucson, Ariz., culminating on April 30 in Farmingdale, N.Y., featuring We The Kings, Forever The Sickest Kids, The Cab, Never Shout Never and Mercy Mercedes. -

Raptis Rare Books Holiday 2017 Catalog

1 This holiday season, we invite you to browse a carefully curated selection of exceptional gifts. A rare book is a gift that will last a lifetime and carries within its pages a deep and meaningful significance to its recipient. We know that each person is unique and it is our aim to provide expertise and service to assist you in finding a gift that is a true reflection of the potential owner’s personality and passions. We offer free gift wrapping and ship worldwide to ensure that your thoughtful gift arrives beautifully packaged and presented. Beautiful custom protective clamshell boxes can be ordered for any book in half morocco leather, available in a wide variety of colors. You may also include a personal message or gift inscription. Gift Certificates are also available. Standard shipping is free on all domestic orders and worldwide orders over $500, excluding large sets. We also offer a wide range of rushed shipping options, including next day delivery, to ensure that your gift arrives on time. Please call, email, or visit our expert staff in our gallery location and allow us to assist you in choosing the perfect gift or in building your own personal library of fine and rare books. Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, Florida 33480 561-508-3479 | [email protected] www.RaptisRareBooks.com Contents Holiday Selections ............................................................................................... 2 History & World Leaders...................................................................................12