CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Such Therefore Are the Advantages of Water Carriage; It Is Natural That the First Impr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Quarterly Report Second Quarter – January 1 to March 31, 2019

d Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Quarterly Report Second Quarter – January 1 to March 31, 2019 DISCLAIMER This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International. Submission Date: April 30, 2019 Contract Number: AID-620-C-15-00002 October 26, 2015 – October 25, 2020 COR: Olawale Samuel Submitted by: Nurudeen Lawal, Acting Chief of Party, Northern Education Initiative Plus 38 Mike Akhigbe Street, Jabi, Abuja, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Northern Education Initiative Plus - PY4 Quarter 2 Report iii CONTENT 1. PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................................................................... 5 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. 6 1.1 Program Description ...................................................................................... 8 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 12 2.1 Implementation Status ................................................................................. 15 Intermediate Result 1. Government systems strengthened to increase the number of students enrolled in appropriate, relevant, approved educational options, especially girls and out-of-school children (OOSC) in target locations ............................................................................. 15 Sub IR 1.1 Increased number of educational options (formal, NFLC) meeting -

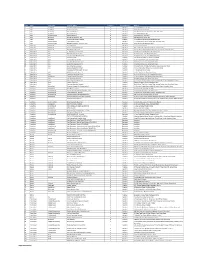

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

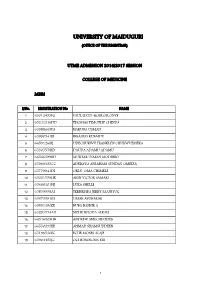

Unimaid Utme 2016 2017 First Batch

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION 2016/2017 SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICINE MBBS S/No. REGISTRATION No. NAME 1 65012453FG PAUL LIZZY-ROSE OILONYE 2 65241316DD THOMAS TIMOTHY CHINDA 3 65988663FA HARUNA USMAN 4 65880541EI IBRAHIM KUBAIDU 5 66531268IJ UDECHUKWU FRANKLYN CHUKWUEMEKA 6 65305578ID DAUDA ADAMU ADAMU 7 66546199BD MUKTAR USMAN MODIBBO 8 65989125CC ADEBAYO ABRAHAM SUNDAY OMEIZA 9 65759941DI ORLU-OMA CHIMELE 10 65021759HE AKIN VICTOR SAMARI 11 65488101HJ LUKA SHELLE 12 65859958AI TERHEMBA JERRY SAANIYOL 13 65875581IH UMAR ABUBAKAR 14 65891180EE BUBA BASHIR A 15 65295774AH NUHU RHODA ALKALI 16 66546503HB ANDREW MELCHIZEDEK 17 66550295EE AHMAD SHAMSUDDEEN 18 65198536EC ECHE MOSES ALAJE 19 65904453JC OCHE PRINCESS EHI 1 20 65299718AJ ABDULMUMIN ABUBAKAR 21 65459752FH OBI SOMTO 22 65780434FH JATTO ISA ENERO 23 66200732GG MICHAEL BLESSING 24 66299464BB MICHAEL KISLON SHITNAN 25 65903857DH USMAN ADAMA 26 66215998FC GWASKI ISAAC DIKA 27 66496897JB MOHAMMED ADAMU DUMBULWA 28 65243376GB TAHIR MUHAMMAD ARABO 29 66048182HA JERRY LEAH 30 65885079BE AHMED ABBA 31 65858960JC GAMBO LAWI 32 66246168ED SAMAILA BITRUS VISION 33 65919477CI OBI PETER CHIGOZIE 34 65548790IB GADZAMA JANADA YOHANNA 35 66193123AB MOSES MATTHEW TAIYE 36 65780170HD AERNAN SEDOO 37 65786350GA ZAKARIYYA ABDULMUMIN SANI 38 66324429JH OJIMADU CHIDINDU GODSWILL 39 65527190IF MBAYA ENOCH SAMUEL 40 65199053ED GAGA TERNGUNAN ERIC 41 65534793HB ROBERT RAKEAL 42 65305105EH YAK'OR TONGRIYANG DAWEET 43 65299765GC GONI AISHA UMAR 44 65136595BD AFOLABI ABDULWAHAB -

Lagos State Poctket Factfinder

HISTORY Before the creation of the States in 1967, the identity of Lagos was restricted to the Lagos Island of Eko (Bini word for war camp). The first settlers in Eko were the Aworis, who were mostly hunters and fishermen. They had migrated from Ile-Ife by stages to the coast at Ebute- Metta. The Aworis were later reinforced by a band of Benin warriors and joined by other Yoruba elements who settled on the mainland for a while till the danger of an attack by the warring tribes plaguing Yorubaland drove them to seek the security of the nearest island, Iddo, from where they spread to Eko. By 1851 after the abolition of the slave trade, there was a great attraction to Lagos by the repatriates. First were the Saro, mainly freed Yoruba captives and their descendants who, having been set ashore in Sierra Leone, responded to the pull of their homeland, and returned in successive waves to Lagos. Having had the privilege of Western education and christianity, they made remarkable contributions to education and the rapid modernisation of Lagos. They were granted land to settle in the Olowogbowo and Breadfruit areas of the island. The Brazilian returnees, the Aguda, also started arriving in Lagos in the mid-19th century and brought with them the skills they had acquired in Brazil. Most of them were master-builders, carpenters and masons, and gave the distinct charaterisitics of Brazilian architecture to their residential buildings at Bamgbose and Campos Square areas which form a large proportion of architectural richness of the city. -

DAVID OLUGBENGA OGUNGBILE Professor of Religious Studies

Professor David Olugbenga 0~lingbil6 B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Ife), MTS (Marvard), I'hD (lfc) Professor of Religio~rsSrlrdicc. TRULY, THE SACRED STILL DWELLS: MAKING SENSE OF EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN WORLD An Inaugural Lecture Delivered at Oduduwa Hall, Obafemi ~wolowoUniversity, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. On Tuesday, July 10, 2018. DAVID OLUGBENGA OGUNGBILE Professor of Religious Studies Inaugural Lecture Series 322 avid Olugbenga 0gungbile i1.A. (lfc). MTS (Har\,ard),I'hl) (112) ~/[,,S,TO~of'Rc~ligioi~.s .Ytz/(iic~.s Q OBAFEMI AWOLOWO UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2018 ISSN 01 89-7848 Printed by Obafemi Awolowo University Press Limited, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Truly, the Sacred Still Dwells: Making Sense of Existence in the African World )LOM.'O UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2018 Prolegornenon/Prelirninary Remarks The Inaugural Lecture is noted for providing rare opportunities to Professors so as to increase both their research and academic visibility. They are able to publicly declare and expound their past, present and future research endeavours. Mr Vice Chancellor Sir, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, I feel so honoured and humbled to be presenting today, the second Inaugural Lecture in the Department of Religious Studies of this great University, since its establishment in September, 1962. The first and only inaugural lecturer before me was Prof Matthews Ojo. All glory to the Lord! Religious Studies was one of the foundation disciplines in the Faculty of Arts and was initially run alongside Philosophy until the 1975176 ISSN 0189-7848 Academic Session when they became separate Departments. Since its inception, it has continued to offer the B.A. Religious Studies (Single Honours) and Religious Studies (Combined) with History, English or Philosophy Programme. -

Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Q3 Report April 1 – June 30, 2019

Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Q3 Report April 1 – June 30, 2019 DISCLAIMER This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International. Submission Date: July 31, 2019 Contract Number:AID-620-C-15-00002 October 26, 2015 – October 25, 2020 COR: Nura Ibrahim Submitted by: Jordene Hale, Chief of Party The Northern Education Initiative Plus 38 Mike Akhigbe Street, Jabi,Abuja, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Northern Education Initiative Plus - PY4 Quarter 3 Report 3 CONTENT 1. PROGRAM OVERVIEW .................................................................................................5 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................6 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................10 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................12 2.1 Implementation Status ..................................................................................16 Intermediate Result 1. Government systems strengthened to increase the number of students enrolled in appropriate, relevant, approved educational options, especially girls and out-of-school children (OOSC) in target locations ..............................................................................16 Sub IR 1.1 Increased number of educational options (formal, NFLC) meeting school quality and safety benchmarks: .............................................16 -

Governance and Human Security in Anambra State, 1999-2007

GOVERNANCE AND HUMAN SECURITY IN ANAMBRA STATE, 1999-2007 BY GINIKA UCHE-NWANKWO PG/MSC/08/48783 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA NSUKKA FEBRUARY, 2010 i GOVERNANCE AND HUMAN SECURITY IN ANAMBRA STATE, 1999-2007 BY GINIKA UCHE-NWANKWO PG/MSC/08/48783 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (MS.c) IN POLITICAL SCIENCE (GOVERNMENT) TO THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. SUPERVISOR: PROF. JONAH ONUOHA Ph.D. FEBRUARY, 2010 ii APPROVAL PAGE GINIKA UCHE-NWANKWO a postgraduate student in the Department of Political Science with Registration Number PG/MS.c/08/48783 has satisfactorily completed research requirements for the award of Master of Science in Political Science (International Relations). The work embodied in this thesis is original and has not been submitted in part or in full for another degree of this or any other university, to the best of our knowledge: ---------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Jonah Onuoha Ph.D Prof. E. O. Ezeani, Ph.D (Supervisor) (Head of Department) ---------------------------------- ------------------------------- External Examiner Dean iii DEDICATION To my brother Reverend Father, Prof. Ben, Ejide who inspired me iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this project report is due to the contribution of people too numerous to mention. However, I must thank my husband for his patience, understanding, prayers and financial support . I have benefited greatly from the assistance of my supervisor, Prof. Jonah Onuoha Ph.D., who expertly supervised this study. I am also grateful to the academic staff of the Department of Political Science, especially Prof. Ikejiani-Clark who encouraged and offered useful suggestions to me during the period of this programme. -

Parochial Political Culture: the Bane of Nigeria Development Rosemary Anazodo (Ph.D) Department of Public Administration Nnamdi

Review of Public Administration & Management Vo. 1 No. 2 Parochial Political Culture: The Bane of Nigeria Development Rosemary Anazodo (Ph.D) Department of Public Administration Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. E-mail:[email protected] Agbionu, Tina Uchenna Department of Business Administration Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nig E-mail:[email protected] Ezenwile Uche Department of Public Administration Anambra State University, Uli Anambra State Abstract This paper examined the effect of parochial political culture on national development in Nigeria. It is imperative at this time more than any other in the history of Nigeria, a country at crossroad to vigorously address the challenges posed by the parochial political culture , without which political stability, political innovation, national development among others would be a mirage. For many decades Nigeria has been on a steady decline in regards to all indicators of national development. On this premise the paper intends to investigate how Nigeria’s political culture impedes her national development. Based on the assertions above, some objectives were formulated to guide the study. Theories of two republics and Prebendalism formed the basis of the study. Some findings were made and recommendations provided on the way forward . Keywords; Parochial, Political Culture, Development. Introduction Nigeria is sadly at the other side of political and economic development. Annual income per head is dismally low, economic and social infrastructures are underdeveloped and manufacturing base is weak. 1 Review of Public Administration & Management Vo. 1 No. 2 Nigeria is a rich country whose economy has been mismanaged over the years. The excellent investment opportunities have been affected by unstable political atmosphere and threats to security of life and property (Abimboye, 2010:18). -

The Making of Sani Abacha There

To the memory of Bashorun M.K.O Abiola (August 24, 1937 to July 7, 1998); and the numerous other Nigerians who died in the hands of the military authorities during the struggle to enthrone democracy in Nigeria. ‘The cause endures, the HOPE still lives, the dream shall never die…’ onderful: It is amazing how Nigerians hardly learn frWom history, how the history of our politics is that of oppor - tunism, and violations of the people’s sovereignty. After the exit of British colonialism, a new set of local imperi - alists in military uniform and civilian garb assumed power and have consistently proven to be worse than those they suc - ceeded. These new vetoists are not driven by any love of coun - try, but rather by the love of self, and the preservation of the narrow interests of the power-class that they represent. They do not see leadership as an opportunity to serve, but as an av - enue to loot the public treasury; they do not see politics as a platform for development, but as something to be captured by any means possible. One after the other, these hunters of fortune in public life have ended up as victims of their own ambitions; they are either eliminated by other forces also seeking power, or they run into a dead-end. In the face of this leadership deficit, it is the people of Nigeria that have suffered; it is society itself that pays the price for the imposition of deranged values on the public space; much ten - sion is created, the country is polarized, growth is truncated. -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts may not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the copyright owner. Center for Research Libraries Identifier: f-n-000001 Downloaded on: Jun 15, 2017 5:03:23 PM r:; • lifgSit ■ » Federal RepubUc of Nigeria Official Gazette No. 36 Lagos - 12th July, 1973 Vol. 60 CONTENTS Page Page Movements • e . 1018-26 Establishment of Denton StreetPostal Agency, Ebute Metta ■ 4 • • » ■ e 1029 Yaba College of Tec^ology—Appointment (States Representatives of Coun^) Notice 1072 «« «« «a •• a, aa lyin Postal Agency—^Introduction of Savings 1026 Bank Fadlities 1030 Yaba College of Technology—Appointment Loss of Local Purchase Orders .. 1030 (States Representatives of Coun^) Notice 1973 .. .. 1626 Loss of local Purchase Order Booklet .. 1030 Applications under Trade Unions Act Cap. Loss of Payable Orders .. 1030 200 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria and Federal Government Bursary Scheme for the Lagos 1958 • • . -

Governance and Insecurity in South East Nigeria.Pmd

GOVERNANCE AND INSECURITYYY IN SOUTH EAST NIGERIA Edited by: Ukoha Ukiwo and Innocent Chukwuma CLEEN Foundation First published in 2012 by: CLEEN Foundation Lagos Office: 21, Akinsanya Street Taiwo Bus-Stop Ojodu Ikeja, 100281 Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria Tel: 234-1-7612479, 7395498 Abuja Office: 26, Bamenda Street, off Abidjan Street Wuse Zone 3, Abuja, Nigeria Tel: 234-9-7817025, 8708379 Owerri Office: Plot 10, Area M Road 3 World Bank Housing Estate Owerri, Imo State Tel: 083-823104, 08128002962, 08130278469 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cleen.org ISBN: 978-978-51062-2-0 © Whole or part of this publication may be republished, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted through electronic, photocopying, mechanical, recording or otheriwe, with proper acknowledgement of the publishers. Typesetting: Blessing Aniche-Nwokolo Cover concept: Gabriel Akinremi The mission of CLEEN Foundation is to promote public safety, security and accessible justice through empirical research, legislative advocacy, demonstration programmes and publications, in partnership with government and civil society. Table of Content List of tables v Acknowledgement vi Preface viii Chapters: 1. Framework for Improving Security and Governance in the Southeast by Ukoha Ukiwo 1 2. Governance and Security in Abia State by Ukoha Ukiwo and Magdalene O Emole 24 3. Governance and Security in Anambra State by Chijoke K. Iwuamadi 58 4. Governance and Security in Ebonyi State by Smart E. Otu 83 5. Governance and Security in Enugu State by Nkwachukwu Orji 114 6. Governance and Security -

4 Thesis.Pdf

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background to the Study The work explores the evolution of the local government institution in Urhoboland from 1916 to 1999. As a study on grassroots administration in the area, it invariably covers the impact of the system, especially in terms of political and socio-economic development. Scholarly studies have demonstrated the relevance of grassroots political institutions to societal development and indicated that they started with the earliest political systems. On the other hand, local government is the modern terminology for this concept. Therefore, the study analyses the traditional grassroots institution in Urhoboland by 1916 before exploring the gradual creation of totally new grassroots structures and paradigms and their attendant dynamics which in some cases were more complex and also different in many respects from the traditional system among the Urhobo. It has been observed that local government administration is yet to live up to expectation in Nigeria1 even though it could be a key instrument of promoting national development. This has made it imperative to examine the index details in each locality in order to pinpoint the extent to which they are reflected in analysis of the general factors in the evolution of the system at the national and regional levels. For instance, the experience of the Urhobo and other ethnic groups in the former Warri District,2 shows that what is now known as the “Niger Delta Question”3 has some link with the nature of the management of grassroots administration. 1 On the one hand, the major policies of British colonial local government system in Urhoboland gradually eroded some of its basic elements of political dynamism and compounded the nature of grassroots politics and inter-group relations.