Hist Studies Vol 77 (Anglais)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venerable Alfred Pampalon, C.Ss.R. (1867–1896)

Venerable Alfred Pampalon, C.Ss.R. (1867–1896) Alfred Pampalon was born on November 24, 1867, in Lévis (Quebec), the ninth of twelve children. His father was a builder and contractor, who worked building churches. After attending primary school for two years, Alfred enters the Collège de Lévis, in 1876, where he takes courses in business. Five years later, after an illness, he begins classical studies in order to become a priest. Shortly before his sixth year, in 1885, he contracts pneumonia. They thought he was going to die. Following his recovery, that was attributed to the intercession of Saint Anne, Alfred sets out on a pilgrimage, by foot, to the shrine of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré to give thanks for his healing. Here, on this occasion, he asks to enter the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer of which his brother was already a member. He is accepted and in July 1886 he sails off for the Redemptorist novitiate in Saint-Trond, Belgium. On September 8, 1887, he takes his perpetual vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Given the precarious state of his health, the superiors had been reluctant to receive him into the community, but his exemplary piety outweighed all objection. After completing his studies in Philosophy and Theology, he is ordained priest on October 4, 1892. The following year, on August 31, he is appointed to the monastery in Mons, where he carries out various duties, replacing absent priests or on occasion accompanying those who go to preach in neighboring parishes. From April to September 1894 he undertakes a second novitiate at Beau Plateau, which among the Redemptorists served as a preparation for conducting missions and parish retreats. -

Saint Joseph De Clairval Abbey Newsletter (Free of Charge), Contact the Abbey

Saint Joseph de ClaiNewsletterrval ofA Aprilbbe 17, 2010,y Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Dears Friends, MONG the perils today that threaten youth and all of society, drugs are “ among the most dangerous, and all the more insidious since they are less visible... In the early stages of drug abuse, the user often holds an attitudeA of skepticism toward others and towards religion, marked by hedonism, which in the end leads to frustration, existential emptiness, a belief in the futili- ty of life, and a drastic deterioration... The scourge of drugs, encouraged by large economic and sometimes also political interests, has spread throughout the entire world,” declared Pope John Paul II (May 27, 1984 and June 24, 1991). On May 14, 1991, the same Pontiff declared the heroic virtues of a young Redemptorist religious, Father Alfred Pampalon, who, since his blessed death in 1896, is often invoked by alcohol and drug addicts. The apparently insignificant life of this man shines like a light for our era, greedy for material efficiency and comfort. He built his life on supernatural realities, and what abundant favors— even temporal ones—have been obtained through his intercession ! Venerable Alfred Pampalon All rights reserved On November 24, 1867, Alfred was born in the Marian parish of Notre-Dame de Lévis in Quebec, the ninth child in a deeply Christian family. His father, One year later, Monsieur Pampalon decided to Antoine Pampalon, was a contractor who built church- remarry. He married a fine Irish widow, Margaret Phelan, who would regard all of Antoine’s children as es. His mother, Josephine Dorion, known for her humil- her own. -

Saints and Blessed People

Saints and Blessed People Catalog Number Title Author B Augustine Tolton Father Tolton : From Slave to Priest Hemesath, Caroline B Barat K559 Madeleine Sophie Barat : A Life Kilroy, Phil B Barbarigo, Cardinal Mark Ant Cardinal Mark Anthony Barbarigo Rocca, Mafaldina B Benedict XVI, Pope Pope Benedict XVI , A Biography Allen, John B Benedict XVI, Pope My Brother the Pope Ratzinger, Georg B Brown It is I Who Have Chosen You Brown, Judie B Brown Not My Will But Thine : An Autobiography Brown, Judie B Buckley Nearer, My God : An Autobiography of Faith Buckley Jr., William F. B Calloway C163 No Turning Back, A Witness to Mercy Calloway, Donald B Casey O233 Story of Solanus Casey Odell, Catherine B Chesterton G. K. C5258 G. K. Chesterton : Orthodoxy Chesterton, G. K. B Connelly W122 Case of Cornelia Connelly, The Wadham, Juliana B Cony M3373 Under Angel's Wings Maria Antonia, Sr. B Cooke G8744 Cooke, Terence Cardinal : Thy Will Be Done Groeschel, Benedict & Weber, B Day C6938 Dorothy Day : A Radical Devotion Coles, Robert B Day D2736 Long Loneliness, The Day, Dorothy B de Foucauld A6297 Charles de Foucauld (Charles of Jesus) Antier, Jean‐Jacques B de Oliveira M4297 Crusader of the 20th Century, The : Plinio Correa de Oliveira Mattei, Riberto B Doherty Tumbleweed : A Biography Doherty, Eddie B Dolores Hart Ear of the Heart :An Actress' Journey from Hollywood to Holy Hart, Mother Dolores B Fr. Peter Rookey P Father Peter Rookey : Man of Miracles Parsons, Heather B Fr.Peyton A756 Man of Faith, A : Fr. Patrick Peyton Arnold, Jeanne Gosselin B Francis F7938 Francis : Family Man Suffers Passion of Jesus Fox, Fr. -

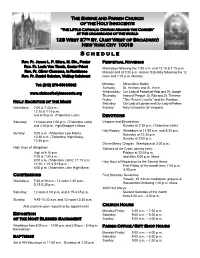

Schedule Rev

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Founded 1866 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Monday: Miraculous Medal Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Thérèse Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Devotions Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Vespers and Benediction: and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Saturday at 12:35 p.m. 10:30 a.m. (Tridentine High Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. 12:30 p.m. Divine Mercy Chaplet: Weekdays at 3:00 p.m. -

January 1828 and Was Ordained Priest in Fribourg on 13Th June 1829

270. A Dictionary January 1828 and was ordained priest in Fribourg on 13th June 1829. From 1848 to 1851 he was superior of the Swiss province, called after 1850 that of France and Switzerland. Shortly after his term of office he was transferred to the Belgian province, where his missions, especially in the diocese of Tournai, revealed his extraordinary prowess as a preacher. For a time he was novice master in St. Trond. He died in Luxemburg on 29th January 1881. BIBLIOGRAPHY: SH, 12 (1964) 25; 13 (1965) 283; MA, 59; ·BG, Ill, 361. OUR LADY OF PERPETUAL HELP AND ST. ALPHONSUS Archconfraternity of The confraternity, whose aim is to propagate devotion to Our Lady of Perpetual Help, was erected on 25th May 1871 in the church of Sant'Alfonso, Rome, by Cardinal Costantino Patrizi, Vicar General of Rome. The miraculous picture had been exposed for veneration in the same church some five years earlier. Pius IX conferred the dignity of archconfraternity on 31st August 1876. The supreme moderator is the Superior General of the Redemptorists. BIBLIOGRAPHY: . Seraphinus de Angelis, De fidelium associationibus, 11, Rome, 1959, 161-163. PACIFIC Vice-province of Was also called for a time the vice-province of South America. The two foundations made in Ecuador in 1870 were placed under the care of Father Jean-Pierre Didier, who was given the title of Visitor. \Vith the erection of the provinces of Lyons and Paris in 1900 the South American foundations were also divided. The Southern vice province of the Pacific came under the jurisdiction of the Lyons prov ince and the Northern under that of Paris. -

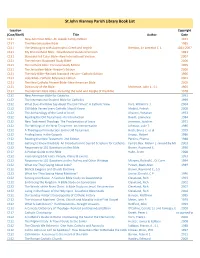

St John Vianney Parish Library Book List

St John Vianney Parish Library Book List Location Copyright (Case/Shelf) Title Author Date C1S1 New American Bible--St. Jospeh Family Edition 1971 C1S1 The New Jerusalem Bible 1985 C1S1 The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English Brenton, Sir Lancelot C. L. 1851-2007 C1S1 My First Catholic Bible--New Revised Standard Version 1993 C1S1 Standard Full Color Bible--New International Version 2007 C1S1 The Holman Illustrated Study Bible 2006 C1S1 The Catholic Bible Personal Study Edition 1995 C1S1 The Jerusalem Bible--Reader's Edition 2000 C1S1 The Holy Bible--Revised Standard Version--Catholic Edition 1966 C1S1 Holy Bible--Catholic Reference Edition 2001 C1S1 The New Catholic Answer Bible--New American Bible 2005 C1S1 Dictionary of the Bible McKenzie, John L., S.J. 1965 C1S1 The Holman Bible Atlas--Including the Land and People of the Bible 1978 C1S2 New American Bible for Catholics 1991 C1S2 The International Student Bible for Catholics 1999 C1S2 What Does the Bible Say About the End Times? A Catholic View Kurz, William S. J. 2004 C1S2 150 Bible Verses Every Catholic Should Know Madrid, Patrick 2008 C1S2 The Archaeology of the Land of Israel Aharoni, Yohanan 1973 C1S2 Reading the Old Testament--An Introduction Boadt, Lawrence 1984 C1S2 New Testament Theology The Proclamation of Jesus Jeremias, Joachim 1971 C1S2 The Writings of the New Testament An Interpretation Johnson, Luke T. 1986 C1S2 A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament Birch, Bruce C. et al. 1999 C1S2 Finding Jesus in the Gospels Knopp, Robert 1986 C1S2 Reading the New Testament 2nd Edition Perkins, Pheme 1988 C1S2 Getting to Know the Bible An Introduction to Sacred Scripture for Catholics Farrell, Rev. -

Fonds Lionel Saint-Georges Lindsay (CL08)

Secteur des archives privées de la Ville de Lévis Finding Aid - Fonds Lionel Saint-Georges Lindsay (CL08) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: August 30, 2018 Language of description: French Secteur des archives privées de la Ville de Lévis Bibliothèque Saint-David 4 rue Raymond-Blais Lévis Québec Canada G6W 6N3 Telephone: 418-835-4960, poste 8851 Email: [email protected] http://archiveshistoriques.ville.levis.qc.ca/index.php/fonds-lionel-saint-georges-lindsay Fonds Lionel Saint-Georges Lindsay Table of contents Summary information .................................................................................................................................... 16 Administrative history / Biographical sketch ................................................................................................ 16 Scope and content ......................................................................................................................................... 17 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................. 17 Notes .............................................................................................................................................................. 17 Access points ................................................................................................................................................. 18 Collection holdings ....................................................................................................................................... -

The Redemptorists

Sixth Sunday of Easter May 10, 2015 Staffed by From the Rector Very Rev. Raymond Collins, C.Ss.R. The Redemptorists Today is Mothers’ Day and so we celebrate all those who have given life to each one of us in such a miraculous way. There is no Weekday Masses more complete living out of the Paschal Mystery than in moth- 7:00am and 12:10pm erhood. The life they have given each one of us is celebrated especially when we hear the Lord announce the greatest com- Saturday Masses mandment: love one another as I have loved you. 8:00am and 12:10pm On this Mothers’ Day, I think a few thoughts…I think first of all of the many couples who truly desire to have children but are unable to do so. St. Gerard Majella, a Redemptorist Sunday Masses saint, is not only the patron saint of mothers, but also intercedes for couples who wish Saturday Vigil 4:00pm to conceive. On this day, our parish reaches out to these couples and we pray with you. 9:00am,11:00am (Spanish),12:30pm,5:00pm On this Mothers’ Day…I pray for those who feel there is not much to celebrate this day Sacrament of Penance because their life experience with their own mother has not been very positive. Human Monday-Saturday at 11:50am relationships are so often difficult and it takes so much for one to work. Saturday 3:30pm On this Mothers’ Day…I think of my own mother, Margaret (Greene) Collins. Like many Wednesday Novena Service young people her age, Mom left her homeland of Ireland in the mid 1920’s. -

Living Redemptorist Spirituality

Living Redemptorist Spirituality Pr ayers, Devotions, Reflections PARTNERSHIP IN MISSION REDEMPTORIST CONFERENCE OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright 2018 © Redemptorists, North America CONTENTS ISBN 978-0-7648-2810-2 Introduction 4 First Published 2009. Revised in 2018 SECTION ONE Scripture translations are from the New American Bible. ST. ALPHONSUS LIGUORI AND PRAYER 9 Psalm texts © The Grail (England) 1963. SECTION TWO REDEMPTORIST DEVOTION TO MARY 21 All rights reserved. No part of Living Redemptorist Spirituality may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, SECTION THREE recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in REDEMPTORIST SAINTS 28 printed reviews, without the prior written permission of the Redemptorists of North America, Partnership in Mission. SECTION FOUR For more information about the Redemptorists, visit cssr.net OTHER WAYS TO PRAY 66 Conclusion 76 Prayer for Vocations to the Redemptorist Family 78 For more information about Calendar 79 Redemptorist Partnership in Mission, send an email to [email protected] In recent years, Redemptorists have come to a re- newed and deeper understanding of the Church as the communion of believers, entrusted with carrying on the redeeming mission of Jesus. The Church is the people of God, embracing all the baptized and inviting Introduction all to share in its evangelizing mission. So Redemptor- Copiosa apud eum redemptio ists have been seeking ways to involve others—lay- people especially—in their part of that mission of Je- (With the Lord, there is plentiful redemption) sus and the Church. In North America, desire has grown among lay- Those words from Psalm 130 are the motto of the Con- people to share in both the spirituality and the mis- gregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (the Redemp- sion of Redemptorists. -

Six Churches, One Vibrant Catholic Community

Six Churches, One Vibrant Catholic Community Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland Most Reverend Robert P. Deeley, J.C.D., Bishop Our Parishes Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception 307 Congress Street Sacred Heart/Saint Dominic Parish 65 Mellen Street Saint Christopher Parish 15 Central Avenue Peaks Island Our Lady Star of the Sea 8 Beach Avenue Long Island Saint Louis Parish 279 Danforth Street Saint Peter's Parish 72 Federal Street Website: www.portlandcatholic.org Email: [email protected] Administrative Offices Very Reverend Gregory P. Dube Rector & Pastor Catholic Pastoral Center at Guild Hall 307 Congress St. Portland, Maine 04101 9am1pmMondayFriday 2077737746 Cluster Mission Statement We, the people of the Portland Peninsula and Island Parishes, are a diverse and multicultural community of Roman Catholics seeking to draw ourselves and others into deeper union with God through the cele- bration of the Sacraments, the proclamation of the Gospel, and service to our neighbor. We welcome all to share in the beauty of our Catholic faith and traditions as we strive to witness the love of Jesus Christ present among us. PASTORAL CORNER NOVEMBER 9 & 10, 2019 Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception’s 150th Anniversary Reception to Benefit St. Vincent de Paul Soup Kitchen on December 7 The Portland Peninsula & Island Parishes will host the 150th Anniversary Reception for the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Portland on Satur- day, December 7, the eve of the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception. Following a 4 p.m. Mass celebrated by Bishop Robert P. Deeley, the recep- tion will be held in the cathedral’s Guild Hall at 5 p.m. -

Canadian Saints and Blesseds

THE CANADIAN SAINTS The Canadian Martyrs: Saint Isaac Jogues , Jesuit priest, (Born in 1608, martyred in 1646). Saint Jean de Brébeuf , Jesuit priest, (Born in 1593, martyred in 1649). Saint Charles Garnier , Jesuit priest, (Born in 1606, martyred in 1649). Saint Antoine Daniel , Jesuit priest, (Born in 1600, martyred in 1648). Saint Gabriel Lalemant , Jesuit priest, (Born in 1610, martyred in 1649). Saint Noel Chabanel , Jesuit priest, (Born in 1613, martyred in 1649). Saint René Goupil , Jesuit Novice, (Born in 1608, martyred in 1642). Saint Jean de La Lande , layperson, (Born in 160?, martyred in 1646). The eight Canadian Martyrs lived in Canada from 1625 to 1649. Canonized on June 29, 1930. Celebrated on September 26 in Canada. Feast celebrated on October 19 in the Universal Church. Other Canadian Saints... Saint Marguerite Bourgeoys (Born in 1620, died in 1700). Co-founded Montréal. Founder of the Congregation of Notre-Dame. Canonized on October 31, 1982. Feast celebrated on January 12. Saint Marguerite d'Youville (Born in 1701, died in 1771). Founder of the Sisters of Charity, known as the "Grey Nuns." Canonized in 1990. Feast celebrated on October 16. Saint André Grasset , Sulpician, (Born in 1758, died in 1792). Born in Montréal. Martyred in Paris on September 2, 1792 during the French Revolution. Beatified on October 17, 1926. Feast celebrated on September 2. Saint Brother André , (Born in 1845, died in 1937). (Also known as "Alfred Bessette") Brother of the religious Order of the Holy Cross. Built the Saint-Joseph Oratory of Mont-Royal at Montréal. Beatified on May 23, 1982. -

Missionaries of Africa - History Series, N° 2

Missionaries of Africa - History Series, n° 2. BISHOP JOHN FORBES (1864 - 1926) Coadjutor Vicar Apostolic of Uganda The First Canadian White Father Raynald Pelletier, M. Afr. Text Revised and Corrected by Jean-Claude Ceillier, M. Afr. Introduction The year 2001 was the centenary of the presence of the Missionaries of Africa in North America, and the occasion was marked by important celebrations in both Canada and the United States. It was an opportunity to look back over the past, to open archives, and to remember the personalities who figured in these hundred years of missionary presence and service. Among these personalities John Forbes was one of the most important. He was the Founder of the Province of the White Fathers in North America, and later became coadjutor Vicar Apostolic in Uganda. He was the first Canadian Missionary of Africa and the first North American to enter this missionary Society, founded in 1868 in Algiers by Archbishop Charles Lavigerie for the evangelization of Africa. John Forbes’ rich personality and several exceptional features in his missionary life make him a particularly attractive figure. He was a man totally available for any service, he had remarkable gifts as an organizer, a deep commitment to the Mission, a spirituality marked by an unquenchable optimism: these characteristics of John Forbes can still inspire us today and provide us with material for reflection. Within the context of this Historical Series, it seemed useful to present, among other projected subjects, the origin of the presence and missionary commitment of North American Fathers and Brothers in the history of the Society.