The Relationship of Kung-Fu Movie Viewing to Acculturation Among Chinese-American Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OAKLAND KAJUKENBO KWOON TRAINING MANUAL EDITION 3.0 September 2016

OAKLAND KAJUKENBO KWOON TRAINING MANUAL EDITION 3.0 September 2016 THROUGH THIS FIST WAY, ONE GAINS LONG LIFE AND HAPPINESS OAKLAND KAJUKENBO : MANUAL : EDITION 3.0 catrina marchetti photography © 2015 photography catrina marchetti TABLE OF CONTENTS Family Members, How to use this manual ..........................2 Students, How to use this manual .................................3 School, Teachers, and Lineage .....................................4 History and Philosophy. .7 The Warrior’s Code ...............................................18 The Five Fingers of Self Defense ..................................19 The Oakland Kajukenbo Kwoon Dedication .......................19 Training Practices ................................................20 Kajukenbo Material ..............................................22 Ranking .........................................................39 Questions to think about when preparing for a belt test ...........50 Questions to ask yourself before learning a new form .............52 Glossary .........................................................54 www.oaklandkajukenbo.com 1 OAKLAND KAJUKENBO : MANUAL : EDITION 3.0 HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL FOR OAKLAND KAJUKENBO KWOON ADULT FAMILY MEMBERS This manual has been developed to help the Kajukenbo students in your family to build a strong foundation of self-reflection and self-training. The following are some ideas about how to use the manual: Help Oakland Kajukenbo students to keep track of their copy of the manual and always have it with them when they are at all their Kajukenbo classes and special events. Read through the manual yourself to understand how it is organized and to become familiar with the subject matter. Read through the manual with your family and talk together about the topics it brings up. Share ideas with other families about how to make the training manual easy to find and easy to use. Talk to Sigung and other instructors if you have questions or comments about the manual and the philosophy it reflects. -

Masaaki Hatsumi and Togakure Ryu

How Ninja Conquered the World THE TIMELINE OF SHINOBI POP CULTURE’S WORLDWIDE EXPLOSION Version 1.3 ©Keith J. Rainville, 2020 How did insular Japan’s homegrown hooded set go from local legend to the most marketable character archetype in the world by the mid-1980s? VN connects the dots below, but before diving in, please keep a few things in mind: • This timeline is a ‘warts and all’ look at a massive pop-culture phenomenon — meaning there are good movies and bad, legit masters and total frauds, excellence and exploitation. It ALL has to be recognized to get a complete picture of why the craze caught fire and how it engineered its own glass ceiling. Nothing is being ranked, no one is being endorsed, no one is being attacked. • This is NOT TO SCALE, the space between months and years isn’t literal, it’s a more anecdotal portrait of an evolving phenomenon. • It’s USA-centric, as that’s where VN originates and where I lived the craze myself. And what happened here informed the similar eruptions all over Europe, Latin America etc. Also, this isn’t a history of the Japanese booms that predated ours, that’s someone else’s epic to outline. • Much of what you see spotlighted here has been covered in more depth on VintageNinja.net over the past decade, so check it out... • IF I MISSED SOMETHING, TELL ME! I’ll be updating the timeline from time to time, so if you have a gap to fill or correction to offer drop me a line! Pinholes of the 1960s In Japan, from the 1600s to the 1960s, a series of booms and crazes brought the ninja from shadowy history to popular media. -

Democratic Paralysis and Potential in Post-Umbrella Movement Hong Kong Copyrighted Material of the Chinese University Press | All Rights Reserved Agnes Tam

Hong Kong Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring 2018), 83–99 In Name Only: Democratic Paralysis and Potential in Post-Umbrella Movement Hong Kong Copyrighted Material of The Chinese University Press | All Rights Reserved Agnes Tam Abstract The guiding principle of the 1997 Handover of Hong Kong was stability. The city’s status quo is guaranteed by Article 5 of the Basic Law, which stipulates the continued operation of economic and political systems for fifty years after the transition from British to Chinese sovereignty. Since the Handover, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC) have imposed purposive interpretations on the Basic Law that restrict Hongkongers’ civil participation in local politics. Some official documents of Hong Kong, such as court judgments and public statements, show how the Hong Kong government avails itself to perpetuate such discursive violence through manipulating a linguistic vacuum left by translation issues in legal concepts and their cultural connotations in Chinese and English languages. Twenty years after the Handover, the promise of stability and prosperity in fifty years of unchangedness exists in name only. Highlighting this connection, this article exemplifies the fast-disappearing space for the freedom of expression and for the nominal status quo using the ephemeral appearance of a light installation, Our 60-Second Friendship Begins Now. Embedding the artwork into the skyline of Hong Kong, the artists of this installation adopted the administration’s re-interpretation strategy and articulated their own projection of Hong Kong’s bleak political future through the motif of a count- down device. This article explicates how Hongkongers are compelled to explore alternative spaces to articulate counter-discourses that bring the critical situation of Hong Kong in sight. -

'Christian' Martial Arts

MY LIFE IN “THE WAY” by Gaylene Goodroad 1 My Life in “The Way” RENOUNCING “THE WAY” OF THE EAST “At the time of my conversion, I had also dedicated over 13 years of my life to the martial arts. Through the literal sweat of my brow, I had achieved not one, but two coveted black belts, promoting that year to second degree—Sensei Nidan. I had studied under some internationally recognized karate masters, and had accumulated a room full of trophies while Steve was stationed on the island of Oahu. “I had unwittingly become a teacher of Far Eastern mysticism, which is the source of all karate—despite the American claim to the contrary. I studied well and had been a follower of karate-do: “the way of the empty hand”. I had also taught others the way of karate, including a group of marines stationed at Pearl Harbor. I had led them and others along the same stray path of “spiritual enlightenment,” a destiny devoid of Christ.” ~ Paper Hearts, Author’s Testimony, pg. 13 AUTHOR’S NOTE: In 1992, I renounced both of my black belts, after discovering the sobering truth about my chosen vocation in light of my Christian faith. For the years since, I have grieved over the fact that I was a teacher of “the Way” to many dear souls—including children. Although I can never undo that grievous error, my prayer is that some may heed what I have written here. What you are about to read is a sobering examination of the martial arts— based on years of hands-on experience and training in karate-do—and an earnest study of the Scriptures. -

Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century

Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wong, John. 2012. Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9282867 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 – John D. Wong All rights reserved. Professor Michael Szonyi John D. Wong Global Positioning: Houqua and his China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century Abstract This study unearths the lost world of early-nineteenth-century Canton. Known today as Guangzhou, this Chinese city witnessed the economic dynamism of global commerce until the demise of the Canton System in 1842. Records of its commercial vitality and global interactions faded only because we have allowed our image of old Canton to be clouded by China’s weakness beginning in the mid-1800s. By reviving this story of economic vibrancy, I restore the historical contingency at the juncture at which global commercial equilibrium unraveled with the collapse of the Canton system, and reshape our understanding of China’s subsequent economic experience. I explore this story of the China trade that helped shape the modern world through the lens of a single prominent merchant house and its leading figure, Wu Bingjian, known to the West by his trading name of Houqua. -

Nickelodeon Masters the Elements with the Legend of Korra

For Immediate Release NICKELODEON MASTERS THE ELEMENTS WITH THE LEGEND OF KORRA London, UK – 29th April, 2013 – From the creators of the Hit Series Avatar: The Last Airbender, The Legend of Korra is set to premiere on Nickelodeon on Sunday, 7th July at 9:00am. The mythology from the critically acclaimed Avatar series continues in the new animation which follows a new Avatar named Korra, a 17-year-old headstrong and rebellious girl who continually challenges tradition on her quest to become a fully realized Avatar. New episodes of The Legend of Korra will premiere each Sunday at 9:00am. The Legend of Korra takes place 70 years after the events of Avatar: The Last Airbender and follows the next Avatar after Aang – a girl named Korra (Janet Varney) who is from the Southern Water Tribe. With three of the four elements under her belt (Earth, Water and Fire), Korra seeks to master Air. Her quest leads her to Republic City, the modern “Avatar” world that is a virtual melting pot where individuals from all nations live and thrive. Korra quickly discovers that the metropolis is plagued by crime as well as a revolution that threatens to rip the city apart. Under the tutelage of Aang’s son, Tenzin (J.K. Simmons), Korra begins her airbending training while dealing with the dangers at large. In the premiere episode, “Welcome to Republic City,” Korra leaves the safety of her home and travels to bustling Republic City to begin her airbending training. Once there, she is shocked to find a big city full of dangers. -

Recommended Reading

RECOMMENDED READING The following books are highly recommended as supplements to this manual. They have been selected on the basis of content, and the ability to convey some of the color and drama of the Chinese martial arts heritage. THE ART OF WAR by Sun Tzu, translated by Thomas Cleary. A classical manual of Chinese military strategy, expounding principles that are often as applicable to individual martial artists as they are to armies. You may also enjoy Thomas Cleary's "Mastering The Art Of War," a companion volume featuring the works of Zhuge Liang, a brilliant strategist of the Three Kingdoms Period (see above). CHINA. 9th Edition. Lonely Planet Publications. Comprehensive guide. ISBN 1740596870 CHINA, A CULTURAL HISTORY by Arthur Cotterell. A highly readable history of China, in a single volume. THE CHINA STUDY by T. Colin Campbell,PhD. The most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted. ISBN 1-932100-38-5 CHINESE BOXING: MASTERS AND METHODS by Robert W. Smith. A collection of colorful anecdotes about Chinese martial artists in Taiwan. Kodansha International Ltd., Publisher. ISBN 0-87011-212-0 CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS TRAINING MANUALS (A Historical Survey) by Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo CHRONICLES OF TAO, THE SECRET LIFE OF A TAOIST MASTER by Deng Ming-Dao. Harper San Francisco, Publisher ISBN 0-06-250219-0 (Note: This is an abridged version of a three- volume set: THE WANDERING TAOIST (Book I), SEVEN BAMBOO TABLETS OF THE CLOUDY SATCHEL (Book II), and GATEWAY TO A VAST WORLD (Book III)) CLASSICAL PA KUA CHANG FIGHTING SYSTEMS AND WEAPONS by Jerry Alan Johnson and Joseph Crandall. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Hit Cartoon: Avatar: the Last Airbender

Bowens 1 Emily Bowens ([email protected]) Dr. O’Donnell Engl. 3130 12/2/20 More Than a Kid’s Show: A Review of Nickelodeon’s Hit Cartoon: Avatar: The Last Airbender Gene, Yang Avatar: The Last Airbender - The Promise Part 1 Cover) Fifteen years after its original air date, Avatar: The Last Airbender has succeeded in becoming ingrained in pop culture with a recent revival just earlier this year. Put your misjudgments about kid’s shows aside and become captivated by a powerful and mesmerizing story about war, violence, and the power of redemption. Bowens 2 A Reintroduction Show Title: Avatar: The Last At a time when all seemed wrong with the world, and anxiety was Airbender setting in after being in lockdown for two months in a Covid-ridden world, a Premiere Date: February 21, 2005 End Date: July,19 2008 guardian angel in the form of Netflix released the news that its streaming Rating: TV-7 service would be releasing Nickelodeon’s Avatar: The Last Airbender on Genre: Animation, Adventure, and May, 15 2020. So my boyfriend and I prepared to binge watch one of the Action most important shows from our childhood to bring back memories and cure Episodes: 61 our quarantine boredom. You may be wondering to yourself, why would Seasons: 3 you guys be so excited about a kid’s show that premiered fifteen years ago? Total Airtime: 1464 minutes You see, Avatar: The Last Airbender is a show that you can keep watching Creators: Michael Dante over and over again and keep finding new meaning every time. -

Martial Arts As Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World

1 Introduction Martial Arts, Transnationalism, and Embodied Knowledge D. S. Farrer and John Whalen-Bridge The outlines of a newly emerging field—martial arts studies—appear in the essays collected here in Martial Arts as Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World. Considering knowledge as “embodied,” where “embodiment is an existential condition in which the body is the subjective source or intersubjective ground of experience,” means under- standing martial arts through cultural and historical experience; these are forms of knowledge characterized as “being-in-the-world” as opposed to abstract conceptions that are somehow supposedly transcendental (Csor- das 1999: 143). Embodiment is understood both as an ineluctable fact of martial training, and as a methodological cue. Assuming at all times that embodied practices are forms of knowledge, the writers of the essays presented in this volume approach diverse cultures through practices that may appear in the West to be esoteric and marginal, if not even dubious and dangerous expressions of those cultures. The body is a chief starting point for each of the enquiries collected in this volume, but embodiment, connecting as it does to imaginative fantasy, psychological patterning, and social organization, extends “far beyond the skin of the practicing individual” (Turner and Yangwen 2009). The discourse of martial arts, which is composed of the sum total of all the ways in which we can register, record, and otherwise signify the experience of martial arts mind- 1 © 2011 State -

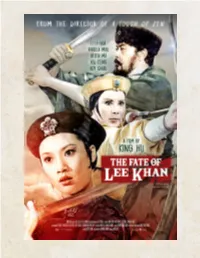

The-Fate-Of-Lee-Khan Presskit.Pdf

presents NEW 2K DIGITAL RESTORATION Hong Kong & Taiwan / 1973 / Action / Mandarin with English Subtitles 106 minutes / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Sound U.S. THEATRICAL PREMIERE Opening April 5th in New York at Metrograph Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Michael Lieberman | Metrograph | (212) 660-0312 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (201) 736-0261 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS In his follow-up to the critically acclaimed A TOUCH OF ZEN, trailblazing filmmaker King Hu brings together an all-star female cast, including Hong Kong cinema stalwart Li Li-hua and Angela “Lady Kung Fu” Mao, in this lively martial arts adventure. When Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army, resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. Featuring stunning action sequences choreographed by Jackie Chan’s “Kung Fu elder brother” Sammo Hung and a generous mix of intrigue and humor, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is a legendary wuxia masterpiece. SHORT SYNOPSIS Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army. Resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. LOGLINE King Hu's legendary wuxia masterpiece, starring Li Li-hua, Angela Mao and Hsu Feng. SELECT PRESS “The Fate of Lee Khan is to the Chinese martial arts movie what Once Upon a Time in the West is to the Italian Western: a brilliant anthology of its genre's theme and styles, yielding an exhilaratingly original vision.” –Time Out “The Fate of Lee Khan is a masterclass in getting the maximum from every aspect of production. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth.