Mercer Street 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hbo Premieres the Third Season of Game of Thrones

HBO PREMIERES THE THIRD SEASON OF GAME OF THRONES The new season will premiere simultaneously with the United States on March 31st Miami, FL, March 18, 2013 – The battle for the Iron Throne among the families who rule the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros continues in the third season of the HBO original series, Game of Thrones. Winner of two Emmys® 2011 and six Golden Globes® 2012, the series is based on the famous fantasy books “A Song of Ice and Fire” by George R.R. Martin. HBO Latin America will premiere the third season simultaneously with the United States on March 31st. Many of the events that occurred in the first two seasons will culminate violently, with several of the main characters confronting their destinies. But new challengers for the Iron Throne rise from the most unexpected places. Characters old and new must navigate the demands of family, honor, ambition, love and – above all – survival, as the Westeros civil war rages into autumn. The Lannisters hold absolute dominion over King’s Landing after repelling Stannis Baratheon’s forces, yet Robb Stark –King of the North– still controls much of the South, having yet to lose a battle. In the Far North, Mance Rayder (new character portrayed by Ciaran Hinds) has united the wildlings into the largest army Westeros has ever seen. Only the Night’s Watch stands between him and the Seven Kingdoms. Across the Narrow Sea, Daenerys Targaryen – reunited with her three growing dragons – ventures into Slaver’s Bay in search of ships to take her home and allies to conquer it. -

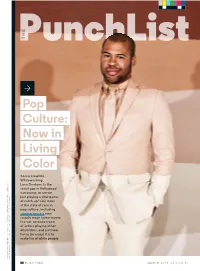

Pop Culture, Including at the Stateof Race in of Catch-Up? Gqlooks Just Playing Aslow Game Narrowing, Or Are We Racial Gapinhollywood Lena Dunham

THE > Pop Culture: Now in Living Color #oscarssowhite. Whitewashing. Lena Dunham. Is the racial gap in Hollywood narrowing, or are we just playing a slow game of catch-up? GQ looks at the state of race in pop culture, including JORDAN PEELE’S new racially tense horror movie, the not-so-woke trend of actors playing other ethnicities, and just how funny (or scary) it is to make fun of white people STYLIST: MICHAEL NASH. PROP STYLIST: FAETHGRUPPE. GROOMING: HEE SOO SOO HEE GROOMING: FAETHGRUPPE. STYLIST: PROP NASH. MICHAEL STYLIST: KLEIN. CALVIN TIE: AND SHIRT, SUIT, GOETZ. + MALIN FOR KWON PETER YANG MARCH 2017 GQ. COM 81 THEPUNCHLIST Jordan Peele Is Terrifying The Key & Peele star goes solo with a real horror story: being black in America jordan peele’s directorial debut, Get Out, is the story of a black man who visits the family of his white girlfriend and begins to suspect they’re either a little racist or plotting to annihilate him. Peele examined race for laughs on the Emmy-winning series Key & Peele. But Get Out expresses racial tension in a way we’ve never seen before: as the monster in a horror Why do you think that is? the layer of race that enriches flick. caity weaver EGG ON YOUR talked to Peele in his Black creators have not been and complicates that tension given a platform, and the [in Get Out] becomes relatable. (BLACK)FACE editing studio about African-American experience An index of racially using race as fodder for can only be dealt with by My dad is a black guy from questionable role-playing a popcorn thriller and an African-American. -

Doctor Extraño: Marvel Lo Ha Vuelto a Lograr ¡Por Fin! Por Fin Marvel

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 26, nº2 (2016) · ISSN: 2014-668X altura de Iron Man o Los Vengadores — véase los casos de Vengadores: La era de Ultrón o Capitán América: Civil War, y un Ant-Man, que aunque muy divertido, se notaba que estaba hecho a medias—, y ahora ha cogido un personaje nuevo para el Universo Cinematográfico, tan desconocido para el gran público como lo fueron los Guardianes de la Galaxia, y han conseguido hacer un auténtico peliculón… Bueno, un auténtico peliculón dentro de los cánones de Marvel. Sin entrar en demasiados detalles, ya que esta es una película para descubrir en las salas, la historia gira en torno al Dr. Stephen Strange, un neurocirujano obsesionado en su ego como gran médico, y que solo se preocupa por los casos que le pueden reportar un éxito tan tangible como su Doctor Extraño: Marvel lo ha vuelto a ático, su colección de relojes o sus lograr deportivos. Pero todo cambia cuando sufre un terrible accidente que le Por FRANCESC MARÍ COMPANY destroza sus manos y, aunque trata por todos los medios recuperar sus preciadas ¡Por fin! Por fin Marvel Studios herramientas de trabajo, descubre que ha hecho lo que tenía que hacer. nunca más volverá a operar. Salvando todas las diferencias Desesperado decide seguir la misteriosa argumentales, Doctor Extraño es como pista de Kamar-Taj, en Nepal, un lugar Guardianes de la Galaxia. Me explico: en el que alguien supuestamente puede después de unas cuantas películas, que si recuperarse mágicamente de durísimas bien no eran malas, tampoco estaban a la lesiones. Sin embargo, descubrirá un 98 FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. -

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines As a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Ralina Joseph, Chair LeiLani Nishime Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication ©Copyright 2013 Jennifer McClearen Running head: AUDIENCE READINGS OF ACTION HEROINES University of Washington Abstract Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen Chair of Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Ralina Joseph Department of Communication In this paper, I employ a feminist approach to audience research and examine the individual interviews of 11 undergraduate women who regularly watch and enjoy action heroine films. Participants in the study articulate action heroines as visual metaphors for career and academic success and take pleasure in seeing women succeed against adversity. However, they are reluctant to believe that the female bodies onscreen are physically capable of the action they perform when compared with male counterparts—a belief based on post-feminist assumptions of the limits of female physical abilities and the persistent representations of thin action heroines in film. I argue that post-feminist ideology encourages women to imagine action heroines as successful in intellectual arenas; yet, the ideology simultaneously disciplines action heroine bodies to render them unbelievable as physically powerful women. -

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Michelle, My Belle

JUDY, JUDY, JUDY ACCESSORIES: Luxury handbag brand Judith Leiber introduces a WWDSTYLE lower-priced collection. Page 11. Michelle, My Belle A rainbow of color may have populated the red carpet at this year’s Oscars, but Best Actress nominee Michelle Williams went countertrend, keeping it simply chic with a Chanel silver sheath dress. For more on the Oscars red carpet, see pages 4 and 5. PHOTO BY DONATO SARDELLA 2 WWDSTYLE MONDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2011 Elizabeth Banks Livia with Tom Ford. and Colin eye Firth. Claire Danes in Chanel with Hugh Dancy Emma Stone in at the Chanel Chanel at the Jennifer dinner. Chanel dinner. Hudson Livia and Colin Firth January Jones in Chanel at the Chanel The Endless Season dinner. Perhaps it was because James Franco — the current “What’s Harvey’s movie?” he asked. “‘The King’s standard-bearer for actor-artistes the world over — Speech’? I liked that very much.” was co-hosting the ceremony, or perhaps a rare SoCal But it wasn’t all high culture in Los Angeles this week. cold front had Hollywood in a more contemplative The usual array of fashion house- and magazine-sponsored mood than normal, but the annual pre-Oscar party bashes, congratulatory luncheons, lesser awards shows rodeo had a definite art world bent this year. and agency schmooze fests vied for attention as well. Rodarte designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy On Wednesday night — a day before the scandal that kicked things off Wednesday night with an exhibit engulfed the house and its designer, John Galliano — of their work (including several looks they created Harvey Weinstein took over as co-host of Dior’s annual for Natalie Portman in “Black Swan”) sponsored Oscar dinner, and transformed it from an intimate affair by Swarovski at the West Hollywood branch of beneath the Chateau Marmont colonnade to a Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art 150-person event that took over the hotel’s entire and an accompanying dinner at Mr. -

The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie

DOI: 10.24843/JH.2018.v22.i03.p30 ISSN: 2302-920X Jurnal Humanis, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Unud Vol 22.3 Agustus 2018: 771-780 The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie Ni Putu Ayu Mitha Hapsari1*, I Nyoman Tri Ediwan2, Ni Luh Nyoman Seri Malini3 [123]English Department - Faculty of Arts - Udayana University 1[[email protected]] 2[[email protected]] 3[[email protected]] *Corresponding Author Abstract The title of this paper is The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. This study focuses on categorization and function of the characters in the movie and conflicts in the main character (external and internal conflicts). The data of this study were taken from a movie entitled Doctor Strange. The data were collected through documentation method. In analyzing the data, the study used qualitative method. The categorization and function were analyzed based on the theory proposed by Wellek and Warren (1955:227), supported by the theory of literature proposed by Kathleen Morner (1991:31). The conflict was analyzed based on the theory of literature proposed by Kenney (1966:5). The findings show that the categorization and function of the characters in the movie are as follows: Stephen Strange (dynamic protagonist character), Kaecilius (static antagonist character). Secondary characters are The Ancient One (static protagonist character), Mordo (static protagonist character) and Christine (dynamic protagonist character). The supporting character is Wong (static protagonist character). Then there are two types of conflicts found in this movie, internal and external conflicts. Keywords: Character, Conflict, Doctor Strange. Abstrak Judul penelitian ini adalah The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. -

Negotiating the Non-Narrative, Aesthetic and Erotic in New Extreme Gore

NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Colva Weissenstein, B.A. Washington, DC April 18, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Colva Weissenstein All Rights Reserved ii NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. Colva O. Weissenstein, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Garrison LeMasters, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis is about the economic and aesthetic elements of New Extreme Gore films produced in the 2000s. The thesis seeks to evaluate film in terms of its aesthetic project rather than a traditional reading of horror as a cathartic genre. The aesthetic project of these films manifests in terms of an erotic and visually constructed affective experience. It examines the films from a thick descriptive and scene analysis methodology in order to express the aesthetic over narrative elements of the films. The thesis is organized in terms of the economic location of the New Extreme Gore films in terms of the film industry at large. It then negotiates a move to define and analyze the aesthetic and stylistic elements of the images of bodily destruction and gore present in these productions. Finally, to consider the erotic manifestations of New Extreme Gore it explores the relationship between the real and the artificial in horror and hardcore pornography. New Extreme Gore operates in terms of a kind of aesthetic, gore-driven pornography. Further, the films in question are inherently tied to their economic circumstances as a result of the significant visual effects technology and the unstable financial success of hyper- violent films. -

JJ Makaro 2Nd Unit Director / Stunt Coordinator / Stunt Performer

JJ Makaro 2nd Unit Director / Stunt Coordinator / Stunt Performer Office: 604-299-7050 Cel: 604-880-4478 Website: www.stuntscanada.com DGC/UBCP/ACTRA Member Height: 5’10 Weight: 175 Hair: Silver Eyes: Blue Waist: 32 Inseam: 32 Sleeve: 33 Shoe: 9 ½ Hat: 7 1/8 Neck: 16 Jacket: 40 MED LEO AWARDS NOMINEE – BEST STUNT COORDINATION IN A FEATURE FILM – “NIGHT AT THE MUSEUM: BATTLE OF THE SMITHSONIAN - 2009 TAURUS WORLD STUNT AWARD NOMINEE – BEST STUNT COORDINATOR/2ND UNIT DIRECTOR – “3000 MILES TO GRACELAND” – 2001 2ND UNIT DIRECTING SHOW PRODUCER/PM DIRECTOR The Guest (Miramax) Paddy Cullen/Fran Rosati David Zucker Out Cold (Spyglass) Lee R. Mayes/Fran Rosati Brendan & Emmett Malloy Freedom (Silver Pictures/WB TV) Simon Abbott Various Saving Silverman (Columbia/Tristar) Neil Moritz/Warren Carr Dennis Dugan A Winter’s Tale (Mandeville) Preston Fisher/Gran Rosati Michael Switzer Scary Movie (Miramax) Lee R. Mayes/Fran Rosati Keenan Ivory Wayans Max Q (Disney/Bruckheimer) David Roessel/Andrew Maclean Michael Shapiro Nightman (Crescent Entertainment) Allen Eastman, Ted Bauman/Bob Simmonds Various Suspect Behavior (Disney) Salli Newman/Rose Lam Rusty Cundieff Three (Warner Brothers TV) Brooke Kennedy, Charles S. Carrol/Ted Various Bauman, Fran Rosati Police Academy – The Series (Warner Brothers TV Paul Maslansky/James Margellos Various Sleepwalkers (Columbia/Tristar) David Nutter, Tim Iacofano/Wendy Williams Various Intensity (Mandalay Productions) Preston Fisher/Wendy Williams Yves Simoneau Bounty Hunters II (Cine-Vu) Jeff Barmash, George Erschbamer/John -

February 8, 2021 Dear President Biden and Vice President Harris

February 8, 2021 Dear President Biden and Vice President Harris, Thank you for your administration’s early focus on climate change, tribal sovereignty, and racial justice and equity, including your decision to stop the Keystone XL pipeline. We are also grateful for your critical efforts to save lives and address the COVID-19 pandemic that is disproportionately impacting BIPOC communities across our country. As your Administration takes action to address the climate crisis and strengthen relationships with Indigenous communities, we respectfully urge you to reverse another harmful Trump Administration decision and immediately shut down the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) during its court-ordered environmental review. In 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe became the epicenter of a global climate justice movement to stop the illegal construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The pipeline had originally been slated to cross the Missouri River north of Bismarck, ND, yet the risk of an oil spill on the city’s 90% white inhabitants was deemed too great. The new crossing site shifted the risk to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, in a location of key religious and cultural importance, including the burial grounds of their ancestors. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approved several of the required permits without conducting an Environmental Impact Statement or adequately consulting with the Tribe. After several months of peaceful demonstrations and the advocacy of tens of millions of Americans, President Obama listened to the demands of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. He declined to issue the final pipeline permit. Then the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers announced they would conduct a full environmental review, which would focus on the Tribe’s treaty rights. -

Scarlett Johnasson

Scarlett Johnasson Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated wiki entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the convenience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mission: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally. The content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accurate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. The publisher does not guarantee the validity of the information found here. If you need specific advice (for example, medical, legal, financial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled "References". Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License" All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Scarlett Johansson 1 North (film) 15 Just Cause (film) 20 Manny & Lo 22 If Lucy Fell 24 Home Alone 3 26 The Horse Whisperer 29 My Brother -

Lack of Diversity in Movies Continues by REEMA SALEH Them Under the Guise of Wanting More Money When in for Them Has Been Around for All This Time

6 News | The Cavalier | May lack of diversity in movies continues by REEMA SALEH them under the guise of wanting more money when in for them has been around for all this time. reality, every movie that has been whitewashed ever has “In ‘Pan,’Tiger Lilly is supposed to be Native Ameri- ollowing the release of photographs by bombed,” Baylis said. “These roles are the ones that are can, and she is played by Rooney Mara, who is very white. Paramount Pictures that unveiled Scarlett being given to white people and people of color are being There’s the “The Lone Ranger”, where Johnny Depp plays Johansson as the main character of this erased from their own stories.” a very racist version of a Native American. There’s Aloha, American adaptation of Ghost in the While Scarlett Johansson’s casting has been contro- where Emma Stone plays an Asian-American character Shell, fans of the original franchise and versial, claims that Paramount Studios have been experi- when she is very white. You have “The Last Airbender”, others grew angry at the casting of a menting with computer imagery to make Johanson appear where only the villains and extras are portrayed by Asian white woman to play the Japanese Mo- more Asian has been met with more anger. actors in a pretty Asian-influenced film,” Baylis said. “There F toko Kusanagi. “I’m a little bit bothered that rather than hire an are so many movies that consistently do this, but all of “By casting a white actor into a role that would have Asian actor to play the part they would create and devel- these movies have bombed.