Lambda Alpha Journal, V.33, 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions "In the Midst of a Loneliness" The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument Historic Structures Report James E. Ivey 1988 Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15 Southwest Regional Office National Park Service Santa Fe, New Mexico TABLE OF CONTENTS sapu/hsr/hsr.htm Last Updated: 03-Sep-2001 file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsr.htm [9/7/2007 2:07:46 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Figures Executive Summary Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: Administrative Background Chapter 2: The Setting of the Salinas Pueblos Chapter 3: An Introduction to Spanish Colonial Construction Method Chapter 4: Abó: The Construction of San Gregorio Chapter 5: Quarai: The Construction of Purísima Concepción Chapter 6: Las Humanas: San Isidro and San Buenaventura Chapter 7: Daily Life in the Salinas Missions Chapter 8: The Salinas Pueblos Abandoned and Reoccupied Chapter 9: The Return to the Salinas Missions file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsrt.htm (1 of 6) [9/7/2007 2:07:47 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) Chapter 10: Archeology at the Salinas Missions Chapter 11: The Stabilization of the Salinas Missions Chapter 12: Recommendations Notes Bibliography Index (omitted from on-line -

New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942 University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1942 The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 2-6-1942 New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1942 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942." 44, 36 (1942). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1942/8 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1942 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~·· i -,~------------------------------~------~(~~--~--~~~ J UNIVERSITY OF N£W M~XICO UBR\RV Page Four ~EW MEXICO LOBO Tuesday, February 3, 1942 • • • The Time Is Being Used Now. • • Student Opinion Vero~ica and Camelia Conspire, • By GWENN PERRY During the past two weeks the LOBO has dition of responsibility will feel in times of for this "stalemate"·has been obvious. Lobo Poll Editor mal'ntained a strictly opinionated attitude inaugural. The LOBO, like other newspapers striv- Question: What policy should the ticket committee follow In regard to admittances to the Junior.. Sen,ior Prom this year? Should it be kept toward its campaign for cheaper prices on Now, a new "strategy" of facts is needed. ing for improvement and reform, must traditional for upperclassmen? What effect do you think admitting on- Perspire in Readiness for Debut school materials here on the campus. -

Albuquerque Tricentennial

Albuquerque Tricentennial Fourth Grade Teachers Resource Guide September 2005 I certify to the king, our lord, and to the most excellent señor viceroy: That I founded a villa on the banks and in the valley of the Rio del Norte in a good place as regards land, water, pasture, and firewood. I gave it as patron saint the glorious apostle of the Indies, San Francisco Xavier, and called and named it the villa of Alburquerque. -- Don Francisco Cuervo y Valdes, April 23, 1706 Resource Guide is available from www.albuquerque300.org Table of Contents 1. Albuquerque Geology 1 Lesson Plans 4 2. First People 22 Lesson Plan 26 3. Founding of Albuquerque 36 Lesson Plans 41 4. Hispanic Life 47 Lesson Plans 54 5. Trade Routes 66 Lesson Plan 69 6. Land Grants 74 Lesson Plans 79 7. Civil War in Albuquerque 92 Lesson Plan 96 8. Coming of the Railroad 101 Lesson Plan 107 9. Education History 111 Lesson Plan 118 10. Legacy of Tuberculosis 121 Lesson Plan 124 11. Place Names in Albuquerque 128 Lesson Plan 134 12. Neighborhoods 139 Lesson Plan 1 145 13. Tapestry of Cultures 156 Lesson Plans 173 14. Architecture 194 Lesson Plans 201 15. History of Sports 211 Lesson Plan 216 16. Route 66 219 Lesson Plans 222 17. Kirtland Air Force Base 238 Lesson Plans 244 18. Sandia National Laboratories 256 Lesson Plan 260 19. Ballooning 269 Lesson Plans 275 My City of Mountains, River and Volcanoes Albuquerque Geology In the dawn of geologic history, about 150 million years ago, violent forces wrenched the earth’s unstable crust. -

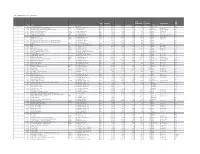

UNM Building List

UNM Building List Non- Bldg Assignable Assignable Efficiency Campus Site Name Street City State Zip Year Built Status Gross Sq Ft Usable Sq Ft Sq Ft Sq Ft Ratio Group Albuquerque A0002 - Engineering and Science Computer Pod 201 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1916 OPEN 7,423 6,550 5,762 788 78% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0004 - Elizabeth Waters Center for Dance at Carlisle Gymnasium 301 Yale Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1928 OPEN 37,545 34,805 28,302 6,503 75% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0008 - Bandelier Hall East 401 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1930 OPEN 10,084 8,510 6,276 2,234 62% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0009 - Marron Hall 201 Yale Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1931 OPEN 27,475 19,405 11,577 7,828 42% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0010 - Scholes Hall 1800 Roma Ave. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1936 OPEN 51,160 45,023 32,546 12,477 65% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0011 - Anthropology 500 University Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1937 OPEN 57,668 50,900 40,347 10,553 70% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0012 - Anthropology Annex 301 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1937 OPEN 9,321 8,046 6,033 2,013 65% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0014 - Science and Mathematics Learning Center 311 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 2010 OPEN 74,662 66,271 43,606 22,665 58% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0015 - Hibben Center for Archaeology Research 450 University Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 2001 OPEN 37,922 34,751 26,565 8,186 70% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0016 - Bandelier Hall West 400 University Blvd. -

08-UNM Building List by Site 11-14-12

UNM Building List by Campus, by Building Number revised 11-14-2012 Site Buildin Building Name Building Building Address Year Net Non- Net Useable Gross Building Ownership Campus g Acronym Built Assignable Assignable Square Feet Square Feet Efficiency Map Grid Square Feet Square Feet (GSF) Ratio Coordinate (NASF) A - 0002 ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE COMPUTER POD ESCP 201 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1916 5,762 788 6,550 7,423 78% OWN J-16 ALBUQUERQUE 0004 ELIZABETH WATERS CENTER FOR DANCE AT CARL 301 YALE BLVD. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1928 28,356 6,449 34,805 37,545 76% OWN K-16 CARLISLE GYMNASIUM 0008 BANDELIER HALL EAST BANDE 401 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1930 5,340 3,170 8,510 10,084 53% OWN J-15 0009 MARRON HALL MARN 201 YALE BLVD. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1931 11,406 7,999 19,405 27,475 42% OWN K-17 0010 SCHOLES HALL SCHL 1800 ROMA AVE. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1936 32,810 11,378 44,188 51,160 64% OWN K-14 0011 ANTHROPOLOGY ANTHO 500 UNIVERSITY BLVD. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1937 40,263 10,293 50,556 57,693 70% OWN J-14 0012 ANTHROPOLOGY ANNEX ANTHX 301 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1937 6,042 2,013 8,055 9,321 65% OWN J-16 0014 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS LEARNING CENTER 311 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 2010 37,981 17,442 55,423 61,840 61% OWN J-15 0015 HIBBEN CENTER FOR ARCHAEOLOGY RESEARCH HIBB 450 UNIVERSITY BLVD. -

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement Volume III August 2012 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Albuquerque District Rio Puerco Field Office TABLE OF CONTENTS A CULTURAL RESOURCES ON NON-BLM LANDS LISTED ON THE NRHP ........ A-1 B DESCRIPTION OF GRAZING ALLOTMENTS BY ACREAGE AND AUMS ......... B-1 C EXAMPLES OF PRESCRIBED GRAZING SYSTEMS .............................................. C-1 C.1 Rest-Rotation Grazing ................................................................................................ C-1 C.2 Deferred Rotation Grazing .......................................................................................... C-1 C.3 Deferred Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.4 Alternate Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.5 Short-Duration, High-Intensity Grazing ..................................................................... C-2 D RANGELAND IMPROVEMENTS ............................................................................... D-1 D.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. D-1 D.2 Structural Improvements ............................................................................................. D-1 D.2.1 Fences .............................................................................................................................. -

New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 078, No 34, 10/10/1974." 78, 34 (1974)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1974 The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 10-10-1974 New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 078, No 34, 10/ 10/1974 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1974 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 078, No 34, 10/10/1974." 78, 34 (1974). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1974/114 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1974 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 74 .I . ~ t: ' " Ne\IV Mexico U.NM Founded; Uv\!,~W . .. 'L D B D ' ' .~J;,1 DAIL.V · .· . Survives Its · ~ C'2... Sf!. '!., Thursday,October 10,1974 First 25 Ye.afs \ By GAIL GOTTLIEB In 1889, Bernard ShandoJl Rode.y spent 36 sleepless hours jn an effort to draft a biD calling for the formation of a 'university in the territoty of New Mexico. A caucus . had only narrowly defeated opposition to the introduction of such a bill, an.d Rodey knew that he must draft and introduce his bill before the opposition had time to regroup, Two days later on February 28, Rodey shambled sleepily out ot the old Palace Hotel in Santa Fe, walked down to the Inn of the Governors and watched with elation as his bill, ••to establish ,( and. provide for the maintenance of the·· University 'of New Mexico., the Agricultural Experiment, the School of Mines, and the Insane Asylum," passed, Many skeptics in the territory were justified in thinking that . -

The Religious Lives of Franciscan Missionaries, Pueblo Revolutionaries, and the Colony of Nuevo Mexico, 1539-1722 Michael P

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Among the Pueblos: The Religious Lives of Franciscan Missionaries, Pueblo Revolutionaries, and the Colony of Nuevo Mexico, 1539-1722 Michael P. Gueno Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES AMONG THE PUEBLOS: THE RELIGIOUS LIVES OF FRANCISCAN MISSIONARIES, PUEBLO REVOLUTIONARIES, AND THE COLONY OF NUEVO MEXICO, 1539-1722 By MICHAEL P. GUENO A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Michael P. Guéno defended on August 20, 2010. __________________________________ John Corrigan Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Edward Gray University Representative __________________________________ Amanda Porterfield Committee Member __________________________________ Amy Koehlinger Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ John Corrigan, Chair, Department of Religion _____________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For Shaynna iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is my pleasure and honor to remember the many hands and lives to which this manuscript and I are indebted. The innumerable persons who have provided support, encouragement, and criticism along the writing process humble me. I am truly grateful for the ways that they have shaped this text and my scholarship. Archivists and librarians at several institutions provided understanding assistance and access to primary documents, especially those at the New Mexico State Record Center and Archive, the Archive of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, Archivo General de la Nacion de Mexico, and Biblioteca Nacional de la Anthropologia e Historia in Mexico City. -

New Mexico Lobo, Volume 066, No 5, 10/2/1962 University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1962 The aiD ly Lobo 1961 - 1970 10-2-1962 New Mexico Lobo, Volume 066, No 5, 10/2/1962 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1962 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Lobo, Volume 066, No 5, 10/2/1962." 66, 5 (1962). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1962/64 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1961 - 1970 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1962 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Page 8 NEW MEXICO LOBO Friday, September 28, 1962 ....... >1""'· ~: j'; ~.-~-. .v·" ',,4.-.oc; . .t.~-J,7 -. .~: !; Ashes to Ashes •• , EXICOLOBO '·'· . Dust to Dust • • • OUR SIXTY-FIFTH YEAR OF EDITORIAL FREEDOM Vol. 66 Tuesday, Octobel' 2, 1962 .. r OBITUARY 6,000 Fle.deral Troops '!'here was no college campus. in Oxford, Mis:;;issii>Pi, la:st night . , , only a dark and eerie military r.amp. Foxholes X'ing the campus of the 114-year-old school .... all entrances are blocked by soldiers and military vehicles Invade U of Mississippi; , .. troops in pairs. and squads roam· the campus. Most of the dormitories and sorority and fraternity houses are vacant. Students have packed their bags and left for an • indefinite pcri11d. SAVE MONEY-ORDER NOW!! -, The~ campus is in ahnost total darkness. About the only light visible was. the oc.casional beam .of a flashlight as a To Quell Wild Disorders SPECIAL REDUCED RATES, ONLY FOR , , , , , •• , , , , , , . -

The UNM Building List by Name

The UNM Building List by Name NON- BLDG UNM YEAR BUILDING ASSIGNABLE EFFICIENCY MAINTENANCE MAP SITE BUILDING NAME ACRONYM STREET BUILT GROSS SF USABLE SF ASSIGNABLE SF SF RATIO OWNERSHIP ZONE GRID A - ALBUQUERQUE 0808 2130 Eubank Blvd NE 2130 Eubank 2014 22,971 20,867 20,132 735 88% OWN-UNMH N/A 0020A ACADEMIC AFFAIRS & STUDENT VETERANS PAYRL 608 BUENA VISTA DR. N.E. 1930 5,496 4,862 3,222 1,640 59% OWN FM Area One K-14 1071 ADDICTION AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE PROGRAM (ASAP) 2600 Yale Blvd SE 2013 25,562 23,670 23,670 93% LEASE-HSC UH UNM Hospital N/A 0159 AEROSPACE STUDIES BUILDING AERO 1901 LAS LOMAS RD. N.E. 1940 4,096 3,464 3,061 403 75% OWN FM Area One I-12 0025 ALUMNI MEMORIAL CHAPEL ALUMNI 1700 ROMA AVE. N.E. 1960 4,316 3,488 2,837 651 66% OWN FM Area Four J-15 0157 ALVARADO HALL DORMITORY ALVRDO 2800 CAMPUS BLVD. N.E. 1965 41,615 36,329 24,393 11,936 59% OWN RLSH Facilities Maintenance P-15 0269 AMBULATORY CARE CENTER ACC 2211 LOMAS BLVD. N.E. 1989 210,686 189,603 115,804 73,799 55% OWN-HSC UH UNM Hospital O-13 0011 ANTHROPOLOGY ANTHO 500 UNIVERSITY BLVD. N.E. 1937 57,668 50,782 40,347 10,435 70% OWN FM Area Four J-14 0012 ANTHROPOLOGY ANNEX ANTHX 301 TERRACE ST. N.E. 1937 9,321 8,046 6,033 2,013 65% OWN FM Area Four J-16 0810 ANTOINE PREDOCK CENTER FOR DESIGN AND DESIGN RESEARCH 300/308 12TH STREET NE 9,637 8,651 8,397 254 87% OWN N/A 0811 ANTOINE PREDOCK CENTER FOR DESIGN AND DESIGN RESEARCH 308 12TH STREET NE 3,500 2,711 2,467 244 70% OWN N/A 0175 ARMY ROTC ARMY 1832, 1834, 1836 LOMAS BLVD. -

LDC Historic Summary REPORT

Historic Summary Getty Campus Heritage Project Many of the residence halls that are being University of New Mexico Campus considered in the redevelopment of student Heritage Preservation Survey housing are included as Type 2 buildings (Alvarado Hall, Coronado Hall, Onate Hall, The Historic Preservation Committee of UNM, Santa Ana Hall, Santa Clara Hall, Laguna with support from the J. Paul Getty Foundation, DeVargas). Although great efforts are being completed the UNM Campus Heritage made to maximize use of current facilities, Preservation Plan in 2007. Through extensive proposals for redevelopment of student housing research and evaluation, the buildings and involve the possibility of removal of several of landscaped zones of central campus were the Type 2 residence halls. Type 2 buildings classified according to historical value, and have been documented and recorded in the given priority based upon historic qualities. UNM Campus Heritage Preservation PLan, and The results were published in the preservation can be referenced for future research, planning, plan, and all surveyed buildings were classified and development. into three types or categories that identify the buildings and landscapes of historic value: In developing housing strategies for UNM, planners are coordinating with the Historic 1. Highest Historically very important to retain, Preservation Committee to best achieve a already state or federally registered historically rich campus. 2. Medium Has historic features that can be archived, replicated or recalled - does not Please visit the following web page for detailed preclude removal if there is a compelling information on historic preservation under need for use of the property on which it sits UNM Planning and Campus Development; or the adjacent lands http://iss.unm.edu/PCD/university-architect/ 3. -

New Mexico (U.S

New Mexico (U.S. National Park Service) Page 1 of 107 New Mexico Bandelier National Monument New Mexico Parks Parks NATIONAL MONUMENT Aztec Ruins (http://www.nps.gov/azru/) Aztec, NM Pueblo people describe this site as part of their migration journey. Today you can follow their ancient passageways to a distant time. Explore a 900-year old ancestral Pueblo Great House of over 400 masonry rooms. Look up and see original timbers holding up the roof. Search for the fingerprints of ancient workers in the mortar. Listen for an echo of ritual drums in the reconstructed Great Kiva. NATIONAL MONUMENT Bandelier (http://www.nps.gov/band/) Los Alamos, NM Bandelier National Monument protects over 33,000 acres of rugged but beautiful canyon and mesa country as well as evidence of a human presence here going back over 11,000 years. Petroglyphs, dwellings carved into the soft rock cliffs, and standing masonry walls pay tribute to the early days of a culture that still survives in the surrounding communities. NATIONAL MONUMENT Capulin Volcano (http://www.nps.gov/cavo/) Capulin, NM Come view a dramatic landscape—a unique place of mountains, plains, and sky. Born of fire and forces continually reshaping the earth’s surface, Capulin Volcano provides access to nature’s most awe-inspiring work. http://www.nps.gov/state/nm/index.htm?program=all 4/ 30/ 2015 New Mexico (U.S. National Park Service) Page 2 of 107 NATIONAL PARK Carlsbad Caverns (http://www.nps.gov/cave/) Carlsbad, NM High rising ancient sea ledges, deep rocky canyons, cactus, grasses and thorny shrubs - who would imagine the hidden treasures deep beneath this rugged landscape? Secretly tucked below the desert terrain are more than 119 known caves - all formed when sulfuric acid dissolved the surrounding limestone.