Jacqueline's Visit to the WW1 Battlefields of France and Flanders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simcoe School War Memorial Stone

Simcoe School War Memorial Stone Overview The City of London Culture Office has been informed of a memorial stone that commemorates London soldiers that died during the First World War. Due to the nature of the memorial’s history, its location, ownership, and responsibility for its care are of concern to those that have brought this matter forward. Memorials are covered under the City of London’s definition of public art.1 This report will provide an overview of the Simcoe School War Memorial’s history, design, and significance, to assist in the resolution of this matter. History In 1887, Governor Simcoe School (later re-named Simcoe Street School) was built on the site of the last remaining log-house in London.2 See Figure 1 for a photograph of the original school building. This school was attended by a few notable Londoners, including Guy Lombardo, a famous Canadian violinist and the bandleader of The Royal Canadians. During the First World War, a number of past students from the Simcoe Street School volunteered for overseas duty for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Figure 1. Photograph of Simcoe Street School, also known as Governor Simcoe School. Source: “Simcoe Street School, London, Ontario,” Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario, http://images.ourontario.ca/london/74863/data. After the war, many public schools in London felt the need to commemorate their former students that had died while serving overseas. Throughout the 1920s, schools across London commissioned the creation of memorial plaques and honour rolls. For example, honour rolls Simcoe School War Memorial Stone – Research Report 2 were commissioned for Wortley Road School, the former Empress Public School and Talbot Street School, Central Secondary School, Tecumseh Public School, South Secondary School, and Lorne Avenue Public School. -

A Brief History of War Memorial Design

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN war memorial may take many forms, though for most people the first thing that comes to mind is probably a freestanding monument, whether more sculptural (such as a human figure) or architectural (such as an arch or obelisk). AOther likely possibilities include buildings (functional—such as a community hall or even a hockey rink—or symbolic), institutions (such as a hospital or endowed nursing position), fountains or gardens. Today, in the 21st century West, we usually think of a war memorial as intended primarily to commemorate the sacrifice and memorialize the names of individuals who went to war (most often as combatants, but also as medical or other personnel), and particularly those who were injured or killed. We generally expect these memorials to include a list or lists of names, and the conflicts in which those remembered were involved—perhaps even individual battle sites. This is a comparatively modern phenomenon, however; the ancestors of this type of memorial were designed most often to celebrate a victory, and made no mention of individual sacrifice. Particularly recent is the notion that the names of the rank and file, and not just officers, should be set down for remembrance. A Brief History of War Memorial Design 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Ancient Precedents The war memorials familiar at first hand to Canadians are most likely those erected in the years after the end of the First World War. Their most well‐known distant ancestors came from ancient Rome, and many (though by no means all) 20th‐century monuments derive their basic forms from those of the ancient world. -

On the Trail of the Newfoundland Caribou

On the Trail of the Newfoundland Caribou Patriotic Tour 2016 France & Belgium In Conjunction with the Churches of Newfoundland and Labrador June 26 - July 5, 2016 • 10 Days • 16 Meals Escorted by Rt. Rev. Dr. Geoff Peddle Anglican Bishop of the Diocese of Eastern Newfoundland and Labrador Caribou Monument at Beaumont Hamel A NEWFOUNDLAND PILGRIMAGE ON THE TRAIL OF THE CARIBOU The years 2014-2018 mark the 100th anniversaries of the First World War. We must never forget the tremendous contributions and horrendous sacrifices that so many Newfoundlanders and Labradorians made to that cause. Fighting in the uniforms of both the Navy and the Army, in the Merchant Marine and the Forestry Corps, our brave forebears never hesitated to stand in harm’s way to protect our homes, our families and our values. While many of them paid the supreme sacrifice, many more came home wounded in body and/or mind. We must also never forget the suffering at home of a generation for whom the effects of that war would be felt for the rest of their lives. The pastoral guidance was provided by many Newfoundland Padres who served the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, including Padre Tom Nangle who went on to become Newfoundland’s representative on the Imperial War Graves Commission. His vision brought the “Trail of the Caribou” to reality, and is the touchstone for many of those who wish to stand “where once they stood.” Knowing that many of those brave soldiers were members of our Newfoundland Churches, we have vowed to mark this important anniversary by a spiritual pilgrimage, to the battlefields of Europe in the summer of 2016. -

The Gate of Eternal Memories: Architecture Art and Remembrance

CONTESTED TERRAINS SAHANZ PERTH 2006 JOHN STEPHENS THE GATE OF ETERNAL MEMORIES: ARCHITECTURE ART AND REMEMBRANCE. John Richard Stephens Faculty of Built Environment Art and Design, Curtin University of Technology, Perth Western Australia, Australia. ABSTRACT The Menin Gate is a large memorial in Belgium to British Empire troops killed and missing during the battles of the Ypres Salient during the First World War. Designed by the architect Reginald Blomfield in 1922 it commemorates the 56,000 soldiers whose bodies were never found including 6,160 Australians. Blomfield’s sobering memorial has symbolic architectural meaning, and signifi- cance and commemorative meaning to relatives of those whose names appeared on the sur- faces of the structure. In 1927 the Australian artist and soldier William Longstaff painted his alle- gorical painting “Menin gate at Midnight showing the Gate as an ethereal structure in a brood- ing landscape populated with countless ghostly soldiers. The painting was an instant success and was reverentially exhibited at all Australian capital cities. From the contested terrain of war re- membrance this paper will argue that both the Gate and its representation in “Menin Gate at Midnight” are linked through the commemorative associations that each employ and have in common. “Here was the world’s worst wound. And Imperial War Graves cemetery. As a product of here with pride particular political and ethical policies, the bodies ‘Their name liveth for evermore’ the of British Empire soldiers were not returned to their Gateway claims. countries but buried close to where they met their Was ever an immolation so belied As these intolerably nameless names? fate. -

Grimes, Ronald

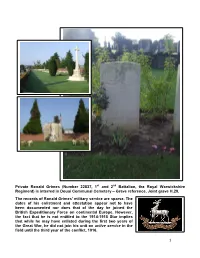

Private Ronald Grimes (Number 22837, 1st and 2nd Battalion, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment) is interred in Douai Communal Cemetery – Grave reference, Joint grave H.29. The records of Ronald Grimes’ military service are sparse. The dates of his enlistment and attestation appear not to have been documented nor does that of the day he joined the British Expeditionary Force on continental Europe. However, the fact that he is not entitled to the 1914-1915 Star implies that while he may have enlisted during the first two years of the Great War, he did not join his unit on active service in the field until the third year of the conflict, 1916. 1 Furthermore, the recorded (in places) service of Private Grimes with both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Warwicks leads one to believe that this was also the order in which he was attached to them. *However, there appears to be little further evidence of Private Grimes serving with the 2nd Battalion of the Regiment. The Forces War Records web-site has him with the 1st. Both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Royal Warwickshire had been ordered to the Continent in 1914. The 1st Battalion had fought in the Retreat from Mons and then in the Race to the Sea, the campaign which ensured the static nature of the Great War for the next few years. It had been stationed in Belgium at the time of the Second Battle of Ypres, then in northern France until 1916 when the British assumed responsibility for the area of the Somme from the French. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

31Th March 2019 Hotspots

31TH MARCH 2019 HOTSPOTS 7 RACES IN FLANDERS FIELDS KM 85 KM 65 FURNES DIKSMUIDE START KORTEMARK TIELT DEINZE ROESBRUGGE-HARINGE KM 233 WAREGEM KM POPERINGE YPRES ZONNEBEKE 255 COURTRAI WEVELGEM HEUVELLAND MENIN ARRIVAL MESSINES COMINES-WARNETON PLOEGSTEERT KM 193 The map describes a limited number of hotspots. West-Flanders has 1,388 war remnants. This means that you can discover many other relics along the track, such as Locre No. 10 Cemetery, La Clytte Military Cemetery, Wulverghem-Lindenhoek Road Military Cemetery … the latter two provide a final resting place for more than 1,000 soldiers each. The ‘km’ marker indicates the distance to each hotspot from the starting position. - If the hotspot is located on the track (marked with ), then the kilometre marker indicates the track distance. - If the hotspot described is not located along the track, then the distance indicated will denote the distance from the starting point to the nearest kilometer marker on the track. These hotspots are located no further than 6.5 km from the track as the crow flies (men’s and ladies’ track combined). - For example, the Pool of Peace is not labelled with and is therefore a hotspot not on the track but nearby. This means that the hotspot is situated within a range of 6.5 km from the track. Specifically: the Pool of Peace is 1.75 km from the trail, on the road from Kemmel to Messines, at 164 km into the race. The ‘Commonwealth War Graves Commission’ (CWGC) is responsible for commemorating almost 1 700 000 British Com- monwealth soldiers who lost their lives in one of the two World Wars. -

Cannock Chase War Cemetery

OUR WAR GRAVES YOUR HISTORY Cannock Chase War Cemetery Points of interest… Commemorations: 379 First World War: 97 Commonwealth, 286 German Second World War: 3 Commonwealth, 25 German In the autumn of 1914, the British Army began constructing camps at Brocton Casualties from the following and Rugeley on Cannock Chase. Housing up to 40,000 men at any one time, the nations camps were used first as transit camps for soldiers heading to the Western Front. Cannock Chase subsequently became a training facility for various Commonwealth Germany units, and as many as 500,000 troops were trained here during the First World Poland War. New Zealand UK A hospital serving both Brocton and Rugeley camps was established at Brindley Heath in 1916. The hospital had a total of 1,000 beds as well as housing convalescing soldiers from the Western Front. The cemetery was created in 1917 Things to look out for… to serve as the final resting place for men who died while being treated in the hospital. The majority of the Commonwealth burials are New Zealanders, many of Boy soldier – Albert Urell of whom died in the flu pandemic that broke out toward the end of the war. the Royal Garrison Artillery Aircraftman 1st Class, In April 1917, part of the camp at Brocton was turned into a prisoner of war George Edgar Hicks who was camp and hospital for captured German soldiers and the cemetery was also used run over and killed by a bus on for German burials. Sandon Road Stafford, in the blackout. A coroner’s verdict of accidental death was recorded. -

A Monumental Past

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN Faculty of Arts Institute for Cultural Studies A MONUMENTAL PAST AN EXPLORATION OF THE RELATION BETWEEN THE ENDURING POPULARITY OF THE MENIN GATE AND THE COMMEMORATION OF WORLD WAR ONE IN BRITAIN Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Cultural Studies Advisor by M. Bl eyen Myrthel Van Etterbeeck 2011-2012 ABSTRACT Wereldoorlog I gaf in Groot Brittannië aanleiding tot een groots herinneringsproject. Door een proces van selectie, articulatie, herhaling en weglating creëerde de Britten een gezuiverde herinnering aan het moeilijke verleden van de oorlog dat hen kon helpen bij het verwerken van verdriet en het eren en herdenken van de doden. Het Britse monument de Menenpoort, nabij het centrum van Ieper, is voortgekomen uit dit project en is gewijd aan de Britse soldaten die vermist raakten in de drie slagen bij Ieper. Sinds de oprichting, in 1927, komen mensen er samen om de gevallenen van de oorlog te herdenken. In zijn vijfentachtig jarige bestaan heeft het miljoenen bezoekers ontvangen en de laatste 30 jaar is het enkel in populariteit toegenomen. Deze thesis onderzoekt de relatie tussen de voortdurende populariteit van de Menenpoort en de Britse herdenking van, en herinneringen aan de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Daarbij word gebruik gemaakt van het theoretische kader van ‘memory studies’ met name de typologie van Aleida Assmann. Zij definieert sociale herinneringen als een vorm van herinneren die zich ontwikkelt tussen en gedeeld wordt door verschillende mensen maar gefundeerd blijft in geleefde ervaring. Deze vorm van herinneren kan een hele natie of generatie omspannen maar verdwijnt met zijn dragers. -

Dumfries and Galloway War Memorials

Annandale and Eskdale War Memorials Annan Memorial High Street, Annan Dumfries and Galloway DG12 6AJ Square base surmounted by pedestal and Highland Soldier standing at ease with rifle. Applegarth and Sibbaldbie Parishoners Memorial Applegarth Church Applegarth Dumfries and Galloway DG11 1SX Sandstone. Two stepped square base surmounted by two stepped plinth, tapering shaft and Latin cross. Brydekirk Memorial Brydekirk Parish Church Brydekirk Dumfries and Galloway DG12 5ND Two stepped base surmounted by square pedestal and small cross. Surrounded by wrought iron railings. Canonbie Memorial B7201 Canonbie Dumfries & Galloway DG14 0UX Tapered base surmounted by pedestal and figure of a serviceman with head bowed, rifle over shoulder. Cummertrees Memorial Cummertrees Parish Church Cummertrees Dumfries & Galloway DG1 4NP Wooden lych-gate with tiled roof mounted onto a stone base. Inscription over entrance. Dalton Memorial Dalton Parish Church Dalton Dumfries & Galloway DG11 1DS Tapered square plinth surmounted by tapered shaft and Celtic cross. Dornock Memorial B721 Eastriggs Dumfries & Galloway DG12 6SY White marble. Three stepped base surmounted by double plinth, tapering pedestal and column which narrows at the top. Ecclefechan, Hoddom Memorial Ecclefechan Dumfries & Galloway DG11 3BY Granite. Tapered stone base surmounted by two stepped granite base, pedestal and obelisk. Surrounded by wrought iron railings. Eskdalemuir Memorial Eskdalemuir Parish Church B709 Eskdalemuir Dumfries & Galloway DG13 0QH Three stepped square stone base surmounted by rough hewn stone pedestal and tapered top. Ewes Memorial Ewes Parish Church A7 Ewes Langholm Dumfries & Galloway DG13 0HJ White marble. Square base surmounted by plinth and Latin cross mounted on a rough hewn base. Gretna Green Memorial Gretna Green Dumfries & Galloway DG16 5DU Granite. -

Guide Des Sources Sur La Première Guerre Mondiale Aux A.D

GUIDE DES SOURCES SUR LA PREMIERE GUERRE MONDIALE AUX ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES DE LA SOMME ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES DE LA SOMME AMIENS — OCTOBRE 2015 Illustration de couverture : carte de correspondance militaire (détail), cote 99 R 330935. Date de dernière mise à jour du guide : 13 octobre 2015. 2 Table des matières abrégée Une table des matières détaillée figure à la fin du guide. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 5 GUIDE........................................................................................................................................ 10 K - LOIS, ORDONNANCES, ARRETES ................................................................................................ 12 3 K - Recueil des actes administratifs de la préfecture de la Somme (impr.) .................................... 12 4 K - Arrêtés du préfet (registres)....................................................................................................... 12 M - ADMINISTRATION GENERALE ET ECONOMIE ........................................................................... 13 1 M - Administration generale du département.................................................................................. 13 2 M - Personnel de la préfecture, sous-préfectures et services annexes.......................................... 25 3 M - Plébisistes et élections............................................................................................................. -

Monuments As Symbol

Monuments St John’s NFD Beaumont-Hamel • 1 July 1916, first day of the Somme offensive – British suffer 57,470 casualties • 1st Newfoundland Regiment virtually annihilated: – lost 700 men trying to advance over 500m of open ground St Johns NFD 1 July in Newfoundland • The anniversary of the Beaumont-Hamel slaughter • Canada Day • Conflicting memories Monuments • Landscape symbols • Sites of memory • Make claims about history – What and how to remember • Monument must endure changes in meaning Monuments and Power • Monuments help to project cultural power? Monuments and Memory • Monuments attempt to – Promote a way of looking, thinking – Promote a public memory • But culture, politics change – Monuments of one era may become embarrassing to the next WWI War Memorials • Landscape elements • Allied ones tend to be grand in scale, dominating • Mostly built in the 1920s • Become places of official memory Lutyens: Thiepval cenotaph WWI War Memorials • May sanitise war – noble sacrifice remembered, brutal horror forgotten – Confer purpose and meaning on often senseless slaughter Fred Varley 1918 • For What? WWI War Memorials • Product of official culture: – selected architects, sculptors, artists – officially-sanctioned symbols • cross of sacrifice • sorrowing angels Vimy Memorial • Designed by Walter Allward – Sorrowing angels, mothers, fathers Vimy unveiled 1936 Monuments and Monuments • Grand schemes for monuments displaced earlier attempts to erect monuments • Even at Vimy Ridge Canada’s National Cenotaph • Peace tower intended as a war memorial • Temporary cenotaphs on Parliamentary steps • National Cenotaph unveiled by King George VI in 1939 1946 Vancouver • Unveiled April 1924 London UK • National cenotaph • Designed by Lutyens Commonwealth War-Graves Commission • Began building WW1 cemeteries in 1919 • Each has: – Standardized grave stones – Sir Reginald Bloomfield’s Cross of Sacrifice (in 3 sizes) – Lutyen’s altar-like stone of remembrance Their name liveth ..