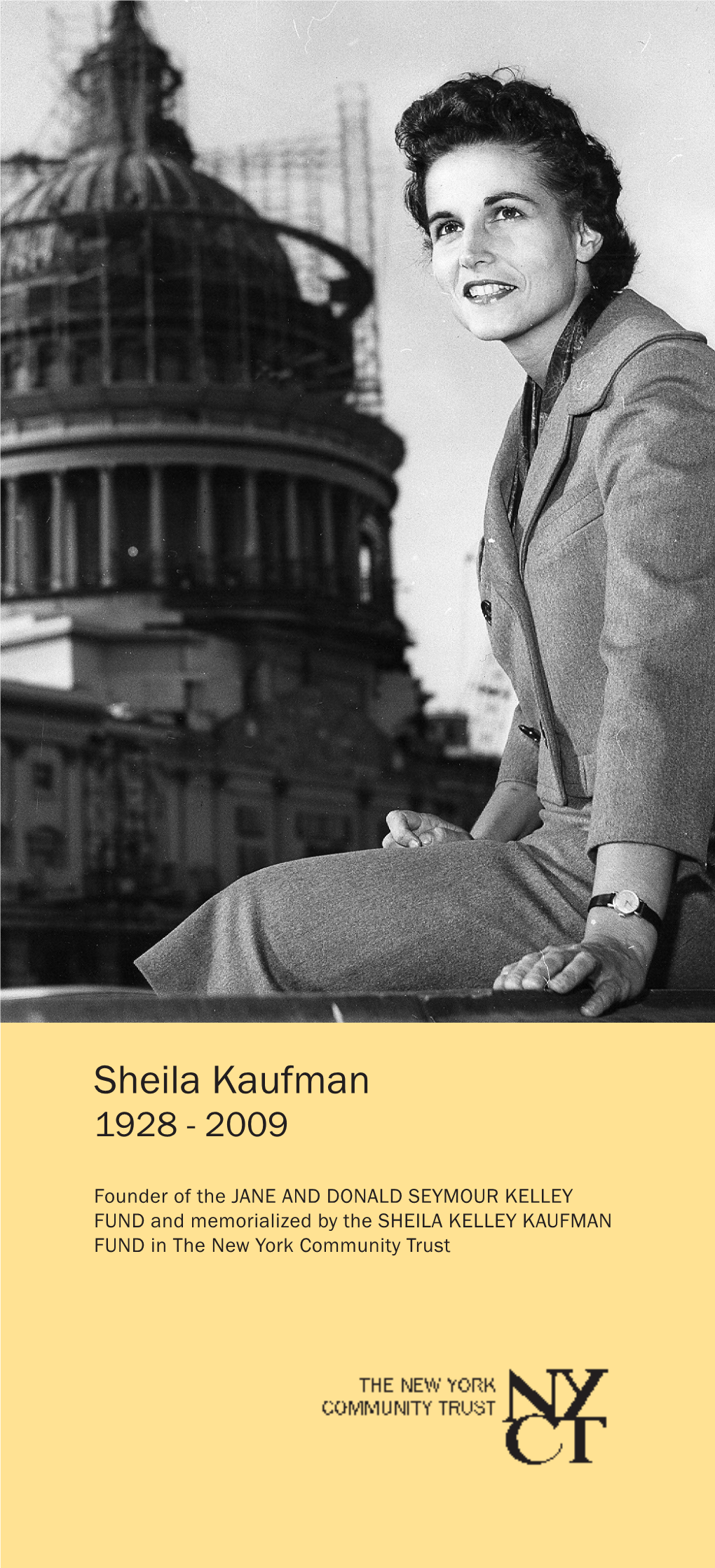

Kaufman, Sheila Kelley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Wilderness Years (1962 – 1968) Collection

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Wilderness Years (1962 – 1968) Collection Series I: Correspondence Sub-Series A: Alphabetical Box 1-39: Correspondence Files. 1963-1965. Sorted. (PPS 238) Box 40-48: Correspondence Files. 1966-1968. Sorted. (PPS 230) Sub-Series B: Social and Political Correspondence Box 1-6: Correspondence Files. Form and guide letters. 1960-1968. (PPS 243) Box 7-10: Correspondence File. Form Letter Answers. (PPS 231) Box 11-13: Correspondence Files. Outgoing correspondence files. ca. June 1961-Oct. 1962. (PPS 245) Box 14-21: Correspondence Files. Various files – Social and political correspondence. 1965- 1968. (PPS 247) Box 22-25: Correspondence Files. Anne Volz Higgins Personal, Social, Political Correspondence. 1967. (PPS 248) Box 26-32: Correspondence Files. Secretaries source file, Ann V. Higgins – form letters (1964- 1968). Materials compiled in three 3-ring notebooks. (PPS 250) Correspondence Files. Mailing lists and campaign thank yous. (PPS 250A) Box 33- :Correspondence Files. 1960-1968 Campaigns. X (extra) copies. – Arranged alphabetically. (PPS 246) Sub-Series C: Appearances and Invitations Box 1-4: Correspondence. Correspondence re: Appearances, Contributions, and Interviews. (PPS 227) Box 5: Correspondence relating to RN’s 1961-1962 schedule: California invitations, turn downs, and pending. (PPS 228) Box 6: Correspondence File. 1960-1964. (PPS 232) Box 7-14: Correspondence Files. Speaking invitations and turn downs. 1963-1967. (PPS 237) Box 15-18: Correspondence re: invitations. 1963-1967. Arranged by State (PPS 234) Box 19-20: Correspondence. College speaking invitations. 1963-1967. (PPS 229) Sub-Series D: Law Firms Box 1: Correspondence: Adams, Duque & Hazeltine (PPS 238) Box 2: Correspondence. 1963. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

IHH11I on BUY WA^A ^Article Ingrid Bergman H Ask Betty to Sign Her Screen Name Rockville

Mr. Sturges Prefers real robust muscle characters, and Army because of his asthma—the AMUSEMENTS. Where When Is teaching them to act. same reason used in the script to and show Bracken’s discharge from the Sturges uses only one real actor Current Theater Attractions Legitimate Toughs service. O’Keefe Still Feels in "Hail the Conquering Hero” in PROMPT CURTAIN! Kindly and Time of Showing For His Movies a supporting role to Eddie Bracken. Stage. By the Associated Press. He is William Demarest, an Army Back to Work N* Seatln* Darin* Flrat Namier Km. 8:10; Mali. Weal. Than. Set. 1:10 National—“Oklahoma!” The mu- With such a of sergeant of tVie First World War Toward His Theme conglomeration After an Oregon vacation with tTHI a NATION’S MUSICAL SSNSATION Song sical sensation: 2:30 and 8:30 war who plays veteran Marine. p.m. pictures in production, other husband Lt. Jack Reynolds, Mar- By JAY CARMODY. Screen. Sturges, a great fight fan, also directors may worry nights over jorie Reynolds* will return to Para- Capitol—"I Dood It,” a phrase In selected Freddy Steele, former mid- Music department: It is true that performers often do tire of num- OKLAHOMA action: 11 critical shortages of actors who look dleweight champ; Jimmy Dundee, mount for the second feminine lead ft. bers do over a.m., 1:40, 4:25, 7:15 and No Seals Available they and over again. But that is not true of Walter like hard-boiled soldiers instead 9:55 p.m. Stage shows: of who for 30 years has made up to (next to Joan in O'Keefe and "The Daring Man on the 12:55, 3:45, Bennett) “Up in Young Flying Trapeze.” 6:30 and 9:10 sissies, but not Preston Sturges. -

Battle of the Brains: Election-Night Forecasting at the Dawn of the Computer Age

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: BATTLE OF THE BRAINS: ELECTION-NIGHT FORECASTING AT THE DAWN OF THE COMPUTER AGE Ira Chinoy, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Emeritus Maurine Beasley Philip Merrill College of Journalism This dissertation examines journalists’ early encounters with computers as tools for news reporting, focusing on election-night forecasting in 1952. Although election night 1952 is frequently mentioned in histories of computing and journalism as a quirky but seminal episode, it has received little scholarly attention. This dissertation asks how and why election night and the nascent field of television news became points of entry for computers in news reporting. The dissertation argues that although computers were employed as pathbreaking “electronic brains” on election night 1952, they were used in ways consistent with a long tradition of election-night reporting. As central events in American culture, election nights had long served to showcase both news reporting and new technology, whether with 19th-century devices for displaying returns to waiting crowds or with 20th-century experiments in delivering news by radio. In 1952, key players – television news broadcasters, computer manufacturers, and critics – showed varied reactions to employing computers for election coverage. But this computer use in 1952 did not represent wholesale change. While live use of the new technology was a risk taken by broadcasters and computer makers in a quest for attention, the underlying methodology of forecasting from early returns did not represent a sharp break with pre-computer approaches. And while computers were touted in advance as key features of election-night broadcasts, the “electronic brains” did not replace “human brains” as primary sources of analysis on election night in 1952. -

John Wanamaker Collection 2188

John Wanamaker collection 2188 Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania ; March 2013 John Wanamaker collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 Series I. Personal records........................................................................................................................ 9 Series II. Store records.......................................................................................................................... 32 Series III. Miscellaneous -

Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2017 Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis Gregory I. Ruth Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sports Management Commons Recommended Citation Ruth, Gregory I., "Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis" (2017). Dissertations. 2848. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2848 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2017 Gregory I. Ruth LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PANCHO’S RACKET AND THE LONG ROAD TO PROFESSIONAL TENNIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY GREGORY ISAAC RUTH CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2017 Copyright by Gregory Isaac Ruth, 2017 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Three historians helped to make this study possible. Timothy Gilfoyle supervised my work with great skill. He gave me breathing room to research, write, and rewrite. When he finally received a completed draft, he turned that writing around with the speed and thoroughness of a seasoned editor. Tim’s own hunger for scholarship also served as a model for how a historian should act. I’ll always cherish the conversations we shared over Metropolis coffee— topics that ranged far and wide across historical subjects and contemporary happenings. -

![Reid Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2619/reid-family-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-4542619.webp)

Reid Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Reid Family Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2016 Revised 2016 November Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003038 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82065491 Prepared by David Mathisen, Grover Batts, and Audrey Walker Revised and expanded by Joseph K. Brooks with the assistance of Patricia Craig and Susie Moody in 2001, and Maria Farmer and Dan Oleksiw in 2016 Collection Summary Title: Reid Family Papers Span Dates: 1795-2003 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1869-1970) ID No.: MSS65491 Creator: Reid family Extent: 261,000 items ; 932 containers plus 2 oversize ; 372.8 linear feet ; 239 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Journalists and newspaper publishers. Correspondence, financial records, office files, household and estate records, subject files, scrapbooks, printed matter, and miscellaneous papers related to newspaper publishing and public affairs. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Adams, Franklin P. (Franklin Pierce), 1881-1960--Correspondence. Alsop, Joseph, 1910-1989--Correspondence. Andrews, Bert, 1901-1953--Correspondence. Astor, David, Hon., 1912-2001--Correspondence. Babcock, John V. (John Vincent)--Correspondence. Bagdikian, Ben H. Barrett, Lois A.--Correspondence. Bigart, Homer, 1907-1991--Correspondence. Bing, André, 1910 or 1911-1973--Correspondence. -

David Sarnoff Papers 2464.55

David Sarnoff papers 2464.55 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library David Sarnoff papers 2464.55 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................... 10 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Controlled Access Headings ........................................................................................................................ 13 Collection Inventory .................................................................................................................................... -

Tune in , Between Issues ••• '1'0

This kind of arithmetic may put Johnny through college Hcre's how it works out: bonds may very well be the means of helping you educate your children as you'd like to have $3 put into U. S. Savings Bonds today w ill them educated. bring back $4 in 10 years. So keep on buying Savings Bonds-available Another $ 3 w ill bring bock onother $4. at banks and post offices. Or the way that mil So it's quite right to figure that 3 plus 3 equals lions have found easiest and surest-through 8 . or 30 plus 30 equals 80 ... or 300 plus Payroll Savings. Hold on to all you've bought. 300 equals 800! You'll be mighty glad you did . .. 10 years It will ... in U. S. Savings Bonds. And those from now! SAVE THE -EASY WAY. .. BUY YOUR BONOS THROUGH PAYROLL SAVINGS Contributed by this magazine in cooperation with the Magazine Publishers of America as a public service TUNE IN , BETWEEN ISSUES ••• '1'0 ... 110 • • "" ... .... h .. .tI.. uttw 1110-.,,11 0 .... ' .... oel,... '~ ..I<I .. Winston Churchill receiving lucrative bids to head new radio network in this country. Seems doubtful that he'll ~ccept ••• Helen Hayes A_hIO ,<lIMn refusing to do woman cOUlDe.ntary program ••• Walt Ton)' ...... """.,. eaIooII ... Disney preparing radio show based on the cartoon characters he's made famous ••• Jeri SuI la "O'an of the Bob Crosby show mak ing her t1rst movie ••• Cary Grant and Clark Gable were first orficial passengers on Guy CONTINTS Lombardo's new airline, run- ~ IX~I~ ,.xG..Ul.~ _ ning between Long Island towns ~ SOli' OAT Till WOIIII WILL JUIIII and New York City ••• Bob Burns received wire IIIDICUUD IUT IIIWAIIDEOI ., .. -

Introducing the Incomparable Hildegarde: the Sexuality, Style, and Image of a Forgotten Cultural Icon Monica Gallamore Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Introducing the Incomparable Hildegarde: The Sexuality, Style, and Image of a Forgotten Cultural Icon Monica Gallamore Marquette University Recommended Citation Gallamore, Monica, "Introducing the Incomparable Hildegarde: The exS uality, Style, and Image of a Forgotten Cultural Icon" (2012). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 196. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/196 INTRODUCING THE INCOMPARABLE HILDEGARDE: THE SEXUALITY, STYLE, AND IMAGE OF A FORGOTTEN CULTURAL ICON by Monica S. Gallamore A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2012 ABSTRACT INTRODUCING THE INCOMPARABLE HILDEGARDE: THE SEXUALITY, STYLE, AND IMAGE OF A FORGOTTEN CULTURAL ICON Monica S. Gallamore Marquette University, 2012 This study is an historical biography of the popular American entertainer from the nineteen-forties and fifties named Hildegarde. Known by her first name long before such designations became commonplace, Hildegarde achieved such celebrity status that she influenced women‘s fashions and promoted a number of consumer products. She even had her own signature Revlon lipstick and nail polish called ―Hildegarde Rose.‖ Hildegarde‘s career spanned for more than seventy years, beginning as a pianist for silent movies in Milwaukee and eventually becoming the darling of nightclubs and supper clubs. Unfortunately, few people remember this entertainer or her influence. She has been overlooked by historians as a cultural influence and a groundbreaking performer even though in 1945 she was the most popular songstress in the nation. Hildegarde is unique because she did not fit into the accepted archetype of women during her heyday. -

The Maine Broadcaster : June 1948 (Vol. 4, No. 6)

Portland Public Library Portland Public Library Digital Commons The Maine Broadcaster Local History Collections 6-1948 The Maine Broadcaster : June 1948 (Vol. 4, No. 6) Maine Broadcasting System (WCSH Portland, ME) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/mainebroadcaster TBE MAINE BROADCASTER PUBLISHED AS AN AID TO BETTER RADIO LISTENING Vol. IV, No. 6, Portland, Maine, June, 1948 Price, Five Cents SUMMER PROGRAMS ANNOUNCED BY NBC 1 Former 'Baron Munchausen' To Many Old Timers Be Heard Again I:ri~New Series Will Make Bid Jack Pearl, famed comedy srar of plications which arise from his duties stage and .radio, and his perennial as ~ager of his own business. side-kick Cliff Hall, will rerum to "The Great Gildersleeve" program J'\BC co headline "TI1e Jack Pearl uow heard in th.is time spot leaves For Come-Back Show," beginning \Vednesday, J une the air for the summer with the June A. galaxy of srars and programs 9 (8:30 p. m.,). _ 2. broadcast. w ill be added to the NBC summer Pearl remrns to the air under the Scripts will be written by Paul S. schedule within the next few weeks. sponsorship of the U. Treasury De Harrison, Joseph O'Brien and Bernie S. Comedy, drama, variety, music and partment to which NBC has donated Gould. Paul S. Harrison will direct. quiz shows arc among the newcomers this time period. Music will be supplied by the four co commercial and sustaining program The comediao was best known on harmonizing Kelly Sisters, and a 25- spors. XBC - from 1932 to 1937 - as "Baron piece orchestra under direction of RFD America joins the NBC •\ lw1chauseo," whose exaggerated Milton Katims. -

RCA News and Information Department Photographs 2464.68

RCA News and Information Department photographs 2464.68 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library RCA News and Information Department photographs 2464.68 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 9 Collection Inventory ......................................................................................................................................