An Introduction to Objective Caml

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lisp: Final Thoughts

20 Lisp: Final Thoughts Both Lisp and Prolog are based on formal mathematical models of computation: Prolog on logic and theorem proving, Lisp on the theory of recursive functions. This sets these languages apart from more traditional languages whose architecture is just an abstraction across the architecture of the underlying computing (von Neumann) hardware. By deriving their syntax and semantics from mathematical notations, Lisp and Prolog inherit both expressive power and clarity. Although Prolog, the newer of the two languages, has remained close to its theoretical roots, Lisp has been extended until it is no longer a purely functional programming language. The primary culprit for this diaspora was the Lisp community itself. The pure lisp core of the language is primarily an assembly language for building more complex data structures and search algorithms. Thus it was natural that each group of researchers or developers would “assemble” the Lisp environment that best suited their needs. After several decades of this the various dialects of Lisp were basically incompatible. The 1980s saw the desire to replace these multiple dialects with a core Common Lisp, which also included an object system, CLOS. Common Lisp is the Lisp language used in Part III. But the primary power of Lisp is the fact, as pointed out many times in Part III, that the data and commands of this language have a uniform structure. This supports the building of what we call meta-interpreters, or similarly, the use of meta-linguistic abstraction. This, simply put, is the ability of the program designer to build interpreters within Lisp (or Prolog) to interpret other suitably designed structures in the language. -

Drscheme: a Pedagogic Programming Environment for Scheme

DrScheme A Pedagogic Programming Environment for Scheme Rob ert Bruce Findler Cormac Flanagan Matthew Flatt Shriram Krishnamurthi and Matthias Felleisen Department of Computer Science Rice University Houston Texas Abstract Teaching intro ductory computing courses with Scheme el evates the intellectual level of the course and thus makes the sub ject more app ealing to students with scientic interests Unfortunatelythe p o or quality of the available programming environments negates many of the p edagogic advantages Toovercome this problem wehavedevel op ed DrScheme a comprehensive programming environmentforScheme It fully integrates a graphicsenriched editor a multilingua l parser that can pro cess a hierarchyofsyntactically restrictivevariants of Scheme a functional readevalprint lo op and an algebraical ly sensible printer The environment catches the typical syntactic mistakes of b eginners and pinp oints the exact source lo cation of runtime exceptions DrScheme also provides an algebraic stepp er a syntax checker and a static debugger The rst reduces Scheme programs including programs with assignment and control eects to values and eects The to ol is useful for explainin g the semantics of linguistic facilities and for studying the b ehavior of small programs The syntax c hecker annotates programs with fontandcolorchanges based on the syntactic structure of the pro gram It also draws arrows on demand that p oint from b ound to binding o ccurrences of identiers The static debugger roughly sp eaking pro vides a typ e inference system -

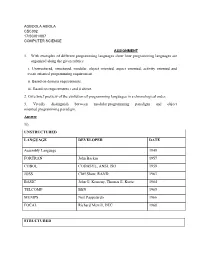

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Programming Language Use in US Academia and Industry

Informatics in Education, 2015, Vol. 14, No. 2, 143–160 143 © 2015 Vilnius University DOI: 10.15388/infedu.2015.09 Programming Language Use in US Academia and Industry Latifa BEN ARFA RABAI1, Barry COHEN2, Ali MILI2 1 Institut Superieur de Gestion, Bardo, 2000, Tunisia 2 CCS, NJIT, Newark NJ 07102-1982 USA e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received: July 2014 Abstract. In the same way that natural languages influence and shape the way we think, program- ming languages have a profound impact on the way a programmer analyzes a problem and formu- lates its solution in the form of a program. To the extent that a first programming course is likely to determine the student’s approach to program design, program analysis, and programming meth- odology, the choice of the programming language used in the first programming course is likely to be very important. In this paper, we report on a recent survey we conducted on programming language use in US academic institutions, and discuss the significance of our data by comparison with programming language use in industry. Keywords: programming language use, academic institution, academic trends, programming lan- guage evolution, programming language adoption. 1. Introduction: Programming Language Adoption The process by which organizations and individuals adopt technology trends is complex, as it involves many diverse factors; it is also paradoxical and counter-intuitive, hence difficult to model (Clements, 2006; Warren, 2006; John C, 2006; Leo and Rabkin, 2013; Geoffrey, 2002; Geoffrey, 2002a; Yi, Li and Mili, 2007; Stephen, 2006). This general observation applies to programming languages in particular, where many carefully de- signed languages that have superior technical attributes fail to be widely adopted, while languages that start with modest ambitions and limited scope go on to be widely used in industry and in academia. -

Categorical Variable Consolidation Tables

CATEGORICAL VARIABLE CONSOLIDATION TABLES FlossMole Data Name Old number of codes New number of codes Table 1: Intended Audience 19 5 Table 2: FOSS Licenses 60 7 Table 3: Operating Systems 59 8 Table 4: Programming languages 73 8 Table 5: SF Project topics 243 19 Table 6: Project user interfaces 48 9 Table 7 DB Environment 33 3 Totals 535 59 Table 1: Intended Audience: Consolidated from 19 to 4 categories Rationale for this consolidation: Categories that had similar characteristics were grouped together. For example, Customer Service, Financial and Insurance, Healthcare Industry, Legal Industry, Manufacturing, Telecommunications Industry, Quality Engineers and Aerospace were grouped together under the new category “Business.” End Users/Desktop and Advanced End Users were grouped together under the new category “End Users.” Developers, Information Technology and System Administrators were grouped together under the new category “Computer Professionals.” Education, Religion, Science/Research and Other Audience were grouped under the new category “Other.” Categories containing large numbers of projects were generally left as individual categories. Perhaps Religion and Education should have be left as separate categories because of they contain a relatively large number of projects. Since Mike recommended we get the number of categories down to 50, I consolidated them into the “Other” category. What was done: I created a new table in sf merged called ‘categ_intend_aud_aug06’. This table is a duplicate of the ‘project_intended_audience01_aug_06’ table with the fields ‘new_code’ and ‘new_description’ added. I updated the new fields in the new table with the new codes and descriptions listed in the table below using a python script I (Bob English) wrote called add_categ_intend_aud.py. -

From Krivine's Machine to the Caml Implementations

From Krivine's machine to the Caml implementations Xavier Leroy INRIA Rocquencourt 1 In this talk An illustration of the strengths and limitations of abstract machines for the purpose of e±cient execution of strict functional languages (Caml). 1. A retrospective on the ZAM, a call-by-value variant of Krivine's machine. 2. From abstract machines to e±cient P.L. implementations: the example of Caml Light and Objective Caml. 3. Beyond abstract machines: push-enter models vs. eval-apply models. 2 Why are abstract machines interesting? On the theory side (λ-calculus, semantics): Abstract machines expose concepts lacking or implicit in the λ-calculus: • Reduction strategy, evaluation order. • Data representations, esp. closures and environments. On the implementation side: Compilation to abstract machine code o®ers much better performance than interpreters. Abstract machine code as an intermediate language for machine-code generation. Abstract machine code as an architecture-independent low-level format for distributing compiled programs (JVM, .Net). 3 There are better ways In every area where abstract machines help, there are arguably better alternatives: • Exposing reduction order: CPS transformation, structured operational semantics, reduction contexts. • Closures and environments: explicit substitutions. • E±cient execution: optimizing compilation to real machine code. • Intermediate languages: RTL, SSA, CPS, A-normal forms, etc. • Code distribution: ANDF (?). Abstract machines do many things well but none very well. This we will illustrate in the case of e±cient execution of Caml. 4 A retrospective on the ZAM 5 The starting point The Caml language and implementation circa 1989: • Core ML (CBV λ-calculus) with primitives, data types and pattern-matching. -

The Definition of Standard ML, Revised

The Definition of Standard ML The Definition of Standard ML (Revised) Robin Milner, Mads Tofte, Robert Harper and David MacQueen The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England c 1997 Robin Milner All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The definition of standard ML: revised / Robin Milner ::: et al. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-63181-4 (alk. paper) 1. ML (Computer program language) I. Milner, R. (Robin), 1934- QA76.73.M6D44 1997 005:1303|dc21 97-59 CIP Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Syntax of the Core 3 2.1 Reserved Words . 3 2.2 Special constants . 3 2.3 Comments . 4 2.4 Identifiers . 5 2.5 Lexical analysis . 6 2.6 Infixed operators . 6 2.7 Derived Forms . 7 2.8 Grammar . 7 2.9 Syntactic Restrictions . 9 3 Syntax of Modules 12 3.1 Reserved Words . 12 3.2 Identifiers . 12 3.3 Infixed operators . 12 3.4 Grammar for Modules . 13 3.5 Syntactic Restrictions . 13 4 Static Semantics for the Core 16 4.1 Simple Objects . 16 4.2 Compound Objects . 17 4.3 Projection, Injection and Modification . 17 4.4 Types and Type functions . 19 4.5 Type Schemes . 19 4.6 Scope of Explicit Type Variables . 20 4.7 Non-expansive Expressions . 21 4.8 Closure . -

Comparative Programming Languages CM20253

We have briefly covered many aspects of language design And there are many more factors we could talk about in making choices of language The End There are many languages out there, both general purpose and specialist And there are many more factors we could talk about in making choices of language The End There are many languages out there, both general purpose and specialist We have briefly covered many aspects of language design The End There are many languages out there, both general purpose and specialist We have briefly covered many aspects of language design And there are many more factors we could talk about in making choices of language Often a single project can use several languages, each suited to its part of the project And then the interopability of languages becomes important For example, can you easily join together code written in Java and C? The End Or languages And then the interopability of languages becomes important For example, can you easily join together code written in Java and C? The End Or languages Often a single project can use several languages, each suited to its part of the project For example, can you easily join together code written in Java and C? The End Or languages Often a single project can use several languages, each suited to its part of the project And then the interopability of languages becomes important The End Or languages Often a single project can use several languages, each suited to its part of the project And then the interopability of languages becomes important For example, can you easily -

A Simple and Efficient Compiler for a Minimal Functional Language

MinCaml: A Simple and Efficient Compiler for a Minimal Functional Language ∗ Eijiro Sumii Tohoku University [email protected] Abstract who learn ML, but they often think “I will not use it since I do We present a simple compiler, consisting of only 2000 lines of ML, not understand how it works.” Or, even worse, many of them make for a strict, impure, monomorphic, and higher-order functional lan- incorrect assumptions based on arbitrary misunderstanding about guage. Although this language is minimal, our compiler generates implementation methods. To give a few real examples: as fast code as standard compilers like Objective Caml and GCC • “Higher-order functions can be implemented only by inter- for several applications including ray tracing, written in the opti- preters” (reason: they do not know function closures). mal style of each language implementation. Our primary purpose is education at undergraduate level to convince students—as well • “Garbage collection is possible only in byte code” (reason: they as average programmers—that functional languages are simple and only know Java and its virtual machine). efficient. • “Functional programs consume memory because they cannot reuse variables, and therefore require garbage collection” (rea- Categories and Subject Descriptors D.3.4 [Programming Lan- son: ???). guages]: Processors—Compilers; D.3.2 [Programming Languages]: Language Classifications—Applicative (functional) languages Obviously, these statements must be corrected, in particular when they are uttered from the mouths of our students. General Terms Languages, Design But how? It does not suffice to give short lessons like “higher- Keywords ML, Objective Caml, Education, Teaching order functions are implemented by closures,” because they often lead to another myth such as “ML functions are inefficient because they are implemented by closures.” (In fact, thanks to known func- 1. -

A Modular Module System

To appear in J. Functional Programming 1 A modular module system XAVIER LEROY INRIA Rocquencourt B.P. 105, 78153 Le Chesnay, France [email protected] Abstract A simple implementation of an SML-like module system is presented as a module param- eterized by a base language and its type-checker. This implementation is useful both as a detailed tutorial on the Harper-Lillibridge-Leroy module system and its implementation, and as a constructive demonstration of the applicability of that module system to a wide range of programming languages. 1 Introduction Modular programming can be done in any language, with su±cient discipline from the programmers (Parnas, 1972). However, it is facilitated if the programming lan- guage provides constructs to express some aspects of the modular structure and check them automatically: implementations and interfaces in Modula, clusters in CLU, packages in Ada, structures and functors in ML, classes in C++ and Java, . Even though modular programming has little to do with the particulars of any programming language, each of the languages above puts forward its own design of a module system, without reusing directly an earlier module system | as if the design of a module system were so dependent on the base language that transferring a module system from one language to another were impossible. Consider for instance the module system of SML (MacQueen, 1986; Milner et al., 1997), also used in Objective Caml (Leroy et al., 1996). This is one of the most powerful module systems proposed so far, particularly for its treatment of parameterized modules as functors, i.e. -

An Interpreter for Vaucanson

An interpreter for Vaucanson Louis-Noel Pouchet <[email protected]> Technical Report no0413, revision 0.4, 06 2004 Vaucanson is a generic framework for finite state machine manipulation. There is a need for that kind of library to be able to work in a dynamic environment. Two previous solutions were developed to provide an interpreter for Vaucanson. This report propose another attempt to realize an interpreter, using Swig and OCaml. Also, a syntax proposal is done for automata manipulation. Keywords Vaucanson, interpreter, Swig, OCaml Laboratoire de Recherche et Développement de l’Epita 14-16, rue Voltaire – F-94276 Le Kremlin-Bicêtre cedex – France Tél. +33 1 53 14 59 47 – Fax. +33 1 53 14 59 22 [email protected] – http://www.lrde.epita.fr 2 Copying this document Copyright c 2004 LRDE. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with the Invariant Sections being just “Copying this document”, no Front- Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is provided in the file COPYING.DOC. Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Context of this research 5 2.1 Vaucanson ......................................... 5 2.2 Possible solutions ..................................... 5 2.3 Existing solutions ..................................... 5 2.3.1 The first interpreter for Vaucanson ....................... 6 2.3.2 Vaucanswig .................................... 6 2.4 Another interpreter .................................... 7 3 Interpreter building 9 3.1 Used tools ......................................... 9 3.1.1 Swig ........................................ 9 3.1.2 OCaml ...................................... -

Fresh Objective Caml User Manual

UCAM-CL-TR-621 Technical Report ISSN 1476-2986 Number 621 Computer Laboratory Fresh Objective Caml user manual Mark R. Shinwell, Andrew M. Pitts February 2005 15 JJ Thomson Avenue Cambridge CB3 0FD United Kingdom phone +44 1223 763500 http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/ c 2005 Mark R. Shinwell, Andrew M. Pitts Technical reports published by the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory are freely available via the Internet: http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/TechReports/ ISSN 1476-2986 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 About the language . 5 1.2 Obtaining and installing Fresh O'Caml . 5 1.3 The toplevel system . 6 1.4 Batch compilation . 6 2 Concrete syntax 9 2.1 Keywords . 9 2.2 Values . 9 2.3 Type expressions . 10 2.4 Patterns . 10 2.5 Expressions . 10 3 Handling of binding operations 11 3.1 Types of bindable names . 11 3.2 Abstraction values and types . 11 3.3 Declaring fresh atoms . 12 3.4 Structural equality and alpha-conversion . 13 3.5 Abstraction patterns . 14 3.6 Swapping bindable names . 16 3.7 The freshness relation . 18 3.8 Abstraction types in general . 18 3.9 Reference cells . 20 Bibliography 21 3 1 Introduction 1.1 About the language Fresh O'Caml extends Objective Caml (www.ocaml.org) to provide seamless and cor- rect manipulation of object language binding constructs inside a metalanguage. The language enables the programmer to concentrate on the algorithmic essence of their syntax-manipulating programs, without having to concern themselves with the te- dious matters of ensuring that properties of ®-convertible object language names are correctly respected.