10426.Ch01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

In the Aftermath of the Emanuel Nine in the September

For Immediate Release: September 21, 2015 Press Contacts: Natalie Raabe, (212) 286-6591 Molly Erman, (212) 286-7936 Adrea Piazza, (212) 286-4255 In the Aftermath of the Emanuel Nine In the September 28, 2015, issue of The New Yorker, in “Blood at the Root” (p. 26), David Remnick travels to Charleston, South Caro- lina, and explores the city’s resistance and resilience in the aftermath of the June murders of nine people at Emanuel A.M.E. Church. Like many people in Charleston, Pastor Norvel Goff, Sr., at Emanuel, says that members of the community remain in shock and immense pain “(‘post-traumatic-stress syndrome’ was the term they often used), but they were alive, and feeling joy in their pews—and at their jobs, and at their Bible classes and dinner tables and Sunday strolls—because of the depth of their spiritual lives,” Remnick writes. “This was the way of a church that had been around since the days when enslaved black men and women, in a quest for safety, community, dignity, co- hesion, empowerment, ritual, and peace, broke from white churches and built ‘invisible’ institutions, sometimes called ‘hush harbors.’ ” The black church, even as it has changed, aged, and, in some places, lost ground to mega-churches, Remnick writes, remains a powerful insti- tution of black life, and of black political influence. The families of the Emanuel Nine shocked the nation with their message of forgive- ness at the killer Dylann Roof ’s hearing the day after the murders. That forgiveness is hard to understand for anyone “who hasn’t had to cope with that kind of powerlessness,” James H. -

Benjamin Britten and Luchino Visconti: Iterations of Thomas Mann's Death in Venice James M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Benjamin Britten and Luchino Visconti: Iterations of Thomas Mann's Death in Venice James M. Larner Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BENJAMIN BRITTEN AND LUCHINO VISCONTI: ITERATIONS OF THOMAS MANN’S DEATH IN VENICE By JAMES M. LARNER A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of James M. Larner defended on 17 April 2006. Caroline Picart Professor Directing Dissertation Jane Piper Clendinning Outside Committee Member William Cloonan Committee Member Raymond Fleming Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is lovingly dedicated to my wife Janet and my daughter Katie. Their patience, support, and love have been the one constant throughout the years of this project. Both of them have made many sacrifices in order for me to continue my education and this dedication does not begin to acknowledge or repay the debt I owe them. I only hope they know how much I appreciate all they have done and how much I love them. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the four members of my dissertation committee for their role in the completion of this document. The guidance of Kay Picart as director of the committee was crucial to the success of this project. -

For All the Attention Paid to the Striking Passage of Thirty-Four

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons for Jane, on our thirty-fourth Accents of Remorse The good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect. First Sightings For all the attention paid to the “interview” scene in Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, its musical depths have proved remarkably resistant to analysis and have remained unplumbed. This striking passage of thirty-four whole-note chords has probably attracted more comment than any other in the opera since Andrew Porter first spotted shortly after the 1951 premiere that all the chords harmonize members of the F major triad, leading to much discussion over whether or not the passage is “in F major.” 1 Beyond Porter’s perception, the structure was far from obvious, perhaps in some way unprecedented, and has remained mysterious. Indeed, it is the undisputed gnomic power of its strangeness that attracted (and still attracts) most comment. Arnold Whittall has shown that no functional harmonic or contrapuntal explanation of the passage is satisfactory, and proceeded from there to make the interesting assertion that that was the point: The “creative indecision”2 that characterizes the music of the opera was meant to confront the listener with the same sort of difficulty as the layers of irony in Herman Melville’s “inside narrative,” on which the opera is based. To quote a single sentence of the original story that itself contains several layers of ironic ambiguity, a sentence thought by some—I believe mistakenly—to say that Vere felt no remorse: 1. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Peter Grimes Page 1 of 2 Opera Assn

San Francisco War Memorial 1976 Peter Grimes Page 1 of 2 Opera Assn. Opera House New production made possible in 1973 through a generous gift from the Gramma Fisher Foundation of Marshalltown, Iowa, made jointly to the Chicago Lyric and San Francisco Operas. Peter Grimes (in English) Opera in three acts by Benjamin Britten Libretto by Montagu Slater Based on a poem by George Crabbe Conductor CAST John Pritchard Hobson Paul Geiger Production Swallow Alexander Malta Geraint Evans Peter Grimes Jon Vickers Set Designer Mrs. Sedley Donna Petersen Carl Toms Ellen Orford Heather Harper Chorus Director A fisherman John Del Carlo Robert Jones Auntie Sheila Nadler Lighting Designer Bob Boles Paul Crook Thomas J. Munn Captain Balstrode Geraint Evans Musical Preparation Rev. Horace Adams Joseph Frank Thomas Fulton First Niece Claudia Cummings Costume Designer Second Niece Pamela South Tanya Moiseiwitsch Ned Keene Wayne Turnage Boy Steven Cohen Edward Lampe (10/22) A lawyer John Duykers Dr. Thorpe Janusz Offstage voice Luana De Vol Janice Aaland *Role debut †U.S. opera debut PLACE AND TIME: The Borough, a small fishing town on the east coast of England, towards 1830 Wednesday, October 6 1976, at 8:00 PM PROLOGUE -- A room inside Moot Hall Saturday, October 9 1976, at 8:00 PM Act I, Scene 1 -- The Borough beach and street Wednesday, October 13 1976, at 8:00 PM Scene 2 -- Inside "The Boar" Sunday, October 17 1976, at 2:00 PM INTERMISSION Friday, October 22 1976, at 8:00 PM Act II, Scene 1 -- The Borough beach and street Scene 2 -- Peter Grimes's hut INTERMISSION Act III, Scene 1 -- The Borough beach and street Scene 2 -- Later that night San Francisco War Memorial 1976 Peter Grimes Page 2 of 2 Opera Assn. -

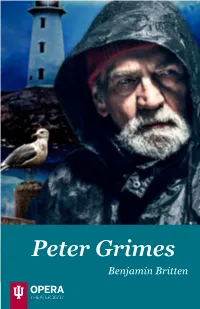

Peter Grimes Benjamin Britten

Peter Grimes Benjamin Britten THEATER 16/17 FOR YOUR INFORMATION Do you want more information about upcoming events at the Jacobs School of Music? There are several ways to learn more about our recitals, concerts, lectures, and more! Events Online Visit our online events calendar at music.indiana.edu/events: an up-to-date and comprehensive listing of Jacobs School of Music performances and other events. Events to Your Inbox Subscribe to our weekly Upcoming Events email and several other electronic communications through music.indiana.edu/publicity. Stay “in the know” about the hundreds of events the Jacobs School of Music offers each year, most of which are free! In the News Visit our website for news releases, links to recent reviews, and articles about the Jacobs School of Music: music.indiana.edu/news. Musical Arts Center The Musical Arts Center (MAC) Box Office is open Monday – Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Call 812-855-7433 for information and ticket sales. Tickets are also available at the box office three hours before any ticketed performance. In addition, tickets can be ordered online at music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. Entrance: The MAC lobby opens for all events one hour before the performance. The MAC auditorium opens one half hour before each performance. Late Seating: Patrons arriving late will be seated at the discretion of the management. Parking Valid IU Permit Holders access to IU Garages EM-P Permit: Free access to garages at all times. Other permit holders: Free access if entering after 5 p.m. any day of the week. -

15 Tips for 5 Cities

#6 Companion Magazine #6 / 2015 Free for guests of 25h hotels € 5,50 / £ 4,00 $ 6,00 CHF companion-magazine.com A magazine by freundevonfreunden.com for 25hours Hotels featuring Fashion & Style, Food & Drink, Art & Entertainment, Wellness & Activity, People & Business from Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Vienna, Zurich & beyond Beyond Kale & A Way Success Company With Wood Highly successful entre- Yoga teacher and chef Belén Berlin Lumberjacks – preneur Bobby Dekeyser on Vázquez Amaro shares one Albrecht von Alvensleben the intricacies of valuing of her favorite dishes – and Max Pauen aka Bullen- material possessions. a winter special. berg make the cut in oak. A tour to the family forest. Interview, p. 13 Recipe, p. 16 Portrait, p. 26 15 TIPS WOVEN FOR 5 CITIES PLAY- Bits & Pieces, p. 4 GROUNDS One could call them playing fields – the nature-inspired, woven rugs and textile objects by Alexandra Kehayoglou. The designer specializes in items that usually just lay flat THE DO-IT-YOURSELF WOMAN on the ground, adding a third dimension and a touch of nature to any home. Lately, her craft has also extended to Pop star, feminist, do-it-yourself heroine, poster girl of art and fashion installations. COMPANION met with the the internet generation: Claire Boucher does it all. She Argentinian rising star in her Buenos Aires studio to speak achieved stardom in 2012 with her indie music project about heritage and happy accidents. Grimes. With “Art Angels,” the long-awaited follow-up to her breakthrough album “Visions,” the Canadian has once Spielwiesen könnte man sie nennen – die von der Natur in- again shown how a woman in the pop music industry can spirierten gewebten Teppiche und textilen Objekte von take her career into her own hands. -

5099943343256.Pdf

Benjamin Britten 1913 –1976 Winter Words Op.52 (Hardy ) 1 At Day-close in November 1.33 2 Midnight on the Great Western (or The Journeying Boy) 4.35 3 Wagtail and Baby (A Satire) 1.59 4 The Little Old Table 1.21 5 The Choirmaster’s Burial (or The Tenor Man’s Story) 3.59 6 Proud Songsters (Thrushes, Finches and Nightingales) 1.00 7 At the Railway Station, Upway (or The Convict and Boy with the Violin) 2.51 8 Before Life and After 3.15 Michelangelo Sonnets Op.22 9 Sonnet XVI: Si come nella penna e nell’inchiostro 1.49 10 Sonnet XXXI: A che piu debb’io mai l’intensa voglia 1.21 11 Sonnet XXX: Veggio co’ bei vostri occhi un dolce lume 3.18 12 Sonnet LV: Tu sa’ ch’io so, signior mie, che tu sai 1.40 13 Sonnet XXXVIII: Rendete a gli occhi miei, o fonte o fiume 1.58 14 Sonnet XXXII: S’un casto amor, s’una pieta superna 1.22 15 Sonnet XXIV: Spirto ben nato, in cui so specchia e vede 4.26 Six Hölderlin Fragments Op.61 16 Menschenbeifall 1.26 17 Die Heimat 2.02 18 Sokrates und Alcibiades 1.55 19 Die Jugend 1.51 20 Hälfte des Lebens 2.23 21 Die Linien des Lebens 2.56 2 Who are these Children? Op.84 (Soutar ) (Four English Songs) 22 No.3 Nightmare 2.52 23 No.6 Slaughter 1.43 24 No.9 Who are these Children? 2.12 25 No. -

Owen Wingrave

OWEN WINGRAVE Oper in zwei Akten von Benjamin Britten Libretto von Myfanwy Piper nach der gleichnamigen Kurzgeschichte von Henry James Eine Veranstaltung des Departements für Oper und Musiktheater in Kooperation mit dem Departement für Bühnen- und Kostümgestaltung, Film- und Ausstellungsarchitektur Montag, 20. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Dienstag, 21. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Mittwoch, 22. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr (Livestream) Donnerstag, 23. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Max Schlereth Saal Universität Mozarteum Mirabellplatz 1 BESETZUNG Owen Wingrave Taesung Kim (20.1./22.1.)/Benjamin Sattlecker (21.1./23.1.) Musikalische Einstudierung Julia Antonovitch, Dariusz Burnecki, Stefan Müller, Walewein Witten Spencer Coyle Xiaofei Liu (20.1./22.1.)/Qi Wang (21.1./23.1.) Szenische Assistenz Agnieszka Lis Lechmere Johannes Hubmer Schauspielcoaching Natalie Forester Miss Wingrave Julia Heiler Sprachcoaching Theresa McDougall Mrs. Coyle Veronika Loy (20.1./22.1.)/Sophie Negoïta (21.1./23.1.) Szenischer Kampf Ulf Kirschhofer Mrs. Julian Chelsea Kolic´ (20.1./22.1.)/Bryndís Guðjónsdóttir (21.1./23.1.) Maske Jutta Martens Kate Vera Bitter Übertitel Leopold Eibensteiner General Wingrave Yu Hsuan Cheng Technische Leitung Andreas Greiml/Thomas Hofmüller/Alexander Lährm Narrator Richard Glöckner Werkstättenleitung Thomas Hofmüller Kinderchor Antonella Hohenadler, Felix Knittel, Florian Kritzinger, Lennart Malm, Sophie Münch, Noah Obermair, Niklas Plasse, Lichtgestaltung Michael Becke Leonhard Radauer Tontechnik Susanne Gasselsberger Musikalische Leitung Gernot Sahler -

Copland As Mentor to Britten, 1939-1942

'You absolutely owe it to England to stay here': Copland as mentor to Britten, 1939-1942 Suzanne Robinson Few details of the circumstances of Benjamin Copland to visit him for the weekend at his home in a Britten's stay in America in the years 1939-42 were converted mill in Snape. On this occasion they familiar- known before the publication in 1991of Britten's letters ised one another with their music; Copland played his and, in 1992, of a biography by Humphrey Carpenter. school opera, The Second Hurricane, singing all the parts And with the exception of a short article on Aaron himself, while Britten performed the first version of his Copland and Britten in an Aldeburgh Festival Programme Piano ~oncerto.~Being July, and England, at the first ~ook,llittle attention has been paid to the significance sign of sunshine the locals escorted their visitor to one of Britten's exposure to Copland's music, which Britten of Suffolk's pebbled beaches (which Copland described regarded as the best America had to offer. More than 20 as a 'shingle'). Copland realised that perhaps he was letters survive between 'Benjie' and 'my dearest Aaron', more accustomed to the effects of the sun, when Ibefore the majority of them belonging to the war years when long it became clear that the assembled group was in Copland was resident in New York and Britten was, for danger of "roasting". When I politely pointed out the the most part, nearby in Long ~sland.~Britten fre- obvious result to be expected from lying unprotected quently referred to Copland as his 'very dear friend', on the beach, I was told: "But we see the sun so and even 'Father' (Copland was the senior of the two rarely"'? When he returned to America, copland wrote by 13 years). -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon.