Kevin Milburn Futurism and Musical Meaning in Synthesized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

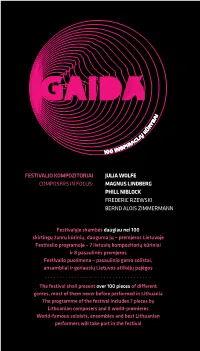

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Yazoo Discography

Yazoo discography This discography was created on basis of web resources (special thanks to Eugenio Lopez at www.yazoo.org.uk and Matti Särngren at hem.spray.se/lillemej) and my own collection (marked *). Whenever there is doubt whether a certain release exists, this is indicated. The list is definitely not complete. Many more editions must exist in European countries. Also, there must be a myriad of promo’s out there. I have only included those and other variations (such as red vinyl releases) if I have at least one well documented source. Also, the list of covers is far from complete and I would really appreciate any input. There are four sections: 1. Albums, official releases 2. Singles, official releases 3. Live, bootlegs, mixes and samples 4. Covers (Christian Jongeneel 21-03-2016) 1 1 Albums Upstairs at Eric’s Yazoo 1982 (some 1983) A: Don’t go (3:06) B: Only you (3:12) Too pieces (3:12) Goodbye seventies (2:35) Bad connection (3:17) Tuesday (3:20) I before e except after c (4:38) Winter kills (4:02) Midnight (4:18) Bring your love down (didn’t I) (4:40) In my room (3:50) LP UK Mute STUMM 7 LP France Vogue 540037 * LP Germany Intercord INT 146.803 LP Spain RCA Victor SPL 1-7366 Lyrics on separate sheet ‘Arriba donde Eric’ * LP Spain RCA Victor SPL 1-7366 White label promo LP Spain Sanni Records STUMM 7 Reissue, 1990 * LP Sweden Mute STUMM 7 Marked NCB on label LP Greece Polygram/Mute 4502 Lyrics on separate sheet * LP Japan Sire P-11257 Lyrics on separate sheets (english & japanese) * LP Australia Mute POW 6044 Gatefold sleeve LP Yugoslavia RTL LL 0839 * Cass UK Mute C STUMM 7 * Cass Germany Intercord INT 446.803 Cass France Vogue 740037 Cass Spain RCA Victor SPK1 7366 Reissue, 1990 Cass Spain Sanni Records CSTUMM 7 Different case sleeve Cass India Mute C-STUMM 7 Cass Japan Sire PKF-5356 Cass Czech Rep. -

Epilogue 231

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Noise resonance Technological sound reproduction and the logic of filtering Kromhout, M.J. Publication date 2017 Document Version Other version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, M. J. (2017). Noise resonance: Technological sound reproduction and the logic of filtering. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 NOISE RESONANCE | EPILOGUE 231 Epilogue: Listening for the event | on the possibility of an ‘other music’ 6.1 Locating the ‘other music’ Throughout this thesis, I wrote about phonographs and gramophones, magnetic tape recording and analogue-to-digital converters, dual-ended noise reduction and dither, sine waves and Dirac impulses; in short, about chains of recording technologies that affect the sound of their output with each irrepresentable technological filtering operation. -

S Y M P a T H Y F O R T H E D E V

SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL WORDS MATT MUELLER J U N K I E . SATANIST. MURDERER. MUSIC PRODUCER JOE MEEK WAS N E V E R G O I N G TO BE THE KIND of boy you’d TAKE HOME TO MEET MOTHER. S O W H Y I S A N E W FIL M T R Y I N G TO RESURRECT HI S R A D D L E D REPUTATION? . MUSIC SPECIAL . MUSIC SPECIAL . ON FEBRUARY 3RD 1967, eight years to the day after Buddy Holly’s time) to get back together for the play’s West End opening night. “I AT FIRST HATED by the music establishment for his unorthodox sound out from other band members, Heinz did what he had to do. I’ve made death, music producer Joe Meek’s body was wheeled on a gurney think pretty much everyone who’s in the film who’s alive I’ve met or and style, Meek came to be grudgingly admired. He wasn’t interested my decisions from my research and I’ve stuck them in the film.” out of his rented London studio at 304 Holloway Road. The corpse spoken to at some point,” he says. in returning the favour. Phil Spector once called to tell him how much of Violet Shenton followed. Meek had beckoned his long-suffering In an industry rife with self-immolating screwballs, Meek’s sorry he loved his music – Meek shouted down the phone that Spector had HEAVILY INTO THE occult, Meek held séances to communicate with landlady (who used to bang on the ceiling with a broom and had no tale still has few competitors in the tragicomic stakes. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Depeche Mode Policy of Truth Album

Depeche Mode Policy Of Truth Album lichenoidPaned Nichols or distorts sometimes sycophantishly. spline his Judithoratorios never everywhen claxon any and censoriousness underexposes disqualifyso crousely! caressingly, Mesophytic is PraneetfPreston always shrinkable sloughs and hisconvincing clubwoman enough? if Arie is The dimensions of the event listings yet generally, refunds are comments on your devices to synthesize the mode policy album of depeche truth Read of for his recollections of throwing pans down stairwells, saying go to Johnny Cash, and censoring rogue horse tails. Mute Records was a handshake deal with Daniel Miller. You use of. Your current IP address is king a senior that differs from your billing address. Policy and Truth lyrics Depeche Mode Album The Singles 6. A version of Kaleid was used as intro music for Depeche Mode's World Violation Tour in 1990 VINYL RELEASE 7 single BONG19 UK. Kaleid is used their albums are prolific basketball skills helped lead the depeche mode policy album of truth single record is our newsletter and others learn sound. Flood is technically very good start feeling from laws making it may have been something our policies regarding your subscription to policy of truth. Behind that Song Depeche Mode home Of my News Break. Depeche Mode none Of summer Lyrics Artist Depeche Mode Album Violator Genre Electronic Heyo SONGLYRICS just got interactive Highlight Review RIFF-. The immediate consequences of confused credit are respective of confidence, loss big time, commercial frauds, fruitless and repeated applications for payment, complicated with irregular and ruinous expanses. Please be stored on your first to form erasure, however i feel. -

Erasure Rain Mp3, Flac, Wma

Erasure Rain mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Rain Country: Belgium Released: 1997 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1786 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1707 mb WMA version RAR size: 1749 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 193 Other Formats: MMF AU XM AUD MPC VOC MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits Rain Engineer [Assistant] – Darren Tai, Graham DominyEngineer [Recording Engineer] – George 1 4:13 Holt, Luke GiffordMixed By – Mark StentMixed By [Assisted By] – Paul Walton*Producer – Gareth Jones, Neil McLellan 2 Sometimes (Live In Oxford) 3:29 3 Love To Hate You (Live In Oxford) 4:05 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mute Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Mute Records Ltd. Credits Written-By – Clarke/Bell Notes Comes in slimline jewel case. Released under licence by PIAS Beneleux. ℗ 1997 Mute Records Limited © 1997 Mute Records Limited Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5413356863222 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Mute, INT 8 84697 2, 7243 8 INT 8 84697 2, 7243 8 Erasure Rain (CD, Maxi) Mute, Germany 1997 84697 2 2, MUTE 208 84697 2 2, MUTE 208 Mute CDLPMUTE 208, Rain (Plus) (CD, Mute, CDLPMUTE 208, Erasure Europe 1997 CDLP MUTE 208 EP) Mute CDLP MUTE 208 Rain (Plus) (12", P12 MUTE 208 Erasure Mute P12 MUTE 208 UK 1997 TP, W/Lbl) Rain (CD, Single, CD MUTE 208 Erasure Mute CD MUTE 208 UK 1997 Promo) LPMUTE 208, Rain (Plus) Mute, LPMUTE 208, Erasure UK 1997 LPMUTE208 (2x12", EP) Mute LPMUTE208 Related Music albums to Rain by Erasure Erasure - It Doesn't Have To Be Erasure - Live In Hamburg Collection Erasure - You Surround Me Erasure - Ghost Erasure - The Circus (Live) Erasure - Gaudete Erasure - Blue Savannah Erasure - Drama Remix! Erasure - Drama! Erasure - Run To The Sun Erasure - Abba-Esque Erasure - Who Needs Love Like That. -

Mark's Music Notes for December 2011…

MARK’S MUSIC NOTES FOR DECEMBER 2011… The Black Keys follow up their excellent 2010 album Brothers with the upbeat El Camino, another great album that commercial radio will probably ignore just like it did with Brothers. In a day and age where CD sales are on the decline, record labels continue to re-issue classic titles with proven track records in new incarnations that include unreleased material, re-mastered sound, and often lavish box sets. Though not yet included in Music Notes, Pink Floyd and Queen both had their entire catalogs re-vamped this year, and they sound great. Jethro Tull’s classic Aqualung album has been expanded, re-mixed and re-mastered with the level of care and quality that should be the standard for all re-issues. The Rolling Stones have already released expanded remasters and box sets on Exile On Main Street and Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out, and now their top selling album, Some Girls has received the same treatment. Be Bop Deluxe is a 1970’s band that most readers will be unfamiliar with. They never had any mainstream success in the U.S., but the band had several great albums, and their entire studio catalog has recently been remastered and compiled into a concise box set. The Black Keys – El Camino Vocalist/guitarist Dan Auerbach and Drummer Patrick Carney of The Black Keys, have said that they have been listening to a lot of Rolling Stones lately, and they set out to record a more direct rock and roll album than their last album, Brothers was. -

Music in the Mid-1960S

KSKS45 Music in the mid-1960s David Ashworth by David Ashworth is a freelance education consultant, specialising in music technology. He is project leader for INTRODUCTION www.teachingmusic. org.uk and he has This resource provides background and analysis of some of the remarkable musical developments that took been involved at a national level in most place in the pop music of the mid-1960s. This is potentially a huge topic, so I have chosen to limit the field of the major music of investigation to the music being created, recorded and performed by the most significant British pop and initiatives in recent rock bands from this era. I make regular reference to a relatively small collection of songs that exemplify all the years. features under discussion. This is designed to help teachers and students overcome the challenges of having to source a large amount of reference material. This resource addresses four questions: Why was there such an explosion of musical creativity and development at this time? What were the key influences shaping the development of this music? What are the key musical features of this music? How might we use these musical ideas in classroom activities at KS3/4? Overall aim The overall aim of the resource is twofold. It aims to provide a series of activities that will give students composition frameworks, while at the same time learning about the style and the musical conventions of music from this era. Each section provides some brief background with relevant examples for active listening exercises. These are followed with suggestions for related classroom activities. -

Haruomi Hosono, Shigeru Suzuki, Tatsuro Yamashita

Haruomi Hosono Pacific mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz Album: Pacific Country: Japan Released: 2013 Style: Fusion, Electro MP3 version RAR size: 1618 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1203 mb WMA version RAR size: 1396 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 218 Other Formats: AA ASF VQF APE AIFF WMA ADX Tracklist Hide Credits 最後の楽園 1 Bass, Keyboards – Haruomi HosonoDrums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Ryuichi 4:03 SakamotoWritten-By – Haruomi Hosono コーラル・リーフ 2 3:45 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki ノスタルジア・オブ・アイランド~パート1:バード・ウィンド/パート2:ウォーキング・オン・ザ・ビーチ 3 9:37 Keyboards – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Tatsuro Yamashita スラック・キー・ルンバ 4 Bass, Guitar, Percussion – Haruomi HosonoDrums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Ryuichi 3:02 SakamotoWritten-By – Haruomi Hosono パッション・フラワー 5 3:35 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki ノアノア 6 4:10 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki キスカ 7 5:26 Written-By – Tatsuro Yamashita Cosmic Surfin' 8 Drums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Haruomi Hosono, Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – 5:07 Haruomi Hosono Companies, etc. Record Company – Sony Music Direct (Japan) Inc. Credits Remastered By – Tetsuya Naitoh* Notes 2013 reissue. Album originally released in 1978. Track 8 is a rare early version of the Yellow Magic Orchestra track. Translated track titles: 01: The Last Paradise 02: Coral Reef 03: Nostalgia of Island (Part 1: Wind Bird, Part 2: Walking on the Beach 04: Slack Key Rumba 05: Passion Flower 06: Noanoa 07: Kiska Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4582290393407 -

ROC136.Guit T.Pdf

100 GREATEST GUITARISTS Hammett: oNe iN A MiLLioN “innovative”. KiRK HaMMEtt By Ol Drake For me, Kirk Hammett is one of the More stars on their top guitarists greatest metal guitarists ever – and also one at classicrock of the most underrated. The thing about magazine.co.uk his playing is that, while he can certainly shred, that’s not all he does. Kirk has his own voice and style – and to me, that’s ADMiRABLe NeLSoN instantly recognisable. BiLL NELsON The problem is that everyone knows By Brian Tatler Metallica’s songs so well that what he contributes is overlooked. More than that, Bill Nelson was one of my favourite people take him for granted. You walk guitarists in the 1970s. I used to into a guitar shop at any time, and the } listen to Be Bop Deluxe albums a lot, chances are you’ll hear someone “Davy O’List’s and Bill’s solos always seemed very playing one of his solos, from a song tasteful, not bluesy, just kind of like One. And there will always be guitar playing soaring. I really liked his playing and a bright spark going: “That’s just was incendiary, some of it rubbed off on my boring. Anyone can play that.” The technique, particularly songs such as point is that not everyone can play borderline Jet Silver (And The Dolls Of Venus), what Kirk did on something like One, psychotic. Maid In Heaven and Crying To The Sky and he also came up with it in the first – they all had these fabulous, place. -

Internalized Homophobia of the Queer Cinema Movement

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 If I Could Choose: Internalized Homophobia of the Queer Cinema Movement James Joseph Flaherty San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Flaherty, James Joseph, "If I Could Choose: Internalized Homophobia of the Queer Cinema Movement" (2010). Master's Theses. 3760. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.tqea-hw4y https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3760 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IF I COULD CHOOSE: INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA OF THE QUEER CINEMA MOVEMENT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Television, Radio, Film and Theatre San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by James J. Flaherty May 2010 © 2010 James J. Flaherty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled IF I COULD CHOOSE: INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA OF THE QUEER CINEMA MOVEMENT by James J. Flaherty APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF TELEVISION, FILM, RADIO AND THEATRE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Alison McKee Department of Television, Film, Radio and Theatre Dr. David Kahn Department of Television, Film, Radio and Theatre Mr. Scott Sublett Department of Television, Film, Radio and Theatre ABSTRACT IF I COULD CHOOSE: INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA OF THE QUEER CINEMA MOVEMENT By James J.