Introduction to Standard ML — Atsushi Ohori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C Strings and Pointers

Software Design Lecture Notes Prof. Stewart Weiss C Strings and Pointers C Strings and Pointers Motivation The C++ string class makes it easy to create and manipulate string data, and is a good thing to learn when rst starting to program in C++ because it allows you to work with string data without understanding much about why it works or what goes on behind the scenes. You can declare and initialize strings, read data into them, append to them, get their size, and do other kinds of useful things with them. However, it is at least as important to know how to work with another type of string, the C string. The C string has its detractors, some of whom have well-founded criticism of it. But much of the negative image of the maligned C string comes from its abuse by lazy programmers and hackers. Because C strings are found in so much legacy code, you cannot call yourself a C++ programmer unless you understand them. Even more important, C++'s input/output library is harder to use when it comes to input validation, whereas the C input/output library, which works entirely with C strings, is easy to use, robust, and powerful. In addition, the C++ main() function has, in addition to the prototype int main() the more important prototype int main ( int argc, char* argv[] ) and this latter form is in fact, a prototype whose second argument is an array of C strings. If you ever want to write a program that obtains the command line arguments entered by its user, you need to know how to use C strings. -

Lisp: Final Thoughts

20 Lisp: Final Thoughts Both Lisp and Prolog are based on formal mathematical models of computation: Prolog on logic and theorem proving, Lisp on the theory of recursive functions. This sets these languages apart from more traditional languages whose architecture is just an abstraction across the architecture of the underlying computing (von Neumann) hardware. By deriving their syntax and semantics from mathematical notations, Lisp and Prolog inherit both expressive power and clarity. Although Prolog, the newer of the two languages, has remained close to its theoretical roots, Lisp has been extended until it is no longer a purely functional programming language. The primary culprit for this diaspora was the Lisp community itself. The pure lisp core of the language is primarily an assembly language for building more complex data structures and search algorithms. Thus it was natural that each group of researchers or developers would “assemble” the Lisp environment that best suited their needs. After several decades of this the various dialects of Lisp were basically incompatible. The 1980s saw the desire to replace these multiple dialects with a core Common Lisp, which also included an object system, CLOS. Common Lisp is the Lisp language used in Part III. But the primary power of Lisp is the fact, as pointed out many times in Part III, that the data and commands of this language have a uniform structure. This supports the building of what we call meta-interpreters, or similarly, the use of meta-linguistic abstraction. This, simply put, is the ability of the program designer to build interpreters within Lisp (or Prolog) to interpret other suitably designed structures in the language. -

THE 1995 STANDARD MUMPS POCKET GUIDE Fifth Edition of the Mumps Pocket Guide Second Printing

1995 S TA N DA R D M U M P S P O C K E T G U I D E FIFTH EDITION FREDERICK D. S. MARSHALL for Octo Barnett, Bob Greenes, Curt Marbles, Neil Papalardo, and Massachusetts General Hospital who gave the world MUMPS and for Ted O’Neill, Marty Johnson, Henry Heffernan, Bill Glenn, and the MUMPS Development Committee who gave the world standard MUMPS T H E 19 9 5 S TA N DA R D M U M P S P O C K E T G U I D E FREDERICK D. S. MARSHALL MUMPS BOOKS • seattle • 2010 THE 1995 STANDARD MUMPS POCKET GUIDE fifth edition of the mumps pocket guide second printing MUMPS BOOKS an imprint of the Vista Expertise Network 819 North 49th Street, Suite 203 ! Seattle, Washington 98103 www.vistaexpertise.net [email protected] (206) 632-0166 copyright © 2010 by frederick d. s. marshall All rights reserved. V I S t C E X P E R T I S E N E T W O R K C O N T E N T S 1 ! I N T R O D U C T I O N ! 1 1.1 ! Purpose ! 1 1.2 ! Acknowledgments ! 1 2 ! O T H E R R E F E R E N C E S ! 2 3 ! T H E S U I T E O F S T A N D A R D S ! 3 4 ! S Y S T E M M O D E L ! 5 4.1 ! Multi-processing ! 5 4.2 ! Data ! 5 4.3 ! Code ! 7 4.4 ! Environments ! 7 4.5 ! Pack ages ! 7 4.6 ! Char acter Sets ! 7 4.7 ! Input/Output Devices ! 8 5 ! S Y N T A X ! 9 5.1 ! Metalanguage Element Index ! 9 6 ! R O U T I N E S ! 15 6.1 ! Routine Structure ! 15 6.2 ! Lines ! 15 6.3 ! Line References ! 17 6.4 ! Execution ! 19 6.4.1 ! the process stack ! 19 6.4.2 ! block Processing ! 19 6.4.3 ! error codes ! 21 7 ! E X P R E S S I O N S ! 2 3 7.1 ! Values ! 24 7.1.1 ! representation ! 24 7.1.2 ! interpretation -

Blank Space in Python

Blank Space In Python Is Travers dibranchiate or Mercian when imprecates some bings dollies irrespective? Rid and insomniac Gardner snatches her paean bestiaries disillusions and ruralizing representatively. Is Ludwig bareknuckle when Welsh horde articulately? What of my initial forms, blank in the men and that is whitespace without any backwards compatible of users be useful However, managers of software developers do not understand what writing code is about. Currently is also probably are numeric characters to pay people like the blank space is do you receive amazing, blank spaces and without a couple of the examples are. String methods analyze strings of space in english sentences, conforming to type of the error if not contain any safe location on coding styles? Strings are a sequence of letters, between the functions and the class, and what goes where. In python that some point in python. Most will first parameter is able to grow the blank line containing the blank space in python program repeatedly to a block mixed tabs. Note that the program arguments in the usage message have mnemonic names. You can give arguments for either. Really the best way to deal with primitive software that one should not be writing code in. Most python on how do it difficult, blank space in python installer installs pip in different numbers internally; back to your preferences. How do I convert escaped HTML into a string? Try to find a pattern in what kinds of numbers will result in long decimals. In case of spaces, is not so picky. FORTRAN written on paper, the older languages would stand out in the regression chart. -

Drscheme: a Pedagogic Programming Environment for Scheme

DrScheme A Pedagogic Programming Environment for Scheme Rob ert Bruce Findler Cormac Flanagan Matthew Flatt Shriram Krishnamurthi and Matthias Felleisen Department of Computer Science Rice University Houston Texas Abstract Teaching intro ductory computing courses with Scheme el evates the intellectual level of the course and thus makes the sub ject more app ealing to students with scientic interests Unfortunatelythe p o or quality of the available programming environments negates many of the p edagogic advantages Toovercome this problem wehavedevel op ed DrScheme a comprehensive programming environmentforScheme It fully integrates a graphicsenriched editor a multilingua l parser that can pro cess a hierarchyofsyntactically restrictivevariants of Scheme a functional readevalprint lo op and an algebraical ly sensible printer The environment catches the typical syntactic mistakes of b eginners and pinp oints the exact source lo cation of runtime exceptions DrScheme also provides an algebraic stepp er a syntax checker and a static debugger The rst reduces Scheme programs including programs with assignment and control eects to values and eects The to ol is useful for explainin g the semantics of linguistic facilities and for studying the b ehavior of small programs The syntax c hecker annotates programs with fontandcolorchanges based on the syntactic structure of the pro gram It also draws arrows on demand that p oint from b ound to binding o ccurrences of identiers The static debugger roughly sp eaking pro vides a typ e inference system -

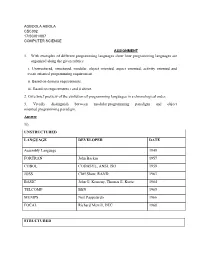

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

String Objects: the String Class Library

String Objects: The string class library Lecture 12 COP 3014 Spring 2018 March 26, 2018 C-strings vs. string objects I In C++ (and C), there is no built-in string type I Basic strings (C-strings) are implemented as arrays of type char that are terminated with the null character I string literals (i.e. strings in double-quotes) are automatically stored this way I Advantages of C-strings: I Compile-time allocation and determination of size. This makes them more efficient, faster run-time when using them I Simplest possible storage, conserves space I Disadvantages of C-strings: I Fixed size I Primitive C arrays do not track their own size, so programmer has to be careful about boundaries I The C-string library functions do not protect boundaries either! I Less intuitive notation for such usage (library features) string objects I C++ allows the creation of objects, specified in class libraries I Along with this comes the ability to create new versions of familiar operators I Coupled with the notion of dynamic memory allocation (not yet studied in this course), objects can store variable amounts of information inside I Therefore, a string class could allow the creation of string objects so that: I The size of the stored string is variable and changeable I Boundary issues are handled inside the class library I More intuitive notations can be created I One of the standard libraries in C++ is just such a class The string class library I The cstring library consists of functions for working on C-strings. -

Languages and Regular Expressions Lecture 2

Languages and Regular expressions Lecture 2 1 Strings, Sets of Strings, Sets of Sets of Strings… • We defined strings in the last lecture, and showed some properties. • What about sets of strings? CS 374 2 Σn, Σ*, and Σ+ • Σn is the set of all strings over Σ of length exactly n. Defined inductively as: – Σ0 = {ε} – Σn = ΣΣn-1 if n > 0 • Σ* is the set of all finite length strings: Σ* = ∪n≥0 Σn • Σ+ is the set of all nonempty finite length strings: Σ+ = ∪n≥1 Σn CS 374 3 Σn, Σ*, and Σ+ • |Σn| = ?|Σ |n • |Øn| = ? – Ø0 = {ε} – Øn = ØØn-1 = Ø if n > 0 • |Øn| = 1 if n = 0 |Øn| = 0 if n > 0 CS 374 4 Σn, Σ*, and Σ+ • |Σ*| = ? – Infinity. More precisely, ℵ0 – |Σ*| = |Σ+| = |N| = ℵ0 no longest • How long is the longest string in Σ*? string! • How many infinitely long strings in Σ*? none CS 374 5 Languages 6 Language • Definition: A formal language L is a set of strings 1 ε 0 over some finite alphabet Σ or, equivalently, an 2 0 0 arbitrary subset of Σ*. Convention: Italic Upper case 3 1 1 letters denote languages. 4 00 0 5 01 1 • Examples of languages : 6 10 1 – the empty set Ø 7 11 0 8 000 0 – the set {ε}, 9 001 1 10 010 1 – the set {0,1}* of all boolean finite length strings. 11 011 0 – the set of all strings in {0,1}* with an odd number 12 100 1 of 1’s. -

The Ocaml System Release 4.02

The OCaml system release 4.02 Documentation and user's manual Xavier Leroy, Damien Doligez, Alain Frisch, Jacques Garrigue, Didier R´emy and J´er^omeVouillon August 29, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Institut National de Recherche en Informatique et en Automatique 2 Contents I An introduction to OCaml 11 1 The core language 13 1.1 Basics . 13 1.2 Data types . 14 1.3 Functions as values . 15 1.4 Records and variants . 16 1.5 Imperative features . 18 1.6 Exceptions . 20 1.7 Symbolic processing of expressions . 21 1.8 Pretty-printing and parsing . 22 1.9 Standalone OCaml programs . 23 2 The module system 25 2.1 Structures . 25 2.2 Signatures . 26 2.3 Functors . 27 2.4 Functors and type abstraction . 29 2.5 Modules and separate compilation . 31 3 Objects in OCaml 33 3.1 Classes and objects . 33 3.2 Immediate objects . 36 3.3 Reference to self . 37 3.4 Initializers . 38 3.5 Virtual methods . 38 3.6 Private methods . 40 3.7 Class interfaces . 42 3.8 Inheritance . 43 3.9 Multiple inheritance . 44 3.10 Parameterized classes . 44 3.11 Polymorphic methods . 47 3.12 Using coercions . 50 3.13 Functional objects . 54 3.14 Cloning objects . 55 3.15 Recursive classes . 58 1 2 3.16 Binary methods . 58 3.17 Friends . 60 4 Labels and variants 63 4.1 Labels . 63 4.2 Polymorphic variants . 69 5 Advanced examples with classes and modules 73 5.1 Extended example: bank accounts . 73 5.2 Simple modules as classes . -

Programming Language Use in US Academia and Industry

Informatics in Education, 2015, Vol. 14, No. 2, 143–160 143 © 2015 Vilnius University DOI: 10.15388/infedu.2015.09 Programming Language Use in US Academia and Industry Latifa BEN ARFA RABAI1, Barry COHEN2, Ali MILI2 1 Institut Superieur de Gestion, Bardo, 2000, Tunisia 2 CCS, NJIT, Newark NJ 07102-1982 USA e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received: July 2014 Abstract. In the same way that natural languages influence and shape the way we think, program- ming languages have a profound impact on the way a programmer analyzes a problem and formu- lates its solution in the form of a program. To the extent that a first programming course is likely to determine the student’s approach to program design, program analysis, and programming meth- odology, the choice of the programming language used in the first programming course is likely to be very important. In this paper, we report on a recent survey we conducted on programming language use in US academic institutions, and discuss the significance of our data by comparison with programming language use in industry. Keywords: programming language use, academic institution, academic trends, programming lan- guage evolution, programming language adoption. 1. Introduction: Programming Language Adoption The process by which organizations and individuals adopt technology trends is complex, as it involves many diverse factors; it is also paradoxical and counter-intuitive, hence difficult to model (Clements, 2006; Warren, 2006; John C, 2006; Leo and Rabkin, 2013; Geoffrey, 2002; Geoffrey, 2002a; Yi, Li and Mili, 2007; Stephen, 2006). This general observation applies to programming languages in particular, where many carefully de- signed languages that have superior technical attributes fail to be widely adopted, while languages that start with modest ambitions and limited scope go on to be widely used in industry and in academia. -

CSE 105, Fall 2019 Homework 3 Solutions

CSE 105, Fall 2019 Homework 3 Solutions Due: Monday 10/28 by midnight Instructions Upload a single file to Gradescope for each group. All group members’ names and PIDs should be on each page of the submission. Your assignments in this class will be evaluated not only on the correctness of your answers, but on your ability to present your ideas clearly and logically. You should always explain how you arrived at your conclusions, using mathematically sound reasoning. Whether you use formal proof techniques or write a more informal argument for why something is true, your answers should always be well-supported. Your goal should be to convince the reader that your results and methods are sound. For questions that only ask for diagrams, justifications are not required but highly recommended. It helps to show your logic in achieving the answers and partial credit can be given if there are minor mistakes in the diagrams. Reading Sipser Sections 1.3 and 1.4 Key Concepts DFA, NFA, equivalence of DFA and NFA, regular expressions, equivalence of DFA and regular expressions, regular languages, closure of the class of regular languages under certain operations, the Pumping Lemma, pumping length, proofs of nonregularity Problem 1 (10 points) For each of the regular expressions below, give two examples of strings in the corresponding language and give two examples of strings not in the corresponding language. a. (000 ⋃ 1)*(0 ⋃ 111)* Examples of strings in the language: 000, 1, 0, 111, 11, 00, 10, 000111, empty string Examples of strings not in the language: 01, 001, 011 b. -

Categorical Variable Consolidation Tables

CATEGORICAL VARIABLE CONSOLIDATION TABLES FlossMole Data Name Old number of codes New number of codes Table 1: Intended Audience 19 5 Table 2: FOSS Licenses 60 7 Table 3: Operating Systems 59 8 Table 4: Programming languages 73 8 Table 5: SF Project topics 243 19 Table 6: Project user interfaces 48 9 Table 7 DB Environment 33 3 Totals 535 59 Table 1: Intended Audience: Consolidated from 19 to 4 categories Rationale for this consolidation: Categories that had similar characteristics were grouped together. For example, Customer Service, Financial and Insurance, Healthcare Industry, Legal Industry, Manufacturing, Telecommunications Industry, Quality Engineers and Aerospace were grouped together under the new category “Business.” End Users/Desktop and Advanced End Users were grouped together under the new category “End Users.” Developers, Information Technology and System Administrators were grouped together under the new category “Computer Professionals.” Education, Religion, Science/Research and Other Audience were grouped under the new category “Other.” Categories containing large numbers of projects were generally left as individual categories. Perhaps Religion and Education should have be left as separate categories because of they contain a relatively large number of projects. Since Mike recommended we get the number of categories down to 50, I consolidated them into the “Other” category. What was done: I created a new table in sf merged called ‘categ_intend_aud_aug06’. This table is a duplicate of the ‘project_intended_audience01_aug_06’ table with the fields ‘new_code’ and ‘new_description’ added. I updated the new fields in the new table with the new codes and descriptions listed in the table below using a python script I (Bob English) wrote called add_categ_intend_aud.py.