Afghanistan Inc.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The News Media Industry Defined

Spring 2006 Industry Study Final Report News Media Industry The Industrial College of the Armed Forces National Defense University Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. 20319-5062 i NEWS MEDIA 2006 ABSTRACT: The American news media industry is characterized by two competing dynamics – traditional journalistic values and market demands for profit. Most within the industry consider themselves to be journalists first. In that capacity, they fulfill two key roles: providing information that helps the public act as informed citizens, and serving as a watchdog that provides an important check on the power of the American government. At the same time, the news media is an extremely costly, market-driven, and profit-oriented industry. These sometimes conflicting interests compel the industry to weigh the public interest against what will sell. Moreover, several fast-paced trends have emerged within the industry in recent years, driven largely by changes in technology, demographics, and industry economics. They include: consolidation of news organizations, government deregulation, the emergence of new types of media, blurring of the distinction between news and entertainment, decline in international coverage, declining circulation and viewership for some of the oldest media institutions, and increased skepticism of the credibility of “mainstream media.” Looking ahead, technology will enable consumers to tailor their news and access it at their convenience – perhaps at the cost of reading the dull but important stories that make an informed citizenry. Changes in viewer preferences – combined with financial pressures and fast paced technological changes– are forcing the mainstream media to re-look their long-held business strategies. These changes will continue to impact the media’s approach to the news and the profitability of the news industry. -

Mythical State the Aesthetics and Counter-Aesthetics of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 10 (2017) 255–271 MEJCC brill.com/mjcc Mythical State The Aesthetics and Counter-Aesthetics of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria Nathaniel Greenberg George Mason University, va, usa [email protected] Abstract In the summer of 2014, on the heels of the declaration of a ‘caliphate’ by the leader of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (isis), a wave of satirical production depicting the group flooded the Arab media landscape. Seemingly spontaneous in some instances and tightly measured in others, the Arab comedy offensive paralleled strategic efforts by the United States and its allies to ‘take back the Internet’ from isis propagandists. In this essay, I examine the role of aesthetics, broadly, and satire in particular, in the creation and execution of ‘counter-narratives’ in the war against isis. Drawing on the pioneering theories of Fred Forest and others, I argue that in the age of digital reproduction, truth-based messaging campaigns underestimate the power of myth in swaying hearts and minds. As a modus of expression conceived as an act of fabrication, satire is poised to counter myth with myth. But artists must balance a very fine line. Keywords isis – isil – daish – daesh – satire – mythology – counternarratives – counter- communications – terrorism – takfir Introduction In late February 2016, Capitol Hill was abuzz with the announcement by State Department officials that they were working on a major joint public-private initiative to ‘“take back the Internet” from increasingly prolific jihadist sup- porters’.1The campaign, ‘Madison Valleywood’,was to include both the disman- 1 The phrase is drawn from the introductory remarks to Monika Bickert’s presentation at the © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2017 | doi: 10.1163/18739865-01002009Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 03:29:38AM via free access 256 greenberg tling of propaganda on social media sites controlled by the Islamic State and the creation of ‘counter-narratives’ to roll back the effect of the group’s propaganda. -

Supply Chain Operations Audit

Building 243 University Campus Cranfield Bedford MK43 0AL Tel: +44 (0)1234 750323 Fax: +44 (0)1234 752040 www.scp-uk.co.uk Supply Chain Operations Audit by Dr. David Lascelles, Supply Chain Planning UK Limited High Impact Supply Chains Supply chain excellence has a real impact on business strategy. Supply chain management is a high impact mission that goes to the roots of a company’s very competitiveness. High-impact supply chains win market share and customer loyalty, create shareholder value, extend the strategic capability and reach of the business. Independent research shows that excellent supply chain management can yield: · 25-50% reduction in total supply chain costs · 25-60% reduction in inventory holding · 25-80% increase in forecast accuracy · 30-50% improvement in order-fulfilment cycle time · 20% increase in after-tax free cash flows That’s what we mean by high-impact. Does a high-impact supply chain leverage your business enterprise? Five Critical Success Factors Building a high-impact supply chain represents one of the most exciting opportunities to create value – and one of the most challenging. The key to success lies in knowing which levers to pull. Our research, together with practical experience, reveals that high-impact supply chains are, essentially, a function of five critical success factors: 1. A clear strategy: for the entire supply chain, tuned to market opportunities and focussed on customer service needs. 2. An integrated organisation structure: enabling the supply chain to operate as a single synchronised entity. 3. Excellent processes: for implementing the strategy, embracing all plan- source-make-deliver operations. -

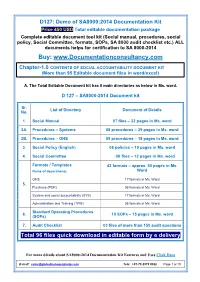

SA 8000:2014 Documents with Manual, Procedures, Audit Checklist

D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Chapter-1.0 CONTENTS OF SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY DOCUMENT KIT (More than 95 Editable document files in word/excel) A. The Total Editable Document kit has 8 main directories as below in Ms. word. D 127 – SA8000-2014 Document kit Sr. List of Directory Document of Details No. 1. Social Manual 07 files – 22 pages in Ms. word 2A. Procedures – Systems 08 procedures – 29 pages in Ms. word 2B. Procedures – OHS 09 procedures – 18 pages in Ms. word 3. Social Policy (English) 08 policies – 10 pages in Ms. word 4. Social Committee 08 files – 12 pages in Ms. word Formats / Templates 43 formats – approx. 50 pages in Ms. Name of departments Word OHS 17 formats in Ms. Word 5. Purchase (PUR) 05 formats in Ms. Word System and social accountability (SYS) 17 formats in Ms. Word Administration and Training (TRG) 05 formats in Ms. Word Standard Operating Procedures 6. 10 SOPs – 15 pages in Ms. word (SOPs) 7. Audit Checklist 03 files of more than 150 audit questions Total 96 files quick download in editable form by e delivery For more détails about SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Features and Uses Click Here E-mail: [email protected] Tele: +91-79-2979 5322 Page 1 of 10 D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Part: B. -

Afghan-American Diaspora in Post-Conflict Peacebuilding and Reconstruction

The Reverse Brain Drain: Afghan-American Diaspora in Post-Conflict Peacebuilding and Reconstruction OUTLINE: Abstract I. Introduction Background Definition III. Mechanisms to engage diaspora IV. Challenges and constraints V. Sustaining momentum The loss of human resources that Afghanistan experienced following the Soviet invasion of 1979 is often referred to as the 'brain drain'. This paper postulates that a similar but 'reverse brain drain' is currently in progress as former Afghan nationals return to the country in droves to assist in the rebuilding of Afghanistan. While remaining aware of risks and challenges, the potential for building the capacity of civil society and the private sector is at its peak. This thesis is examined within the context of Afghan culture, opportunities for personal and professional growth in the United States for the diaspora, and how these positive externalities can be harnessed to bring the maximal value added to the reconstruction of Afghanistan. Individual and group behavior are as important an element of peace building as are education or skills level, and by behaving professionally and collectively, the Afghan-American diaspora can best influence policy planning and implementation of reconstruction in Afghanistan. 1 This paper is dedicated to the memory of Farhad Ahad , a committed and energetic activist and professional, a true role model for the Afghan-American diaspora who gave his life for the economic development of his country. I. Introduction Background Twenty-three years ofACKU war have left Afghanistan devastated. Following the brutal Soviet invasion, the country was further ravaged by fundamentalist warring parties supported by neighboring countries and international interests. -

Guide to Inspections of Quality Systems

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION GUIDE TO INSPECTIONS OF QUALITY SYSTEMS 1 August 19991 2 Guide to Inspections of Quality Systems This document was developed by the Quality System Inspec- tions Reengineering Team Members Office of Regulatory Affairs Rob Ruff Georgia Layloff Denise Dion Norm Wong Center for Devices and Radiological Health Tim Wells – Team Leader Chris Nelson Cory Tylka Advisors Chet Reynolds Kim Trautman Allen Wynn Designed and Produced by Malaka C. Desroches 3 Foreword This document provides guidance to the FDA field staff on a new inspectional process that may be used to assess a medical device manufacturer’s compliance with the Quality System Regulation and related regulations. The new inspectional process is known as the “Quality System Inspection Technique” or “QSIT”. Field investigators may conduct an ef- ficient and effective comprehensive inspection using this guidance material which will help them focus on key elements of a firm’s quality system. Note: This manual is reference material for investi- gators and other FDA personnel. The document does not bind FDA and does not confer any rights, privi- leges, benefits or immunities4 for or on any person(s). Table of Contents Performing Subsystem Inspections. 7 Pre-announced Inspections. ..13 Getting Started. .15 Management Controls. .17 Inspectional Objectives 18 Decision Flow Chart 19 Narrative 20 Design Controls. .31 Inspectional Objectives 32 Decision Flow Chart 33 Narrative 34 Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA). .47 Inspectional Objectives 48 Decision Flow Chart 49 Narrative 50 Medical Device Reporting 61 Inspectional Objectives 62 Decision Flow Chart 63 Narrative 64 Corrections & Removals 67 Inspectional Objectives 68 Decision Flow Chart 69 Narrative 70 Medical Device Tracking 73 Inspectional Objectives 74 Decision Flow Chart 75 Narrative 76 Production and Process Controls (P&PC). -

Social Accounting: a Practical Guide for Small-Scale Community Organisations

Social Accounting: A Practical Guide for Small-Scale Community Organisations Social Accounting: A Practical Guide for Small Community Organisations and Enterprises Jenny Cameron Carly Gardner Jessica Veenhuyzen Centre for Urban and Regional Studies, The University of Newcastle, Australia. Version 2, July 2010 This page is intentionally blank for double-sided printing. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………..1 How this Guide Came About……………………………………………………2 WHAT IS SOCIAL ACCOUNTING?………………………………………………..3 Benefits.………………………………………………………………………....3 Challenges.……………………………………………………………………....4 THE STEPS………………………………………...…………………………………..5 Step 1: Scoping………………………………….………………………………6 Step 2: Accounting………………………………………………………………7 Step 3: Reporting and Responding…………………….……………………….14 APPLICATION I: THE BEANSTALK ORGANIC FOOD…………………….…16 APPLICATION II: FIG TREE COMMUNITY GARDEN…………………….…24 REFERENCES AND RESOURCES…………………………………...……………33 Acknowledgements We would like to thank The Beanstalk Organic Food and Fig Tree Community Garden for being such willing participants in this project. We particularly acknowledge the invaluable contribution of Rhyall Gordon and Katrina Hartwig from Beanstalk, and Craig Manhood and Bill Roberston from Fig Tree. Thanks also to Jo Barraket from the The Australian Centre of Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies, Queensland University of Technology, and Gianni Zappalà and Lisa Waldron from the Westpac Foundation for their encouragement and for providing an opportunity for Jenny and Rhyall to present a draft version at the joint QUT and Westpac Foundation Social Evaluation Workshop in June 2010. Thanks to the participants for their feedback. Finally, thanks to John Pearce for introducing us to Social Accounting and Audit, and for providing encouragement and feedback on a draft version. While we have adopted the framework and approach to suit the context of small and primarily volunteer-based community organisations and enterprises, we hope that we have remained true to the intentions of Social Accounting and Audit. -

11. Conflicts of Interest

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Anti-Bribery Guidance Chapter 11 Transparency International (TI) is the world’s leading non-governmental anti-corruption organisation. With more than 100 chapters worldwide, TI has extensive global expertise and understanding of corruption. Transparency International UK (TI-UK) is the UK chapter of TI. We raise awareness about corruption; advocate legal and regulatory reform at national and international levels; design practical tools for institutions, individuals and companies wishing to combat corruption; and act as a leading centre of anti-corruption expertise in the UK. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank DLA Piper, FTI Consulting and the members of the Expert Advisory Committee for advising on the development of the guidance: Andrew Daniels, Anny Tubbs, Fiona Thompson, Harriet Campbell, Julian Glass, Joshua Domb, Sam Millar, Simon Airey, Warwick English and Will White. Special thanks to Jean-Pierre Mean and Moira Andrews. Editorial: Editor: Peter van Veen Editorial staff: Alice Shone, Rory Donaldson Content author: Peter Wilkinson Project manager: Rory Donaldson Publisher: Transparency International UK Design: 89up, Jonathan Le Marquand, Dominic Kavakeb Launched: October 2017 © 2018 Transparency International UK. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in parts is permitted providing that full credit is given to Transparency International UK and that any such reproduction, in whole or in parts, is not sold or incorporated in works that are sold. Written permission must be sought from Transparency International UK if any such reproduction would adapt or modify the original content. If any content is used then please credit Transparency International UK. Legal Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. -

Business Ethics: a Panacea for Reducing Corruption and Enhancing National Development

Nigerian Journal of Business Education (NIGJBED) Volume 5 No.2, 2018 BUSINESS ETHICS: A PANACEA FOR REDUCING CORRUPTION AND ENHANCING NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AKPANOBONG, UYAI EMMANUEL, Ph.D. Department of Vocational Education, Faculty of Education, University of Uyo Email:[email protected] Abstract In recent times there are scandals of unethical behaviours, corrupt practices, lack of accountability and transparency amongst public officials, political office holders, business managers and employees in the country. Therefore, there is an urgent need for public sector institutions to strengthen the ethics of their profession, integrity, honesty, transparency, confidentiality, and accountability in the public service. The paper further attempt to discuss the need for business ethics and some practices and behaviours which undermined the ethical behaviours of public official with strong emphasis on corruptions causes and preventions, conflicts of interest, consequences of unethical behaviour and resources management. The paper also outlined some measures on how to combat the evil called corruption in public service and business organizations. It is concluded that if all measures are taken into consideration the National Development may be achieved. Keywords: Ethics, unethical, transparency, accountability, corruption. Introduction In every business organization, there must be a laid down rules, values norms, order and other guiding principles which may be in form of ethics. The essence of this is to guide both the employer and the employees in achieving the organizational goals and at the same time help in checks and balances. Luanne (2017 saw ethics as the principles and values an individual uses to govern his activities and decisions. Therefore, Business Ethics could be described as that aspect of corporate governance that has to do with the moral values of managers encouraging them to be transparent in business dealing (Chienweike, 2010). -

Sudan Transitional Environment Program Programmatic Environmental Assessment (Pea) of Road Rehabilitation Activities in Southern Sudan

SUDAN TRANSITIONAL ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM PROGRAMMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (PEA) OF ROAD REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES IN SOUTHERN SUDAN FINAL REPORT June 2006 This publication was produced for the United States Agency for International Development.. It was prepared by Thomas M. Catterson, IRG; Karen Menczer, The Cadmus Group; Jacob Marial Maker, GOSS Ministry of Transport and Roads; and Victor Wurda LoTombe, GOSS Ministry of Environment, Wildlife Conservation and Tourism. COVER PHOTO Rehabilitated Roads–Making a Real Difference in Southern Sudan Photo by: T. Catterson/IRG SUDAN TRANSITIONAL ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM PROGRAMMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (PEA) OF ROAD REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES IN SOUTHERN SUDAN FINAL REPORT International Resources Group Government of Southern Sudan Government of Southern Sudan 1211 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 700 Ministry of Transport & Roads Ministry of Environment, Washington, DC 20036 Wildlife Conservation and Tourism 202-289-0100 Fax 202-289-7601 www.irgltd.com DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS Acronyms ............................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 5 Background to the PEA ....................................................................................... 11 Description -

South Sudan Corridor Diagnostic Study and Action Plan

South Sudan Corridor Diagnostic Study and Action Plan Final Report September 2012 This publication was produced by Nathan Associates Inc. for review by the United States Agency for International Development under the USAID Worldwide Trade Capacity Building (TCBoost) Project. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. South Sudan Corridor Diagnostic Study and Action Plan Final Report SUBMITTED UNDER Contract No. EEM-I-00-07-00009-00, Order No. 2 SUBMITTED TO Mark Sorensen USAID/South Sudan Cory O’Hara USAID EGAT/EG Office SUBMITTED BY Nathan Associates Inc 2101 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1200 Arlington, Virginia 22201 703.516.7700 [email protected] [email protected] DISCLAIMER This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents Acronyms v Executive Summary vii 1. Introduction 1 Study Scope 1 Report Organization 3 2. Corridor Infrastructure 5 South Sudan Corridor Existing Infrastructure and Condition 5 3. Corridor Performance 19 Performance Data: Nodes and Links 19 Overview of South Sudan Corridor Performance 25 South Sudan Corridor Cost and Time Composition 26 Interpretation of Results for South Sudan Corridor 29 4. Legal and Regulatory Framework 33 Overview of Legal System 33 National Transport Policy 36 Transport Legal and Regulatory Framework Analysis 40 Customs and Taxation: Legal and Regulatory Framework Analysis 53 5. -

Social Accountability International (SAI) and Social Accountability Accreditation Services (SAAS)

Social Accountability International (SAI) and Social Accountability Accreditation Services (SAAS) Profile completed by Erika Ito, Kaylena Katz, and Chris Wegemer Last edited June 25, 2014 History of organization In 1996, the Social Accountability International (SAI) Advisory Board was created to establish a set of workplace standards in order to “define and verify implementation of ethical workplaces.” This was published as the first manifestation of SA8000 in 1997.1 The SAI Advisory Board was created by the Council on Economic Priorities (CEP) in response to public concern about working conditions abroad. Until the summer of 2000, this new entity was known as the Council on Economic Priorities Accreditation Agency, or CEPAA.2 Founded in 1969, the Council on Economic Priorities, a largely corporatefunded nonprofit research organization, was “a public service research organization dedicated to accurate and impartial analysis of the social and environmental records of corporations” and aimed to “to enhance the incentives for superior corporate social and environmental performance.”3 The organization was known for its corporate rating system4 and its investigations of the US defense industry.5 Originally, SAI had both oversight of the SA8000 standard and accreditation of auditors. In 2007, the accreditation function of SAI was separated from the organization, forming Social Accountability Accreditation Services (SAAS).6 The operations and governance of SAI and SAAS remain inexorably intertwined; SAI cannot function without the accreditation services of SAAS, and SAAS would not exist without SAI’s maintenance of the SA8000 standards and training guidelines. They see each other as a “related body,” which SAAS defines as “a separate legal entity that is linked by common ownership or contractual arrangements to the accreditation body.”7 Because of this interdependence, they are often treated by activists and journalists as a single entity.