Where Are the Lesbians? a Contested Political Existence in the Spanish Arena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Split at the Root: Prostitution and Feminist Discourses of Law Reform

Split at the Root: Prostitution and Feminist Discourses of Law Reform Margaret A. Baldwin My case is not unique. Violette Leduc' Today, adjustment to what is possible no longer means adjustment, it means making the possible real. Theodor Adorno2 This article originated in some years of feminist activism, and a sustained effort to understand two sentences spoken by Evelina Giobbe, an anti- prostitution activist and educator, at a radical feminist conference in 1987. She said: "Prostitution isn't like anything else. Rather, everything else is like prostitution because it is the model for women's condition."' Since that time, t Assistant Professor of Law, Florida State University College of Law. For my family: Mother Marge, Bob, Tim, John, Scharl, Marilynne, Jim, Robert, and in memory of my father, James. This article was supported by summer research grants from Florida State University College of Law. Otherwise, it is a woman-made product. Thanks to Rhoda Kibler, Mary LaFrance, Sheryl Walter, Annie McCombs, Dorothy Teer, Susan Mooney, Marybeth Carter, Susan Hunter, K.C. Reed, Margy Gast, and Christine Jones for the encouragement, confidence, and love. Evelina Giobbe, Kathleen Barry, K.C. Reed, Susan Hunter, and Toby Summer, whose contributions to work on prostitution have made mine possible, let me know I had something to say. The NCASA Basement Drafting Committee was a turning point. Catharine MacKinnon gave me the first opportunity to get something down on paper; she and Andrea Dworkin let me know the effort counted. Mimi Wilkinson and Stacey Dougan ably assisted in the research and in commenting on drafts. -

A Study of Feminine and Feminist Subjectivity in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Margaret Atwood and Adrienne Rich, 1950-1980 Little, Philippa Susan

Images of Self: A Study of Feminine and Feminist Subjectivity in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Margaret Atwood and Adrienne Rich, 1950-1980 Little, Philippa Susan The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1501 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Images of Self: A Study of Feminine and Feminist Subjectivity in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Margaret Atwood and Adrienne Rich, 1950-1980. A thesis supervised by Dr. Isobel Grundy and submitted at Queen Mary and Westfield College, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. by Philippa Susan Little June 1990. The thesis explores the poetry (and some prose) of Plath, Sexton, Atwood and Rich in terms of the changing constructions of self-image predicated upon the female role between approx. 1950-1980.1 am particularly concerned with the question of how the discourses of femininity and feminism contribute to the scope of the images of the self which are presented. The period was chosen because it involved significant upheaval and change in terms of women's role and gender identity. The four poets' work spans this period of change and appears to some extent generally characteristic of its social, political and cultural contexts in America, Britain and Canada. -

A Reply to Catharine Mackinnon Martha R

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 1993 Whiteness and Women, In Practice and Theory: A Reply To Catharine MacKinnon Martha R. Mahoney University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Law and Gender Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Martha R. Mahoney, Whiteness and Women, In Practice and Theory: A Reply To Catharine MacKinnon, 5 Yale J.L. & Feminism 217 (1993). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Whiteness and Women, In Practice and Theory: A Reply To Catharine MacKinnon Martha R. Mahoneyt I. INTRODUCTION As a white woman, I want to respond to Catharine MacKinnon's recent essay subtitled "What is a White Woman Anyway?"' I am troubled both by the essay's defensive tone and by its substantive arguments. 2 MacKinnon's contribution to feminism has emphasized the ways in which gender is constructed through male domination and sexual exploitation, and the profound structuring effect of male power on women's lives. This emphasis on what is done to women creates conceptual problems in understanding race and particularly in understanding whiteness. Defining gender by what is done to women makes it hard to see the many ways in which women act in our own lives and in the world. -

Notes for the Downloaders

NOTES FOR THE DOWNLOADERS: This book is made of different sources. First, we got the scanned pages from fuckyeahradicalliterature.tumblr.com. Second, we cleaned them up and scanned the missing chapters (Entering the Lives of Others and El Mundo Zurdo). Also, we replaced the images for new better ones. Unfortunately, our copy of the book has La Prieta, from El Mundo Zurdo, in a bad quality, so we got it from scribd.com. Be aware it’s the same text but from another edition of the book, so it has other pagination. Enjoy and share it everywhere! Winner0fThe 1986 BEFORECOLTJMBUS FOTJNDATION AMERICANBOOK THIS BRIDGE CALLED MY BACK WRITINGS BY RADICAL WOMEN OF COLOR EDITORS: _ CHERRIE MORAGA GLORIA ANZALDUA FOREWORD: TONI CADE BAMBARA KITCHEN TABLE: Women of Color Press a New York Copyright © 198 L 1983 by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. Published in the United States by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Post Office Box 908, Latham, New York 12110-0908. Originally published by Peresphone Press, Inc. Watertown, Massachusetts, 1981. Also by Cherrie Moraga Cuentos: Stories by Latinas, ed. with Alma Gomez and Mariana Romo-Carmona. Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983. Loving in the War Years: Lo Que Nunca Paso Por Sus Labios. South End Press, 1983. Cover and text illustrations by Johnetta Tinker. Cover design by Maria von Brincken. Text design by Pat McGloin. Typeset in Garth Graphic by Serif & Sans, Inc., Boston, Mass. Second Edition Typeset by Susan L. -

Cultivating the Daughters of Bilitis Lesbian Identity, 1955-1975

“WHAT A GORGEOUS DYKE!”: CULTIVATING THE DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS LESBIAN IDENTITY, 1955-1975 By Mary S. DePeder A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Susan Myers-Shirk, Chair Dr. Kelly A. Kolar ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I began my master’s program rigidly opposed to writing a thesis. Who in their right mind would put themselves through such insanity, I often wondered when speaking with fellow graduate students pursuing such a goal. I realize now, that to commit to such a task, is to succumb to a wild obsession. After completing the paper assignment for my Historical Research and Writing class, I was in far too deep to ever turn back. In this section, I would like to extend my deepest thanks to the following individuals who followed me through this obsession and made sure I came out on the other side. First, I need to thank fellow history graduate student, Ricky Pugh, for his remarkable sleuthing skills in tracking down invaluable issues of The Ladder and Sisters. His assistance saved this project in more ways than I can list. Thank-you to my second reader, Dr. Kelly Kolar, whose sharp humor and unyielding encouragement assisted me not only through this thesis process, but throughout my entire graduate school experience. To Dr. Susan Myers- Shirk, who painstakingly wielded this project from its earliest stage as a paper for her Historical Research and Writing class to the final product it is now, I am eternally grateful. -

Professor Bonnie Zimmerman Vice-President for Faculty Affairs September 7, 2010 Interviewed by Susan Resnik for San Diego State

Professor Bonnie Zimmerman Vice-President for Faculty Affairs September 7, 2010 interviewed by Susan Resnik for San Diego State University 125:51 minutes of recording SUSAN RESNIK: Today is Tuesday, September 7, 2010. This Susan Resnik. I’m with Professor Bonnie Zimmerman in the offices of Special Collections and University Archives at San Diego State University. We’re going to conduct an oral history interview. This project is funded by the John and Jane Adams Grant for the Humanities. Professor Zimmerman retired this year from San Diego State University after a notable career in a variety of roles, beginning in 1978. From 2003 until this year, she was associate vice-president and led Faculty Affairs, having previously served as the chair of the university senate. She began as a lecturer in women’s studies in 1978, and became an associate professor of women’s studies from 1980 through ’83. In 1983 she became a professor. She taught courses, chaired theses, contributed to the syllabus, served as the chair of women’s studies from 1986 to 1992, and again from 1995 to 1997. For more than thirty years, through her research, teaching, and program development, she has fostered the growth of women and lesbian studies. She’s been an active member of the Modern Language Association and the National Women’s Studies Association, of which she served as president in 1998 and 1999. She has published extensively, including her books, Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia; The New Lesbian Studies: Into the 21st Century; Professions of Desire; Lesbian and Gay Studies in Literature; and the Safe Sea of Women: Lesbian Fiction, 1969 to 1989. -

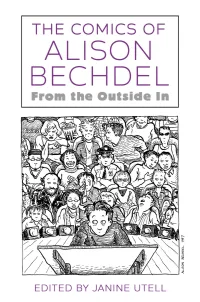

The Comics of Alison Bechdel from the Outside In

The Comics of Alison Bechdel From the Outside In Edited by Janine Utell University Press of Mississippi / Jackson CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX THE WORKS OF ALISON BECHDEL XI INTRODUCTION Serializing the Self in the Space between Life and Art JANINE UTELL XIII I. IN AND/OR OUT: QUEER THEORY, LESBIAN COMICS, AND THE MAINSTREAM THE HOSPITABLE AESTHETICS OF ALISON BECHDEL VANESSA LAUBER 3 “GIRLIE MAN, MANLY GIRL, IT’S ALL THE SAME TO ME” How Dykes to Watch Out For Shifted Gender and Comix ANNE N. THALHEIMER 22 DISSEMINATING QUEER THEORY Dykes to Watch Out For and the Transmission of Theoretical Thought KATHERINE PARKER-HAY 36 BECHDEL’S MEN AND MASCULINITY Gay Pedant and Lesbian Man JUDITH KEGAN GARDINER 52 VI CONTENTS MO VAN PELT Dykes to Watch Out For and Peanuts MICHELLE ANN ABATE 68 II. INTERIORS: FAMILY, SUBJECTIVITY, MEMORY DANCING WITH MEMORY IN FUN HOME ALISSA S. BOURBONNAIS 89 “IT BOTH IS AND ISN’T MY LIFE” Autobiography, Adaptation, and Emotion in Fun Home, the Musical LEAH ANDERST 105 GENERATIONAL TRAUMA AND THE CRISIS OF APRÈS-COUP IN ALISON BECHDEL’S GRAPHIC MEMOIRS NATALJA CHESTOPALOVA 119 THE EXPERIMENTAL INTERIORS OF ALISON BECHDEL’S ARE YOU MY MOTHER? YETTA HOWARD 135 INCHOATE KINSHIP Psychoanalytic Narrative and Queer Relationality in Are You My Mother? TYLER BRADWAY 148 III. PLACE, SPACE, AND COMMUNITY DECOLONIZING RURAL SPACE IN ALISON BECHDEL’S FUN HOME KATIE HOGAN 167 FUN HOME AND ARE YOU MY MOTHER? AS AUTOTOPOGRAPHY Queer Orientations and the Politics of Location KATHERINE KELP-STEBBINS 181 CONTENTS VII INSIDE THE ARCHIVES OF FUN HOME SUSAN R. -

Written Out: How Sexuality Is Used to Attack Women's Organizing

REVISED AND UPDATED A Report of the and the International Gay and Lesbian Center for Women’s Human Rights Commission Global Leadership written out how sexuality is used to attack women’s organizing Written and researched by Cynthia Rothschild Edited and with contributions by Scott Long and Susana T. Fried A revised publication of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) and the Center for Women's Global Leadership (CWGL) International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission table of contents The mission of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) is to secure the full enjoyment of the human rights of all people and communities subject to discrimination or abuse on the basis of sexual orientation or expression, gender identity or expression, and/or HIV sta- Preface to 2005 Edition . .1 tus. A US-based non-profit, non-governmental organization (NGO), IGLHRC effects this mission Introduction . .3 through advocacy, documentation, coalition building, public education, and technical assistance. I “How Can There Be Names For What Does Not Exist?” . .25 International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission The Target: Women’s Organizing, Women’s Bodies . .25 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor Sexual Rights . .35 New York, New York 10118 USA Tel: 212-216-1814 Basics of Baiting: Internationalizing Intolerance . .41 Fax: 212-216-1876 The Effects: Internalizing Fear . .53 [email protected] http://www.iglhrc.org II Women Make Cookies: Discrediting of Women Leaders . .65 III “We Would Have a Hard Time Going Home”: Fear of Sexuality in the International Sphere” . .83 Center for Women’s Global Leadership The Center for Women’s Global Leadership (Global Center) develops and facilitates women’s leader- Beijing: The Right Wing Takes on Human Rights . -

SARAH WATERS's TIPPING the VELVET* María Isabel Romero Ruiz

PROSTITUTION, IDENTITY AND THE NEO-VICTORIAN: SARAH WATERS’S TIPPING THE VELVET* María Isabel Romero Ruiz Universidad de Málaga Abstract Sarah Waters’s Neo-Victorian novel Tipping the Velvet (1998) is set in the last decades of the nineteenth century and its two lesbian protagonists are given voice as the marginalised and “the other.” Judith Butler’s notion of gender performance is taken to its extremes in a story where male prostitution is exerted by a lesbian woman who behaves and dresses like a man. Therefore, drawing from Butler’s theories on gender performance and Elisabeth Grosz’s idea about bodily inscriptions, this article will address Victorian and contemporary discourses connected with the notions of identity and agency as the result of sexual violence and gender abuse. Keywords: violence, prostitution, Tipping the Velvet, bodily inscriptions, performance, Judith Butler, Elisabeth Grosz. Resumen La novela neo-victoriana de Sarah Waters Tipping the Velvet (1998) está situada en las últi- mas décadas del siglo xix y sus dos protagonistas lesbianas reciben voz como marginadas y «las otras». La noción de performatividad de género de Judith Butler es llevada hasta los 187 extremos en una historia donde la prostitución masculina es ejercida por una mujer lesbiana que se comporta y se viste como un hombre. Por tanto, utilizando las teorías de Butler sobre la performatividad del género y la idea de Elisabeth Grosz sobre inscripciones corpóreas, este artículo tratará de acercarse a discursos victorianos y contemporáneos relacionados con las nociones de identidad y agencialidad como resultado de la violencia sexual y el abuso de género. -

Feminism, Pornography and Ethical Heterosex Katherine Albury Phd, School of Media, Film and Theatre 2006

Impure Relations: Feminism, Pornography and Ethical Heterosex Katherine Albury PhD, School of Media, Film and Theatre 2006 ABSTRACT This thesis engages with feminist and queer theory to assert that heterosexuality can be understood not as a fixed, unchanging and oppressive institution, but as changing combination of erotic and social affects which coexist within public and private bodies, discourses and imaginations. Drawing on the work on Michel Foucault, William Connolly, Eve Sedgwick and others, it examines the multiple discourses of heterosexuality that are already circulating in popular culture, specifically, representations of sex and gender within sexually explicit media. It examines the fields of polyamory, ‘feminist porn’, amateur and DIY pornography and ‘taboo’ sexual practices to demonstrate the possibilities offered by non-normative readings of heterosex. These readings open up space not only for queerer, less oppressive heterosexualities, but also for models of ethical sexual learning which incorporate heterosexual eroticism and emphasise both the pleasures and dangers of heterosex. Keywords: Heterosexuality, Pornography, Sexual Ethics, Feminism 1 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Albury First name: Katherine Other name/s: Margaret Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: margaret School: SAM (previously EMPA) Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: Impure relations: Feminism, pornography and ethical heterosex Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis engages with feminist and queer theory to assert that heterosexuality can be understood not as a fixed, unchanging and oppressive institution, but as changing combination of erotic and social affects which coexist within public and private bodies, discourses and imaginations. -

Guidance for Football Governing Bodies on Lgbt Inclusion and the Prevention of Discrimination and Violence Impressum

PRIDE IN SPORT Preventing and fighting homophobic violence and discriminations in sport GUIDANCE FOR FOOTBALL GOVERNING BODIES ON LGBT INCLUSION AND THE PREVENTION OF DISCRIMINATION AND VIOLENCE IMPRESSUM Guidance for Football Governing Bodies on LGBT Inclusion and the Prevention of Discrimination and Violence Publisher and Copyright: European Gay & Lesbian Sport Federation (EGLSF) Author: Megan Worthing-Davies Contributor: Juliette Jacques Design: Jen Watts Design Printed: 2013 in Ljubljana, Slovenia 150 copies Funded by: European Commission ISBN: 978-90-820842-0-7 This publication is free of charge. Disclaimer: The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the authors. The content of this publication may be freely reproduced and modified for non-commercial purposes under Creative Commons Licence Attribution- NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (acknowledging the author and listing the source). More information: www.prideinsport.info CONTENTS 1 WHAT ARE THE ISSUES? (6) • What do the terms lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans or transgender mean? (7) • How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT)? (7) • What is homophobia, lesbophobia, biphobia and transphobia? (8) • How does discrimination affect LGBT people and their participation in sport? (9) • A framework for addressing homophobia, lesbophobia, biphobia and transphobia in football (11) 2 TAKING ACTION (20) • A framework for addressing homophobia, -

Critical Activism – Five Conditions for a Beneficial, Effective and Efficient Activism

Linköping University | Department of Culture and Communication Master’s Thesis, 15 ECTS Credits | Applied Ethics Spring Semester 2019 | LIU-CTE-AE-EX--19/10--SE Critical Activism – Five Conditions for a Beneficial, Effective and Efficient Activism Tatiana Oviedo Ramos Supervisor: Lars Lindblom Examiner: Elin Palm Linköping University SE-581 83 Linköping +46 13 28 10 00, www.liu.se Acknowledgments To Noemí for trusting on this project, to Lars for showing interest, a tantas personas bellas, to my parents. 1 Abstract The goal of this thesis is to introduce the concept of Critical Activism (CA). Activism is expected to be beneficial and efficient. Therefore, there is a need of guiding conditions. To this end, I analyse a critical Pride movement, which arises as a reaction to the existing Pride movement, in such context. It is concluded that a CA must be political, radical, comprehensive, quotidian and inclusive. These five conditions help an activism to be beneficial and efficient. Keywords: Activism, Critical Activism, Orgullo Crítico, Pride, Madrid Pride, MADO 2 Content Acknowledgments ............................................................................................. 1 ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 2: STUDY CASE – THE MADRID PRIDE.................................... 6 CHAPTER 3: CONDITIONS FOR CRITICAL ACTIVISM ............................