Traditions and Innovations in Teaching Philological Disciplines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dynamics of FM Frequencies Allotment for the Local Radio Broadcasting

DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING IN UKRAINE: 2015–2018 The Project of the National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine “Community Broadcasting” NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 Overall indicators As of 14 December 2018 local radio stations local radio stations rate of increase in the launched terrestrial broadcast in 24 regions number of local radio broadcasting in 2015―2018 of Ukraine broadcasters in 2015―2018 The average volume of own broadcasting | 11 hours 15 minutes per 24 hours Type of activity of a TV and radio organization For profit radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations Non-profit (communal companies, community organizations) radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 The competitions held for available FM radio frequencies for local radio broadcasting competitions held by the National Council out of 97 FM frequencies were granted to the on consideration of which local radio stations broadcasters in 4 format competitions, were granted with FM frequencies participated strictly by local radio stations Number of granted Number of general Number of format Practical steps towards implementation of the FM frequencies competitions* competitions** “Community Broadcasting” project The -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Problems of Mining the Prospective Coal-Bearing Areas in Donbas

E3S Web of Conferences 123, 01011 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf /201912301011 Ukrainian School of Mining Engineering - 2019 Problems of mining the prospective coal- bearing areas in Donbas Serhii Nehrii1*, Tetiana Nehrii1, Leonid Bachurin2, and Hanna Piskurska3 1Donetsk National Technical University, Department of Mineral Deposits Development, 2 Shybankova Sq., 85300 Pokrovsk, Ukraine 2Donetsk National Technical University, Department of Production Management and Occupational Safety, 2 Shybankova Sq., 85300 Pokrovsk, Ukraine 3Donetsk National Technical University, Department of Language Training, 2 Shybankova Sq., 85300 Pokrovsk, Ukraine Abstract. The prospective coal-bearing areas of Donbas in Ukraine have been identified. Their development will increase the energy security of Ukraine. It has been suggested that the development of these areas will involve mining the coal seams in a weak roof and floor environment, which are characterized by low compressive strength, lower density and a tendency to plastic deformations. The stability has been assessed of the rocks outcrop on the contour of mine roadways for mines operating in these areas. It has been determined that roof rocks in most of these mines belong to a range of groups from very unstable to moderately stable, and the bottom rocks are, in most cases, prone to swelling. This complicates the intensive prospective areas mining with the use of advanced technologies, as well as secondary support for retained goaf-side gateroads with limited yielding property. The mines have been determined, for which this issue is relevant when mining the seams with further increase in the depth. The mechanism of displacement in the secondary supports and has been exemplified and studied using the numerical method. -

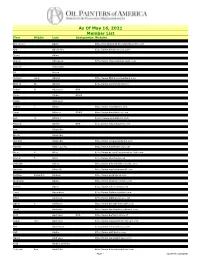

As of May 16, 2021 Member List

As Of May 16, 2021 Member List First Middle Last Designation Website Clarice Nell Aaron Genevieve Abate http://genabate333.fineartstudioonline.com Lynn Abbott http://www.lynnabbottstudios.com Kim Abernethy http://www.kimabernethy.com Liz Abeyta http://www.lizabeyta.com Bryan Abing Susan Abma http://www.susanabma.com Sharon Abshagen http://www.sharonabshagenart.com Angela Marie Accarino http://www.sunfishart.com Benone Achiriloaie Sandra Ackerman Ed Acuna Amy Adams http://www.Amyadamsfineart.com Michael Lynn Adams http://www.MichaelLynnAdams.com Peter Adams OPAM http://www.Americanlegacyfinearts.com Warren W. Adams http://www.wyomingartist.net Dustin Adamson http://www.dustinadamsonfineart.com Robert N. Adamson OPA Teresa Adaszynska http://www.adaszynskafineart.com Cyrus Afsary OPAM Priya Ahlawat http://www.priyaahlawat.com Susan Aitcheson Michael Aitken Robert T. Akers http://www.robertakers.com Robert Lawrence Akey http://www.robakey.com Daud Akhriev OPAM http://www.daudakhriev.com Lee Alban OPA http://www.leealban.com Ann H. Aldinger https://www.annaldinger.com Christy Carroll Aldredge http://www.christyaldredge.com Edward Aldrich OPA http://www.edwardaldrich.com Anne Aleshire http://www.annealeshire.com Ann Alexander Charles David Alexander http://www.charlesdavidalexander.com Gloria Alexander Joseph Alexander http://www.josephalexanderstudio.com Richard Alexander http://www.richalexanderart.com Stanton deForest Allaben http://www.stantonallabenart.com Martha Allan Laverty http://www.marthalaverty.com Laura Lawson Allee http://www.llawsonallee.faso.com/ -

From Region to Region 15-Day Tour to the Most Intriguing Places of Ancient

Ukraine: from region to region 15-day tour to the most intriguing places of ancient Ukraine All year round Explore the most interesting sights all over Ukraine and learn about the great history of the country. Be dazzled by glittering church domes, wide boulevards and glamorous nightlife in Kyiv, the capital city; learn about the Slavonic culture in Chernihiv and dwell on the Cossacks epoch at the other famous towns; admire the palace and park complexes, imagining living in the previous centuries; disclose the secrets of Ukrainian unique handicrafts and visit the magnificent monasteries. Don’t miss a chance to drink some coffee in the well-known and certainly stunning Western city Lviv and take an opportunity to see the beautiful Carpathian Mountains, go hiking on their highest peak or just go for a stroll in the truly fresh air. Get unforgettable memories from Kamyanets-Podilsky with its marvelous stone fortress and take pictures of the so called “movie-star fortress” at Khotyn. Day 1, Kyiv Meeting at the airport in Kyiv. Transfer to a hotel. Accommodation at the hotel. Welcome dinner. Meeting with a guide and a short presentation of a tour. Day 2, Kyiv Breakfast. A 3-hour bus tour around the historical districts of Kyiv: Golden Gate (the unique monument which reflects the art of fortification of Kievan Rus), a majestic St. Sophia’s Cathedral, St. Volodymyr’s and St. Michael’s Golden Domed Cathedrals, an exuberant St. Andrew’s Church. A walk along Andriyivsky Uzviz (Andrew’s Descent) – Kyiv’s “Monmartre” - where the peculiar Ukrainian souvenirs may be bought. -

This Content Downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec

This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions LETTERS FROM HEAVEN: POPULAR RELIGION IN RUSSIA AND UKRAINE This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions This page intentionally left blank This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Edited by JOHNPAUL HIMKA and ANDRIY ZAYARNYUK Letters from Heaven Popular Religion in Russia and Ukraine UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions www.utppublishing.com © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2006 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN13: 9780802091482 ISBN10: 0802091482 Printed on acidfree paper Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Letters from heaven : popular religion in Russia and Ukraine / edited by John•Paul Himka and Andriy Zayarnyuk. ISBN13: 9780802091482 ISBN10: 0802091482 1. Russia – Religion – History. 2. Ukraine – Religion – History. 3. Religion and culture – Russia (Federation) – History. 4. Religion and culture – Ukraine – History. 5. Eastern Orthodox Church – Russia (Federation) – History. 6. Eastern Orthodox Church – Ukraine – History. I. Himka, John•Paul, 1949– II. Zayarnyuk, Andriy, 1975– BX485.L48 2006 281.9 947 C20069037116 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. -

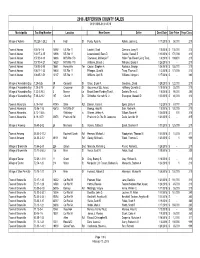

2018 Sales Report

2018 JEFFERSON COUNTY SALES 01/01/2018-01/31/2018 Municipality Tax Map NumberLocation New Owner Seller Deed Date Sale Price Prop Class Village of Adams 112.28-1-28.2 15 High St Purdy, Ryan A. Rohde, Joanne L 1/17/2018$ 58,000 210 Town of Adams 100.14-1-6 14592 US Rte 11 Laisdell, Scott Clemons, Larry R 1/8/2018$ 135,000 210 Town of Adams 100.17-2-15 13906 US Rte 11 Lewandowski, Sean D. Gaulke, Russell S 1/10/2018$ 170,000 210 Town of Adams 107.00-4-13 16686 NYS Rte 178 Townsend, McKenzie F. Haller Fam Revoc Living Trust, 1/8/2018$ 169,600 210 Town of Adams 107.00-4-21 16520 NYS Rte 178 Williams, Brandi J. Williams, Brandi J 1/26/2018$ - 210 Town of Adams 108.05-2-80 18661 Honeyville Ter Casion, Stephen A. Roukous, George 1/26/2018$ 155,000 210 Town of Adams 108.17-1-33 10604 US Rte 11 Pfleegor, Chad M. Tharp, Thomas S 1/3/2018$ 173,000 210 Town of Adams 108.05-1-51 13137 US Rte 11 Williams, April R. Williams, Morgan J 1/17/2018$ - 280 Village of Alexandria Bay 7.29-3-26 39 Cornwall St Olson, Bryan R. Goudreau, David 1/29/2018$ 122,000 210 Village of Alexandria Bay 7.29-3-78 81 Crossmon St Gouverneur S&L Assoc, Hoffberg, Camette C 1/18/2018$ 25,000 210 Village of Alexandria Bay 7.22-2-29.3 3 Mance Ln Broad Street Funding Trust I, Daniels, Emma L 1/5/2018$ 95,000 280 Village of Alexandria Bay 7.38-2-21.2 107 Church St Schreiber, Kenneth M. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2001, No.37

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Verkhovna Rada finally passes election law — page 3. •A journal from SUM’s World Zlet in Ukraine — pages 10-11. • Soyuzivka’s end-of-summer ritual — centerfold. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIX HE No.KRAINIAN 37 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2001 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine UKRAINE REACTS TO TERRORIST ATTACKS ON U.S. EU Tand UkraineU W by Roman Woronowycz President Leonid Kuchma, who had and condemned the attacks, according to Kyiv Press Bureau just concluded the Ukraine-European Interfax-Ukraine. meet in Yalta Union summit in Yalta with European “We mourn those who died in this act KYIV – Ukraine led the international Commission President Romano Prodi and response to the unprecedented terrorist of terrorism,” said Mr. Prodi. European Union Secretary of Foreign and Immediately upon his return from for third summit attacks on Washington and New York on Security Policy Javier Solana on by Roman Woronowycz September 11 when its Permanent Yalta, President Kuchma first called a Kyiv Press Bureau September 11, issued a statement express- special meeting of the National Security Mission to the United Nations called a ing shock and offering condolences. and Defense Council for the next day and KYIV – Leaders of the European special meeting of the U.N. Security Messrs. Prodi and Solana, who were at Union and Ukraine met in Yalta, Crimea, Council to coordinate global reaction. Symferopol Airport in Crimea on their then went on national television to call For security reasons, the meeting was on September 10-11 for their third annu- way back to Brussels, expressed shock (Continued on page 23) al summit – the first in Ukraine – which held outside the confines of the United had been advertised as a turning point Nations at the mission headquarters of during which relations would move from the Ukrainian delegation in New York. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2003, No.43

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Instructions for new Diversity Visa Lottery — page 3. • Ukrainian American Veterans hold 56th national convention — page 4. • Adrian Karatnycky speaks on Ukraine’s domestic and foreign affairs — page 9. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXI HE No.KRAINIAN 43 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2003 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine HistorianT says UPulitzer awarded Russian-UkrainianW dispute over Tuzla escalates by Roman Woronowycz Yanukovych called for calm and the use of to Duranty should be revoked Kyiv Press Bureau diplomacy to defuse the situation. “We cannot allow this to turn into armed by Andrew Nynka 1932 be revoked, The New York Times KYIV – A diplomatic tussle that began reported. The letter asked the newspaper conflict,” warned Mr. Yanukovych on PARSIPPANY, N.J. – A noted with the construction of a dike by Russia to for its comments on Mr. Duranty’s work. October 21. “We must resolve this at the Columbia University professor of history link the Russian Taman Peninsula with the As part of its review of Mr. Duranty’s negotiating table.” has said in a report – commissioned by Ukrainian island of Tuzla in the Kerch work, The New York Times commis- On October 22 the prime minister’s The New York Times and subsequently Strait escalated to full-blown crisis begin- sioned Dr. von Hagen, an expert on early office announced that Mr. Yanukovych had sent to the Pulitzer Prize Board – that the ning on October 20 when Moscow question canceled a trip to Estonia and would fly 20th century Soviet history, to examine Ukraine’s sovereignty over the tiny island 1931 dispatches of Pulitzer Prize winner nearly all of what Mr. -

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55407 Newsletter #96 December, 2011 — February, 2012 Hours: M-F 10 am to 8 pm RECENTLY RECEIVED AND FORTHCOMING SCIENCE FICTION Sat. 10 am to 6 pm; Sun. Noon to 5 pm Already Received Uncle Hugo's 612-824-6347 Adams, Guy The Men Who Sold the World (Torchwood: PBO)........................ $11.99 Uncle Edgar's 612-824-9984 Augarde, Steve X-Isle (YA).............................................................$9.99 Fax 612-827-6394 E-mail: [email protected] Baum, L. Frank Little Wizard Stories of Oz (Reissue; Kids; Collection of six short stories; includes the Website: www.UncleHugo.com original full-color illustrations)..............................................$14.99 Baxter, Stephen The H-Bomb Girl (1962: In Liverpool, new music is bursting onto the streets, promising to change everything. In Cuba, nuclear tensions are at breaking point, and the end of the world could 31st Anniversary Sale be just days away. Meanwhile, 14-year-old Laura Mann is on the run, hunted by strange forces fighting over the future of humanity).........................................$15.00 December 1 marks Uncle Black, H/Naifeh, T Kind (Good Neighbors #3: YA; Graphic novel).. $12.99 Edgar’s 31st anniversary. Come into Brown, Palmer Beyond the Pawpaw Trees (Anna Lavinia #1: Reissue; Kids). $14.95 Caine, Rachel Last Breath (Morganville Vampires #11: YA)................................$17.99 Uncle Edgar’s or Uncle Hugo’s and save Carey, Janet Lee The Beast of Noor (Noor #1: Kids).......................................$7.99 10% off everything except discount Carey, Mike/Gross, P Leviathan (Unwritten #4: PBO; Full color graphic novel; the mysterious Cabal auditions a new cards, gift certificates, or merchandise assassin and Tom seeks out 'the source'. -

Iveigh Ivelan Iveland Ivelane Ivelant Ivelen Ivelend Ivelent Ivelind Ivelint

Iveigh Ivones Izearde Izzach Izzox Ivelan Ivoomb Izeart Izzack Izzoyd Iveland Ivoombe Izech Izzacke Izzsard Ivelane Ivor Izeck Izzaech Izzude Ivelant Ivors Izerd Izzaeck Izzume Ivelen Ivory Izert Izzaick Izzyck Ivelend Ivvaren Izett Izzaitch Izzyke Ivelent Ivy Iziac Izzake Ivelind Ivye Izick Izzaock Ivelint Ivymey Izitch Izzaox Ivelyn Ivys Izock Izzard Ivelynd Iwadby Izod Izzarde Ivemey Iwardbey Izode Izzarn Ivemmy Iwardby Izoed Izzarne Ivemy Iwardy Izoit Izzart Iveney Iwerdby Izold Izzarte Ivens Iwoodby Izombe Izzat Iver Ix Izon Izzatt Iverach Ixton Izood Izzayck Iverack Iyon Izoode Izzayke Iveragh Iyone Izoold Izzeard Iverake Iyonne Izoomb Izzearde Iverech Izaac Izoombe Izzeart Ivereck Izaach Izord Izzech Iverick Izaack Izould Izzeck Iveritch Izaacs Izoyd Izzerd Iverock Izaacson Izrael Izzert Iverox Izaake Izraeler Izzett Ivers Izach Izraely Izzick Iverson Izack Izreeli Izzitch Ivery Izacke Izsard Izzock Iveryck Izaech Izsarde Izzod Iveryke Izaeck Izsardt Izzode Ives Izaick Izsart Izzoed Iveson Izaitch Izsarte Izzoit Ivet Izake Izseard Izzold Ivett Izaock Izsearde Izzolm Ivetts Izaox Izseart Izzomb Ivey Izard Izserd Izzombe Ivie Izarde Izsert Izzome Ivimey Izarn Izsord Izzone Ivinges Izarne Izude Izzood Ivington Izart Izyck Izzoode Ivinney Izarte Izyke Izzoold Ivins Izat Izzaac Izzoom Ivinson Izatson Izzaach Izzoomb Iviormy Izatt Izzaack Izzoombe Ivison Izayck Izzaacs Izzord Ivombe Izayke Izzaacson Izzould Ivone Izeard Izzaake Izzown Hall of Names by Swyrich © 1999 Swyrich Corporation www.swyrich.com 1-888-468-7686 557 Jackline Jacok