Cosmopolitan Trends in the Arts Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Goddess Euthenia • Euthenia Is Considered of Alexandrian Origin, Carrying Traits That Represent the Combination of the Egyptian Religion and the Roman Religion

ﺟﺎﻣﻌﺔ اﻟﻣﻧﯾﺎ ﻛﻠﯾﺔ اﻟﺳﯾﺎﺣﺔ واﻟﻔﻧﺎدق ﻗﺳم اﻻرﺷﺎد اﻟﺳﯾﺎﺣﻲ اﻟﻔرﻗﺔ اﻟﺛﺎﻟﺛﺔ ﻣﻘرر ارﺷﺎد ﺳﯾﺎﺣﻲ ﺗطﺑﯾﻘﻲ ٤ ﻛود اﻟﻣﻘرر: رس ٣٢٧ Selected pieces from the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria Lecture 2: - Statue of Nilus - Statue of Euthenia د. ﻓرج ﻋﺑﯾد زﻛﻲ ﻣدرس اﻻرﺷﺎد اﻟﺳﯾﺎﺣﻲ ﺑﻛﻠﯾﺔ اﻟﺳﯾﺎﺣﺔ واﻟﻔﻧﺎدق - ﺟﺎﻣﻌﺔ اﻟﻣﻧﯾﺎ وﺳﯾﻠﺔ اﻟﺗواﺻل: [email protected] Selected Pieces from the Graeco- Roman Museum in Alexandria Statue of Nilus Identification card: Material: marble Date: Roman Period, 2nd cent. AD Place of Discovery: Alexandria, Sidi Bishr. The Nile god in ancient Egypt: There was no Nile god in the ancient Egyptian civilization, but there was a deification of the annual flooding; the god Hapy. The ancient Egyptian did not worship the Nile in its abstract form, but sanctified it for being the main source of prosperity and land fertility in the country. God Nilus In Greaeco-Roman Period: The Greeks and Romans on the other hand did worship rivers which they personified as aged deities representing them with full heads of long locks and flowing beards and mustaches, often depicted, as here, reclining. Several details allude to the role of the River Nile personified as Nilus, the source of bounty and prosperity. In the Graeco- Roman Period, Nilus became the Nile god The Nile Inundation in ancient Egypt and Graeco- Roman Period: The increase in the level of the Nile was measured by an arm (1 arm = 0.52 m). This was done by means of the Nilometers that spread throughout Egypt. The Nilometers were found in some important temples. The most famous Nilometers in Egypt were the one found at Elephantine Island, that at Edfu Temple, and the one at Serapium Temple in Alexandria. -

Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine Egypt. Jack M

Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine Egypt. Jack M. Ogden ABSTRACT This study deals with the gold jewellery made and worn in Egypt during the millennium between Alexander the Great's invasion of Egypt and the Arab conquest. Funerary jewellery is largely ignored as are ornaments in the traditional, older Egyptian styles. The work draws upon a wide variety of evidence, in particular the style, composition and construction of surviving jewellery, the many repre- sentations of jewellery in wear, such as funerary portraits, and the numerous literary references from the papyri and from Classical and early Christian writers. Egypt, during the period considered, has provided a greater wealth of such information than anywhere else in the ancient or medieval world and this allows a broadly based study of jewellery in a single ancient society. The individual chapters deal with a brief historical background; the information available from papyri and other literary sources; the sources, distribution, composition and value of gold; the origins and use of mineral and organic gem materials; the economic and social organisation of the goldsmiths' trade; and the individual jewellery types, their chronology, manufacture and significance. This last section is covered in four chapters which deal respectively with rings, earrings, necklets and pendants, and bracelets and armiets. These nine chapters are followed by a detailed bibliography and a list of the 511 illustrations. Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine Egypt. In two volumes Volume 1 - Text. Jack M. Ogden Ph.D. Thesis Universtity of Durham, Department of Oriental Studies. © 1990 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. -

What Do the Artistic Representations of Antinous Reveal About His Reception in the Roman Period?’ by Emily Sherriff (STAAR 9 -2019)

St Anne’s Academic Review 2019 Emily Sherriff 1 2 What do the artistic representations of Antinous reveal about his 3 reception in the Roman period? 4 5 Classical Archaeology, Faculty of Classics 6 7 *** 8 9 Abstract 10 There are more portrait depictions of Antinous, a country boy from Asia Minor, than 11 of most Roman emperors. Does the relationship between Emperor Hadrian and 12 Antinous explain the high number of representations, or can it be explained by 13 Antinous’ deification and flexibility as a hero and god? In this article I have examined 14 a variety of artistic representations of Antinous from different locations around the 15 Roman Empire and discussed why these representations were made, and what they 16 meant for those viewing them. In doing so I show that Antinous was more than just a 17 favourite of Hadrian: in death, to the people who participated in his cult, he became a 18 genuine focus of worship, who had the tangible powers and abilities of a deity. 19 20 21 Introduction 22 Portrait depictions of Antinous were not reserved to one type or location; 23 instead, these depictions have been found in a variety of settings across the Roman 24 Empire and range from colossal statues and busts, to smaller portable items such as 25 coins and cameos (Opper 2008, 186). The variety of representations of Antinous 26 perhaps explains why there is such a vast quantity of depictions of him from the Roman 27 world. Antinous is most commonly depicted with attributes or poses usually associated 28 with deities, alluding to his deification and subsequent worship in the years following 29 his death in AD 130. -

An Orpheus Among the Animals at Dumbarton Oaks , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 33:4 (1992:Winter) P.405

MADIGAN, BRIAN, An Orpheus Among the Animals at Dumbarton Oaks , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 33:4 (1992:Winter) p.405 An Orpheus Among the Animals at Dumbarton Oaks Brian Madigan ROM TRANSITIONS between given historical periods come F some of the more problematic cases of meaning in the visual arts, where the precise significance of a subject can shift with changes in iconographic detail, the audience, or the specific context within which the subject is understood. A textile from Egypt in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks (PLATE 1) offers such a case, though it has received scant attention.1 The traditional periodic designations of 'Early Christian', 'Byzantine', or 'Coptic', which might be applied to this textile, lose some thing of their convenience here because they indicate a more precise and certain religious intention on the part of the creator and the consumer of the object than the complex conditions of surviving pagan and developing Christian traditions and our im perfect modern understanding of them would seem to warrant. The subject here is not an uncommon one in works of visual art from Late Antiquity: Orpheus charming a gathering of animals with his song. A possible Christian interpretation of Orpheus generally, and by extension this old pagan subject in particular has been much discussed. 2 But the Christian interpretations 1 Inv. 74.124.19. H. Peirce and R. Tyler, L'art byzantin (Paris 1934) 122; J. Huskinson, "Some Pagan Mythological Figures and their Significance in Early Christian Art," BRS 42 (1974) 92 n.12. J. B. Friedman, "Syncretism and Allegory in the Jerusalem Mosaic," Traditio 23 (1967) 8 n.25, refers to this textile as one of three examples of Early Christian depictions of Orpheus including a Pan or centaur; in fact there are others, as will be discussed below. -

Femina Princeps: the Life and Legacy of Livia Drusilla

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter now, including display on the World Wide Web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis. Clare A Reid April 9, 2019 Femina Princeps: The Life and Reputation of Livia Drusilla by Clare A Reid Dr. Niall Slater Adviser Department of Classics Dr. Niall Slater Adviser Dr. Katrina Dickson Committee Member Dr. James Morey Committee Member 2019 Femina Princeps: The Life and Reputation of Livia Drusilla By Clare A Reid Dr. Niall Slater Adviser An abstract of a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emory College of Arts and Sciences of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Department of Classics 2019 Abstract Femina Princeps: The Life and Reputation of Livia Drusilla By Clare Reid Livia Drusilla is not a figure many are intimately acquainted with outside the field of Classics, but, certainly, everyone has heard of her family. Wife of Augustus, the founder of the Roman Empire, mother of the emperor Tiberius, grandmother of the emperor Claudius, great-grandmother of the emperor Caligula, and great-great-grandmother of the emperor Nero, Livia gave rise to a brood (all notably not from Augustus but descended from her children from her first marriage) who shaped the early years of the Roman Empire. -

Looking at the Past of Greece Through the Eyes of Greeks Maria G

Looking at the Past of Greece through the Eyes of Greeks Maria G. Zachariou 1 Table of Contents Introduction 00 Section I: Archaeology in Greece in the 19th Century 00 Section II: Archaeology in Greece in the 20th Century 00 Section III: Archaeology in Greece in the Early 21st Century 00 Conclusion: How the Economic Crisis in Greece is Affecting Archaeology Appendix: Events, Resources, Dates, and People 00 2 Introduction The history of archaeology in Greece as it has been conducted by the Greeks themselves is too major an undertaking to be presented thoroughly within the limits of the current paper.1 Nonetheless, an effort has been made to outline the course of archaeology in Greece from the 19th century to the present day with particular attention to the native Greek contribution. The presentation of the historical facts and personalities that played a leading and vital role in the formation of the archaeological affairs in Greece is realized in three sections: archaeology in Greece during the 19th, the 20th, and the 21st centuries. Crucial historical events, remarkable people, such as politicians and scholars, institutions and societies, are introduced in chronological order, with the hope that the reader will acquire a coherent idea of the evolution of archaeology in Greece from the time of its genesis in the 19th century to the present. References to these few people and events do not suggest by any means that there were not others. The personal decisions and scientific work of native Greek archaeologists past and present has contributed significantly to the same goal: the development of archaeology in Greece. -

The Roman Imperial Cult in Alexandria During the Julio-Claudian Period

LAI t-16 The Roman Imperial Cult in Alexandria during the Julio-Claudian Period. Nicholas Eid M.A. thesis submitted to the Department of Classics, Universify of Adelaide. August 1995. ABSTRA 2 DECLARATION. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. 4 INDEX OF ABBREVIATIONS. 5 CHAPTER 1. 6 I.I INTRODUCTION 6 I.2 FACTORS AFFECTING THE NATURE OF THE IMPERIAL CULT. ll I,3 EVIDENCE FOR THE IMPERIAL CULT IN ALEXANDRIA. t4 I.4 MODERN SCHOLARSHIP ON THE IMPEzuAL CULT. t7 CHAPTER 2. t9 Religious precursors of the Imperial Cult in Alexand 19 2.I THE PHARAONIC RELIGIONS t9 2.2THE CULT OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT. 22 2.3THE PTOLEMAIC CULTS 24 2.4 CONCLUSIONS. 32 CHAPTER 3. 33 Political influences upon the structure of the Imperial Cult. 33 3.I PTOLEMAIC POLITICAL AND SOCIAL STRUCTURE. 5J 3.2THE CIVIC STRUCTURE OF ALEXANDRIA UNDER THE PTOLEMIES 34 3.3 THE INFLUENCE OF M. ANTONIUS AND CLEOPATRA. 35 3.4 THE POLITICAL STATE OF EGYPT AND ALEXANDRIA UNDER AUGUSTUS. 37 3.5 THE ROMAN ADMINISTRATION OF ALEXANDRIA. 42 3.6 ALEXANDRIAN CIVIC STRUCTURE UNDERTHE ROMANS 43 3.7 CONCLUSIONS. 47 CHA7TER 4. ¿ 49 Art and architecture. 49 4.I INTRODUCTION 49 4.2 HELLENISTIC PORTRAITURE. 50 4.3 EGYPTIAN ART. 52 4.4 ROMAN IMPEzuAL ART IN ALEXANDRIA. 53 4.5 ROMAN CULT ARCHITECTURE IN ALEXANDRIA. 51 4.6 THE ALEXANDzuAN COINAGE IN THE ruLIO-CLAUDIAN PERIOD. 65 CHAPTER 5, 71 The written evidence of the Imperial Cult. 7t 5,I INTRODUCTION 7l 5.2 THE INSCzuPTION OF TIBEzuUS CLAUDIUS BALBILLUS. 7l 5.3 THE RES GESTAE DIVI AUGUSTI. -

The Harpokratia in Graeco-Roman Egypt’

Abdelwahed, Y. (2019); ‘The Harpokratia in Graeco-Roman Egypt’ Rosetta 23: 1-27 http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue23/Abdelwahed.pdf The Harpokratia in Graeco-Roman Egypt Dr. Youssri Abdelwahed Minia University Abstract This paper attempts to reconstruct the festival of the Harpokratia and its significance in the Graeco-Roman period based on Greek papyri uncovered from Egypt and other material and written evidence. Despite the popularity of the cult of the god Harpokrates in the Graeco-Roman period, this article suggests that the festival had a local rather than a pan-Egyptian character since it was only confirmed in the villages of Soknopaiou Nesos and Euhemeria in the Arsinoite area. The Harpokratia was celebrated in Tybi and was marked with a banquet of wine and a bread and lentil-meal. Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of the festival was the purificatory public procession, which was a suitable moment for different worshippers to address the god for the fulfilment of their supplications. Keywords: Harpokrates, Harpokratia, the Arsinoite nome, Graeco-Roman Egypt. 1 Introduction The paper starts with a brief discussion of the literature on the god Harpokrates to highlight the views found in current literature on the subject and the contribution of this article. It then introduces the figure of Harpokrates and evidence in art, and then briefly explains the theological development and different associations of Harpokrates in the Graeco-Roman period. The significance of the festival from Greek papyri will be the final element presented in the article.1 There has been much discussion on child deities in ancient Egypt, whose birth was associated with the ruler’s royal legitimacy and hereditary succession.2 Like Heka-pa- khered and Ihy, respectively the child incarnations of the god Horus at Esna and Dendera, Hor-pa-khered, also known as Harpokrates, was a child-form incarnation of the god Horus.3 Scholars have approached Harpokrates from different perspectives. -

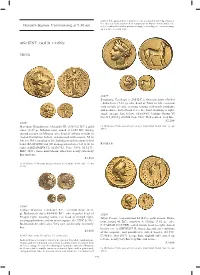

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am ANCIENT GOLD COINS

did him little good and he is usually seen as a comically suffering character. His cult was well established in Lampsacus in Mysia, which struck rare Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am silver tetradrachms with a portrait strongly resembling the evocative image on this rare electrum hekte. ANCIENT GOLD COINS GREEK 3507* Zeugitana, Carthage, (c.300 B.C.), electrum stater (Shekel - didrachm), (7.33 g), obv. head of Tanit to left, crowned with wreath of corn, wearing earring with triple pendants and necklace, dotted border, rev. free horse standing to right, single exergue line below, (cf.S.6465, Jenkins Group VI No.315 [Pl.13], cf.SNG Cop. 988). Well centred, very fi ne. $2,200 3505* Macedon, Kingdom of, Alexander III, (336-323 B.C.), gold Ex D.J.Foster Collection and previously from Spink Noble Sale 40 (lot stater, (8.57 g), Babylon mint, issued 311-305 B.C. during 2594). second satrapy of Seleucus, obv. head of Athena to right in crested Corinthian helmet, ornamented with serpent, M to left, rev. Nike standing to left, holding wreath in outstretched hand, ΒΑ ΣΙΛΕΩΣ and ΛΥ monogram in lower left fi eld, to ROMAN right ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟ[Υ], (cf.S.6702, Price 3691, M.1271, BMC 3691). Some mint bloom, otherwise nearly extremely fi ne and rare. $3,500 Ex D.J.Foster Collection and previously from Spink Noble Sale 41 (lot 2139). 3506* Lesbos, Mytilene, c.454-427 B.C., electrum hekte (2.55 g), Bodenstedt dates 454-443 B.C., obv. bearded head of 3508* Priapus right, wearing tainia, rev. -

Imperial Waters

Imperial waters Roman river god art in context Res.MA Thesis Begeleider: Dr. F.G. Naerebout Stefan Penders Tweede lezer: K. Beerden S0607320 2 Juli 2012, Leiden 1 Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1 – Depicting river gods ............................................................................................... 6 1.1 – Source: river gods in Hellenistic and early imperial art ......................................................... 6 1.2 – Surge: the Flavians ............................................................................................................ 9 1.3 – Flood: the second century .................................................................................................12 1.3.1 Trajan ..........................................................................................................................12 1.3.2 Hadrian .......................................................................................................................13 1.3.3 The Antonine emperors.................................................................................................15 1.4 – Drought: from the end of the second century to the end of antiquity ...................................16 1.5 – Murky waters ...................................................................................................................18 1.6 – Some preliminary conclusions ...........................................................................................19 -

HEPHAISTOS Was the Great Olympian God of Fire, Metalworking, Building and the Fin E Arts

HEPHAISTOS was the great Olympian god of fire, metalworking, building and the fin e arts. He had a short list of lovers in myth, although most of these appear only in the ancient genealogies with no accompanying story The two most famous of the Hephaistos "love" stories were the winning of Aphrodi te and her subsequent adulterous affair, and his attempted rape of the goddess A thene, which seeded the earth and produced a boy named Erikhthonios. DIVINE LOVES AGLAIA The Goddess of Glory and one of the three Kharites. She married Hephaisto s after his divorce from Aphrodite and bore him several divine daughters: Euklei a, Eutheme, Euthenia, and Philophrosyne. APHRODITE The Goddess of Love and Beauty was the first wife of Hephaistos. He di vorced her following an adulterous love-affair with his brother Ares, to whom sh e had borne several children. ATHENA The Goddess of War and Wisdom fought off an attempted rape by the god Hep haistos, shortly after his divorce from Aphrodite. She wiped his fluids form her leg and threw them upon the earth (Gaia) which conceived and bore a son Erikhth onios. Athena felt a certain responsibility for this child and raised it as her own in the temple of the Akropolis. GAIA The Goddess of the Earth was accidentally impregnated by the seed of Hephai stos, when Athena cast the god's semen upon the ground after his attempted rape. PERSEPHONE The gods Hephaistos, Ares, Hermes, and Apollon all wooed Persephone b efore her marriage to Haides. Demeter rejected all their gifts and hid her daugh ter away from the company of the gods.