Speech by Mr Goh Chok Tong, Secretary-General of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee by Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S

4 Spotlight Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee By Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, the state funeral for Dr Goh Keng Swee that “Dr Goh was Dr Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his one of our nation’s founding fathers.… A whole generation speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth to be remembered. and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to The deepest recollections about Dr Goh must be the fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” personal memories of those who had the opportunity to How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Dr interact with him. At the core of these select few are Goh Keng Swee left a lasting impression on everyone he the members of his immediate and extended family. encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him and in his public career initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore. Our primary memories of Dr Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anti-colonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which Dr Goh played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Dr Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as “The Singapore Story”. -

The International History Bee and Bowl Asian Division Study Guide!

The International History Bee and Bowl Asian Division Study Guide Welcome to the International History Bee and Bowl Asian Division Study Guide! To make the Study Guide, we divided all of history into 5 chapters: Middle Eastern and South Asian History, East and Southeast Asian History, US American History, World History (everything but American and Asian) to 1789, and World History from 1789-present. There may also be specific questions about the history of each of the countries where we will hold tournaments. A list of terms to be familiar with for each country is included at the end of the guide, but in that section, just focus on the country where you will be competing at your regional tournament (at least until the Asian Championships). Terms that are in bold should be of particular focus for our middle school division, though high school competitors should be familiar with these too. This guide is not meant to be a complete compendium of what information may come up at a competition, but it should serve as a starting off point for your preparations. Certainly there are things that can be referenced at a tournament that are not in this guide, and not everything that is in this guide will come up. At the end of the content portion of the guide, some useful preparation tips are outlined as well. Finally, we may post additional study materials, sample questions, and guides to the website at www.ihbbasia.com over the course of the year. Should these become available, we will do our best to notify all interested schools. -

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and Post-Colonial Singapore Reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and post-colonial Singapore reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus by Sandra Hudd, B.A., B. Soc. Admin. School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, September 2015 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the Universityor any other institution, except by way of backgroundi nformationand duly acknowledged in the thesis, andto the best ofmy knowledgea nd beliefno material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text oft he thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. �s &>-pt· � r � 111 Authority of Access This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying fortwo years followingthe date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available forloan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. :3 £.12_pt- l� �-- IV Abstract By tracing the transformation of the site of the former Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, this thesis connects key issues and developments in the history of colonial and postcolonial Singapore. The convent, established in 1854 in central Singapore, is now the ‗premier lifestyle destination‘, CHIJMES. I show that the Sisters were early providers of social services and girls‘ education, with an orphanage, women‘s refuge and schools for girls. They survived the turbulent years of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and adapted to the priorities of the new government after independence, expanding to become the largest cloistered convent in Southeast Asia. -

Introduction 1. Literally, They Are Called Asia's Four Little Dragons. Some

Notes Introduction 1. Literally, they are called Asia's Four Little Dragons. Some prefer to call them Asia's Gang of Four. 2. This is particularly a view stressed by the theory of dependency, according to which colonialism has benefited the industrial countries in terms of the colony's supply of raw materials or cheap labour for the development of industries in the advanced countries. For a brief introduction of the concept, see Nicholas Abercombie, 1984, p. 65. 1 Social Background 1. In Singapore, considering that US$111 per month was the poverty line of the year 1976, the allowance of US$47.4 per household under the public assistance scheme was far below subsistence level (Heyzer, 1983, p. 119). In Hong Kong, most of those who receive public assistance have only about US$2 a day for their living expenses (HKAR, 1988, p. 150). Moreover, neither unemployment insurance nor the International Labour Organisation Convention (No. 102) on Social Security has been introduced. 2. The term 'caste', as suggested by Harumi Befu (1971, p. 121), refers to its 'class' frozen characteristics. Due to the limitation of stipends and the disposition of the Edo samurai to lead extravagant lives, the samurai faced considerable financial difficulties. These financial difficulties forced them to join in merchant activities and even to rely on the financial help of merchants. Thus more and more daimyo and samurai were in debt to merchants (see 1971, p. 122; Lehmann, 1982, pp. 70-1, 85). 3. The definitions of "art" is far wider in Japan than in the West. -

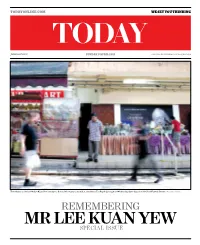

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

9789814677790 (.Pdf)

CONTRIBUTORS “Come to think of it, finally, it’s only friendship that matters.” Robert Kuok Lee Kuan Yew The idea for this book came about Yong Pung How in 2014. Liew Mun Leong and For ReviewUp Close Up only Close Othman Wok Ong Beng Seng were on a flight Puan Noor Aishah S.R. Nathan with back to Singapore and chatting J.Y. Pillay Up Close with about Mr Lee Kuan Yew, whom Lim Chin Beng they had known for many years. Wee Cho Yaw Lee Kuan Yew As they shared personal stories with Ch’ng Jit Koon Insights from colleagues and friends about their interactions with Sidek Saniff Lee Mr Lee, they felt it was time for Philip Yeo Lee Kuan Yew a book that told the personal side Jennie Chua Up Close with Lee Kuan Yew gathers some of the vivid about him. They broached the Liew Mun Leong memories of 37 people who have worked or interacted idea with Mr Lee on two separate Lim Siong Guan closely with Lee Kuan Yew in some way or other, from Jagjeet Singh dinner occasions; and when he when he was at Raffles College in 1941 right up to his Kuan Ng Kok Song gave his consent they formed demise in 2015. Among these are his 13 Principal Private Lam Chuan Leong a book committee comprising Secretaries and Special Assistants who lived and breathed Bilahari Kausikan Andrew Tan, Jennie Chua and Stephen Lee Mr Lee for a few years each, and Mdm Yeong Yoon Ying, Liew Mun Leong. Li Ka-shing his Press Secretary of over 20 years. -

The Loss of The'world-Soul'? Education, Culture and the Making

The Loss of the ‘World-Soul’? Education, Culture and the Making of the Singapore Developmental State, 1955 – 2004 by Yeow Tong Chia A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Yeow Tong Chia 2011 The Loss of the ‘World-Soul’? Education, Culture and the Making of the Singapore Developmental State, 1955 – 2004 Yeow Tong Chia Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of education in the formation of the Singapore developmental state, through a historical study of education for citizenship in Singapore (1955-2004), in which I explore the interconnections between changes in history, civics and social studies curricula, and the politics of nation-building. Building on existing scholarship on education and state formation, the dissertation goes beyond the conventional notion of seeing education as providing the skilled workforce for the economy, to mapping out cultural and ideological dimensions of the role of education in the developmental state. The story of state formation through citizenship education in Singapore is essentially the history of how Singapore’s developmental state managed crises (imagined, real or engineered), and how changes in history, civics and social studies curricula, served to legitimize the state, through educating and moulding the desired “good citizen” in the interest of nation building. Underpinning these changes has been the state’s use of cultural constructs such as ii Confucianism and Asian values to shore up its legitimacy. -

An Analysis of the Underlying Factors That Affected Malaysia-Singapore Relations During the Mahathir Era: Discords and Continuity

An Analysis of the Underlying Factors That Affected Malaysia-Singapore Relations During the Mahathir Era: Discords and Continuity Rusdi Omar Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Politics and International Studies School of History and Politics Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide May 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS i ABSTRACT v DECLARATION vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS ix GLOSSARY xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. Introductory Background 1 1.2. Statement of the Problem 3 1.3. Research Aims and Objectives 5 1.4. Scope and Limitation 6 1.5. Literature Review 7 1.6. Theoretical/ Conceptual Framework 17 1.7. Research Methodology 25 1.8. Significance of Study 26 1.9. Thesis Organization 27 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF MALAYSIA-SINGAPORE RELATIONS 30 2.1. Introduction 30 2.2. The Historical Background of Malaysia 32 2.3. The Historical Background of Singapore 34 2.4. The Period of British Colonial Rule 38 i 2.4.1. Malayan Union 40 2.4.2. Federation of Malaya 43 2.4.3. Independence for Malaya 45 2.4.4. Autonomy for Singapore 48 2.5. Singapore’s Inclusion in the Malaysian Federation (1963-1965) 51 2.6. The Period after Singapore’s Separation from Malaysia 60 2.6.1. Tunku Abdul Rahman’s Era 63 2.6.2 Tun Abdul Razak’s Era 68 2.6.3. Tun Hussein Onn’s Era 76 2.7. Conclusion 81 3 CONTENTIOUS ISSUES IN MALAYSIA-SINGAPORE RELATIONS 83 3.1. Introduction to the Issues Affecting Relations Between Malaysia and Singapore 83 3.2. -

Our Symbols, Our Spirit, Our Singapore

Our Symbols, Our Spirit, Our Singapore 1 “Honouring and respecting our symbols, however, is not something that is achieved only by legal regimes or protecting copyright; we must also cultivate and sustain the strong connection and respect that Singaporeans feel for symbols and songs. All of us have a part to play in upholding our symbols and passing them down to future generations.” Mr Edwin Tong Minister for Culture, Community and Youth and Second Minister for Law Response to Parliamentary Question on Safeguarding the use of our national symbols and national songs, 2021 2 04 A Cherished History, A National Identity How do we visually unite a young nation? 1959: National Flag 1959: National Anthem 1959: National Coat of Arms (State Crest) 1966: National Pledge 1981: National Flower 1986: Lion Head Symbol 1964: The Merlion 23 Through the Lens of Today Do our symbols mean the same to us? 32 The Future of Our Symbols Will Singapore need new national symbols? 38 Our Symbols, Our Spirit, Our Singapore 39 Acknowledgement A report by the Citizens’ Workgroup for National Symbols (2021) 3 A CHERISHED HISTORY, A NATIONAL IDENTITY "They were necessary symbols… since although we were not really independent in 1959 but self-governing, it was necessary right from the beginning that we should rally enough different races together as a Singapore nation." Dr Toh Chin Chye Former Deputy Prime Minister National Archives of Singapore, 1989 4 HOW DO WE VISUALLY UNITE A YOUNG NATION? From renewing our commitment by reciting the National Pledge, to singing the National Anthem, and hanging the National Flag approaching 9th August; How have the symbols of Singapore become familiar sights and sounds that make us wonder what it means to be a Singaporean? Our oldest national symbols were unveiled in 1959 before Singapore gained independence, and much has changed in Singapore since. -

The Fight for Women's Rights in Singapore

BIBLIOASIA OCT – DEC 2018 Vol. 14 / Issue 03 / Feature of Peace. They volunteered at feeding (Facing page) In the 1959 Legislative Assembly general election, the People’s Action Party was the only centres set up by the colonial government political party to campaign openly on the “one man one wife” slogan. As voting had become compulsory by for thousands of impoverished children then, women came out in full force on polling day. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy who were denied food and basic nutrition. of National Archives of Singapore. Others banded together to establish the (Below) War heroine Elizabeth Choy (in cheongsam) was the president of the Singapore Council of Women’s first family planning association in Sin- Protem Committee (1951–1952). As president, she helped to unite the diverse women groups in Singapore. Image reproduced from Lam, J.L., & Chew, P.G.L. (1993). Voices & Choices: The Women’s Movement in gapore, convinced that families should Singapore (p. 116). Singapore Council of Women’s Organisation and Singapore Baha’i Women’s Committee. have no more children than they could (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 VOI). feed, clothe and educate. Women recreated an identity for themselves by setting up alumni associa- tions (such as Nanyang Girls’ Alumni), recreational groups (Girls’ Sports Club) race-based groups (Kamala Club), reli- gious groups (Malay Women’s Welfare Association), housewives’ groups (Inner Wheel of the Rotary Club), professional groups (Singapore Nurses’ Association), national groups (Indonesian Ladies Club) and mutual help groups (Cantonese Women’s Mutual Help Association). One association, however, stood out amidst the post-war euphoria – the Singapore Council of Women (SCW). -

Press Release Statement from the Prime Minister's

1 PRESS RELEASE STATEMENT FROM THE PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE Dr. Toh Chin Chye, Deputy Prime Minister, has been offered the Vice-Chancellorship of the University of Singapore by the University Council when it met on the 6th March, 1968. The post has been vacant as a result of the death of the former Vice-Chancellor, Professor Lim Tay Boh. At an informal meeting on 7th March with members of the Senate of the University, the Prime Minister informed them that he intended to release Dr. Toh from his present ministerial duties, so that he can take up this appointment as Vice-Chancellor. However, Dr. Toh will remain a member of the Cabinet as Minister for Science and Technology. His ministerial staff will be with him at the office of the Vice-Chancellor in the University. His duties will be to co-ordinate development of the University of Singapore, the University of Nanyang, the Polytechnic, and later the Ngee Ann Community College. lky\1968\lky0309.doc 2 Dr. Toh has been Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Polytechnic since 1959. With increasing emphasis on industrialisation, a faculty of engineering, particularly marine engineering, naval architecture, and several other faculties in the applied sciences will be established, either as part of the University of Singapore, or Nanyang, or an Institute of Technology into which the Polytechnic will move. These institutions should complement and not duplicate each other in their fields of specialisation. In the next few years, major decisions will have to be made on the siting of the new Institute of Technology, since the location of the Singapore Polytechnic is too limited and unsuitable for expansion. -

Left Raja (Extreme Left) at the Third Annual Conference of the PAP at the Singapore Badminton Hall, 1956

Left Raja (extreme left) at the third annual conference of the PAP at the Singapore Badminton Hall, 1956. (SPH) Below First election campaign: Raja rails against the English press at a rally in Fullerton Square, 1 April 1959. (NAS) The first PAP Cabinet: (left to right) Yong Nyuk Lin, Ong Eng Guan, S. Rajaratnam, Ahmad Ibrahim, Ong Pang Boon, Goh Keng Swee, Toh Chin Chye, K. M. Byrne, Lee Kuan Yew outside the City Hall after the swearing-in ceremony, 5 June 1959. (SPH) Raja talks to the various cultural groups about promoting a Malayan consciousness, 26 July 1959. (NAS) Left Bringing Christmas cheer to blind children at Radio Singapore. With Raja is war heroine Elizabeth Choy, principal of the Singapore School for the Blind, 24 December 1959. (SPH) Below Discussing the problems facing Singapore with civil servants at the Political Study Centre, 22 October 1959. (NAS) Above Promoting photography: Raja at a pan-Malayan photographic exhibition, 31 July 1959. (NAS) Left Books: At the National Library’s opening, officiated by the Yang di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak, 12 November 1960. (SPH) Below Multiculturalism: At the Aneka Ragam Raayat concert at the City Hall steps, 5 December 1959. (SPH) Grassroots work: Opening the Kampong Glam Community Centre, 4 June 1960. (NAS) Nurturing the young at his Kampong Glam Children Club, 24 February 1963. (NAS) Being welcomed by the lion dance troupe to his community centre, 9 June 1963. (NAS) Bidding farewell to William Goode, the last British Governor in Singapore, 2 December 1959. Raja describes Goode as a politically perceptive man and a “fine example of an upright, intelligent British administrator”.