Mackey a Phd 2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blackburn Cathderal Newsletter

1 Howard was your editor’s most generous host when he (JB) and Lords Lieutenant, High Sheriffs and Mayors round every was invited to lead a Master-Class for the choristers of Chichester corner – yet Howard looked after his own guest superbly. In and Winchester Cathedrals at the Southern Cathedrals’ Festival in other words, he is not only supremely efficient (as we in Chichester last summer. Blackburn know) but also a most gracious and generous Howard lives in the Close, right next door to the Deanery, in a friend. It was a most happy visit. most delightful ‘Tardis’ house which is considerably bigger inside Although Howard than out. From one of his three guest bedrooms there’s an has three assistant unparalleled view of the cathedral. His garden, too, is exquisite. vergers, yet he is always on call through his mobile phone. He dealt with at least one crisis most calmly and efficiently: the loudspeaker system had a glitch, which had to be rectified before a major service. Within half an hour all was well, and no one, apart from Howard and his assistant, knew what he had done. Even though he was rushed off his feet during the four very It was such privilege for your editor to lead a 75-minute busy days of the Festival – for not only were there two visiting Master Class with the choristers of Chichester and cathedral choirs, Winchester and Salisbury, but also their Girls’ Winchester, for they were so talented, so professional and choirs, and clergy of those two cathedrals plus a visiting orchestra, so co-operative. -

Magnificat JS Bach

Whitehall Choir London Baroque Sinfonia Magnificat JS Bach Conductor Paul Spicer SOPRANO Alice Privett MEZZO-SOPRANO Olivia Warburton TENOR Bradley Smith BASS Sam Queen 24 November 2014, 7. 30pm St John’s Smith Square, London SW1P 3HA In accordance with the requirements of Westminster City Council persons shall not be permitted to sit or stand in any gangway. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment is strictly forbidden without formal consent from St John’s. Smoking is not permitted anywhere in St John’s. Refreshments are permitted only in the restaurant in the Crypt. Please ensure that all digital watch alarms, pagers and mobile phones are switched off. During the interval and after the concert the restaurant is open for licensed refreshments. Box Office Tel: 020 7222 1061 www.sjss.org.uk/ St John’s Smith Square Charitable Trust, registered charity no: 1045390. Registered in England. Company no: 3028678. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Choir is very grateful for the support it continues to receive from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). The Choir would like to thank Philip Pratley, the Concert Manager, and all tonight’s volunteer helpers. We are grateful to Hertfordshire Libraries’ Performing Arts service for the supply of hire music used in this concert. The image on the front of the programme is from a photograph taken by choir member Ruth Eastman of the Madonna fresco in the Papal Palace in Avignon. WHITEHALL CHOIR - FORTHCOMING EVENTS (For further details visit www.whitehallchoir.org.uk.) Tuesday, 16 -

Judith Bingham

RES10108 THE EVERLASTINGCROWN JUDITH BINGHAM Stephen Farr - Organ The Everlasting Crown Judith Bingham (b. 1952) The Everlasting Crown (2010) 1. The Crown [3:52] Stephen Farr organ 2. Coranta: Atahualpa’s Emerald [3:20] 3. La Pelegrina [4.38] 4. The Orlov Diamond [2:56] 5. The Russian Spinel [4:22] 6. King Edward’s Sapphire [5:34] 7. The Peacock Throne [7:09] About Stephen Farr: Total playing time [31:54] ‘ superbly crafted, invigorating performances, combining youthful vigour and enthusiasm with profound musical insight and technical fluency’ All tracks are world premiere recordings and were Gramophone recorded in the presence of the composer ‘[...] in a superb and serious organ-recital matinee by Stephen Farr, the chief work was the world premiere of The Everlasting Crown by Judith Bingham’ The Observer The Everlasting Crown The gemstone is seen as somehow drawing these events towards itself: its unchanging Ideas for pieces often, for me, result from and feelingless nature causes the inevitable coming across oddball books, be it anthologies ruin of the greedy, ambitious, foolish and of poetry, or out of print rarities. A few years foolhardy, before passing on to the next ago I came across Stories about Famous victim. One wonders why anyone craves the Precious Stones by Adela E. Orpen (1855- ownership of the great stones as their history 1927), published in America in 1890. In this is of nothing but ruin and despair! All of the book, it is not the scholarship that matters, stones in this piece can still be seen, many more the romance and mythology of the of them in royal collections, some in vaults. -

The Magazine of the Guild of Church Musicians No 95 May 2018 Laudate

The Magazine of the Guild of Church Musicians No 95 May 2018 Laudate Laudate is typeset by Michael Walsh HonGCM and printed by St Richard’s Press Leigh Road, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8TU [email protected] 01243 782988 www. From the Editor of Laudate It is wlth great relief that I can confirm that our Salisbury meeting on Saturday 7 July is now ‘safe’ and you will find full details of this, together with our 22 September Arundel meeting, included in this edition. Please do return the enclosed form to me as soon as possible so we can work out our catering needs for the day. I do hope that as our work expands around the country you will feel moved to join us for these events. We are planning a number of courses and events of a practical nature for the start of next year, so in due course please let me know your views on these, plus any suggestions for events you’d like to see us offering. Patrons: Rt Revd & Rt Hon Dr Richard Chartres, former Lord Bishop of London In this issue we conclude our series on hymn tunes with two interesting articles on Professor Dr Ian Tracey, Organist Titulaire of Liverpool Cathedral the subject, plus a number of musical examples at the end of the magazine for you Dame Patricia Routledge to play through (but not copy please!). Several of these fine tunes were unknown to Master: Professor Dr Maurice Merrell me and I hope that you will enjoy getting to know them. -

Choral & Organ Awards Booklet

INDIVIDUAL COLLEGE PAGES Christ’s 2 Churchill 3 Clare 4 Corpus Christi 6 Downing 8 Emmanuel 9 Fitzwilliam 11 Girton 13 Gonville & Caius 15 Homerton 17 Jesus 19 King’s 21 King’s Voices 22 Magdalene 23 Newnham (see Selwyn) 35 Pembroke (Organ Awards only) 24 Peterhouse 26 Queens’ 28 Robinson 30 St Catharine’s 31 St John’s 32 St John’s Voices 34 Selwyn 35 Sidney Sussex 37 Trinity 39 Trinity Hall 41 1 CHRIST’S COLLEGE www.christs.cam.ac.uk In addition to singing for service twice weekly in College, Christ’s choir pursues an exciting range of activities outside of Chapel, regularly performing in London and around the UK, recording CDs, broadcasting, and undertaking major international tours. The choir is directed by the Director of Music, performer and musicologist David Rowland, assisted by the Organ Scholars. Organ Scholarships The College normally has two Organ Scholars who assist the Director of Music in running and directing the Chapel choir. Organ scholars may study any subject except Architecture and the College has a history of appointing individuals reading science subjects as well as arts and humanities. The organ scholars are also encouraged to play a full part in other College musical activities through the Music Society, which offers opportunities for orchestral and choral conducting, as well as the chance to perform in chamber recitals, musicals, etc. In addition to the honorarium which an Organ Scholar receives each year, the College pays for organ lessons. Both organ scholars have designated rooms in college that are equipped with pianos and practice organs. -

A Publication of the Newark United Methodist C Hurch March 2016

March Worship at Newark United Methodist Church Lenten Reflection Self-Guided Stations of the Cross A self-guided Stations of the Cross has been set up in the Chapel. Participants may either use the iPod audiotour or the printed booklet to guide them through March 2016 March this Lenten journey of prayer and meditation. Please stop by whenever the building is open! A great time to experience the Stations of the Cross is before our weekly Lenten Taizé service on Wednesday evenings. The stations take about 20 minutes from start to finish. Lenten Taiz Services Join us in the Chapel at 7pm on Wednesdays through March 16 for a time of peace and reflection—a grace-filled experience. Holy Week Maundy Thursday, March 24: 7pm Worship for all (Heritage Hall) Good Friday, March 25: 7pm Choral Tenebrae with the NUMC Chancel Choir and guest musicians from the University of Delaware. New: The Good Morning Good Friday program for children ages 3 through 6th grade will be held from 9am-noon on Friday, 3/25. This interactive program is a wonderful way to teach our children about the events of Maundy Thursday and Good Friday. The program is limited to about 30 children, so sign up early! We are also looking for volunteers to assist in making cookie dough, baking, and supervising the groups of children on the day of the event. Look for the sign-up sheets in Heritage Hall or contact the Christian Education office if you'd like to participate or volunteer ([email protected]; 302-368-8774, x225). -

Bulletin.Pdf

MOBILE SECTION / HIGH CONTRAST SECTION / PRINTABLE SECTION The leading website for organ recitals in Britain. 50,695 concerts by 4,231 organists have been listed at 1,956 venues. Q-links: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z < > [ ] ( ) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 @ & ▼ ▼ ▼ CLICK HERE TO ADVERTISE RECITALS ONE WEBSITE • THOUSANDS OF CONCERTS CLICK HERE FOR WEEKLY BULLETINS organrecitals.com Jump to: SATURDAY 4 MAY SUNDAY 5 MONDAY 6 TUESDAY 7 WEDNESDAY 8 THURSDAY 9 FRIDAY 10 7 Days: All / London Mornings Lunchtimes Afternoons Evenings Bank Holidays Weekends: All / London AAREASREAS VVENUESENUES Search... OORGANISTSRGANISTS DDATESATES Summary: Next 100 Inaugural, Anniversary, etc. Two or More Organ Plus Silent Movies Cinema Organs Days Universities Mayfair Westminster London Zones London Notables Programmes New Listings Cancelled WEEKLY BULLETIN Click on a county, day/date, month, venue, or organist for more recitals. Click on a postcode for a map or on a picture for street view. Suffolk IP9 2RX 10:15 1 Send details by e-mail • Copy and paste details Saturday 4 May 2019 East of England Organ Day [info] Royal Hospital School Chapel, Holbrook Christian Wilson [organ] [venue] [tickets] [location & enquiries] (H.M. Chapel Royal, Tower of London) admission £8 100 years of music from both sides of the Atlantic To report changes to this entry: e-mail [email protected], quoting ref. 58704 Greater Manchester BL1 1PS 11:00 to 12:00 2 Send details by e-mail • Copy and paste details Saturday 4 May 2019 Bolton Parish Church Michael Pain [organ] [info] [venue] [location & enquiries] (Bolton Parish Church) admission £6 / concessions £4 / under-16s free To report changes to this entry: e-mail [email protected], quoting ref. -

SEPTEMBER 2018 All Saints Episcopal Church Southern Shores

THE DIAPASON SEPTEMBER 2018 All Saints Episcopal Church Southern Shores, North Carolina Cover feature on pages 26–27 ANTHONY & BEARD ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO JAMES DAVID CHRISTIE PETER RICHARD CONTE CONTE & ENNIS DUO LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD SIMON THOMAS JACOBS MARTIN JEAN HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE LOUPRETTE & GOFF DUO ROBERT MCCORMICK BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAéL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN ROBIN & LELEU DUO BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH JOSHUA STAFFORD THOMAS GAYNOR 2016 2017 LONGWOOD GARDENS ST. ALBANS WINNER WINNER IT’S ALL ABOUT THE ART ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ 860-560-7800 ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚͬWŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Ninth Year: No. 9, A new season Whole No. 1306 As I write this on August 1, I realize you will read this at SEPTEMBER 2018 the end of this month or early September, the very last days of Established in 1909 summer. Most choirs and ensembles will soon begin rehears- Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 als for their weekly services or seasonal concerts. The staff of 847/954-7989; [email protected] The Diapason hopes that these past weeks and months have www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, provided you a bit of respite from the myriad activities you will the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music soon experience. 20 Under 30 Our “Here & There” section this month contains listings for The Diapason’s 20 Under 30 program returns in December! CONTENTS many church, university, civic, and regional ensembles that will We will recognize once again young women and men whose FEATURES excite you with opportunities for excellence in organ and choral career accomplishments place them at the forefront of the organ, The 1864 William A. -

Choral & Organ Awards Booklet

INDIVIDUAL COLLEGE PAGES Christ’s 2 Churchill 3 Clare 5 Corpus Christi 7 Downing 8 Emmanuel 9 Fitzwilliam 11 Girton 13 Gonville & Caius 15 Homerton 17 Jesus 19 King’s 21 King’s Voices 22 Magdalene 23 Newnham (see Selwyn) 35 Pembroke (Organ Awards only) 24 Peterhouse 26 Queens’ 28 Robinson 30 St Catharine’s 31 St John’s 32 St John’s Voices 34 Selwyn 35 Sidney Sussex 37 Trinity 39 Trinity Hall 41 1 CHRIST’S COLLEGE www.christs.cam.ac.uk In addition to singing for service twice weekly in College, Christ’s choir pursues an exciting range of activities outside of Chapel, regularly performing in London and around the UK, recording CDs, broadcasting, and undertaking major international tours. The choir is directed by the Director of Music, performer and musicologist David Rowland, assisted by the Organ Scholars. Organ Scholarships The College normally has two Organ Scholars who assist the Director of Music in running and directing the Chapel choir. Organ scholars may study any subject except Architecture and the College has a history of appointing individuals reading science subjects as well as arts and humanities. The organ scholars are also encouraged to play a full part in other College musical activities through the Music Society, which offers opportunities for orchestral and choral conducting, as well as the chance to perform in chamber recitals, musicals, etc. In addition to the honorarium which an Organ Scholar receives each year, the College pays for organ lessons. Both organ scholars have designated rooms in college that are equipped with pianos and practice organs. -

Press Information

PRESS INFORMATION News Desk From: To: Christine Doyle Date: Thursday 11th September 2014 Tel: 07769738180 Coventry Cathedral’s lunchtime organ concert on Monday 15th September at 1pm On Monday 15th September the guest organist at the Cathedral’s lunchtime concert will be Benjamin Chewter from Chester Cathedral. Benjamin will be performing Veni Creator Spiritus (1: Plein Jeu, 2: Fugue à 5, 3: Duo, 4: Récit du Cromorne, 5: Dialogue sur les Grands Jeux) by de Grigny, Ave Maria, Ave Maris Stella (Trois Paraphrases Grégoriennes, Op.5 No.2) by Langlais, Aria by Peeters and Allegro deciso (Evocation) by Dupré. Admission to the lunchtime concert series is free of charge. For details of all the concerts, visit www.coventrycathedral.org.uk or pick up a leaflet at the Cathedral entrance or Gift Shop. -ends- Notes to Editors Benjamin Chewter is the Assistant Director of Music at Chester Cathedral where he is responsible for the accompaniment of the statutory services; he also assists with the training of the choristers and directs the Cathedral’s Nave Choir. Benjamin was educated at Christ's Hospital School and held the Organ Scholarship at Canterbury Cathedral before going up to Emmanuel College, Cambridge as Organ Scholar (where he read Music and was Organist of King’s Voices, the mixed-voice choir of King’s College Chapel). Subsequently he held the Organ Scholarship at Westminster Abbey and was Assistant Organist of Lincoln Cathedral for three years before taking up his current post. As an organist and conductor he has performed extensively throughout the UK (at venues including Westminster Abbey, Lichfield, Gloucester, St Paul’s, Canterbury, St Albans and Westminster Cathedrals, and St John's Smith Square in London) and abroad (Sweden, Mexico, Latvia, France, Belgium, Poland and Germany). -

July2007fullissue.Pdf

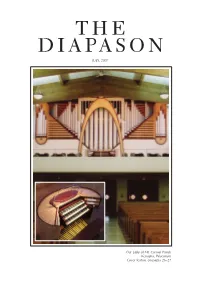

THE DIAPASON JULY, 2007 Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Parish Kenosha, Wisconsin Cover feature on pages 26–27 “The 50th anniversary celebration of the Bach Festival culminated in a very impressive organ recital by Huw Lewis. A performer with an international reputation, he presented an almost-all-Bach program of thoroughly challenging works....With panache, Lewis deftly negotiated the many moods and rapid-fire register changes that make this work (Liszt BACH) such a dynamic closing number.” (Kalamazoo Gazette MI) “Dr. Lewis played with great authority, but also with an elegance and sensitivity to style, room, and instrument, and received the first standing ovation of the [AGO] convention.” (The American Organist) “Superb music, superbly executed...His repertoire includes the greatest, most demanding of the master works for organ and he plays them with great understanding, technical mastery and sensitivity....Lewis, with incredible technical skill, kept everything under control and tasteful.” (The Holland Sentinel MI) “Apart from being immensely enjoyable, it was an object lesson in how to prepare for, and give, a performance at the highest level on an instrument not of your choosing. Another memorable feature was the marvelous freshness of [his] playing following so many hours of grinding practice.” (K. B. Lyndon, RCCO, London ON) HuwHuw LewisLewis Concert Organist Faculty, Hope College, Holland, Michigan “I must tell you how delighted we were with the masterful performance by Huw Lewis...I am thrilled with the musicality of his playing. Anyone who can command the attention of an audience made up of non-concert- goers on the most gorgeous Sunday afternoon of the fall while playing a Bach Trio-Sonata on the most mediocre of instruments is an artist indeed.” (Larry L. -

The Cornopean

The Cornopean EXETER & DISTRICT ORGANISTS’ ASSOCIATION Newsletter June 2021 IN THIS ISSUE Gary Cole of Regent records p9 Editorial p2 David Flood looks back p15 President’s Letter p3 Ian Carson’s Organ Tour Pt 4 p17 “Desert Island Discs ” p4 Nerdy Corner p19 Obituary p6 Exe Cruise Booking Form p21 Nerdy Corner & Answers p15 p6 Forthcoming Events p20 James Lancelot remembers (Pt 4) p6 Future Event p18 1 Editorial Please make a note in your diary of the Presidents’ Congratulations also to James Anderson-Besant, Evening – a river cruise on the Exe Estuary on the currently Assistant Organist at St John’s College, evening of Thursday 8th July, departing from Cambridge, on being appointed to succeed Exmouth Quay at 6:45pm. This should be a Timothy Parsons as Assistant Director of Music at splendid way for us to get together again after the Exeter Cathedral. He will also take up his position privations of the last year. There will be a buffet in September. Since Tim has already departed for supper (under cover in case of inclement St Edmundsbury Cathedral, his place during the weather) and a cash bar. There is a booking form summer term is being taken by James McVinnie – at the back of this edition of The Cornopean. Book Acting Assistant Director of Music. early as places will be limited. Further details and a booking form are on page 21. I am sorry to report the death of Richard Lloyd, former Organist of both Hereford and Durham Cathedrals. Alan Thurlow who worked with Richard at Durham Cathedral (later Organist & Master of the Choristers at Chichester Cathedral) has written an obituary, published on page 5.