Pre-Disaster Mitigation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions "In the Midst of a Loneliness" The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument Historic Structures Report James E. Ivey 1988 Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15 Southwest Regional Office National Park Service Santa Fe, New Mexico TABLE OF CONTENTS sapu/hsr/hsr.htm Last Updated: 03-Sep-2001 file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsr.htm [9/7/2007 2:07:46 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Figures Executive Summary Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: Administrative Background Chapter 2: The Setting of the Salinas Pueblos Chapter 3: An Introduction to Spanish Colonial Construction Method Chapter 4: Abó: The Construction of San Gregorio Chapter 5: Quarai: The Construction of Purísima Concepción Chapter 6: Las Humanas: San Isidro and San Buenaventura Chapter 7: Daily Life in the Salinas Missions Chapter 8: The Salinas Pueblos Abandoned and Reoccupied Chapter 9: The Return to the Salinas Missions file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsrt.htm (1 of 6) [9/7/2007 2:07:47 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) Chapter 10: Archeology at the Salinas Missions Chapter 11: The Stabilization of the Salinas Missions Chapter 12: Recommendations Notes Bibliography Index (omitted from on-line -

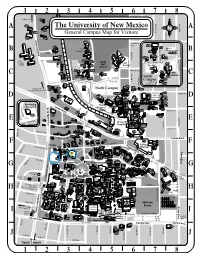

UNM Campus Map.Pdf

12345678 to Bldg. 259 277 Girard Blvd. Princeton Dr. A 278 The University of New Mexico A 255 N 278A General Campus Map for Visitors Vassar Dr. 271 265 University Blvd. 260 Constitution Ave. 339 217 332 Married Casa University Blvd. Student Housing B Esperanza Stanford Dr. 333 B KNME-TV 317-329 270 262 337 218 334 331 Buena Vista Dr. Carrie 240 243 Tingley 272 North Law Avenida De Cesar Chavez Golf 301 Hospital 233 241 239 School “The Pit” Camino de Salud Course 302 237 236B 230 Mountain Rd. 312 307 C 223 Stanford Dr. UNM C 206 Stadium 205 242 Columbia Dr. South 308 238 236A Campus 311 Tucker Rd. Tucker Rd. to South Golf Course 311A C 216 a 276 m 208 210 221 to Bldg. 259 252 in North Campus 219 o 263 1634 University Blvd. NE d e 251 S a 213-215 209 231 Marble Ave. lu Yale Blvd. Bernalillo Cty. D 250 d 249 D Mental Health 246 273 204 248 234 266 Center 225 268 258 Continuing Health 228 U 253 247 n Education Lomas Blvd. i Sciences 229 v 211 e 226 r Center 212 s 264 Frontier Ave. i t y 220 201 B l v 203 d 259 183 . 227 232 Girard Blvd. E N. Yale Entrance E 175 202 Vassar Dr. Mesa Vista Rd. 207 University Indian School Rd. Hospital University Blvd. University Mesa Vista Rd. 235 Revere Pl. 182 224 Sigma Chi Rd. 165 154 256 269 171 Spruce St. 191 151 Si d. Yale Blvd. -

Fire Regimes Approaching Historic Norms Reduce Wildfire-Facilitated

Fire regimes approaching historic norms reduce wildfire-facilitated conversion from forest to non-forest 1, 1 2 3 RYAN B. WALKER, JONATHAN D. COOP, SEAN A. PARKS, AND LAURA TRADER 1School of Environment and Sustainability, Western State Colorado University, Gunnison, Colorado 81231 USA 2Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, Rocky Mountain Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Missoula, Montana 59801 USA 3Fire Ecology Program, Bandelier National Monument, National Park Service, Los Alamos, New Mexico 87544 USA Citation: Walker, R. B., J. D. Coop, S. A. Parks, and L. Trader. 2018. Fire regimes approaching historic norms reduce wildfire-facilitated conversion from forest to non-forest. Ecosphere 9(4):e02182. 10.1002/ecs2.2182 Abstract. Extensive high-severity wildfires have driven major losses of ponderosa pine and mixed-coni- fer forests in the southwestern United States, in some settings catalyzing enduring conversions to non- forested vegetation types. Management interventions to reduce the probability of stand-replacing wildfire have included mechanical fuel treatments, prescribed fire, and wildfire managed for resource benefit. In 2011, the Las Conchas fire in northern New Mexico burned forested areas not exposed to fire for >100 yr, but also reburned numerous prescribed fire units and/or areas previously burned by wildfire. At some sites, the combination of recent prescribed fire and wildfire approximated known pre-settlement fire fre- quency, with two or three exposures to fire between 1977 and 2007. We analyzed gridded remotely sensed burn severity data (differenced normalized burn ratio), pre- and post-fire field vegetation samples, and pre- and post-fire measures of surface fuels to assess relationships and interactions between prescribed fire, prior wildfire, fuels, subsequent burn severity, and patterns of post-fire forest retention vs. -

New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942 University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1942 The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 2-6-1942 New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1942 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942." 44, 36 (1942). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1942/8 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1942 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~·· i -,~------------------------------~------~(~~--~--~~~ J UNIVERSITY OF N£W M~XICO UBR\RV Page Four ~EW MEXICO LOBO Tuesday, February 3, 1942 • • • The Time Is Being Used Now. • • Student Opinion Vero~ica and Camelia Conspire, • By GWENN PERRY During the past two weeks the LOBO has dition of responsibility will feel in times of for this "stalemate"·has been obvious. Lobo Poll Editor mal'ntained a strictly opinionated attitude inaugural. The LOBO, like other newspapers striv- Question: What policy should the ticket committee follow In regard to admittances to the Junior.. Sen,ior Prom this year? Should it be kept toward its campaign for cheaper prices on Now, a new "strategy" of facts is needed. ing for improvement and reform, must traditional for upperclassmen? What effect do you think admitting on- Perspire in Readiness for Debut school materials here on the campus. -

Postwildfire Preliminary Debris Flow Hazard Assessment for the Area Burned by the 2011 Las Conchas Fire in North-Central New Mexico

Postwildfire Preliminary Debris Flow Hazard Assessment for the Area Burned by the 2011 Las Conchas Fire in North-Central New Mexico Open-File Report 2011–1308 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Postwildfire Preliminary Debris Flow Hazard Assessment for the Area Burned by the 2011 Las Conchas Fire in North-Central New Mexico By Anne C. Tillery, Michael J. Darr, Susan H. Cannon, and John A. Michael Open-File Report 2011–1308 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Tillery, A.C., Darr, M.J., Cannon, S.H., and Michael, J.A., 2011, Postwildfire preliminary debris flow hazard assessment for the area burned by the 2011 Las Conchas Fire in north-central New Mexico: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011–1308, 11 p. Frontispiece: Satellite view of Las Conchas Fire (photos by NASA), canyon slopes burned in Bandelier National Monument (photo by National Park Service), valley floor of areas burned in Bandelier National Monument (photo by National Park Service). -

Albuquerque Tricentennial

Albuquerque Tricentennial Fourth Grade Teachers Resource Guide September 2005 I certify to the king, our lord, and to the most excellent señor viceroy: That I founded a villa on the banks and in the valley of the Rio del Norte in a good place as regards land, water, pasture, and firewood. I gave it as patron saint the glorious apostle of the Indies, San Francisco Xavier, and called and named it the villa of Alburquerque. -- Don Francisco Cuervo y Valdes, April 23, 1706 Resource Guide is available from www.albuquerque300.org Table of Contents 1. Albuquerque Geology 1 Lesson Plans 4 2. First People 22 Lesson Plan 26 3. Founding of Albuquerque 36 Lesson Plans 41 4. Hispanic Life 47 Lesson Plans 54 5. Trade Routes 66 Lesson Plan 69 6. Land Grants 74 Lesson Plans 79 7. Civil War in Albuquerque 92 Lesson Plan 96 8. Coming of the Railroad 101 Lesson Plan 107 9. Education History 111 Lesson Plan 118 10. Legacy of Tuberculosis 121 Lesson Plan 124 11. Place Names in Albuquerque 128 Lesson Plan 134 12. Neighborhoods 139 Lesson Plan 1 145 13. Tapestry of Cultures 156 Lesson Plans 173 14. Architecture 194 Lesson Plans 201 15. History of Sports 211 Lesson Plan 216 16. Route 66 219 Lesson Plans 222 17. Kirtland Air Force Base 238 Lesson Plans 244 18. Sandia National Laboratories 256 Lesson Plan 260 19. Ballooning 269 Lesson Plans 275 My City of Mountains, River and Volcanoes Albuquerque Geology In the dawn of geologic history, about 150 million years ago, violent forces wrenched the earth’s unstable crust. -

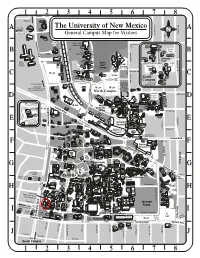

Page 1 a B C D E F G H I J a B C D E F G H I J 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6

12345678 Q Lot to Bldg. 259 277 Girard Blvd. Princeton Dr. to Lands 283 The University of New Mexico A West Lot A 277 N Camino de Salud General Campus Map for Visitors Dr. Vassar 271 265 University Blvd. CNG Bus Only Station Pete & Nancy Domenici Hall Constitution Ave. 341 339 217 260 I Lot Student Yale Blvd. 332 Camino de Salud University Blvd. Family B Casa Stanford Dr. B 333 331 Housing KNME-TV Esperanza 317-329 270 262 337 218 338 Isotopes Park Buena Vista Dr. Carrie 240 243 Tingley 272 North Avenida De Cesar Chavez South Golf Law 301 Lot Hospital 233 241 239 School “The Pit” Zia Course Closed Lot 302 237 236B 230 Mountain Rd. G Lot 312 307 C 223 206 L Lot Stanford Dr. C 242 South 308 238 236A Tucker Rd. Campus 311 Tucker Rd. Domenici to South To Lands West Education Golf Course 311A To Bldg. 259 216 Center C 208 M Lot M Lot 1634 University Blvd. NE C a m Construction a Continuing Education m in Site i o North Campus n o d e d 231 Marble Ave. e S a Yale Blvd. University S l e u D r d 249 D v Psychiatric 246 ic 273 204 o 248 234 266 Services 225 Elks - Recycling 268 Political Archives 228 U M Lot Health 247 n Lomas Blvd. 253 i 226 v Continuing Sciences 229 e T Lot 211 r Education 212 s Center 264 Frontier Ave. i 205 t y 259 201 B l v 258 203 255 d 183 Girard Blvd. -

Water Resources Foundation Report, Bandelier National Monument

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resources Program Center Water Resources Foundation Report Bandelier National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/060 ON THE COVER Photograph: Frijoles Canyon, Bandelier National Monument (Don Weeks - NPS Water Resources Division, 2007) Water Resources Foundation Report Bandelier National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/060 Don Weeks National Park Service Water Resources Division P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 October 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resources Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer- reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. The Natural Resources Technical Reports series is used to disseminate the peer-reviewed results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service’s mission. The reports provide contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. Current examples of such reports include the results of research that addresses natural resource management issues; natural resource inventory and monitoring activities; resource assessment reports; scientific literature reviews; and peer reviewed proceedings of technical workshops, conferences, or symposia. -

UNM Building List

UNM Building List Non- Bldg Assignable Assignable Efficiency Campus Site Name Street City State Zip Year Built Status Gross Sq Ft Usable Sq Ft Sq Ft Sq Ft Ratio Group Albuquerque A0002 - Engineering and Science Computer Pod 201 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1916 OPEN 7,423 6,550 5,762 788 78% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0004 - Elizabeth Waters Center for Dance at Carlisle Gymnasium 301 Yale Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1928 OPEN 37,545 34,805 28,302 6,503 75% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0008 - Bandelier Hall East 401 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1930 OPEN 10,084 8,510 6,276 2,234 62% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0009 - Marron Hall 201 Yale Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1931 OPEN 27,475 19,405 11,577 7,828 42% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0010 - Scholes Hall 1800 Roma Ave. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1936 OPEN 51,160 45,023 32,546 12,477 65% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0011 - Anthropology 500 University Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1937 OPEN 57,668 50,900 40,347 10,553 70% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0012 - Anthropology Annex 301 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1937 OPEN 9,321 8,046 6,033 2,013 65% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0014 - Science and Mathematics Learning Center 311 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 2010 OPEN 74,662 66,271 43,606 22,665 58% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0015 - Hibben Center for Archaeology Research 450 University Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 2001 OPEN 37,922 34,751 26,565 8,186 70% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0016 - Bandelier Hall West 400 University Blvd. -

08-UNM Building List by Site 11-14-12

UNM Building List by Campus, by Building Number revised 11-14-2012 Site Buildin Building Name Building Building Address Year Net Non- Net Useable Gross Building Ownership Campus g Acronym Built Assignable Assignable Square Feet Square Feet Efficiency Map Grid Square Feet Square Feet (GSF) Ratio Coordinate (NASF) A - 0002 ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE COMPUTER POD ESCP 201 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1916 5,762 788 6,550 7,423 78% OWN J-16 ALBUQUERQUE 0004 ELIZABETH WATERS CENTER FOR DANCE AT CARL 301 YALE BLVD. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1928 28,356 6,449 34,805 37,545 76% OWN K-16 CARLISLE GYMNASIUM 0008 BANDELIER HALL EAST BANDE 401 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1930 5,340 3,170 8,510 10,084 53% OWN J-15 0009 MARRON HALL MARN 201 YALE BLVD. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1931 11,406 7,999 19,405 27,475 42% OWN K-17 0010 SCHOLES HALL SCHL 1800 ROMA AVE. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1936 32,810 11,378 44,188 51,160 64% OWN K-14 0011 ANTHROPOLOGY ANTHO 500 UNIVERSITY BLVD. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1937 40,263 10,293 50,556 57,693 70% OWN J-14 0012 ANTHROPOLOGY ANNEX ANTHX 301 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1937 6,042 2,013 8,055 9,321 65% OWN J-16 0014 SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS LEARNING CENTER 311 TERRACE ST. N.E. ALBUQUERQUE, NM 2010 37,981 17,442 55,423 61,840 61% OWN J-15 0015 HIBBEN CENTER FOR ARCHAEOLOGY RESEARCH HIBB 450 UNIVERSITY BLVD. -

Effects of Wildfire and Postfire Floods on Stonefly Detritivores of the Pajarito Plateau, New Mexico

Western North American Naturalist Volume 71 Number 2 Article 13 8-12-2011 Effects of wildfire and postfire floods on stonefly detritivores of the Pajarito Plateau, New Mexico Nicole K. M. Vieira Colorado State University, Fort Collins and Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, Colorado, [email protected] Tiffany R. Barnes Colorado State University, Fort Collins, [email protected] Katharine A. Mitchell Colorado State University, Fort Collins, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Vieira, Nicole K. M.; Barnes, Tiffany R.; and Mitchell, Katharine A. (2011) "Effects of wildfire and postfire floods on stonefly detritivores of the Pajarito Plateau, New Mexico," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 71 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol71/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 71(2), © 2011, pp. 257–270 EFFECTS OF WILDFIRE AND POSTFIRE FLOODS ON STONEFLY DETRITIVORES OF THE PAJARITO PLATEAU, NEW MEXICO Nicole K. M. Vieira1,2,3, Tiffany R. Barnes1, and Katharine A. Mitchell1 ABSTRACT.—Wildfires alter the quantity and quality of allochthonous detritus in streams by burning riparian vegetation and through flushing during postfire floods. As such, fire disturbance may negatively affect detritivorous insects that consume coarse organic matter. -

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement Volume III August 2012 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Albuquerque District Rio Puerco Field Office TABLE OF CONTENTS A CULTURAL RESOURCES ON NON-BLM LANDS LISTED ON THE NRHP ........ A-1 B DESCRIPTION OF GRAZING ALLOTMENTS BY ACREAGE AND AUMS ......... B-1 C EXAMPLES OF PRESCRIBED GRAZING SYSTEMS .............................................. C-1 C.1 Rest-Rotation Grazing ................................................................................................ C-1 C.2 Deferred Rotation Grazing .......................................................................................... C-1 C.3 Deferred Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.4 Alternate Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.5 Short-Duration, High-Intensity Grazing ..................................................................... C-2 D RANGELAND IMPROVEMENTS ............................................................................... D-1 D.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. D-1 D.2 Structural Improvements ............................................................................................. D-1 D.2.1 Fences ..............................................................................................................................