Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Percy Fitzpatrick Institute of African Ornithology Annual Report

Percy FitzPatrick Institute DST/NRF Centre of Excellence Annual Report January – December 2009 Department of Zoology University of Cape Town Private Bag X3 Rondebosch 7701 SOUTH AFRICA +27 (0)21 650 3290/1 [email protected] http://www.fitzpatrick.uct.ac.za University of Cape Town Contents Director’s report 1 Staff and Students 3 Research Programmes & Initiatives • Systematics and Biogeography 5 • Cooperation and Sociality in birds 13 • Rarity and Conservation of African birds 19 • Island Conservation 26 • Seabird Research 28 • Raptor Research 33 • Spatial Parasitology and Epidemiology 36 • Pattern-process Linkages in Landscape 39 Ecology • Environmental & Resource Economics 41 • Climate Change Vulnerability and 44 Adaptation • And a Miscellany 49 Conservation Biology Masters 53 Board Members: Programme Niven Library 55 Mr M. Anderson (BirdLife SA) Scientific Publications 59 Mr H. Amoore (UCT, Registrar) Dr G. Avery (Wildlife and Environment Society of Southern Africa) Semi-popular Publications 63 Prof. K. Driver (UCT, Dean of Science, Chairman) Prof. P.A.R. Hockey (UCT, Director, PFIAO) Seminars 2009 65 Assoc. Prof. J. Hoffmann (UCT, HoD, Zoology) Mr P.G. Johnson (co-opted) Dr J. McNamara (UCT, Development & Alumni Dept) Prof. M.E. Meadows (UCT, HoD, ENGEO) Mr C.A.F. Niven (FitzPatrick Memorial Trust) Mr J.D.F. Niven (FitzPatrick Memorial Trust) Mr P.N.F. Niven (FitzPatrick Memorial Trust) Mr F. van der Merwe (co-opted) Prof. D. Visser (UCT, Chairman, URC) The Annual Report may also be viewed on the Percy FitzPatrick Institute's website: http://www.fitzpatrick.uct.ac.za Director’s Report Director’s Report To say that 2009 was a busy and eventful year would be an understatement! Early in January, Doug Loewenthal, Graeme Oatley and I participated in the Biodiversity Academy at De Hoop Nature Reserve. -

Island Biology Island Biology

IIssllaanndd bbiioollooggyy Allan Sørensen Allan Timmermann, Ana Maria Martín González Camilla Hansen Camille Kruch Dorte Jensen Eva Grøndahl, Franziska Petra Popko, Grete Fogtmann Jensen, Gudny Asgeirsdottir, Hubertus Heinicke, Jan Nikkelborg, Janne Thirstrup, Karin T. Clausen, Karina Mikkelsen, Katrine Meisner, Kent Olsen, Kristina Boros, Linn Kathrin Øverland, Lucía de la Guardia, Marie S. Hoelgaard, Melissa Wetter Mikkel Sørensen, Morten Ravn Knudsen, Pedro Finamore, Petr Klimes, Rasmus Højer Jensen, Tenna Boye Tine Biedenweg AARHUS UNIVERSITY 2005/ESSAYS IN EVOLUTIONARY ECOLOGY Teachers: Bodil K. Ehlers, Tanja Ingversen, Dave Parker, MIchael Warrer Larsen, Yoko L. Dupont & Jens M. Olesen 1 C o n t e n t s Atlantic Ocean Islands Faroe Islands Kent Olsen 4 Shetland Islands Janne Thirstrup 10 Svalbard Linn Kathrin Øverland 14 Greenland Eva Grøndahl 18 Azores Tenna Boye 22 St. Helena Pedro Finamore 25 Falkland Islands Kristina Boros 29 Cape Verde Islands Allan Sørensen 32 Tristan da Cunha Rasmus Højer Jensen 36 Mediterranean Islands Corsica Camille Kruch 39 Cyprus Tine Biedenweg 42 Indian Ocean Islands Socotra Mikkel Sørensen 47 Zanzibar Karina Mikkelsen 50 Maldives Allan Timmermann 54 Krakatau Camilla Hansen 57 Bali and Lombok Grete Fogtmann Jensen 61 Pacific Islands New Guinea Lucía de la Guardia 66 2 Solomon Islands Karin T. Clausen 70 New Caledonia Franziska Petra Popko 74 Samoa Morten Ravn Knudsen 77 Tasmania Jan Nikkelborg 81 Fiji Melissa Wetter 84 New Zealand Marie S. Hoelgaard 87 Pitcairn Katrine Meisner 91 Juan Fernandéz Islands Gudny Asgeirsdottir 95 Hawaiian Islands Petr Klimes 97 Galápagos Islands Dorthe Jensen 102 Caribbean Islands Cuba Hubertus Heinicke 107 Dominica Ana Maria Martin Gonzalez 110 Essay localities 3 The Faroe Islands Kent Olsen Introduction The Faroe Islands is a treeless archipelago situated in the heart of the warm North Atlantic Current on the Wyville Thompson Ridge between 61°20’ and 62°24’ N and between 6°15’ and 7°41’ W. -

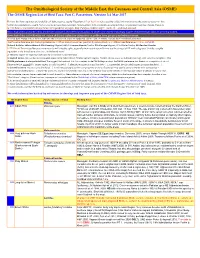

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club Volume 134 No. 2 June 2014 FORTHCOMING MEETINGS See also BOC website: http://www.boc-online.org BOC MEETINGS are open to all, not just BOC members, and are free. Evening meetings are held in an upstairs room at The Barley Mow, 104 Horseferry Road, Westminster, London SW1P 2EE. The nearest Tube stations are Victoria and St James’s Park; and the 507 bus, which runs from Victoria to Waterloo, stops nearby. For maps, see http://www.markettaverns.co.uk/the_barley_mow. html or ask the Chairman for directions. The cash bar opens at 6.00 pm and those who wish to eat after the meeting can place an order. The talk will start at 6.30 pm and, with questions, will last c.1 hour. It would be very helpful if those intending to come can notify the Chairman no later than the day before the meeting. Tuesday 23 September 2014—6.30 pm—Dr Andrew Gosler—Ornithology to ethno-ornithology Abstract: Why are we ornithologists? Because we are fascinated by birds, yes, but why are humans so captivated by the ecology, evolution and behaviour of another vertebrate group that a UK Government Chief Scientist should complain that a disproportionate amount was spent on bird research to the detriment of other taxa? Whatever the answer to this, the fact that humans everywhere are enthralled by birds should point the way to how we might engage, re-engage or differently engage people in all countries with nature, and so focus resources most effectively for its conservation. -

Arabian Peninsula

THE CONSERVATION STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE BREEDING BIRDS OF THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Compiled by Andy Symes, Joe Taylor, David Mallon, Richard Porter, Chenay Simms and Kevin Budd ARABIAN PENINSULA The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM - Regional Assessment About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature-based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with almost 1,300 government and NGO Members and more than 15,000 volunteer experts in 185 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by almost 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of around 7,500 experts. SSC advises IUCN and its members on the wide range of technical and scientific aspects of species conservation, and is dedicated to securing a future for biodiversity. SSC has significant input into the international agreements dealing with biodiversity conservation. About BirdLife International BirdLife International is the world’s largest nature conservation Partnership. BirdLife is widely recognised as the world leader in bird conservation. -

Percy Fitzpatrick Institute of African Ornithology DST/NRF Centre of Excellence

Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology DST/NRF Centre of Excellence 50th Anniversary Annual Report 2010 Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology DST/NRF Centre of Excellence 50th Anniversary Annual Report 2010 www.fitzpatrick.uct.ac.za Cecily Niven Dr Max Price Founder of the Percy FitzPatrick Institute Vice-Chancellor, University of Cape Town The Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology at The Percy FitzPatrick Institute is one of the jewels in the University of Cape Town was founded in 1960 through the crown of the University of Cape Town. This is an accolade the vision and drive of Cecily Niven, daughter of Sir Percy acknowledged both nationally and internationally, not only FitzPatrick of Jock of the Bushveld fame, after whom the by the Institute’s status as a National Centre of Excellence, Institute is named. Cecily passed away in 1992, but her but also by a recent report from an international review Institute continues to go from strength to strength. It is panel which places the Institute alongside its two global the only ornithological research institute in the southern counterparts at Cornell and Oxford Universities. It gives me hemisphere, and one of only a handful in the world. great pleasure to endorse the Institute’s 50th Anniversary Report and to wish it success into the future. Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology DST/NRF Centre of Excellence 50th Anniversary Annual Report 2010 Contents 6 Director’s Report 65 Ducks, dispersal and disease: The movements 10 Profiling & media exposure -

C:\Users\Jennings\1 ABBA\Forms Updated\Forms\Form 2 3-11.Wpd

ABBA Form 2 (3/11) LIST OF THE BREEDING BIRDS OF ARABIA (Please note this list, including the nomenclature and taxonomic order is under review and will be bought in line with that of the Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Arabia which was published in July 2010. Also the status notes do not in all cases reflect the up to date situation. This is also being reviewed). The species listed here are those known to have bred in Arabia or are very likely to breed. The order follows the List of recent Holarctic bird species by K. H. Voous (published by the British Ornithologists Union, 1977) but certain changes have been made to bird names to accord with present usage. The reference number shown on the left is the number to be inserted in Column 2 of the ABBA Report sheet Form 3. The few breeding species not on the Voous list (these are mainly ferally breeding exotics) are given a separate sequence commencing with 2001. The Breeding Evidence Code (BEC) used by the ABBA project should be read in conjunction with this list. Details of species additional to the list, for which breeding is proven (BEC 10 or higher), will be published in future issues of Phoenix. Observers suspecting or proving breeding of species not shown on the list should make a full report. Highly sedentary species are identified with an asterisk (*). Because presence of these species, even outside the breeding season, is a good indication of local breeding. BEC "XX" may be used to report occurrence in suitable habitat at any time. -

The Populations and Distribution of the Breeding Birds of the Socotra Archipelago, Yemen: 1

The populations and distribution of the breeding birds of the Socotra archipelago, Yemen: 1. Sandgrouse to Buntings RF Porter & AHMED SAEED SULEIMAN This is the first of two papers on the distribution and population of the breeding birds of the Socotra archipelago, that have been studied in detail since 1999. It covers all the passerines and some non-passerines, including nine species that are endemic to the archipelago. A second paper will cover the remaining non-passerines. For each species there is a map showing breeding distribution, an estimate of the population based on a comprehensive series of transects, and brief notes on habitat and breeding biology. Of the 25 species covered many are widespread and occur in a variety of habitats, with the five most abundant being Socotra Sparrow Passer insularis, Black- crowned Sparrow-Lark Eremopterix nigriceps, Laughing Dove Spilopelia senegalensis, Somali Starling Onychognathus blythii and Long-billed Pipit Anthus similis. All 25 are resident, except for Forbes- Watson’s Swift Apus berliozi. The only globally threatened species covered in this paper are the Abd Al Kuri Sparrow Passer hemileucus and Socotra Bunting Emberiza socotrana (both vulnerable), whilst the Socotra Cisticola Cisticola haesitatus is classified as near threatened. INTRODUCTION The Socotra archipelago (Figure 1) is famed for its unique flora and fauna, with over 350 species of endemic plants, at least 21 endemic reptiles and ten species of endemic birds (Cheung & DeVantier 2006, Porter & Suleiman 2011). For plant endemism per square kilometre alone Socotra island is ranked in the top ten islands in the world (Banfield et al 2011). -

SOCOTRA Archipelago

Republic of Yemen SOCOTRA Archipelago Proposal for inclusion in the World Heritage List | UNESCO January 2006 cover Dracaena cinnibari Photo by Mario Caruso INDEX 0. Executive Summary . 5 1. Identification of the Property . 9 2. Description of the Property . 21 3. Justification for Inscription . 69 4. State of conservation and factors affecting the property . 79 5. Protection and Management . 101 6. Monitoring . 127 7. Documentation . 135 8. Contact Information of responsible authorities . 161 9. Signature on behalf of the State Party . 165 A. List of annexes . 167 3 0. Executive Summary State Party 0.Executive Yemen Summary State, Province and Region Hadramawt Name of Property Socotra Archipelago Geographical coordinates to the nearest second (see maps at page 11) ID No. Nome of the area Discrict Corea Area (ha) Buffer Zone (ha) Coordinates Terrestrial Marine Terrestrial Marine xxxx-001 Socotra Hadramawt N 12° 30’ 00” - E 53° 50’ 00” A: 242.903 a: 2.739 1: 64.845 840.325 B: 17.105 b: 7.157 2: 18.252 c: 578 3: 8.900 d: 1.106 e: 30.412 f: 764 g: 3.098 h: 14.187 sub-total 260.008 60.041 91.997 840.325 xxxx-002 Abd Alkuri Hadramawt N 12° 11’ 22” - E 52° 14’ 21” 11.858 a: 1.885 456.179 b: 2.351 c: 638 sub-total 11.858 4.874 456.179 xxxx-003 Samha Hadramawt 5.063 26.917 243.083 N 12° 09’ 33” - E 53° 02’ 32” xxxx-004 Darsa Hadramawt 544 17.624 109.374 N 12° 07’ 25” - E 53° 16’ 24” xxxx-005 Kalfarun Hadramawt 31 11.072 N 12° 26’ 22” - E 52° 08’ 08” xxxx-006 Sabunya Hadramawt 8 12.420 91.997 N 12° 38’ 13” - E 53° 09’ 26” TOTAL 277.512 132.948 91.997 1.648.961 TOTAL 410.460 1,740,958.00 Textual description of the boundaries of the nominated property The Archipelago is located in the North-Western Indian Ocean and includes the main islands of So- cotra (or Soqotra), Abd al-Kuri, Samha and Darsa, as well as the smaller islets of Sabuniya and Kal Farun, and other rock outcrops. -

Republic of Yemen National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan for Yemen (NBSAPY) - (EPA) Draft document January, 2005 Republic of Yemen National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan ``For a sustainable and decent standard of living of Yemeni people while respecting the limits of nature and the integrity of creation.`` January, 2005 Ministry of Water and Environment Environment Protection Authority (EPA) UNDP/GEF/IUCN YEM/96/G31 1 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan for Yemen (NBSAPY) - (EPA) Draft document January, 2005 Republic of Yemen National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Table of contents Foreword by Prime Minister Preface by Minister of Water and Environment Preface by the Environment Protection Authority Acknowledgements Executive summary INTRODUCTION The convention on biological diversity A national endeavour for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development A portrait of biodiversity in Yemen The role and importance of biodiversity for Yemen Major threats to biodiversity in Yemen THE NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY A national vision Guiding principles Main strategic goals Goal 1. Conservation of natural resources 1. Protected Areas 2. Endemic and Endangered Species 3. Ex situ Conservation 4. Alien Invasive Species Goal 2. Sustainable use of natural resources 5. Terrestrial Wildlife Resources (Fauna and Flora) 6. Coastal/Marine Life and Fisheries 7. Agro-biodiversity (Agriculture and Animal Production) Goal 3. Integrating biodiversity in sectoral development plans 8. Infrastructures and Industry 9. Biotechnology and Biosafety 10. Tourism and Eco-tourism 11. Urban, Rural Development and Land Use Planning 12. Waste Management 13. Water Management 14. Climate Change and Energy 2 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan for Yemen (NBSAPY) - (EPA) Draft document January, 2005 Goal 4. -

1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals

The tUCN Species Survival Commission 1996 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals Compiled and Edited by Jonathan Baillie and Brian Groombridge The Worid Conseivation Union 9 © 1996 International Union for Conservation ot Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational and otfier non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is cited and the copyright holder receives a copy of the reproduced material. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of lUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: lUCN 1996. 1996 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. lUCN, Gland, Switzerland. ISBN 2-8317-0335-2 Co-published by lUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge U.K., and Conservation International, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. Available from: lUGN Publications Services Unit, 219c Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CBS ODL, United Kingdom. Tel: + 44 1223 277894; Fax: + 44 1223 277175; E-mail: [email protected]. A catalogue of all lUCN publications can be obtained from the same address. Camera-ready copy of the introductory text by the Chicago Zoological Society, Brookfield, Illinois 60513, U.S.A. Camera-ready copy of the data tables, lists, and index by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 21 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 ODL, U.K. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Endemic Bunting Species (Aves, Passeriformes, Emberizidae, Emberiza Koslowi ) from the Eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

65 (1): 135 – 150 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2015. 4.5.2015 Phylogenetic relationships of endemic bunting species (Aves, Passeriformes, Emberizidae, Emberiza koslowi ) from the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Martin Päckert 1, Yue-Hua Sun 2, Patrick Strutzenberger 1, Olga Valchuk 3, Dieter Thomas Tietze 4 & Jochen Martens 5, # 1 Senckenberg Natural History Collections, Museum of Zoology, Königsbrücker Landstraße 159, 01109 Dresden, Germany — 2 Key Labora- tory of Animal Ecology and Conservation, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Science, 100101 Beijing, China — 3 Institute of Biology and Soil Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, 690022 Russia — 4 Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 364, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany — 5 Institut für Zoologie, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, 55099 Mainz, Germany — # Results of the Himalaya-Expeditions of J. Martens, No. 281. – For No. 280 see: Genus (Wrocław) 25 (3): 351 – 355, 2014 Accepted 20.iii.2015. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/vertebrate-zoology on 4.v.2015. Abstract In this study we reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships of a narrow-range Tibetan endemic, Emberiza koslowi, to its congeners and shed some light on intraspecific lineage separation of further bunting species from Far East Asia and along the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau in China. The onset of the Old World bunting radiation was dated to the mid Miocene and gave rise to four major clades: i) one group comprising mainly Western Palearctic species and all high-alpine endemics of the Tibetan Plateau; ii) a clade including E. lathami, E. bruniceps and E. melanocephala; iii) one group comprising mainly Eastern Palearctic species and all insular endemics from Japan and Sakhalin; iv) an exclusively Afrotropic clade that comprised all African species except E.