The Unbearable Heaviness of Philosophy Made Lighter, Fourth Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER Personality TEN Psychology

10/14/08 CHAPTER Personality TEN Psychology Psychology 370 Sheila K. Grant, Ph.D. SKINNER AND STAATS: Professor California State University, Northridge The Challenge of Behaviorism Chapter Overview Chapter Overview RADICAL BEHAVIORISM: SKINNER Part IV: The Learning Perspective PSYCHOLOGICAL BEHAVIORISM: STAATS Illustrative Biography: Tiger Woods Reinforcement Behavior as the Data for Scientific Study The Evolutionary Context of Operant Behavior Basic Behavioral Repertoires The Rate of Responding The Emotional-Motivational Repertoire Learning Principles The Language-Cognitive Repertoire Reinforcement: Increasing the Rate of Responding The Sensory-Motor Repertoire Punishment and Extinction: Decreasing the Rate of Situations Responding Additional Behavioral Techniques Psychological Adjustment Schedules of Reinforcement The Nature-Nurture Question from the Applications of Behavioral Techniques Perspective of Psychological Behaviorism Therapy Education Radical Behaviorism and Personality Theory: Some Concerns Chapter Overview Part IV: The Learning Perspective Personality Assessment from a Ivan Pavlov: Behavioral Perspective Heuristic Accendental Discovery The Act-Frequency Approach to Personality Classical Conditioning Measurement John B. Watson: Contributions of Behaviorism to Personality Theory and Measurement Early Behaviorist B. F. Skinner: Radical Behaviorism Arthur Staats: Psychological Behaviorism 1 10/14/08 Conditioning—the process of learning associations . Ivan Pavlov Classical Conditioning Operant Conditioning . 1849-1936 -

Pursuing Eudaimonia LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY STUDIES in ETHICS SERIES SERIES EDITOR: DR

Pursuing Eudaimonia LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY STUDIES IN ETHICS SERIES SERIES EDITOR: DR. DAVID TOREVELL SERIES DEPUTY EDITOR: DR. JACQUI MILLER VOLUME ONE: ENGAGING RELIGIOUS EDUCATION Editors: Joy Schmack, Matthew Thompson and David Torevell with Camilla Cole VOLUME TWO: RESERVOIRS OF HOPE: SUSTAINING SPIRITUALITY IN SCHOOL LEADERS Author: Alan Flintham VOLUME THREE: LITERATURE AND ETHICS: FROM THE GREEN KNIGHT TO THE DARK KNIGHT Editors: Steve Brie and William T. Rossiter VOLUME FOUR: POST-CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION Editor: Neil Ferguson VOLUME FIVE: FROM CRITIQUE TO ACTION: THE PRACTICAL ETHICS OF THE ORGANIZATIONAL WORLD Editors: David Weir and Nabil Sultan VOLUME SIX: A LIFE OF ETHICS AND PERFORMANCE Editors: John Matthews and David Torevell VOLUME SEVEN: PROFESSIONAL ETHICS: EDUCATION FOR A HUMANE SOCIETY Editors: Feng Su and Bart McGettrick VOLUME EIGHT: CATHOLIC EDUCATION: UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES, LOCALLY APPLIED Editor: Andrew B. Morris VOLUME NINE GENDERING CHRISTIAN ETHICS Editor: Jenny Daggers VOLUME TEN PURSUING EUDAIMONIA: RE-APPROPRIATING THE GREEK PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE CHRISTIAN APOPHATIC TRADITION Author: Brendan Cook Pursuing Eudaimonia: Re-appropriating the Greek Philosophical Foundations of the Christian Apophatic Tradition By Brendan Cook Pursuing Eudaimonia: Re-appropriating the Greek Philosophical Foundations of the Christian Apophatic Tradition, by Brendan Cook This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Brendan Cook All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

WAS SUMAROKOV a LOCKEAN SENSUALIST? on Locke's Reception in Eighteenth-Century Russia

Part One. Sumarokov and the Literary Process of His Time 8 WAS SUMAROKOV A LOCKEAN SENSUALIST? On Locke’s Reception in Eighteenth-Century Russia Despite the fact that Locke occupied a central place in European En- lightenment thought, his works were little known in Russia. Locke is often listed among those important seventeenth-century figures including Ba- con, Spinoza, Gassendi, and Hobbes, whose ideas formed the intellectual background for the Petrine reforms; Prokopovich, Kantemir, Tatishchev and perhaps Peter himself were acquainted with Locke’s ideas, but for most Russians in the eighteenth century Locke was little more than an illustrious name. Locke’s one book that did have a palpable impact was his Some Thoughts Concerning Education, translated by Nikolai Popovskii from a French version, published in 1759 and reprinted in 1788.1 His draft of a textbook on natural science was also translated, in 1774.2 Yet though Locke as pedagogue was popular, his reception in Russia, as Marc Raeff has noted, was overshadowed by the then current “infatuation with Rousseau’s pedagogical ideas.”3 To- ward the end of the century some of Locke’s philosophical ideas also held an attraction for Russian Sentimentalists, with their new interest in subjective 1 The edition of 1760 was merely the 1759 printing with a new title page (a so- called “titul’noe izdanie”). See the Svodnyi katalog russkli knigi grazhdanskoi pechati, 5 vols. (Мoscow: Gos. biblioteka SSSR imeni V. I. Lenina, 1962–674), II, 161–2, no. 3720. 2 Elements of Natural Philosophy, translated from the French as Pervonachal’nyia osno va niia fiziki (Svodnyi katalog, II, 62, no. -

A(Nthony) Charles Catania Curriculum Vitae August 2018

A(nthony) Charles Catania Curriculum Vitae August 2018 Date of Birth, New York, NY: 22 June 1936 Married: Constance Julia Britt, 10 February 1962 Children: William John, 3 February 1964 Kenneth Charles, 5 November 1965 Educational History P.S. 132, Manhattan; Bronx High School of Science, Class of 1953 A.B., Columbia College, 1957 New York State Regents Scholarship; Phi Beta Kappa; Highest Honors with Distinction in Psychology M.A., Columbia University, 1958 Ph.D. in Psychology, Harvard University, 1961 (March) National Science Foundation Fellow, 1958-60 Professional History Columbia College Teaching Assistant, 1956-58 Bell Telephone Laboratories Research Technician (under H. M. Jenkins), Summer 1958 Harvard University Research Fellow in Psychology (supported by B. F. Skinner’s NSF Grant), 1960-62 Smith Kline and French Laboratories Senior Pharmacologist (under L. Cook), 1962-64 University College of Arts and Science, New York University Assistant Professor, 1964-66; Associate Professor, 1966-69; Professor and Department Chair, 1969-73 University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) Professor, 1973-2008; Program Director/CoDirector, Applied Behavior Analysis MA track, 1998- 2007; Professor Emeritus, Departmental Curmudgeon, 2008- University of Wales (formerly University College of North Wales) Professorial Fellow and Fulbright Senior Research Fellow, 1986-87; Visiting Research Fellow, 1989- Keio University, Tokyo, Japan Visiting Professor, July 1992 Office: Department of Psychology (Emeritus Faculty office, Sondheim 012) University of -

Noumenon and Phenomenon: Reading on Kant's

NOUMENON AND PHENOMENON: READING ON KANT’S PROLEGOMENA Oleh: Wan Suhaimi Wan Abdullah1 ABSTRAK Makalah ini membahaskan satu dari isu besar yang diperkatakan oleh Kant dalam epistemologi beliau iaitu isu berkaitan ‘benda-pada-dirinya’ (noumenon) dan ‘penzahiran benda’ (phenomenon). Kaitan antara kewujudan kedua-dua hakikat ini dari segi ontologi dan kedudukan kedua-duanya dalam pengetahuan manusia dari segi epistemologi dibincangkan berdasarkan perspektif Kant. Semua ini dikupas berdasarkan penelitian terhadap suatu teks oleh Kant dalam karya agung beliau Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics That Will be Able to Present Itself as a Science. Kant secara umumnya tidak menolak kewujudan noumenon walaupun beliau seakan mengakui bahawa pendekatan sains sekarang tidak mampu menanggapi hakikat noumenon tersebut. Huraian makalah ini membuktikan bahawa tidak semua hakikat mampu dicapai oleh sains moden. Keyakinan bahawa sains moden adalah satu-satunya jalan mencapai ilmu dan makrifah akan menghalang manusia dari mengetahui banyak rahsia kewujudan yang jauh dari ruang jangkauan sains. 1 Wan Suhaimi Wan Abdullah, PhD. is an associate professor at the Department of `Aqidah and Islamic Thought, Academy of Islamic Studies, University of Malaya. Email: [email protected]. The author would like to thank Dr. Edward Omar Moad from Dept. of Humanities, Qatar University who have read the earlier draft of this article and suggested a very useful remarks and comments some of which were quoted in this article. Jurnal Usuluddin, Bil 27 [2008] 25-40 ABSTRACT The article discusses one of the major issues dealt with by Kant in his epistemology, that is the issue related to the thing-in-itself (noumenon) and the appearance (phenomenon). -

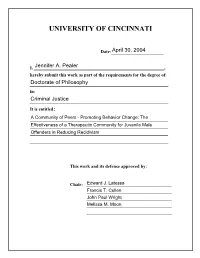

Complete Copy Pealer Dissertation

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A COMMUNITY OF PEERS – PROMOTING BEHAVIOR CHANGE: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF A THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY FOR JUVENILE MALE OFFENDERS IN REDUCING RECIDIVISM A Dissertation Submitted to the: Division of Research and Advance Studies Of the University of Cincinnati In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) In the Division of Criminal Justice Of the College of Education April 2004 by Jennifer A. Pealer, M.A. B.A., East Tennessee State University, 1997 M.A., East Tennessee State University, 1999 Dissertation Committee: Edward J. Latessa, Ph.D. (Chair) Francis T. Cullen, Ph.D. John Paul Wright, Ph.D. Melissa M. Moon, Ph.D. A COMMUNITY OF PEERS – PROMOTING BEHAVIOR CHANGE: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF A THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY FOR JUVENILE MALE OFFENDERS IN REDUCING RECIDIVISM One avenue that has received considerable attention for the substance abusing adult population is a therapeutic community; however, research examining the effectiveness of this popular treatment modality for juveniles is scarce. While some studies have found a reduction in criminal behavior and substance abuse, others have found null results concerning the effectiveness of therapeutic communities. Furthermore, the literature on therapeutic communities has been criticized on the following points: 1) studies fail to incorporate multiple outcome criteria to measure program success; 2) follow-up time frames have been inadequate; 3) comparison groups often fail to account for important differences between groups that are likely to impact program outcome; and 4) insufficient attention that is given to the measure of program quality. -

Philosophy As a Path to Happiness

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Philosophy as a Path to Happiness Attainment of Happiness in Arabic Peripatetic and Ismaili Philosophy Janne Mattila ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, University main building, on the 13th of June, 2011 at 12 o’clock. ISBN 978-952-92-9077-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-7001-3 (PDF) http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/ Helsinki University Print Helsinki 2011 2 Abstract The aim of this study is to explore the idea of philosophy as a path to happiness in medieval Arabic philosophy. The starting point is in comparison of two distinct currents within Arabic philosophy between the 10th and early 11th centuries, Peripatetic philosophy, represented by al-Fārābī and Ibn Sīnā, and Ismaili philosophy represented by al-Kirmānī and the Brethren of Purity. These two distinct groups of sources initially offer two contrasting views about philosophy. The attitude of the Peripatetic philosophers is rationalistic and secular in spirit, whereas for the Ismailis philosophy represents the esoteric truth behind revelation. Still, the two currents of thought converge in their view that the ultimate purpose of philosophy lies in its ability to lead man towards happiness. Moreover, they share a common concept of happiness as a contemplative ideal of human perfection, merged together with the Neoplatonic goal of the soul’s reascent to the spiritual world. Finally, for both happiness refers primarily to an otherworldly state thereby becoming a philosophical interpretation of the Quranic accounts of the afterlife. -

Beauty As a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2015 Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger John Jang University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jang, J. (2015). Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/112 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Philosophy and Theology Sydney Beauty as a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger Submitted by John Jang A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy Supervised by Dr. Renée Köhler-Ryan July 2015 © John Jang 2015 Table of Contents Abstract v Declaration of Authorship vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 Structure 3 Method 5 PART I - Metaphysical Beauty 7 1.1.1 The Integration of Philosophy and Theology 8 1.1.2 Ratzinger’s Response 11 1.2.1 Transcendental Participation 14 1.2.2 Transcendental Convertibility 18 1.2.3 Analogy of Being 25 PART II - Reason and Experience 28 2. -

Jamie Dornan: Shades of Desire Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JAMIE DORNAN: SHADES OF DESIRE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alice Montgomery | 256 pages | 01 Jan 2015 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780718180126 | English | London, United Kingdom Jamie Dornan: Shades of Desire PDF Book My wonderful wife awarnermusic has an EP out today. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Stacey Thomson rated it it was amazing May 20, Cancel Post Post. Overview The first, intimate biography of Jamie Dornan as he takes on one of the most iconic characters in fiction - Christian Grey. By Jen Kirby. A year later, four schoolfriends were killed in a car crash. Free delivery in the UK Read more here. About the Author Alice Montgomery is a freelance author living and working in London. How does his part as a BDSM-loving billionaire sit alongside his real life role as a family man and father to a young daughter? Publisher Penguin Books Ltd. In the interview, she spoke about having to use two very different accents in the two popular programmes. Our excellent value books literally don't cost the earth. Details if other :. Holy cow! The Latest. Priznavam, ze informace obsazene v tehle knizce pro me byly docela prekvapenim, protoze jsem o Jamiem Dornanovi nevedela pred jeho obsazenim do role Christiana Greye zhola nic. Jamie Dornan became a household name when he was cast in the Fifty Shades of Grey movie franchise in after Charlie Hunnam walked away from the role at the last minute. In this book we got insight into Jamie's childhood: view spoiler [ It just becomes sort of gratuitous if we don't need it. -

Hegel and Aristotle

This page intentionally left blank HEGEL AND ARISTOTLE Hegel is, arguably, the most difficult of all philosophers. To find a way through his thought, interpreters have usually approached him as though he were developing Kantian and Fichtean themes. This book is the first to demonstrate in a systematic way that it makes much more sense to view Hegel’s idealism in relation to the metaphysical and epis- temological tradition stemming from Aristotle. This book offers an account of Hegel’s idealism and in particular his notions of reason, subjectivity, and teleology, in light of Hegel’s inter- pretation, discussion, assimilation, and critique of Aristotle’s philoso- phy. It is the first systematic analysis comparing Hegelian and Aris- totelian views of system and history; being, metaphysics, logic, and truth; nature and subjectivity; spirit, knowledge, and self-knowledge; ethics and politics. In addition, Hegel’s conception of Aristotle’s phi- losophy is contrasted with alternative conceptions typical of his time and ours. No serious student of Hegel can afford to ignore this major new in- terpretation. Moreover, because it investigates with enormous erudi- tion the relation between two giants of the Western philosophical tra- dition, this book will speak to a wider community of readers in such fields as history of philosophy and history of Aristotelianism, meta- physics and logic, philosophy of nature, psychology, ethics, and politi- cal science. Alfredo Ferrarin is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Boston University. MODERN EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY General Editor Robert B. Pippin, University of Chicago Advisory Board Gary Gutting, University of Notre Dame Rolf-Peter Horstmann, Humboldt University, Berlin Mark Sacks, University of Essex This series contains a range of high-quality books on philosophers, top- ics, and schools of thought prominent in the Kantian and post-Kantian European tradition. -

A University Microfilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Neoplatonism: the Last Ten Years

The International Journal The International Journal of the of the Platonic Tradition 9 (2015) 205-220 Platonic Tradition brill.com/jpt Critical Notice ∵ Neoplatonism: The Last Ten Years The past decade or so has been an exciting time for scholarship on Neo platonism. I ought to know, because during my stint as the author of the “Book Notes” on Neoplatonism for the journal Phronesis, I read most of what was published in the field during this time. Having just handed the Book Notes over to George BoysStones, I thought it might be worthwhile to set down my overall impressions of the state of research into Neoplatonism. I cannot claim to have read all the books published on this topic in the last ten years, and I am here going to talk about certain themes and developments in the field rather than trying to list everything that has appeared. So if you are an admirer, or indeed author, of a book that goes unmentioned, please do not be affronted by this silence—it does not necessarily imply a negative judgment on my part. I hope that the survey will nonetheless be wideranging and comprehensive enough to be useful. I’ll start with an observation made by Richard Goulet,1 which I have been repeating to students ever since I read it. Goulet conducted a statistical analy sis of the philosophical literature preserved in the original Greek, and discov ered that almost threequarters of it (71%) was written by Neoplatonists and commentators on Aristotle. In a sense this should come as no surprise.