Reading a Medieval Romance in Post-Revolutionary Tehran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum: a Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades One to Eight

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight INTRODUCTION TO THE AGA KHAN MUSEUM The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada is North America’s first museum dedicated to the arts of Muslim civilizations. The Museum aims to connect cultures through art, fostering a greater understanding of how Muslim civilizations have contributed to world heritage. Opened in September 2014, the Aga Khan Museum was established and developed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). Its state-of-the-art building, designed by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, includes two floors of exhibition space, a 340-seat auditorium, classrooms, and public areas that accommodate programming for all ages and interests. The Aga Khan Museum’s Permanent Collection spans the 8th century to the present day and features rare manuscript paintings, individual folios of calligraphy, metalwork, scientific and musical instruments, luxury objects, and architectural pieces. The Museum also publishes a wide range of scholarly and educational resources; hosts lectures, symposia, and conferences; and showcases a rich program of performing arts. Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight Patricia Bentley and Ruba Kana’an Written by Patricia Bentley, Education Manager, Aga Khan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Museum, and Ruba Kana’an, Head of Education and Scholarly reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any Programs, Aga Khan Museum, with contributions by: form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers. -

Irreverent Persia

Irreverent Persia IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES Poetry expressing criticism of social, political and cultural life is a vital integral part of IRREVERENT PERSIA Persian literary history. Its principal genres – invective, satire and burlesque – have been INVECTIVE, SATIRICAL AND BURLESQUE POETRY very popular with authors in every age. Despite the rich uninterrupted tradition, such texts FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE TIMURID PERIOD have been little studied and rarely translated. Their irreverent tones range from subtle (10TH TO 15TH CENTURIES) irony to crude direct insults, at times involving the use of outrageous and obscene terms. This anthology includes both major and minor poets from the origins of Persian poetry RICCARDO ZIPOLI (10th century) up to the age of Jâmi (15th century), traditionally considered the last great classical Persian poet. In addition to their historical and linguistic interest, many of these poems deserve to be read for their technical and aesthetic accomplishments, setting them among the masterpieces of Persian literature. Riccardo Zipoli is professor of Persian Language and Literature at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, where he also teaches Conceiving and Producing Photography. The western cliché about Persian poetry is that it deals with roses, nightingales, wine, hyperbolic love-longing, an awareness of the transience of our existence, and a delicate appreciation of life’s fleeting pleasures. And so a great deal of it does. But there is another side to Persian verse, one that is satirical, sardonic, often obscene, one that delights in ad hominem invective and no-holds barred diatribes. Perhaps surprisingly enough for the uninitiated reader it is frequently the same poets who write both kinds of verse. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

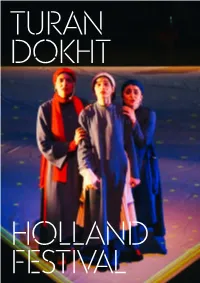

Turan-Dokht-Programme.Pdf

TURAN DOKHT HOLLAND FESTIVAL TURAN DOKHT Aftab Darvishi Miranda Lakerveld Nilper Orchestra thanks to production partner patron coproduction CONTENT Info & context Credits Synopsis Notes A conversation with Miranda Lakerveld About the artists Friends Holland Festival 2019 Join us Colophon INFO CONTEXT date & starting time introduction Wed 5 June 2019, 8.30 pm by Peyman Jafari Thu 6 June 2019, 8.30 pm 7.45 pm venue Hamid Dabashi – Persian culture on Muziekgebouw The Global Scene Thu 6 Juni, 4 pm running time Podium Mozaïek 1 hour 20 minutes no interval language Farsi and Italian with English and Dutch surtitles CREDITS composition production Aftab Darvishi World Opera Lab, Jasper Berben libretto, direction with support of Miranda Lakerveld Fonds Podiumkunsten, Gieskes-Strijbis Fonds, Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst, conductor Nederlandse Ambassade Tehran Navid Gohari world premiere video 24 February 2019 Siavash Naghshbandi Azadi Tower, Tehran light Turan Dokht is inspired by the Haft Bart van den Heuvel Peykar of Nizami Ganjavi and Turandot by Giacomo Puccini. The fragments of costumes Puccini’s Turandot are used with kind per- Nasrin Khorrami mission of Ricordi Publishing House. dramaturgy, text advice All the flights that are made for this Asghar Seyed-Gohrab project are compensated for their CO2 emissions. vocals Ekaterina Levental (Turan Dokht), websites Arash Roozbehi (The unknown prince), World Opera Lab Sarah Akbari, Niloofar Nedaei, Miranda Lakerveld Tahere Hezave Aftab Darvishi acting musicians Yasaman Koozehgar, Yalda Ehsani, Mahsa Rahmati, Anahita Vahediardekani music performed by Behzad Hasanzadeh, voice/kamanche Mehrdad Alizadeh Veshki, percussion Nilper Orchestra SYNOPSIS The seven beauties from Nizami’s Haft Peykar represent the seven continents, the seven planets and the seven colours. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28 Traces of Time The Image of the Islamic Revolution, the Hero and Martyrdom in Persian Novels Written in Iran and in Exile Behrooz Sheyda ABSTRACT Sheyda, B. 2016. Traces of Time. The Image of the Islamic Revolution, the Hero and Martyrdom in Persian Novels Written in Iran and in Exile. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28. 196 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-9577-0 The present study explores the image of the Islamic Revolution, the concept of the hero, and the concept of martyrdom as depicted in ten post-Revolutionary Persian novels written and published in Iran compared with ten post-Revolutionary Persian novels written and published in exile. The method is based on a comparative analysis of these two categories of novels. Roland Barthes’s structuralism will be used as the theoretical tool for the analysis of the novels. The comparative analysis of the two groups of novels will be carried out within the framework of Foucault’s theory of discourse. Since its emergence, the Persian novel has been a scene for the dialogue between the five main discourses in the history of Iran since the Constitutional Revolution; this dialogue, in turn, has taken place within the larger framework of the dialogue between modernity and traditionalism. The main conclusion to be drawn from the present study is that the establishment of the Islamic Republic has merely altered the makeup of the scene, while the primary dialogue between modernity and traditionalism continues unabated. This dialogue can be heard in the way the Islamic Republic, the hero, and martyrdom are portrayed in the twenty post-Revolutionary novels in this study. -

Problems of Muslim Belief in Azerbaijan: Historical and Modern Realities

ISSN 2707-4013 © Nariman Gasimoglu СТАТТІ / ARTICLES e-mail: [email protected] Nariman Gasimoglu. Problems of Muslim Belief іn Azerbaijan: Historical аnd Modern Realities. Сучасне ісламознавство: науковий журнал. Острог: Вид-во НаУОА, 2020. DOI: 10.25264/2707-4013-2020-2-12-17 № 2. C. 12–17. Nariman Gasimoglu PROBLEMS OF MUSLIM BELIEF IN AZERBAIJAN: HISTORICAL AND MODERN REALITIES Religiosity in Azerbaijan, the country where vast majority of population are Muslims, has many signs different to what is practiced in other Muslim countries. This difference in the first place is related to the historically established religious mentality of Azerbaijanis. Worth noting is that history of this country with its Shia Muslims majority and Sunni Muslims minority have registered no serious incidents or confessional conflicts and clashes either on the ground of inter-sectarian confrontation or between Muslim and non-Muslim population. Azerbaijan has never had anti-Semitism either; there has been no fact of oppression of Jewish people living in Azerbaijan for many centuries. One of the interesting historic facts is that Molokans (ethnic Russians) who have left Tsarist Russia when challenged by religious persecution and found asylum in neighborhoods of Muslim populated villages of Azerbaijan have been living there for about two hundred years and never faced problems as a religious minority. Besides historical and political reasons, this should be related to tolerance in the religious mentality of Azerbaijanis as well. Features of religion in Azerbaijan: historical context Most of the people living in Azerbaijan were devoted to Tengriism (Tengriism had the most important place in the old belief system of ancient Turks), Zoroastrianism and Christianity before they embraced Islam. -

Love Me, Love Me Not Contemporary Art from Azerbaijan and Its Neighbours Collateral Event for the 55Th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale Di Venezia

Love Me, Love Me Not Contemporary Art from Azerbaijan and its Neighbours Collateral Event for the 55th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia Moshiri and Slavs and Tatars, amongst selected artists. Faig Ahmed, Untitled, 2012. Thread Installation, dimensions variable Love Me, Love Me Not is an unprecedented exhibition of contemporary art from Azerbaijan and its neighbours, featuring recent work by 17 artists from Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkey, Russia, and Georgia. Produced and supported by YARAT, a not-for-profit contemporary art organisation based in Baku, and curated by Dina Nasser-Khadivi, the exhibition will be open to the public from 1st June until 24 th November 2013 at Tesa 100, Arsenale Nord, at The 55th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia. Artists featured: Ali Hasanov (Azerbaijan) Faig Ahmed (Azerbaijan) Orkhan Huseynov (Azerbaijan) Rashad Alakbarov (Azerbaijan) Sitara Ibrahimova (Azerbaijan) Afruz Amighi (Iran) Aida Mahmudova (Azerbaijan) Taus Makhacheva (Russia) Shoja Azari (Iran) Farhad Moshiri (Iran) Rashad Babayev (Azerbaijan) Farid Rasulov (Azerbaijan) Mahmoud Bakhshi (Iran) Slavs and Tatars (‘Eurasia’) Ali Banisadr (Iran) Iliko Zautashvili (Georgia) "Each piece in this exhibition has a role of giving the viewers at least one new perspective on the nations represented in this pavilion, with the mere intent to give a better understanding of the area that is being covered. Showcasing work by these artists in a single exhibition aims to, ultimately, question how we each perceive history and geography. Art enables dialogue and the Venice Biennale has proven to be the best arena for cultural exchange." explains curator Dina Nasser-Khadivi. The exhibition offers a diverse range of media and subject matter, with video, installation and painting all on show. -

The Academic Resume of Dr. Gholamhossein Gholamhosseinzadeh

The Academic Resume of Dr. Gholamhossein Gholamhosseinzadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature in Tarbiat Modarres University Academic Background Degree The end date Field of Study University Ferdowsi Persian Language University of ١٩٧٩/٤/٤ BA and Literature Mashhad Persian Language Tarbiat Modarres and Literature University ١٩٨٩/٢/٤ MA Persian Language Tarbiat Modarres and Literature University ١٩٩٥/٣/١٥ .Ph.D Articles Published in Scientific Journals Year of Season of Row Title Publication Publication Explaining the Reasons for Explicit Adoptions Summer ٢٠١٨ of Tazkara-Tul-Aulia from Kashif-Al-Mahjoub ١ in the Sufis Karamat Re-Conjugation of Single Paradigms of Middle Spring ٢٠١٧ Period in the Modern Period (Historical ٢ Transformation in Persian Language) ٢٠١٧ Investigating the Effect of the Grammatical Elements and Loan Words of Persian Language Spring ٣ on Kashmiri Language ٢٠١٧ The Course of the Development and Spring Categorization of the Iranian Tradition of ٤ Writing Political Letter of Advice in the World Some Dialectal Elements in Constructing t he Spring ٢٠١٦ ٥ Verbs in the Text of Creation ٢٠١٦ The Coding and the Aspect: Two Distinctive Fall ٦ ١ Year of Season of Row Title Publication Publication Factors in the Discourse Stylistics of Naser Khosrow’s Odes ٢٠١٦ Conceptual Metaphor: Convergence of Summer ٧ Thought and Rhetoric in Naser Khosrow's Odes ٢٠١٦ A Comparative Study of Linguistic and Stylistic Features of Samak-E-Ayyar, Hamzeh- Fall ٨ Nameh and Eskandar-Nameh ٢٠١٦ The Effect of Familiarity with Old Persian -

Nizami Gəncəvi Yaradıcılığında Coğrafi Adlar

1 Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores. http://www.dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/ Año: VII Número: Edición Especial Artículo no.:88 Período: Diciembre, 2019. TÍTULO: Nombres geográficos en las obras de Nizami Ganjavi. AUTOR: 1. Ph.D. Bayram Apoev. RESUMEN: El artículo analiza los nombres geográficos que se reflejan en Hamsa por Nizami Ganjavi. Como resultado del estudio de los nombres geográficos, se compiló una tabla. Esta tabla cubre 157 nombres geográficos. Se reveló que la mayoría de estos nombres (125) se dieron en Iskendernam. Un análisis de estos nombres geográficos es evidencia de que el brillante pensador Nizami estudió profundamente la literatura griega y árabe antigua y las obras de geógrafos antiguos y conocía de cerca la apariencia geográfica del globo. PALABRAS CLAVES: Nizami Ganjavi, poeta azerbaiyano, nombres geográficos. TITLE: Geographical names in the works of Nizami Ganjavi. AUTHOR. 1. Ph.D. Bayram Apoev. ABSTRACT: The article analyzes the geographical names that are reflected in Hamsa by Nizami Ganjavi. As a result of the study of geographical names, a table was compiled. This table covers 157 geographical names. It was revealed that most of these names (125) were given in Iskendernam. An analysis of these geographical names is evidence that the brilliant thinker Nizami 2 deeply studied the ancient Greek and Arabic literature and the works of ancient geographers and was closely acquainted with the geographical appearance of the globe. KEY WORDS: Nizami Ganjavi, Azerbaijani poet, geographical names. INTRODUCTION. Nizami, who was “a genius in the true sense of the word” (Y. Bertels, 1962), “the highest mountain of human ideas”, “goddess of the artistic word”, “owner of encyclopedic intelligence” and the phenomenon of human perception at all times and artistic thinking stands at the highest point of view.