Space for "Quality": Negotiating with the Daleks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

The Future of The

The Future of Public Service Broadcasting Some thoughts Stephen Fry Before I can even think to presume to dare to begin to expatiate on what sort of an organism I think the British Broadcasting Corporation should be, where I think the BBC should be going, how I think it and other British networks should be funded, what sort of programmes it should make, develop and screen and what range of pastries should be made available in its cafés and how much to the last penny it should pay its talent, before any of that, I ought I think in justice to run around the games field a couple of times puffing out a kind of “The BBC and Me” mini‐biography, for like many of my age, weight and shoe size, the BBC is deeply stitched into my being and it is important for me as well as for you, to understand just how much. Only then can we judge the sense, value or otherwise of my thoughts. It all began with sitting under my mother’s chair aged two as she (teaching history at the time) marked essays. It was then that the Archers theme tune first penetrated my brain, never to leave. The voices of Franklin Engelman going Down Your Way, the women of the Petticoat Line, the panellists of Twenty Questions, Many A Slip, My Word and My Music, all these solid middle class Radio 4 (or rather Home Service at first) personalities populated my world. As I visited other people’s houses and, aged seven by now, took my own solid state transistor radio off to boarding school with me, I was made aware of The Light Programme, now Radio 2, and Sparky’s Magic Piano, Puff the Magic Dragon and Nelly the Elephant, I also began a lifelong devotion to radio comedy as Round The Horne, The Clitheroe Kid, I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again, Just A Minute, The Men from The Ministry and Week Ending all made themselves known to me. -

1 2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15

2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15, 2019 3:00-3:15 KEYNOTE “The Fandom Hierarchy: Women of Color’s Fight For Visibility In Fandom Spaces” Tai Gooden Women of Color (WoC) have been fervent Doctor Who fans for several decades. However, the fandom often reflects societal hierarchies upheld by White privilege that result in ignoring and diminishing WoC’s opinions, contributions, and legitimate concerns about issues in terms of representation. Additionally, WoC and non-binary (NB) people of color’s voices are not centered as often in journalism, podcasting, and media formats nor convention panels as much as their White counterparts. This noticeable disparity has led to many WoC, even those who are deemed “important” in fandom spaces, to encounter racism, sexism, and, depending on the individual, homophobia and transphobia in a place that is supposed to have open availability to everyone. I can attest to this experience as someone who has a somewhat heightened level of visibility in fandom as a pop culture/entertainment writer who extensively covers Doctor Who. This presentation will examine women of color in the Doctor Who fandom in terms of their interactions with non-POC fans and difficulties obtaining opportunities in media, online, and at conventions. The show’s representation of fandom and the necessity for equity versus equality will also be discussed to craft a better understanding of how to tackle this pervasive issue. Other actionable solutions to encourage intersectionality in the fandom will be discussed including privileged people listening to WoC and non- binary people’s concerns/suggestions, respectfully interacting with them online and in person, recognizing and utilizing their privilege to encourage more inclusivity, standing in solidarity with them on critical issues, and lending their support to WoC creatives. -

Doctor Who Magazines

mmm * fim THE * No.48 ARCHITECTS JANUARY A MARVEL MONTHLY 30p ^ OF FEAR! x > VICTORIAN SIAIfc ENGLAND trembles v , BENEATH A PHOTO FEATURE SPECIAL FEATURES ARCHITECTS OF FEAR 16 IS DOCTOR WHO TOO FRIGHTENING FOR AN EARL Y EVENING TV AUDIENCE? DOCTOR WHO MONTHLY DOESN'T THINK SO. WE INVESTIAGE THE FEARSOME ASPECTS OF THE SERIES. MONSTER GALLERY 20 ASA COMPANION PIECE TO OUR ARCHITECTS OF FEAR FEATURE WE PRESENT A SPECIAL PICTORIAL FEATURE ON THE MONSTERS OF DOCTOR WHO. STATE OF DECAY 22 DOCTOR WHO MONTHLY LOOKS AT THE DOCTOR'S MOST RECENT ADVENTURE. [■i»if i»: i’.’i:>y *i:m-Ty ti1 •f T|.»> y\ OUR VERY OWN MYSTERY IN THE WAX MUSEUM. DOCTOR WHO MONTHLY WAS PRESENT THE DAY THREE TOM BAKERS CAME FA CE- TO-FA CE THE TALONS OF WENG CHIANG 32 Editor: Paul Neary A SPECIAL PHOTO FEATURE ON THE 1977 DOCTOR WHO STORY. Features Editor: Alan McKenzie SPECIAL CONVENTION PICTORIAL 36 Layout: Steve O'Leary MANY OF THE FOLK IN VOL VED IN THE PRODUCTION OF THE Art Assistance: Rahid Khan DOCTOR WHO TV SERIES DROPPED INTO THE MARVEL Consultant: Jeremy Bentham CONVENTION LAST OCTOBER. WE PRESENT A PHOTOGRAPHIC REPORT ON JUST SOME OF THE EVENTS. Gothscan 2006 COMIC STRIPS fVT’AV ■ ' s OF DEATH 7 THE CONCLUSION OF THIS EXCITING TALE PLUS THE SAD DEPAR¬ ftp « iBggBg isgBasaL.3 TURE OF SHARON. his month we have a bumper crop of special features for your delight and delectation. We have a double helping on the subject of fear which includes a study of the horror content - or should that be lack TOUCHDOWN thereof? Plus we will be taking a look at some of the fearsome monster foes that I ON DENAB-7 have met on my travels through time and space. -

{PDF EPUB} Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon by Malcolm Hulke Doctor Who and the Dinosaur Invasion

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon by Malcolm Hulke Doctor Who and the Dinosaur Invasion. The Doctor and Sarah arrive in London to find it deserted. The city has been evacuated as prehistoric monsters appear in the streets. While the Doctor works to discover who or what is bringing the dinosaurs to London, Sarah finds herself trapped on a spaceship that left Earth months ago travelling to a new world… Against the odds, the Doctor manages to trace the source of the dinosaurs. But will he and the Brigadier be in time to unmask the villains before Operation Golden Age changes the history of planet Earth and wipes out the whole of human civilisation? This novel is based on a Doctor Who story which was originally broadcast from 12 January–16 February 1974. Featuring the Third Doctor as played by Jon Pertwee with his companion Sarah Jane Smith and UNIT. Doctor Who: Invasion Earth! (Classic Novels Box Set) Terrance Dicks. Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who And The Sea-Devils. Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who and the Cave Monsters. Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who And The War Games. Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who And The Green Death. Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who And The Silurians (TV Soundtrack) Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who And The Dinosaur Invasion. Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who And The Doomsday Weapon. Malcolm Hulke. Doctor Who: The Faceless Ones (TV Soundtrack) David Ellis. Malcolm Hulke. DOCTOR WHO. 101 Books. Malcolm Hulke was a prolific and respected television writer from the 1950s until the 1970s. His writing credits included the early science fiction Pathfinders series, as well as The Avengers. -

Terrance DICKS a Tribute

Terrance DICKS A tribute FEATURING: Chris achilleos John levene John peel Gary russell And many more Terrance DICKS A tribute CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF 2019 Contributors: Adrian Salmon, Gary Russell, John Peel, John Levene, Nick Walters, Terry Cooper, Adrian Sherlock, Rick Cross, Chris Achilleos, George Ivanoff, James Middleditch, Jonathan Macho, David A McIntee, Tim Gambrell, Wink Taylor. The right of contributing authors/artists to be identified as the Author/Owner of the Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Editor: Shaun Russell Editorial: Will Rees Cover by Paul Cowan Published by Candy Jar Books Mackintosh House 136 Newport Road, Cardiff, CF24 1DJ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In Memory of Terrance Dicks 14th April 1935 – 29th August 2019 Adrian Salmon Gary Russell He was the first person I ever interviewed on stage at a convention. He was the first “famous” home phone number I was ever given. He was the first person to write to me when I became DWM editor to say congratulations. He was a friend, a fellow grumpy old git, we argued deliciously on a tour of Australian conventions on every panel about the Master/Missy thing. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Dr Who Pdf.Pdf

DOCTOR WHO - it's a question and a statement... Compiled by James Deacon [2013] http://aetw.org/omega.html DOCTOR WHO - it's a Question, and a Statement ... Every now and then, I read comments from Whovians about how the programme is called: "Doctor Who" - and how you shouldn't write the title as: "Dr. Who". Also, how the central character is called: "The Doctor", and should not be referred to as: "Doctor Who" (or "Dr. Who" for that matter) But of course, the Truth never quite that simple As the Evidence below will show... * * * * * * * http://aetw.org/omega.html THE PROGRAMME Yes, the programme is titled: "Doctor Who", but from the very beginning – in fact from before the beginning, the title has also been written as: “DR WHO”. From the BBC Archive Original 'treatment' (Proposal notes) for the 1963 series: Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/doctorwho/6403.shtml?page=1 http://aetw.org/omega.html And as to the central character ... Just as with the programme itself - from before the beginning, the central character has also been referred to as: "DR. WHO". [From the same original proposal document:] http://aetw.org/omega.html In the BBC's own 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 14 November 1963), both the programme and the central character are called: "Dr. Who" On page 7 of the BBC 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 21 November 1963) there is a short feature on the new programme: Again, the programme is titled: "DR. WHO" "In this series of adventures in space and time the title-role [i.e. -

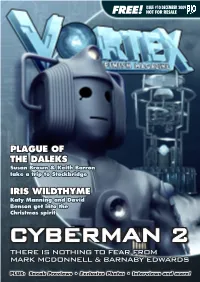

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Rich's Notes: the Ten Doctors: a Graphic Novel by Rich Morris 102

The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 102 Rich's Notes: Since the Daleks are struggling to destroy eachother as well as their attackers, the advantage goes to the Federation forces. Things are going well and the 5th Doctor checks in with the 3rd to see how the battle is playing out. The 3rd Doctor confirms that all is well so far, but then gets a new set of signals. A massive fleet of Sontaran ships unexpectedly comes out of nowhere, an the Sontaran reveal a plot to eliminate the Daleks, the Federation fleet AND the Time Lords! The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 103 Rich's Notes: The 3rd Doctor is restrained by the Sontarans before he can warn the fleet. The 5th Doctor tries as well, but the Master has jammed his signal. The Master explains how he plans to use his new, augmented Sontarans to take over the universe. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 104 Rich's Notes: Mistaking the Sontarans as surprise allies hoping to gain the lion’s share of the glory, the Draconian Ambassador and the Ice Warrior general move to greet them as befits their honour and station. But they get a nasty surprise when the Sontarans attack them. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 5 105 Rich's Notes: The Master, his plot revealed, now uses the sabotaged computer to take over control of the 5th Doctor’s ship. He uses it to torment his old enemy, but causing him to destroy the Federation allies. -

Sociopathetic Abscess Or Yawning Chasm? the Absent Postcolonial Transition In

Sociopathetic abscess or yawning chasm? The absent postcolonial transition in Doctor Who Lindy A Orthia The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract This paper explores discourses of colonialism, cosmopolitanism and postcolonialism in the long-running television series, Doctor Who. Doctor Who has frequently explored past colonial scenarios and has depicted cosmopolitan futures as multiracial and queer- positive, constructing a teleological model of human history. Yet postcolonial transition stages between the overthrow of colonialism and the instatement of cosmopolitan polities have received little attention within the program. This apparent ‘yawning chasm’ — this inability to acknowledge the material realities of an inequitable postcolonial world shaped by exploitative trade practices, diasporic trauma and racist discrimination — is whitewashed by the representation of past, present and future humanity as unchangingly diverse; literally fixed in happy demographic variety. Harmonious cosmopolitanism is thus presented as a non-negotiable fact of human inevitability, casting instances of racist oppression as unnatural blips. Under this construction, the postcolonial transition needs no explication, because to throw off colonialism’s chains is merely to revert to a more natural state of humanness, that is, cosmopolitanism. Only a few Doctor Who stories break with this model to deal with the ‘sociopathetic abscess’ that is real life postcolonial modernity. Key Words Doctor Who, cosmopolitanism, colonialism, postcolonialism, race, teleology, science fiction This is the submitted version of a paper that has been published with minor changes in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2): 207-225. 1 1. Introduction Zargo: In any society there is bound to be a division. The rulers and the ruled. -

Doctor Who: the Legends of River Song Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DOCTOR WHO: THE LEGENDS OF RIVER SONG PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jenny T. Colgan | 224 pages | 02 Jun 2016 | Ebury Publishing | 9781785940880 | English | London, United Kingdom Doctor Who: The Legends of River Song PDF Book The hosts and I disagreed on the other two stories, that were there favourites but not mine. By using this site, you agree to this use. Not you? A story that could only happen in Doctor Who which works brilliantly. Showing Trusted site. The idea with the captured Time Lord was a nice touch. This is a collection of five stories that follow the character River Song. For Whovians A great addition for any Dr Who library. I was intrigued with what was happening and it kept me wanting to know how it ended. Every word in this online book is packed in easy word to make the readers are easy to read this book. Whoever she really is, this archaeologist and time traveller has had more adventures and got into more trouble than most people in the universe. Single Digital Issue I thought this story was a lot of fun. She's such an elsive character and I love her flirty attitude and that she doesn't see herself short. Afterwards, the Doctor gives Mure a blunted sword that shoots tiny fireworks and Postumus keeps the emptied park open for the two of them alone, allowing them to have a picnic and enjoy the park's attractions. Well, when you re married to a Time Lord or possibly not , you have to keep track of what you did and when.