The Limits of Auteurism: Case Studies in the Critically Constructed New Hollywood, by Nicholas Godfrey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Analysis Easy Rider - Focus on American Dream, Hippie Life Style and Soundtrack

Film Analysis Easy Rider - Focus on American Dream, Hippie Life Style and Soundtrack - Universität Augsburg Philologisch-Historische Fakultät Lehrstuhl für Amerikanistik PS: The 60s in Retrospect – A Magical History Tour Dozent: Udo Legner Sommersemester 2013 Referenten: Lisa Öxler, Marietta Braun, Tobias Berber Datum: 10.06.2013 Easy Rider – General Information ● Is a 1969 American road movie ● Written by Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Terry Southern ● Produced by Fonda and directed by Hopper ● Tells the story of two bikers (played by Fonda and Hopper) who travel through the American Southwest and South Easy Rider – General Information ● Success of Easy Rider helped spark the New Hollywood phase of filmmaking during the early 1970s ● Film was added to the Library of Congress National Registry in 1998 ● A landmark counterculture film, and a ”touchstone for a generation“ that ”captured the national imagination“ Easy Rider – General Information ● Easy Rider explores the societal landscape, issues, and tensions in the United States during the 1960s, such as the rise and fall of the hippie movement, drug use, and communal lifestyle ● Easy Rider is famous for its use of real drugs in its portrayal of marijuana and other substances Easy Rider - Plot ● Protagonists are two hippies in the USA of the 1970s: – Wyatt (Fonda), nicknamed "Captain America" dressed in American flag- adorned leather – Billy (Hopper) dressed in Native American-style buckskin pants and shirts and a bushman hat Easy Rider - Plot ● Character's names refer to Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid ● The former is appreciative of help and of others, while the latter is often hostile and leery of outsiders. -

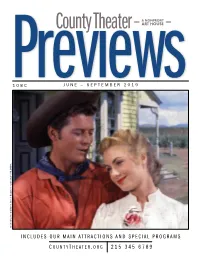

County Theater ART HOUSE

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

Noviembre 2010

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 913691125 (taquilla) Fax: 91 4672611 913692118 [email protected] (gerencia) http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html Fax: 91 3691250 NIPO (publicación electrónica) :554-10-002-X MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala noviembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2010 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 16.15 - 00.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.00 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico NOVIEMBRE 2010 Don Siegel (y II) III Muestra de cine coreano (y II) VIII Mostra portuguesa Cine y deporte (III) I Ciclo de cine y archivos Muestra de cine palestino de Madrid Premios Goya (II) Buzón de sugerencias: Hayao Miyazaki Cine para todos Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. -

Arbeitsergebnisse Eines Englisch-Leistungskurses Des

Arbeitsergebnisse eines Englisch‐Leistungskurses des Albrecht‐Dürer‐Gymnasiums im Rahmen der Teilnahme am Berlinale Schulprojekt 2010 zum Film Road, Movie von Dev Bengal Berlin, 22.03.2010 Inhaltsübersicht S. 2 1 . Vorbereitung, Durchführung und Auswertung des Projekts S. 3 ‐ 4 2. The Role of Religion in “Road, Movie” S. 5 ‐ 8 3. Social Order and the Caste System in India and “Road, Movie” S. 8 ‐ 11 4. Water Issues in India and in “Road, Movie” S. 11 ‐ 12 5. The Representation of Masculinity in” Road, Movie” S. 12 ‐ 14 6. Fairy Tale Elements in “Road, Movie” S. 14 ‐ 15 7. The Truck as a `character´ in “Road, Movie” S. 16 ‐ 17 8. Films in Films, as shown in “Road, Movie” S. 17 ‐ 18 9. Quellen S. 18 ‐ 19 1. Vorbereitung, Durchführung und Auswertung des Projekts Die Teilnahme des Englisch‐Leistungskurses erfolgte im Rahmen des 4. Kurssemesters zum Thema „Herausforderungen der Gegenwart“ mit dem Unterthema „Urban, Suburban and Rural Lifestyles.“ Im vorhergehenden Unterricht hatten sich die Schüler mit Fragen der Besiedlungsgeschichte der USA, der Raumerschließung und der Raumüberwindung auf dem nordamerikanischen Kontinent und der u.a. daraus abzuleitenden typischen Siedlungs‐ und Mobilitätsmuster beschäftigt. Unter anderem wurden in Kurzreferaten amerikanische Road Movies vorgestellt und auf ihre kulturellen Implikationen hin gedeutet (Freiheitsdrang, Initiation, Suche nach Identität etc.). Die Möglichkeit einer Vertiefung dieser Thematik am Beispiel des indischen Films Road, Movie traf auf großes Interesse der Schülerinnen und Schüler, wobei insbesondere von Bedeutung war, dass es sich bei Road, Movie nicht um einen Bollywood Film handelt, sondern um eine kleinere Produktion. Der Kinobesuch der Schülerinnen und Schüler erfolgte im Rahmen der Berlinale am 12.02. -

Ross Lipman Urban Ruins, Found Moments

Ross Lipman Urban Ruins, Found Moments Los Angeles premieres Tues Mar 30 | 8:30 pm $9 [students $7, CalArts $5] Jack H. Skirball Series Known as one of the world’s leading restorationists of experimental and independent cinema, Ross Lipman is also an accomplished filmmaker, writer and performer whose oeuvre has taken on urban decay as a marker of modern consciousness. He visits REDCAT with a program of his own lyrical and speculative works, including the films 10-17-88 (1989, 11 min.) and Rhythm 06 (1994/2008, 9 min.), selections from the video cycle The Perfect Heart of Flux, and the performance essay The Cropping of the Spectacle. “Everything that’s built crumbles in time: buildings, cultures, fortunes, and lives,” says Lipman. “The detritus of civilization tells us no less about our current epoch than an archeological dig speaks to history. The urban ruin is particularly compelling because it speaks of the recent past, and reminds us that our own lives and creations will also soon pass into dust. These film, video, and performance works explore decay in a myriad of forms—architectural, cultural, and personal.” In person: Ross Lipman “Lipman’s films are wonderful…. strong and delicate at the same time… unique. The rhythm and colors are so subtle, deep and soft.” – Nicole Brenez, Cinémathèque Française Program Self-Portrait in Mausoleum DigiBeta, 1 min., 2009 (Los Angeles) Refractions and reflections shot in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery: the half-life of death’s advance. Stained glass invokes the sublime in its filtering of light energy, a pre-cinematic cipher announcing a crack between worlds. -

Every Good Boy Deserves Fun: One Dog's Journey to the North

Every Good Boy Deserves Fun: One Dog’s Journey to the North “North...of all geographical terms it is the most personal, the most emotional, the most elusive. And perhaps the one which evokes the most powerful feelings” (Davidson, 2009) Davidson’s description of the powerful symbolism of the North as a destination, as a dream, echoes the romantic hyperbole of the early polar explorers searching for the last untamed wilderness in an increasingly industrial world; “the great adventure of the ice, deep and pure as infinity...nature itself in its profundity” (Nansen,1894). It establishes North as the direction of adventures. This chapter will examine The North as the site of mystery and adventure… one of the last wildernesses to explore but one which is paradoxically comfortable; populated only sparsely by oddly familiar characters. Through the examination of the author’s own short animation North, it will look at the use of narrative devices and media references to reflect on the symbolism of the North –and investigate the British relationship with it; not with the media construct of The North-South divide but rather with a broader, more complex idea of a conceptual, an imagined North-ness. This is seen in relation to certain stereotypes of iconic Britishness – our relationship with the sea, and its poetic evocation through the shipping forecast, with our dogs... and with our TV-facing sofas. Drawing on its author’s own travel experiences, and field research in Norway and Iceland, the short animation North can be viewed as a Road Movie, a Hero’s Journey, with Colin the dog as unlikely hero. -

Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2004 Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Custom Citation King, Homay. "Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces." Camera Obscura 19, no. 2/56 (2004): 105-139, doi: 10.1215/02705346-19-2_56-105. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/40 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Homay King, “Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces,” Camera Obscura 56, v. 19, n. 2 (Summer 2004): 104-135. Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces Homay King How to make the affect echo? — Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes1 1. In the Middle of Things: Opening Night John Cassavetes’ Opening Night (1977) begins not with the curtain going up, but backstage. In the first image we see, Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands) has just exited stage left into the wings during a performance of the play The Second Woman. In this play, Myrtle acts the starring role of Virginia, a woman in her early sixties who is trapped in a stagnant second marriage to a photographer. Both Myrtle and Virginia are grappling with age and attempting to come to terms with the choices they have made throughout their lives. -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue Formatted

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue with Molly Haskell, 1997 Bruce Jenkins: Let me say that these dialogues have for the better part of this decade focused on that part of cinema devoted to narrative or dramatic filmmaking, and we've had evenings with actors, directors, cinematographers, and I would say really especially with those performers that we identify with the cutting edge of narrative filmmaking. In describing tonight's guest, Molly Haskell spoke of a creative artist who not only did a sizeable number of important projects but more importantly, did the projects that she herself wanted to see made. The same I think can be said about Molly Haskell. She began in the 1960s working in New York for the French Film Office at that point where the French New Wave needed a promoter and a writer and a translator. She eventually wrote the landmark book From Reverence to Rape on women in cinema from 1973 and republished in 1987, and did sizable stints as the film reviewer for Vogue magazine, The Village Voice, New York magazine, New York Observer, and more recently, for On the Issues. Her most recent book, Holding My Own in No Man's Land, contains her last two decades' worth of writing. I'm please to say it's in the Walker bookstore, as well. Our other guest tonight needs no introduction here in the Twin Cities nor in Cloquet, Minnesota, nor would I say anyplace in the world that motion pictures are watched and cherished. She's an internationally recognized star, but she's really a unique star. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 Paul L. Robertson Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Appalachian Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons © Paul L. Robertson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5854 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robertson i © Paul L. Robertson 2019 All Rights Reserved. Robertson ii The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Paul Lester Robertson Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2000 Master of Arts in Appalachian Studies, Appalachian State University, 2004 Master of Arts in English, Appalachian State University, 2010 Director: David Golumbia Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2019 Robertson iii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank his loving wife A. Simms Toomey for her unwavering support, patience, and wisdom throughout this process. I would also like to thank the members of my committee: Dr. David Golumbia, Dr. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author