Commodore Moore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Commodore Rob Woods OBE Chief of Staff (Air), Defence Equipment & Support Royal Air Force the Team…

A Warfighters View: Weapon System Availability – A Collaborative Challenge Air Commodore Rob Woods OBE Chief of Staff (Air), Defence Equipment & Support Royal Air Force The Team….. Air Cdre Rob Woods Mr Richard Hamilton MoD DE&S BAE Systems plc Gp Capt Simon Vicary Mr Geraint Spearing MoD DE&S MoD DECA Mr Ian Manley Mr Ian Cole MoD DE&S MoD DECA UK Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S) “To equip and support our Armed Forces for operations now and in the future” DE&S’s Role • Procure & support equipment, through life, for UK’s Armed Forces for both current & future operations • MOD’s lead department for commercial activities • Manage relationships with MOD, the Front Line & Industry DE&S HQ, MOD Abbey Wood, Bristol, UK DE&S Budget to Spend 2019/20 • £10.8 Billion Core Spend: − £5.4 Billion for Purchase of New Equipment − £5.4 Billion for Equipment Support • £3.9 Billion budget for Air Domain, 56% of which for Support Air Domain Portfolio Backdrop for Transformation in Support: 2000-05 • Strategic Defence Review 1998 • Similar lessons learnt over multiple –Smart Acquisition operations; urgent need to improve • DLO Strategy • Increasing demand for UK military –20% Savings & ‘Transformation capability across the globe Staircase’ • Nature of operations changed • Air & Land End-to-End Review • Defence White Paper 2004 • Need to find efficiencies • Government Efficiency Review 2004 – Preserve current & future capability • Formation of DE&S End-2-End Review of Air & Land Logistics - 2003 • Simplified lines & levels of support - From 4 x Lines of -

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

Information Regarding Who Has Succeeded Air Commodore N T

Air Command Secretariat i Spitfire Block Headquarters Air Command Royal Air Force High Wycombe Buckinghamshire HP14 4UE Ref: FOI 2020/00701 10 February 2020 Dear Thank you for your email of 17 January 2020 requesting the following information: “1) Who has succeeded Air Commodore N T Bradshaw as Assistant Chief of Staff Media & Communications in November 2019? With regards to today's London Gazette https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/62888/data.pdf, 2) Is the appointment of Assistant Chief of Air Staff Plans a new appointment? 3) What are the responsibilities of this appointment? 4) Who has replaced AVM L S Taylor as Head Rapid Capabilities Office?” I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA). A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that information in scope of your request is held. 1) The process for recruiting the replacement for Air Commodore N T Bradshaw is currently ongoing. Under Section 16 (Advice and Assistance) you may find it useful to know that this post has now been civilianised. 2) Please note that Section 1 of the FOIA gives an applicant the right to access recorded information held by public authorities at the time that the request was made. It does not require public authorities to answer questions, provide explanations nor give opinions unless they are held on record. However, under Section 16 (Advice and Assistance) I can inform you that the Assistant Chief of Air Staff Plans is a new position. -

Commander Commodore José António Mirones Spanish Navy Commander of Standing Nato Maritime Group Two (Snmg1)

COMMANDER COMMODORE JOSÉ ANTÓNIO MIRONES SPANISH NAVY COMMANDER OF STANDING NATO MARITIME GROUP TWO (SNMG1) José António Mirones was born in 1965 and joined the Portuguese Navy Naval Academy in 1983, graduating with the class of 88. After Fleet training, including involvement in disaster relief in the North Sea, in the aftermath of Piper Alfa oil rig disaster, and exchange with the United States Navy, in USS Joseph Hewes, his early years were spent at sea as a bridge watch-keeper, carrying out fishery protection and maritime securityoperations. Principal Warfare Officer in several frigates, was also Head of Department (Operations) and Executive officer with operational deployments to the Adriatic, supporting EU and NATO embargo operations; Mediterranean, namely Operation Enduring Freedom, in the wake of September 11th; Baltic; Artic Ocean and wider Atlantic. He completed the specialist ASW´s course in 1999. Took command of the frigate Bartolomeu Dias, in January 2009, as her first Commanding Officer. Promoted to Captain, acted as CTG (EUROMARFOR TG) for two occasions and, more recently, as Commodore, was the force commander for the EU naval operation ATALANTA, in the Indian Ocean. His staff appointments have included two tours at the Naval Staff (Plans and Policy and External Affairs Division). His last shore assignment was as Military Assistant to the Chief of the Defence Staff. José António Mirones personal decorations include the Distinguished Service Medal, Meritorious Service Medal, Navy Cross as well as various campaign ribbons and foreign medals. @NATOMaritimeCommand @NATO_MARCOM @NATO HQ MARCOM Allied Maritime Command I Public Affairs OfficeI [email protected] I www.mc.nato.int. -

Air Chief Marshal Frank Robert MILLER, CC, CBE, CD Air Member

Air Chief Marshal Frank Robert MILLER, CC, CBE, CD Air Member Operations and Training (C139) Chief of the RCAF Post War Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff and First Chief of Staff 01 August 1964 - 14 July 1966 Born: 30 April 1908 Kamloops, British Columbia Married: 03 May 1938 Dorothy Virginia Minor in Galveston, Texas Died: 20 October 1997 Charlottesville, Virginia, USA (Age 89) Honours CF 23/12/1972 CC Companion of the Order of Canada Air Chief Marshal RCAF CG 13/06/1946 CBE Commander of the Order of the British Empire Air Vice-Marshal RCAF LG 14/06/1945+ OBE Officer of the Order of the British Empire Air Commodore RCAF LG 01/01/1945+ MID Mentioned in Despatches Air Commodore RCAF Education 1931 BSc University of Alberta (BSc in Civil Engineering) Military 01/10/1927 Officer Cadet Canadian Officer Training Corps (COTC) 15/09/1931 Pilot Officer Royal Canadian Air Force 15/10/1931 Pilot Officer Pilot Training at Camp Borden 16/12/1931 Flying Officer Receives his Wings 1932 Flying Officer Leaves RCAF due to budget cuts 07/1932 Flying Officer Returns to the RCAF 01/02/1933 Flying Officer Army Cooperation Course at Camp Borden in Avro 621 Tutor 31/05/1933 Flying Officer Completes Army Cooperation Course at Camp Borden 30/06/1933 Flying Officer Completes Instrument Flying Training on Gipsy Moth & Tiger Moth 01/07/1933 Flying Officer Seaplane Conversion Course at RCAF Rockcliffe Vickers Vedette 01/08/1933 Flying Officer Squadron Armament Officer’s Course at Camp Borden 22/12/1933 Flying Officer Completes above course – Flying the Fairchild 71 Courier & Siskin 01/01/1934 Flying Officer No. -

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter, USN: Midshipman David Glasgow Farragut Part One of a Three-Part Series

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter, USN: Midshipman David Glasgow Farragut Part One of a three-part series Vice Admiral Jim Sagerholm, USN (Ret.), September 15, 2020 blueandgrayeducation.org David Glasgow Farragut | National Portrait Gallery In any discussion of naval leadership in the Civil War, two names dominate: David Glasgow Farragut and David Dixon Porter. Both were sons of David Porter, one of the U.S. Navy heroes in the War of 1812, Farragut having been adopted by Porter in 1808. Farragut’s father, George Farragut, a seasoned mariner from Spain, together with his Irish wife, Elizabeth, operated a ferry on the Holston River in eastern Tennessee. David Farragut was their second child, born in 1801. Two more children later, George moved the family to New Orleans where the Creole culture much better suited his Mediterranean temperament. Through the influence of his friend, Congressman William Claiborne, George Farragut was appointed a sailing master in the U.S. Navy, with orders to the naval station in New Orleans, effective March 2, 1807. George Farragut | National Museum of American David Porter | U.S. Naval Academy Museum History The elder Farragut traveled to New Orleans by horseback, but his wife and four children had to go by flatboat with the family belongings, a long and tortuous trip lasting several months. A year later, Mrs. Farragut died from yellow fever, leaving George with five young children to care for. The newly arrived station commanding officer, Commander David Porter, out of sympathy for Farragut, offered to adopt one of the children. The elder Farragut looked to the children to decide which would leave, and seven-year-old David, impressed by Porter’s uniform, volunteered to go. -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

Revised Tri Ser Pen Code 11 12 for Printing

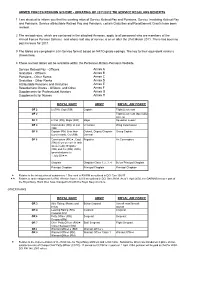

ARMED FORCES PENSION SCHEME - UPRATING OF 2011/2012 TRI SERVICE REGULARS BENEFITS 1 I am directed to inform you that the existing rates of Service Retired Pay and Pensions, Service Invaliding Retired Pay and Pensions, Service attributable Retired Pay and Pensions, certain Gratuities and Resettlement Grants have been revised. 2 The revised rates, which are contained in the attached Annexes, apply to all personnel who are members of the Armed Forces Pension Scheme and whose last day of service is on or after the 31st March 2011. There has been no pay increase for 2011. 3 The tables are compiled in a tri-Service format based on NATO grade codings. The key to their equivalent ranks is shown here. 4 These revised tables will be available within the Personnel-Miltary-Pensions Website. Service Retired Pay - Officers Annex A Gratuities - Officers Annex B Pensions - Other Ranks Annex C Gratuities - Other Ranks Annex D Attributable Pensions and Gratuities Annex E Resettlement Grants - Officers, and Other Annex F Supplements for Professional Aviators Annex G Supplements for Nurses Annex H ROYAL NAVY ARMY ROYAL AIR FORCE OF 2 Lt (RN), Capt (RM) Captain Flight Lieutenant OF 2 Flight Lieutenant (Specialist Aircrew) OF 3 Lt Cdr (RN), Major (RM) Major Squadron Leader OF 4 Commander (RN), Lt Col Lt Colonel Wing Commander (RM), OF 5 Captain (RN) (less than Colonel, Deputy Chaplain Group Captain 6 yrs in rank), Col (RM) General OF 6 Commodore (RN)«, Capt Brigadier Air Commodore (RN) (6 yrs or more in rank (preserved)); Brigadier (RM) and Col (RM) (OF6) (promoted prior to 1 July 00)«« Chaplain Chaplain Class 1, 2, 3, 4 Below Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain « Relates to the introduction of substantive 1 Star rank in RN/RM as outlined in DCI Gen 136/97 «« Relates to rank realignment for RM, effective from 1 Jul 00 as outlined in DCI Gen 39/99. -

US Military Ranks and Units

US Military Ranks and Units Modern US Military Ranks The table shows current ranks in the US military service branches, but they can serve as a fair guide throughout the twentieth century. Ranks in foreign military services may vary significantly, even when the same names are used. Many European countries use the rank Field Marshal, for example, which is not used in the United States. Pay Army Air Force Marines Navy and Coast Guard Scale Commissioned Officers General of the ** General of the Air Force Fleet Admiral Army Chief of Naval Operations Army Chief of Commandant of the Air Force Chief of Staff Staff Marine Corps O-10 Commandant of the Coast General Guard General General Admiral O-9 Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Rear Admiral O-8 Major General Major General Major General (Upper Half) Rear Admiral O-7 Brigadier General Brigadier General Brigadier General (Commodore) O-6 Colonel Colonel Colonel Captain O-5 Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Commander O-4 Major Major Major Lieutenant Commander O-3 Captain Captain Captain Lieutenant O-2 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant Lieutenant, Junior Grade O-1 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant Ensign Warrant Officers Master Warrant W-5 Chief Warrant Officer 5 Master Warrant Officer Officer 5 W-4 Warrant Officer 4 Chief Warrant Officer 4 Warrant Officer 4 W-3 Warrant Officer 3 Chief Warrant Officer 3 Warrant Officer 3 W-2 Warrant Officer 2 Chief Warrant Officer 2 Warrant Officer 2 W-1 Warrant Officer 1 Warrant Officer Warrant Officer 1 Blank indicates there is no rank at that pay grade. -

Charles Henry Davis. Is 07-18 77

MEMO I R CHARLES HENRY DAVIS. IS 07-18 77. C. H. DAVIS. RKAD ISEFORE rirrc NATFONAF, ACADK.MY, Ai'itn,, 1S()(>. -1 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF CHARLES HENRY DAVIS. CHARLES HENRY DAVIS was born in Boston, January 10, 1807. He was the youngest son of Daniel Davis, Solicitor General of the State of Massachusetts. Of the other sons, only one reached maturity, Frederick Hersey Davis, who died in Louisiana about 1840, without issue. The oldest daughter, Louisa, married William Minot, of Boston. Daniel Davis was the youngest son of Hon. Daniel Davis, of Barnstablc, justice of the Crown and judge of probate and com- mon pleas for the county of Barn.stable. The family had been settled in Barnstable since 1038. Daniel Davis, the second, studied law, settled first in Portland (then Fahnouth), in the province of Maine, and moved to Boston in 1805. He married Lois Freeman, daughter of Captain Constant Freeman, also of Cape Cod. Her brother. Iiev. James Freeman, was for forty years rector of the King's Chapel in Boston, and was the first Unita- rian minister in Massachusetts. The ritual of King's Chapel was changed to conform to the modified views of the rector, and remains the same to this day. Another brother, Colonel Constant Freeman, served through the Revolutionary war and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel of artillery. In 1802 lie was on the permanent establishment as lieutenant colonel of the First United States Artillery. After the war of 1812-'14 be resigned and was Fourth Auditor of tlie Treasury until bis death, in 1824. -

Equivalent Ranks of the British Services and U.S. Air Force

EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Commissioned Ranks Marshal of the Admiral of the Fleet Field Marshal Royal Air Force Command General of the Air Force Admiral Air Chief Marshal General General Vice Admiral Air Marshal Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Rear Admiral Air Vice Marshal Major General Major General Commodore Brigadier Air Commodore Brigadier General Colonel Captain Colonel Group Captain Commander Lieutenant Colonel Wing Commander Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Squadron Leader Commander Major Major Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Captain EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT First Lieutenant Sub Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Second Lieutenant Midshipman Second Lieutenant Pilot Officer Notes: 1. Five-Star Ranks have been phased out in the British Services. The Five-Star ranks in the U.S. Services are reserved for wartime only. 2. The rank of Midshipman in the Royal Navy is junior to the equivalent Army and RAF ranks. EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Non-commissioned Ranks Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Class 1 (RSM) Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Warrant Officer Class 2b (RQSM) Chief Command Master Sergeant Warrant Officer Class 2a Chief Master Sergeant Chief Petty Officer Staff Sergeant Flight Sergeant First Senior Master Sergeant Chief Technician Senior Master Sergeant Petty Officer Sergeant Sergeant First Master Sergeant EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. -

Commodore Tom Guy Royal Navy Deputy Director

Biography Combined Joint Operations from the Sea Centre of Excellence Commodore Tom Guy Royal Navy Deputy Director Tom Guy is fortunate to have enjoyed a broad range of rewarding operational, staff and command roles ashore and afloat from the UK to the Far East. Early appointments included a wide variety of ships, from patrol craft to mine-hunters, frigates, destroyers and aircraft carriers, ranging from fishery protection to counter-piracy and UN embargo operations as well as training and operating with a broad range of NATO allies. Having trained as a navigator and diving officer early on, Tom specialised as an anti-submarine warfare officer and then a Group Warfare Officer. He then went on to command HMS Shoreham, a new minehunter out of build, and then HMS Northumberland, fresh out of refit as one of the most advanced anti-submarine warfare frigates in the world. His time as Chief of Staff to the UK’s Commander Amphibious Task Group included the formation of the Response Force Task Group and its deployment on Op ELLAMY (Libya) in 2011 and he later had the great privilege of serving as the Captain Surface Ships (Devonport Flotilla). Shore appointments have included the Strategy area in the MOD, a secondment to the Cabinet Office, Director of the Royal Naval Division of the Joint Services Command and Staff College, and the role of DACOS Force Generation in Navy Command Headquarters. He has held several Operational Staff appointments, including service in the Headquarters of the Multi National Force Iraq (Baghdad) in 2005. Other operational tours have included the Balkans and the Gulf, both ashore and afloat.