UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO 'Saved Forever?': an Eco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect ___

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cape Hatteras National Seashore Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect ___ Review and Adjustment of Wildlife Protection Buffers April 2015 1 Department of the Interior National Park Service Environmental Assessment: Review and Adjustment of Wildlife Protection Buffers Cape Hatteras National Seashore North Carolina April 2015 Summary The National Park Service (NPS) proposes to modify wildlife protection buffers established under the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Final Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement of 2010 (ORV FEIS). This proposed action results from a review of the buffers, as mandated by Section 3057 of the Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2015, Public Law 113-291 (2014 Act). The 2014 Act directs the NPS “to ensure that the buffers are of the shortest duration and cover the smallest area necessary to protect a species, as determined in accordance with peer-reviewed scientific data.” This environmental assessment (EA) deals solely with review and modification, as appropriate, of wildlife protection buffers and the designation of pedestrian and vehicle corridors around buffers. All other aspects of the ORV FEIS remain unchanged. This EA analyzes potential impacts to the human environment resulting from two alternative courses of action. These alternatives are: alternative A (no action, i.e., continue current management under the ORV FEIS), and alternative B (modify buffers and provide additional access corridors) (the NPS preferred alternative). As more fully described in the EA, the proposed modifications to buffers and corridors in alternative B are as follows: For American oystercatcher: There would be an ORV corridor at the waterline during nesting, but only when (a) no alternate route is available, and (b) the nest is at least 25 meters from the vehicle corridor. -

A-1 Layout 1

Deer Hunt S UBSCRIBE ONLINE AT Kids: Free Ticket ‘Til March 2 THEHERALDADVOCATE.COM To State Fair . Column 12A . Story 10A The Herald-Advocate Hardee County’s Hometown Coverage 114th Year, No. 10 3 Sections, 32 Pages 70¢ Plus 5¢ Sales Tax Thursday, February 6, 2014 Boyfriend Charged In Baby’s Murder By CYNTHIA KRAHL Wauchula, has been charged Attorney’s Office, jury members permanent disability or perma- Rivera, 22, the baby’s mother, A Hardee County Grand Jury with first-degree murder and ag- agreed there was sufficient nent disfigurement.” are currently being held in the has handed up a murder indict- gravated child abuse in the Nov. cause to charge Jaimes with cap- It further accused Jaimes of Hardee County Jail on other, but ment against the boyfriend of a 5 death of 15-month-old Joel ital-felony murder and first-de- causing such “trauma to the similar, charges. Both had been woman whose baby was pro- Jordan Chavez. gree-felony abuse. head and body” of the baby be- arrested on Nov. 6 on a felony nounced dead by an Emergency Grand jurors delivered the in- Their indictment alleges that tween Nov. 4 and Nov. 5 to count of child neglect after Room doctor. dictment on Friday. between Oct. 1 and Nov. 5, cause his death “from a premed- officers investigating Joel’s Hector Tavera Jaimes, 24, of After hearing testimony and Jaimes abused Joel to the point itated design.” death allegedly disco- 310 W. Townsend St., evidence presented by the State of causing “great bodily harm, Jaimes and Kaycha Lynn See MURDER 2A Brant BRAVE BEAUTIES Jaimes Avoids Man, 81, Prison Accused Of By CYNTHIA KRAHL Of The Herald-Advocate A former city commissioner and funeral director has avoided Attempted prison and been sentenced to a lengthy probation following charges he defrauded a number of clients. -

Ebird Top 100 Birding Hot Sots

eBird Top 100 Birding Locations in Orange County 01 Huntington Central Park 02 San Joaquin Wildlife Sanctuary 03 Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve 04 Seal Beach NWR (restricted access) 05 Huntington Central Park – East 06 Bolsa Chica – walkbridge/inner bay 07 Huntington Central Park – West 08 William R. Mason Regional Park 09 Upper Newport Bay 10 Laguna Niguel Regional Park 11 Harriett M. Wieder Regional Park 12 Upper Newport Bay Nature Preserve 13 Mile Square Regional Park 14 Irvine Regional Park 15 Peters Canyon Regional Park 16 Newport Back Bay 17 Talbert Nature Preserve 18 Upper Newport Bay – Back Bay Dr. 19 Yorba Regional Park 20 Crystal Cove State Park 21 Doheny State Beach 22 Bolsa Chica - Interpretive Center/Bolsa Bay 23 Upper Newport Bay – Back Bay Dr. parking lot 24 Bolsa Chica – Brightwater area 25 Carbon Canyon Regional Park 26 Santiago Oaks Regional Park 27 Upper Santa Ana River – Lincoln Ave. to Glassel St. 28 Huntington Central Park – Shipley Nature Center 29 Upper Santa Ana River – Lakeview Ave. to Imperial Hwy. 30 Craig Regional Park 31 Irvine Lake 32 Bolsa Chica – full tidal area 33 Upper Newport Bay Nature Preserve – Muth Interpretive Center area 1 eBird Top 100 Birding Locations in Orange County 34 Upper Santa Ana River – Tustin Ave. to Lakeview Ave. 35 Fairview Park 36 Dana Point Harbor 37 San Joaquin Wildlife Area – Fledgling Loop Trail 38 Crystal Cove State Park – beach area 39 Ralph B. Clark Regional Park 40 Anaheim Coves Park (aka Burris Basin) 41 Villa Park Flood Control Basin 42 Aliso and Wood Canyons Wilderness Park 43 Upper Newport Bay – boardwalk 44 San Joaquin Wildlife Sanctuary – Tree Hill Trail 45 Starr Ranch 46 San Juan Creek mouth 47 Upper Newport Bay – Big Canyon 48 Santa Ana River mouth 49 Bolsa Chica State Beach 50 Crystal Cover State Park – El Moro 51 Riley Wilderness Park 52 Riverdale Park (ORA County) 53 Environmental Nature Center 54 Upper Santa Ana River – Taft Ave. -

SIMA Environmental Fund 2016 Year End Reports

SIMA Environmental Fund 2016 Year End Reports SIMA Environmental Fund 27831 La Paz Road Laguna Niguel, CA 92677 Phone: 949.366.1164 Fax: 949.454.1406 www.sima.com 2016 YEAR END REPORTS 5 Gyres Institute Assateague Coastal Trust Clean Ocean Action Heal the Bay North Shore Community Land Trust Ocean Institute Orange County Coastkeeper Paso Pacifico Reef Check Santa Barbara Channelkeeper Save the Waves Seymour Marine Discovery Center Surfers Against Sewage Surfing Education Association Surfrider Foundation Wildcoast Wishtoyo Foundation 2016 YEAR END REPORT 5 Gyres Institute 2016 SIMA ENVIRONMENTAL FUND YEAR END REPORT Organization: 5 Gyres Institute Contact Person: Haley Haggerstone Title: Development and Partnerships Director Purpose of Grant: SIMA Environmental Fund Grant in 2016 supported the expansion of the Ambassador program. Briefly describe the specific purpose and goal for your 2016 SIMA Environmental Fund grant. The Ambassador program is designed to educate and empower 5 Gyres’ global network of supporters to take action against plastic pollution in their communities. Ambassadors are volunteers who are provided with a solid background on plastic pollution science, policy, and solutions. This knowledge is coupled with training and tools to help Ambassadors reduce their plastic footprint and inspire their communities to do the same. The Ambassador program allows 5 Gyres small, but mighty team to have a greater impact on our mission to empower action against the global health crisis of plastic pollution. To what degree were these goals and objectives achieved? If not fully met, what factors affected the success of the project? 5 Gyres Ambassador program launched in 2015 and has grown exponentially ever since, which shows awareness about the plastic pollution issue is increasing and people want to be a part of the solution. -

Volunteer Field Guide

O R G A N I K A VOLUNTEER L I F E S T Y L E C E N T E R FIELD GUIDE S A N D I E G O C O U N T Y W I L D C O A S T . O R G / M P A W A T C H VOLUNTEER FIELD THE ULTIMATE GUIDE N O TABLE OF CONTENTS I T C 1. Introduction to Marine Protected Area (MPA) Watch U D 2. MPA Watch Goals O 3. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) R T 4. Map of San Diego County MPAs N I 5. WILDCOAST's Role in Designating MPAs FIELD RESOURCES 6. How to Conduct a Survey 7. MPA Watch Datasheet 8-9. Activity Reference Guide Survey Sites 10-15. Encinitas 16-20. La Jolla 21-25. South La Jolla 26-30. Imperial Beach L S E A 31-32. Information Management System (IMS) for Volunteers C N R O 33-34. How to Enter Data in the IMS I U T I O 35-37. Frequently Asked Questions S D E 38. Local Emergency Response D R A MARINE PROTECTED AREA (MPA) WATCH is a network of programs that support healthy oceans through community science by collecting human use data in and around our protected areas. In San Diego Co., MPA Watch is managed by WILDCOAST. WILDCOAST is an international team that conserves coastal and marine ecosystems and wildlife by: Establishing and managing protected areas. Advancing conservation policy. Directly engaging communities in scientific monitoring and conservation. 1 MPA Watch Goals To help determine how effective MPAs are at meeting their goal of enhancing recreational activities by tracking changes and trends of human use over time. -

Planning for a Coastal City: San Clemente’S Local Coastal Program

PLANNING FOR A COASTAL CITY: SAN CLEMENTE’S LOCAL COASTAL PROGRAM A Professional Project presented to California Coastal Commission, City of San Clemente, and the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of City and Regional Planning by Atousa Zolfaghari May 2013 © 2013 Atousa Zolfaghari ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ! ""! COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Planning for a Coastal City: San Clemente’s Local Coastal Program AUTHOR: Atousa Zolfaghari DATE SUBMITTED: May 2013 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Dr. Kelly Main, Assistant Professor, City and Regional Planning COMMITTEE MEMBER: Chris Clark, JD, Lecturer, City and Regional Planning COMMITTEE MEMBER: Jeff Hook, Principal Planner at City of San Clemente COMMITTEE MEMBER: Jim Pechous, City Planner at City of San Clemente ! """! ABSTRACT PLANNING FOR A COASTAL CITY: SAN CLEMENTE’S LOCAL COASTAL PROGRAM Atousa Zolfaghari This professional project assesses current conditions and regulations within San Clemente’s Coastal Zone, and provides recommendations to the City and California Coastal Commission through a draft Land Use Plan. The amended Land Use Plan will be included in the certified Local Coastal Program, which will govern decisions that determine the short and long-term conservation and use of coastal resources within San Clemente’s Coastal Zone. Local Coastal Programs (LCPs) are planning guides used by local governments for development within the Coastal Zone. They contain goals and policies for development and protection of coastal resources throughout coastal cities and counties in California. LCPs identify appropriate locations for various land uses based on their goal of environmental and sustainable development and growth. -

European Journal of American Studies, 14-4 | 2019 Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “Califor

European journal of American studies 14-4 | 2019 Special Issue: Spectacle and Spectatorship in American Culture Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “California Look” (1900s-1960s) Elsa Devienne Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15480 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.15480 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Elsa Devienne, “Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “California Look” (1900s-1960s)”, European journal of American studies [Online], 14-4 | 2019, Online since 23 December 2019, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15480 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.15480 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “Califor... 1 Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “California Look” (1900s-1960s) Elsa Devienne 1 In 1951, Life magazine ran a photo essay celebrating the vitality of West Coast youth. Among the many pictures of young Californians portrayed sailing, skiing, horse-riding, and surfing, one photograph stood out. Set in Santa Monica’s famous “Muscle Beach” playground, it pictured five bodybuilders wearing tight briefs and showing off their bulging biceps. Despite their obvious efforts to look good, the five men were mocked in the accompanying text for “carrying the body cult from the sublime to the absurd.” Clearly, the Life magazine journalists were unimpressed by such a display. As was Charles Flynn, a reader from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, who felt compelled to send a photograph, printed in the next issue’s Letters to the Editor, to “show.. -

Historic Resources Assessment Report

DRAFT HISTORIC RESOURCE TECHNICAL REPORT For the CHOLLAS CREEK MULTI-USE PATH TO BAYSHORE BIKEWAY PROJECT, SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA (Project Number 364784) Prepared for: Patrick O. Maxon, M.A., RPA BonTerra Psomas 3 Hutton Centre Drive, Suite 200 Santa Ana, CA 92707 T: (714) 751-7373 F: (714) 545-8883 Prepared by: Pamela Daly, M.S. Architectural Historian Daly & Associates 4486 University Avenue Riverside, CA 92501 (951) 369-1366 November 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 2 A. Proposed Undertaking ......................................................................................................... 2 B. Purpose and Scope of the Survey ........................................................................................ 2 C. Results of the Investigation ................................................................................................. 2 II. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 4 A. Report Organization ............................................................................................................. 4 B. Project Area ......................................................................................................................... 4 C. Project Personnel ................................................................................................................. 5 III. PROJECT SETTING -

EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME

FREE EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME Welcome to the 2016 Drug Aware Margaret River Pro, I would like to acknowledge all the sponsors who support one of Western Australia’s premier international sporting this free public event and the many volunteers who give events. up their time to make it happen. As the third stop on the Association of Professional If you are visiting our extraordinary South-West, I hope Surfers 2016 Samsung Galaxy Championship Tour, the you take the time to enjoy the region’s premium food and Drug Aware Margaret River Pro attracts a competitive field wine, underground caves, towering forests and, of course, of surfers from around the world, including Kelly Slater, its magnificent beaches. Taj Burrow and Stephanie Gilmore. SUNSMART BUSSELTON FESTIVAL The Hon Colin Barnett MLA OF TRIATHLON In fact the world’s top 36 male surfers and top 18 women Premier of Western Australia Busselton / 30 Apr-2 May will take on the world famous swell at Margaret River’s Surfer’s Point during the competition. Margaret River has become a favourite stop on the world tour for the surfers who enjoy the region’s unique forest, wine, food and surf experiences. Since 1985, the State Government, through Tourism Western Australia, and more recently with support from Royalties for Regions, has been a proud sponsor of the Drug Aware Margaret River Pro because it provides the CINÉFESTOZ FILM FESTIVAL perfect platform to show the world all that the Margaret Busselton / 24-28 Aug River Region has to offer. -

Homosexual’ from Conduct Code

SPECIAL baylorlariat com Ready for Halloween? Check out the All Hallow’s Eve special section for the Baylor Lariat Lariat’s coverage. WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE Friday | October 25, 2013 StuGov: Nix ‘homosexual’ from conduct code By Shelby Leonard (2) the uniting and strengthening affect the environment for homo- Reporter of the marital bond in self-giving sexuals on campus. love. These purposed are to be Schertz senior Kimani Mitchell Student Senate passed the achieved through heterosexual re- said, in the favor of the bill, that Sexual Misconduct Code Non- lationships within marriage. Mis- the amendment clarifies the lan- Discrimination Act, a proposal to suses of God’s gift will be under- guage already present in the code reword Baylor’s Sexual Miscon- stood to include but not limit to, and removes discriminatory lan- duct Code, in the Student Senate sexual abuse, sexual harassment, guage. meeting Thursday. sexual assault, incest, adultery, for- “We are simply clarifying lan- The act proposed to remove the nication, and homosexual acts.” guage here,” Mitchell said. “In our phrase “homosexual acts” from the The vote followed an open fo- world we don’t always take words code and replace it with the phrase rum debate with alternating for semantically. They are taken with a “non-marital consensual deviate and against speakers. pragmatic view, which is the con- sexual intercourse.” Major points expressed by notation associated with the view. The most recent version of the those in favor of the bill were that This word is discriminating. Dis- Sexual Misconduct Code was es- the amendment was technical, not crimination contextually and cul- tablished on Jan. -

Georgia Water Quality

GEORGIA SURFACE WATER AND GROUNDWATER QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT STRATEGY Okefenokee Swamp, Georgia PHOTO: Kathy Methier Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Watershed Protection Branch 2 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive Suite 1152, East Tower Atlanta, GA 30334 GEORGIA SURFACE WATER AND GROUND WATER QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT STRATEGY 2015 Update PREFACE The Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GAEPD) of the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) developed this document entitled “Georgia Surface Water and Groundwater Quality Monitoring and Assessment Strategy”. As a part of the State’s Water Quality Management Program, this report focuses on the GAEPD’s water quality monitoring efforts to address key elements identified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) monitoring strategy guidance entitled “Elements of a State Monitoring and Assessment Program, March 2003”. This report updates the State’s water quality monitoring strategy as required by the USEPA’s regulations addressing water management plans of the Clean Water Act, Section 106(e)(1). Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Watershed Protection Branch 2 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive Suite 1152, East Tower Atlanta, GA 30334 GEORGIA SURFACE WATER AND GROUND WATER QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT STRATEGY 2015 Update TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... -

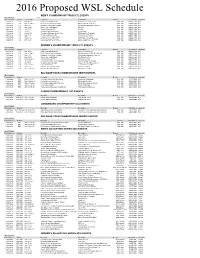

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule MEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status 2016 Tent/Confirmed Rating EventDates EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Quiksilver Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret River-West Australia Drug Aware Margaret River Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT May 10-21 Rio de Janeiro,RJ-Brazil Rio Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jun 5-17 Tavarua/Namotu-Fiji Fiji Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jly 6-17 Jeffreys Bay-South Africa J Bay Open WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Aug 19-30 Teahupo'o,Taiarapu Ouest-Tahiti Billabong Pro Teahupoo WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Sep 7-18 Trestles,California-USA Hurley Pro at Trestles WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 4-15 Landes, South West France Quiksilver Pro France WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 18-29 Peniche/Cascais-Portugal Moche Rip Curl Pro Portugal WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Dec 8-20 Banzai Pipeline,Oahu-Hawaii Billabong Pipe Masters WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A WOMEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status Tent/Confirmed Rating EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Roxy Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Women's Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret