The Genesis of Mr. Isaacs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermaphrodite Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams

Philosophies of Sex Etching of Julia Ward Howe. By permission of The Boston Athenaeum hilosophies of Sex PCritical Essays on The Hermaphrodite EDITED BY RENÉE BERGLAND and GARY WILLIAMS THE OHIO State UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Philosophies of sex : critical essays on The hermaphrodite / Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1189-2 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1189-5 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9290-7 (cd-rom) 1. Howe, Julia Ward, 1819–1910. Hermaphrodite. I. Bergland, Renée L., 1963– II. Williams, Gary, 1947 May 6– PS2018.P47 2012 818'.409—dc23 2011053530 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Minion Pro and Scala Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction GARY Williams and RENÉE Bergland 1 Foreword Meeting the Hermaphrodite MARY H. Grant 15 Chapter One Indeterminate Sex and Text: The Manuscript Status of The Hermaphrodite KAREN SÁnchez-Eppler 23 Chapter Two From Self-Erasure to Self-Possession: The Development of Julia Ward Howe’s Feminist Consciousness Marianne Noble 47 Chapter Three “Rather Both Than Neither”: The Polarity of Gender in Howe’s Hermaphrodite Laura Saltz 72 Chapter Four “Never the Half of Another”: Figuring and Foreclosing Marriage in The Hermaphrodite BetsY Klimasmith 93 vi • Contents Chapter Five Howe’s Hermaphrodite and Alcott’s “Mephistopheles”: Unpublished Cross-Gender Thinking JOYCE W. -

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION of PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School H

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School HONORS Date September 16, 2013 Course No. or level HNRS 270-279 Title HONORS SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES Semester hours 3 Clock hours: Lecture 3 Laboratory 0 Prerequisites Membership in FMU Honors, or permission of Honors Director Enrollment expectation 15 Indicate any course for which this course is a (an) Modification N/A Substitute N/A Alternate N/A Name of person preparing course description: Jon Tuttle Department Chairperson’s /Dean’s Signature _______________________________________ Date of Implementation Fall 2014 Date of School/Department approval: September 13, 2013 Catalog description: 270-279 SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (3) (Prerequisite: membership in FMU Honors or permission of Honors Director.) Course topics may be interdisciplinary and cover innovative, non-traditional topics within the Behavioral Sciences. May be taken for General Education credit as an Area 4: Humanities/Social Sciences elective. May be applied as elective credit in applicable major with permission of chair or dean. Purpose: 1. For Whom (generally?): FMU Honors students, also others students with permission of instructor and Honors Director 2. What should the course do for the student? HNRS 270-279 will offer FMU Honors members enhanced learning options within the Behavioral Sciences beyond the common undergraduate curriculum and engage potential majors with unique, non-traditional topics. Teaching method/textbook and materials planned: Lecture, -

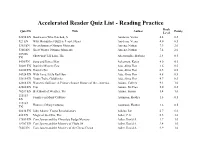

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

Influence of Cavity Availability on Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Group Size

Wilson Bulletin, 110(l), 1998, pp. 93-99 INFLUENCE OF CAVITY AVAILABILITY ON RED-COCKADED WOODPECKER GROUP SIZE N. ROSS CARRIE,,*‘ KENNETH R. MOORE, ’ STEPHANIE A. STEPHENS, ’ AND ERIC L. KEITH ’ ABSTRACT-The availability of cavities can determine whether territories are occupied by Red-cockaded Woodpeckers (Picoides borealis). However, there is no information on whether the number of cavities can influence group size and population stability. We compared group size between 1993 and 1995 in 33 occupied cluster sites that were provisioned with artificial cavities. The number of groups with breeding pairs increased from 22 (67.7%) in 1993 to 28 (93.3%) in 1995. Most breeding males remained in the natural cavities that they had excavated and occupied prior to cavity provisioning in the cluster while breeding females and helpers used artificial cavities extensively. Active cluster sites provisioned with artificial cavities had larger social groups in 1995 (3 = 2.70, SD = 1.42) than in 1993 (3 = 2.00, SD = 0.94; Z = -2.97, P = 0.003). The number of suitable cavities per cluster was positively correlated with the number of birds per cluster (rJ = 0.42, P = 0.016). The number of inserts per cluster was positively correlated with the change in group size between 1993 and 1995 (r, = 0.49, P = 0.004). Our observations indicate that three or four suitable cavities should be maintained uer cluster to stabilize and/or increase Red-cockaded Woodpecker populations. Received 3 March 1997, accepted 57 Oct. 1997. The Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides numbers of old-growth trees for cavity exca- borealis) is an endangered species endemic to vation. -

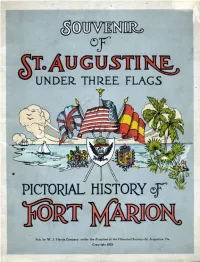

St. Augustine Under Three Flags

SOUVENIR ST.AUGUSTINE UNDER THREE FLAGS PICTORIAL HISTORY OF Pub. by W. J. Harris Company, under the Auspices of the Historical Society—St. Augustine, Fla. Copyright 1925 . PREFACE In this work we have attempted a brief summary of the important events connected with the history of St. Augus- tine and in so doing we must necessarily present the more important facts connected with the history of Fort Marion. The facts and dates contained herein are in accordance with the best authority obtainable. The Historical Society has a large collection of rare maps and books in its Library, one of the best in the State ; the Public Library has also many books on the history of Florida. The City and County records (in English) dating from 1821 contain valuable items of history, as at this date St. Johns County comprised the whole state of Florida east of the Suwannee River and south of Cow's Ford, now the City of Jacksonville. The Spanish records, with a few exceptions, are now in the city of Tallahassee, Department of Agriculture ; the Manuscript Department, Library of Congress, Washington. D. C. and among the "Papeles de Cuba" Seville, Spain. Copies of some very old letters of the Spanish Governors. with English translations, have been obtained by the Historical Society. The Cathedral Archives date from 1594 to the present day. To the late Dr. DeWitt Webb, founder, and until his death, President of the St. Augustine Institute of Science and Historical Society, is due credit for the large number of maps and rare books collected for the Society; the marking and preservation of many historical places ; and for data used in this book. -

One Hundred Nineteenth Commencement

ONE HUNDRED NINETEENTH COMMENCEMENT FRIDAY, MAY 8, 2015 LITTLEJOHN COLISEUM 9:30 A.M. 2:30 P.M. 6:30 P.M. ORDER OF CEREMONIES (Please remain standing for the processional, posting of colors, and invocation.) POSTING OF COLORS Pershing Rifles INVOCATION Sydney J M Nimmons, Student Representative (9:30 A.M. ceremony) Katy Beth Culp, Student Representative (2:30 P.M. ceremony) Corbin Hunter Jenkins, Student Representative (6:30 P.M. ceremony) INTRODUCTION OF TRUSTEES President James P Clements RECOGNITION OF THE DEANS OF THE COLLEGES Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost Robert H Jones CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREE President James P Clements CONFERRING OF DEGREES AND DELIVERY OF DIPLOMAS President James P Clements RECOGNITION AND PRESENTATION OF AWARDS Norris Medal Algernon Sydney Sullivan Awards Alumni Master Teacher Award Faculty Scholarship Award Haleigh Marcolini, Soloist Clemson University Brass Quintet, Instrumentation Dr. Mark A McKnew, University Marshal CEREMONIAL MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Haleigh Marcolini, Soloist David H Wilkins, Chair .............................Greenville, SC Clemson University Brass Quintet, Instrumentation John N McCarter, Jr., Vice Chair ...............Columbia, SC David E Dukes ............................................Columbia, SC Prelude Leon J Hendrix, Jr. ............................... Kiawah Island, SC Various Marches and Processionals Ronald D Lee .....................................................Aiken, SC Louis B Lynn ...............................................Columbia, -

Astillo De Sanmarcos NATIONAL MONUMENT Astillo Desan Marcos NATIONAL MONUMENT U

astillo de SanMarcos NATIONAL MONUMENT astillo deSan Marcos NATIONAL MONUMENT U. S. Department of the Interior, J. A. Krug, Secretary National Park Service, Newton D. Drury, Director Castillo de San Marcos, in St. Augustine, Fla., was built 1672-1756 by Spain and was their northernmost military fortification on the Atlantic coast protecting the north- eastern dominions of Spain in America and giving safety to the homeward-bound Spanish plate fleet sailing the Gulf Stream route. CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS is an ancient builders. The fort contains guardrooms, fortification dating from the Spanish Co- dungeons, living quarters for the garrison, lonial period in America. It represents storerooms, and a chapel. Nearly all the part of Spain's contribution to life in the rooms open on a court, about 100 feet New World, and'is symbolic of the explorer square. and pioneetspirit-the will to build from Although the castillo was the most im- the wilderness a newcenter of civilization portant fortification in colonial Florida, it and a hav@l1"it£gi't'i'iisdatnger. In this his- was by no means the only defense. Earth- toric structure, the Spanish people have works and palisades extended from the left us a heritage that is an important cul- castle to enclose the little town of St. tural connection with the Latin-American Augustine, an area of less than a square nations to .the south, as well as another mile. Far to the south, west, and north means of understanding the diverse old were military outposts. Sixteen miles to the ways that have contributed to the making south was the strongest of these, the stone of modern America. -

Corleone, a Tale of Sicily. By: F. Marion Crawford. / Novel (Paperback)

UDZHBQEHQAT5 eBook \ Corleone, a Tale of Sicily. by: F. Marion Crawford. / Novel (Paperback) Corleone, a Tale of Sicily. by: F. Marion Crawford. / Novel (Paperback) Filesize: 1.47 MB Reviews Absolutely essential go through book. It is actually loaded with knowledge and wisdom You can expect to like the way the blogger compose this pdf. (Pascale Bernhard) DISCLAIMER | DMCA TXV8KERYXWPX > Kindle / Corleone, a Tale of Sicily. by: F. Marion Crawford. / Novel (Paperback) CORLEONE, A TALE OF SICILY. BY: F. MARION CRAWFORD. / NOVEL (PAPERBACK) To download Corleone, a Tale of Sicily. by: F. Marion Crawford. / Novel (Paperback) PDF, remember to refer to the link beneath and download the ebook or gain access to other information that are in conjuction with CORLEONE, A TALE OF SICILY. BY: F. MARION CRAWFORD. / NOVEL (PAPERBACK) ebook. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. Francis Marion Crawford (August 2, 1854 - April 9, 1909) was an American writer noted for his many novels, especially those set in Italy, and for his classic weird and fantastic stories.Crawford was born in Bagni di Lucca, Italy, the only son of the American sculptor Thomas Crawford and Louisa Cutler Ward, the brother of writer Mary Crawford Fraser (aka Mrs. Hugh Fraser), and the nephew of Julia Ward Howe, the American poet. He studied successively at St Paul s School, Concord, New Hampshire; Cambridge University; University of Heidelberg; and the University of Rome. In 1879 he went to India, where he studied Sanskrit and edited in Allahabad The Indian Herald. Returning to America in February 1881, he continued to study Sanskrit at Harvard University for a year and for two years contributed to various periodicals, mainly The Critic. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Academy of Music, 47, 48 appearance of, 29, 68, 215 afternoon tea, 342, 343 background and personal traits of, 4–5, Age of Innocence, The (Wharton), 95, 26–29, 31 140, 275 Bohemian party of, 400 Allard, Jules, 132, 158, 173, 260–261, 304, children of, 30, 99–104 306, 307–308, 323, 327, 329, 331 daughters’ marriages and, 75–78, Alva (yacht), 234–235, 236, 312 121–122, 170, 280 Ambassadress (yacht), 27, 30, 234 denunciation of vulgar displays by, Anthony, Susan B., 442 402, 425 archery, 74, 273, 334 diamond jewelry of, 61, 103, 227–229, aristocracy, 7, 36, 112–113, 118–119, 122– 369, 374, 425 123, 222, 224, 225, 378, 380–382, 443 dinner parties and, 350, 351, 354 marriages to, 382–390 European travel of, 377, 380 arrivistes. See nouveau riches four hundred and, 38, 47, 183 art collections, 10, 12, 26, 35, 37, 132, 133, houses of, 103, 135, 138, 157, 165–177, 257–258, 379 189, 368, 426, 427, 441, 450 Belmont, 95, 139 husband’s death and, 76, 77, 78, 170 Huntington, 181 last years and death of, 425–427, 453 as masculine pursuit, 88–91 Lehr and, 107, 109, 111 philanthropic donations of, 454 marriage of, 29, 30, 31, 234, 269 prevailing taste in, 88–89 McAllister and, 33–38, 52, 61, 104, 105, Stewart, 137–138 166, 300 Vanderbilt, 149–150, 288, 295 morning routine of, 68, 69–70 Whitney, 188, 189 as national legend, 177 Astor, Alice, 101, 427, 441, 442 Newport and, 157, 169, 171, Astor, Ava WillingCOPYRIGHTED (Mrs. -

O. Henry's Influences and Working Methods

THE CREATION OF THE FOUR MILLION: O. HENRY’S INFLUENCES AND WORKING METHODS ____ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri _____________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _______________________________ by GARY KASS Dr. Tom Quirk, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 © Copyright by Gary Kass 2008 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE CREATION OF THE FOUR MILLION: O. HENRY’S INFLUENCES AND WORKING METHODS Presented by Gary Kass A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________________ Professor Tom Quirk ________________________________________ Professor John Evelev ________________________________________ Professor Steve Weinberg ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Helen Snow, North Carolina Librarian of the Greensboro Public Library, who mailed me a copy of the notes taken by C. Alphonso Smith, O. Henry’s first biographer, when he interviewed Anne Partlan in New York on February 11, 1916. Thanks also to the librarians who helped me locate material from vol. 2 of Success magazine. Those issues, dating from December 1898 through November 1899, are missing from the microfilm record, having apparently never been photographed. I am grateful to Ann Dodge, coordinator of reader services in the Special Collections Department of John Hay Library at Brown University, who located the original issues on her shelves, and to Kathleen Brooks, library technical assistant, who kindly paged through each issue in search of Partlan material. In the process, she discovered “One Woman’s Hard Road to Fortune,” a profile of Partlan which I had not seen cited anywhere and which I was unaware of. -

Names and Addresses of Living Bachelors and Masters of Arts, And

id 3/3? A3 ^^m •% HARVARD UNIVERSITY. A LIST OF THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF LIVING ALUMNI HAKVAKD COLLEGE. 1890, Prepared by the Secretary of the University from material furnished by the class secretaries, the Editor of the Quinquennial Catalogue, the Librarian of the Law School, and numerous individual graduates. (SKCOND YEAR.) Cambridge, Mass., March 15. 1890. V& ALUMNI OF HARVARD COLLEGE. \f *** Where no StateStat is named, the residence is in Mass. Class Secretaries are indicated by a 1817. Hon. George Bancroft, Washington, D. C. ISIS. Rev. F. A. Farley, 130 Pacific, Brooklyn, N. Y. 1819. George Salmon Bourne. Thomas L. Caldwell. George Henry Snelling, 42 Court, Boston. 18SO, Rev. William H. Furness, 1426 Pine, Philadelphia, Pa. 1831. Hon. Edward G. Loring, 1512 K, Washington, D. C. Rev. William Withington, 1331 11th, Washington, D. C. 18SS. Samuel Ward Chandler, 1511 Girard Ave., Philadelphia, Pa. 1823. George Peabody, Salem. William G. Prince, Dedham. 18S4. Rev. Artemas Bowers Muzzey, Cambridge. George Wheatland, Salem. 18S5. Francis O. Dorr, 21 Watkyn's Block, Troy, N. Y. Rev. F. H. Hedge, North Ave., Cambridge. 18S6. Julian Abbott, 87 Central, Lowell. Dr. Henry Dyer, 37 Fifth Ave., New York, N. Y. Rev. A. P. Peabody, Cambridge. Dr. W. L. Russell, Barre. 18S7. lyEpes S. Dixwell, 58 Garden, Cambridge. William P. Perkins, Wa}dand. George H. Whitman, Billerica. Rev. Horatio Wood, 124 Liberty, Lowell. 1828] 1838. Rev. Charles Babbidge, Pepperell. Arthur H. H. Bernard. Fredericksburg, Va. §3PDr. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 113 Boylston, Boston. Rev. Joseph W. Cross, West Boylston. Patrick Grant, 3D Court, Boston. Oliver Prescott, New Bedford. -

Award Winners (Information and Photos Published in Powerships Issue #275 and #276 and Steamboat Bill Issue #245)

Created and Compiled by: Jillian Fulda The Dibner Intern 2010 Award Winners (Information and photos published in PowerShips issue #275 and #276 and Steamboat Bill issue #245) C. Bradford Mitchell Award-2010 This award was given to Christopher Winters in recognition of his publication Centennial: Steaming Through the American Century. This full color book documents and chronicles the history of the freighter St. Mary’s Challenger. In April 2006, St. Mary’s Challenger became the first Great Lakes ship to reach 100 years of age and still in operational service. Mr. Winters, a marine photographer, spent five seasons capturing this vessel for the SSHSA photo. book. Thanks to him, the future of maritime history will always have a record of this historic vessel. H. Graham Wood Award-2010 This award was given to Francis J. Duffy in recognition of his contributions and work with SSHSA, with strong emphasis on recording and preserving the legacy of ships, New York shipping and the United States Merchant Marine. Mr. Duffy, who grew up in New York, is a professional writer and photographer specializing in the maritime industry. He was a special correspondent for the publication The National Fisherman and from 1984 to 1993 he served as director of public relations for Moran Towing & Transportation Company, where he was also editor of Moran’s Tow Line magazine. Mr. Duffy is also a principal in Granard Associates, a firm serving the maritime industry. With William H. Miller, Mr. Duffy co- authored The New York Harbor Book. Various articles and photographs by him have appeared in The New York Times, Journal of Commerce, Photo published in Steamboat Bill issue Long Island Newsday, Cruise Travel, U.S.