Outline for Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cerflfrcacrór*6Reps 0F L+'- Be 0 0 L.Tar 2018

REPUBLICA DE COLOMBIA flro(xtPoRu usrro PAfS @ utrurrurenron MINISTERIO DEL INTERIOR cERflFrcAcrór*6rEps 0f l+'- be 0 0 l.tAR 2018 "Sobre la presencia o no de comunidades étn¡cas en las zonas de proyectos, obras o actividades a realizarse"- EL DIRECTOR DE CONSULTA PREVIA En ejercicio de las facultades legales y reglamentarias en especial, las confer¡das en el artículo '16 del numeral 5 del Decreto 2893 de 2011 y la Resolución 0755 del 15 de mayo de 2017 , y Acta de Posesión del 16 de mayo de 2017 y, CONSIDERANDO: Que se recibió en el Ministerio del lntenor el dia 1 5 de enero de 2018, el oficio con radicado externo EXTMllS-995, por medio del cual el señor HECTOR FABIO ARISTIáBAL RODROGUEz, identificado con cedula de ciudadanía No. 16.741.251, en calidad de Director Técn¡co Ambiental (C), de la Corporación Autónoma Reg¡onal del Valle del Cauca -CVC, identificado con NIT No. 890399002-7 solicita se expida certificación de presencia o no de comun¡dades étnicas en el área del proyecto: "FORMULACIÓÍ,J OEL PLAN DE MANEJO AMBIENTAL DE ACUíFERO PARA EL SISTEMA ACUíFERO DEL VALLE DEL sAM 3.1.", localizado en jurisdicción de los Municipios de JamundÍ, Candelaria,'AIJCA Sant¡ago de Cali, Pradera, Florida, Palmira, Yumbo, El Gerrito, Vijes, Ginebra, Guacarí, Yotoco, Buga, San Pedro, Tuluá, Riofrio, Andalucía, Trujillo, Bugalagrande, Zarzal, Roldanillo, La Victor¡a, La Unión, Toro, Obando, Cartago, Ansermanuevo, en el Departamento del Valle del Cauca, identificado con las s¡gu¡entes coordenadas: Fuente: Suministrada por el sol¡c¡tante; rad¡c¿do externo EXTMll S'995 del 15 de enero de 2018. -

Formato Ejemplo3.13 Memo De Planeacion

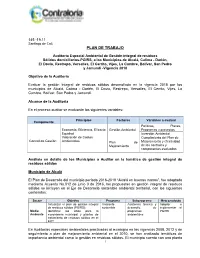

145 -19.11 Santiago de Cali, PLAN DE TRABAJO Auditoria Especial Ambiental de Gestión integral de residuos Sólidos domiciliarios-PGIRS, a los Municipios de Alcalá, Calima - Darién, El Dovio, Restrepo, Versalles, El Cerrito, Vijes, La Cumbre, Bolívar, San Pedro y Jamundí -Vigencia 2018 Objetivo de la Auditoría Evaluar la gestión integral de residuos sólidos desarrollada en la vigencia 2018 por los municipios de Alcalá, Calima - Darién, El Dovio, Restrepo, Versalles, El Cerrito, Vijes, La Cumbre, Bolívar, San Pedro y Jamundí. Alcance de la Auditoría En el proceso auditor se evaluarán las siguientes variables: Principios Factores Variables a evaluar Componente Políticas, Planes, Economía, Eficiencia, Eficacia Gestión Ambiental Programas y proyectos Equidad Inversión Ambiental Valoración de Costos Cumplimiento del Plan de Control de Gestión Ambientales Plan de Mejoramiento y efectividad Mejoramiento de los controles y componentes evaluados Análisis en detalle de los Municipios a Auditar en la temática de gestión integral de residuos sólidos Municipio de Alcalá El Plan de Desarrollo del municipio período 2016-2019 “Alcalá en buenas manos”, fue adoptado mediante Acuerdo No.012 de junio 3 de 2016, las propuestas en gestión integral de residuos sólidos se incluyen en el Eje de Desarrollo sostenible ambiental territorial, con los siguientes contenidos: Sector Objetivo Programa Subprograma Meta producto Actualizar el plan de gestión integral Ambiente Asistencia técnica y Adoptar e de residuos sólidos (PGIRS); sostenible desarrollo de implementar el Medio Identificar los sitios para la programas PGIRS Ambiente escombrera municipal y plantas de ambientales tratamiento de residuos sólidos en el EOT En Auditorías especiales ambientales practicadas al municipio en las vigencias 2008, 2012 y de seguimiento a plan de mejoramiento ambiental en el 2010, se han analizado temáticas de importancia ambiental como la gestión en residuos sólidos. -

Cifras Del Proyecto Beneficios Del Proyecto

Túnel Pavas Peaje Cordillera Pavas Túnel Cresta de Gallo Puente voladizos sucesivos Vista general Unidad Funcional 3 Beneficios del Proyecto Cifras del Proyecto Aumento del potencial ambiental, turístico y cultural en la Ruta de los Vientos. La Vía Mulaló Loboguerrero es un Proyecto de Interés Nacional Estratégico y forma parte de los objetivos del Plan Nacional de Desarrollo, con los más altos estándares de ingeniería, manejo ambiental y social, beneficiará princi- Ejecución del Plan de Gestión Social a través de la implementación de nueve (9) palmente la ciudad de Santiago de Cali y los municipios de Yumbo, La Cumbre y Dagua. programas sociales dirigidos a las comunidades asentadas en el área de influencia del Proyecto. Contrato de Concesión bajo el esquema de Alianza Público Privada APP No. 001 de 2015 Ejecución del Plan de Responsabilidad Ambiental y Social (PRAS). Yumbo, La Cumbre y Dagua en el Valle del Cauca Diversificar, conectar e impulsar la economía en las poblaciones y zonas rurales ubica- das dentro del área de influencia del Proyecto. Conectar los territorios para impulsar los intercambios culturales, sociales y económi- cos entre ellos. Durante el pico máximo de la Fase de Construcción, generación de 1.800 empleos directos. Inversiones para el mejoramiento ambiental. Optimización en los tiempos de recorrido entre Cali y Buenaventura, con una reducción aproximada de 52 km o 1 hora. Incremento de la competitividad y disminución de los costos de operación en el trans- porte de carga. Aprovechamiento de los acuerdos comerciales firmados por Colombia con otros países. Área de Servicio y Centro de Control de Operaciones CCO Oficina de Atención al Usuario: Calle 4 No. -

Informe De Gestión - 2020

DEPARTAMENTO DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA Versión 1.0 INFORME DE GESTION 2020 17/01/2020 VALLECAUCANA DE AGUAS S.A. E.S.P. PROGRAMA AGUA PARA LA PROSPERIDAD PLAN DEPARTAMENTAL DE AGUA DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA PAP-PDA INFORME DE GESTIÓN - 2020 SANTIAGO DE CALI, FEBRERO DE 2020 DEPARTAMENTO DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA Versión 1.0 INFORME DE GESTION 2020 17/01/2020 VALLECAUCANA DE AGUAS S.A. E.S.P. INFORME DE GESTIÓN – 2020 La política para el sector de agua potable y saneamiento básico - “Agua para la Prosperidad” en el Valle del Cauca se lleva a cabo por parte del Gobierno Departamental a través de Vallecaucana de Aguas S.A. E.S.P., entidad creada mediante escritura pública No. 4792 de octubre de 2009, con un capital suscrito y pagado de $500 millones, de los cuales el 94.4% ($472.000.000) corresponde a la Gobernación y el 5.6% restante ($28.000.000) a 14 municipios, a saber: Alcalá, Andalucía, Ansermanuevo, Argelia, Buga, Bugalagrande, El Águila, El Cairo, La Cumbre, Riofrio, San Pedro, Sevilla, Toro y Vijes. VALLECAUCANA DE AGUAS S.A. E.S.P. PARTICIPACIÓN ACCIONARIA No. ACCIONISTAS Porcentaje 1 MUNICIPIO DE ALCALA 0,4% 2 MUNICIPIO DE ANDALUCIA 0,4% 3 MUNICIPIO DE ANSERMANUEVO 0,4% 4 MUNICIPIO DE ARGELIA 0,4% 5 MUNICIPIO DE BUGA 0,4% 6 MUNICIPIO DE BUGALAGRANDE 0,4% 7 MUNICIPIO DE EL AGUILA 0,4% 8 MUNICIPIO DE EL CAIRO 0,4% 9 MUNICIPIO DE LA CUMBRE 0,4% 10 MUNICIPIO DE RIOFRIO 0,4% 11 MUNICIPIO DE SAN PEDRO 0,4% 12 MUNICIPIO DE SEVILLA 0,4% 13 MUNICIPIO DE TORO 0,4% 14 MUNICIPIO DE VIJES 0,4% 15 DEPARTAMENTO DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA 94,4% TOTAL 100,0% Vallecaucana -

Información Del Dane En La Toma De Decisiones De Los Municipios Del País

LA INFORMACIÓN DEL DANE EN LA TOMA DE DECISIONES DE LOS MUNICIPIOS DEL PAÍS Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca Marzo 2020 I N F O R M A C I Ó N P A R A T O D O S Marco conceptual para la confianza en las estadísticas oficiales Precisión Oportunidad Confiabilidad Hay que generar capacidades para Confianza Credibilidad en la construir y mantener la confianza, en producción Objetividad estadística tres niveles: Pertinencia Confianza en Coherencia las estadísticas Sistema Estadístico oficiales Confidencialidad Integridad Confianza en Organización Transparencia las Imparcialidad instituciones estadísticas Normas Relacionamiento con culturales grupos de interés Individuo Conciencia Experiencia/ historia Fuente: OECD framework for trust in official statistics, OECD (2011) Sistema Estadístico Nacional - SEN I N F O R M A C I Ó N P A R A T O D O S Regulación del SEN 2.0 Incorporar enfoque diferencial y territorial en la producción de Artículo 155 de la Ley 1955 de 2019. información estadística. Asegurar la Promover la producción y coordinación difusión de entre los estadísticas oficiales miembros. requeridas por el país. Promover el Aprovechar conocimiento, los registros acceso y uso de administrativos las estadísticas y crear registros oficiales. estadísticos. I N F O R M A C I Ó N P A R A T O D O S Principios del SEN 2.0 • Calidad Del nivel central y territorial • Coherencia • Coordinación Parágrafo 6°. «Brindará asesoría y asistencia técnica en la formulación de • Eficiencia Planes Estadísticos Territoriales, así como en los lineamientos y estándares -

Dirección Cod

Kg Kg Kg Dirección Cod. Punto Punto de Nombre del Despachados Despachados Despachados Total Municipio Centro Zonal Punto de Telefono de Entrega Entrega Responsable Bienestarina Bienestarina Bienestarina Despachado Entrega MAS MAS Fresa MAS Vainilla KATHERINE CL 3 0 0 CZ HI VECINAL 2004381- Alcala 7613020306 YISED CARRERA 45,0 - - 45,0 CARTAGO RISITAS 3206667759 VALENCIA 12 ESQUINA FUNDAPRE luz maria Ansermanue CZ 7613041312 ANSERMAN ocampo CL 12 C 6 32 -3104299603 157,5 45,0 - 202,5 vo CARTAGO UEVO suaza CABILDO INDIGENA CZ luis evelio VDA. LA 3207292740- Argelia 7613054328 EMBERA 22,5 - - 22,5 CARTAGO gutierrez SOLEDAD 3117835087 CHAMI ARGELIA luz ariela CZ FUNDAPRE Argelia 7613054330 herrera CL 2 N 6 62 -3117354600 67,5 22,5 - 90,0 CARTAGO ARGELIA herrera A I C CZ CORREGIMI ASOCIACIÓ ABELINO 3188270622- Bolivar ROLDANILL 7600100004 ENTO 45,0 - - 45,0 N INDIGENA AIZAMA 3123087237 O NARANJAL DEL CAUCA HOGAR FRANCIA CZ 7600100000 INFANTIL ELENA 2224087- Bolivar ROLDANILL CL 7 5 72 225,0 90,0 - 315,0 1 PATITOS ÁLVAREZ 3113822919 O TRAVIESOS RINCÓN KR 37 CALLE 7 NO 2428353244 CZ MILADIS Buenaventur 7C 58 8970- BUENAVEN 7614109018 JUAN XXIII ALOMIA 90,0 - 22,5 112,5 a BARRIO 3174488790 TURA HURTADO JARDIN C 3147295916 ESTE 37 K 7 CL 1 KR16 BARRIO LA PLAYITA PUENTE CZ MARTHA LOS - Buenaventur GUABITO BUENAVEN 7614109021 CECILIA NAYEROS B 3153839048 67,5 - 22,5 90,0 a DOS TURA ALEGRIA SUR 1 1 3186500000 ESTE CALLE 1 KR 16 BARRIO LA PLAYITA CL CALLE 4 LUZ NO 13 22 CZ Buenaventur GUABITO AMPARO BARRIO 3154403761- BUENAVEN 7614109022 112,5 - 22,5 -

Pliocene Impact Crater Discovered in Colombia: Geological, Geophysical and Seismic Evidences

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) 2466.pdf PLIOCENE IMPACT CRATER DISCOVERED IN COLOMBIA: GEOLOGICAL, GEOPHYSICAL AND SEISMIC EVIDENCES. J. Gómez1, A. Ocampo2, V. Vajda3, J. A. García4, A. Lindh5, A. Scherstén5, A. Pitzsch6, L. Page5, A. Ishikawa7, K. Suzuki8, R. S. Hori9, M. Buitrago10, J. A. Flores10 and D. Barrero11; 1Colombian Geologi- cal Survey, Diagonal 53 #34–53 Bogotá, Colombia ([email protected]); 2NASA HQ, Science Mission Direc- torate, Washington DC 20546, US; 3Department of Palaeobiology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, SE–104 05 Stockholm, Sweden; 3Universidad Libre, Sociedad Astronómica ANTARES, Cali, Colombia; 5Department of Geol- ogy, Lund University, Sweden; 6MAX–lab, Lund University, Sweden/ Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin, Institute Methods and Instrumentation for Synchrotron Radiation Research, Berlin, Germany; 7Department of Earth Science & As- tronomy, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Japan; 8IFREE/SRRP, Japan Agency for Marine–Earth Science and Technology, Natsushima, Yokosuka 237–0061, Japan; 9Department of Earth Science, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Ehime University, 790–8577, Japan; and 10Department of Geology, University of Salamanca, Spain and 11Consultant geologist, Bogotá, Colombia. Introduction: The paleontological record clearly sedimentites; (8) Triassic intrusive; and (9) Permian to reveals that impacts of large extra–terrestrial bodies Cretaceous metamorphic rocks. may cause ecosystem devastation at a global scale [1], The impact crater and the local geology: The whereas smaller impacts have more local consequenc- Cali Crater is located in the Cauca Sub–Basin between es depending on their size, impact angle and composi- the Western and Central Colombian cordilleras, SE of tion of the target rocks [2]. -

Plan De Desarrollo 2016-2019

1 TABLA DE CONTENIDO DIAGNÓSTICO ....................................................................................................................... 4 Reseña histórica ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Geografía: ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ecología: ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Economía: ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 Vías de comunicación: .................................................................................................................................... 8 1. DIMENSIÓN POBLACIONAL............................................................................................ 9 II. DIMENSIÓN SOCIAL ...................................................................................................... 133 2 OBJETIVO ................................................................................................................................................ 1313 1. Educación. .................................................................................................................................................... 13 2. Salud. -

Valle Del Cauca

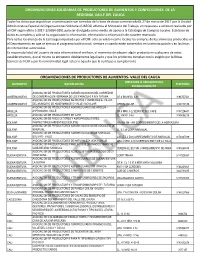

ORGANIZACIONES SOLIDARIAS DE PRODUCTORES DE ALIMENTOS Y CONFECCIONES DE LA REGIONAL VALLE DEL CAUCA Todos los datos que se publican a continuación son tomados de la base de datos suministrada EL 27 de marzo de 2017 por la Unidad Administrativa Especial de Organizaciones Solidarias (UAEOS) adscrita al Ministerio del Trabajo, en respuesta a solicitud realizada por el ICBF según oficio S-2017-123684-0101 para ser divulgada como medio de apoyo a la Estrategia de Compras Locales. Esta base de datos es completa y sólo se ha organizado la información, eliminando la información de caracter reservado. Para todos los efectos de la Estrategia impulsada por el ICBF, sólo se validan como locales las compras de los alimentos producidos en el Departamento en que se ejecuta el programa institucional, siempre y cuando estén contenidos en la minuta patrón y en las listas de intercambio autorizadas. Es responsabilidad del usuario de esta información el verificar, al momento de adquirir algún producto en cualquiera de estos establecimientos, que el mismo se encuentre debidamente legalizado y que los productos cumplan con lo exigido por la fichas técnicas del ICBF y por la normatividad legal actual o aquella que la sustituya o complemente. ORGANIZACIONES DE PRODUCTORES DE ALIMENTOS- VALLE DEL CAUCA DIRECCION O UBICACION DEL MUNICIPIO RAZON SOCIAL TELEFONO ESTABLECIMIENTO ASOCIACION DE PRODUCTORES AGROECOLOGICOS DEL CORREDOR ANSERMANUEVO DE CONSERVACION SERRANIA DE LOS PARAGUAS P.N.N TATAMA CR 4 BIS NRO. 6-91 3196757561 ASOCIACION DE PRODUCTORES DE FRUTAS Y VERDURAS EL VILLAR ANSERMANUEVO DEL MUNICIPIO DE ANSERMANUEVO VALLE ASOVILLAR CRR EL VILLAR 3148110178 ASOCIACION DE PRODUCTORES AGROPECUARIOS DE ARGELIA - ARGELIA ASPROAGRO- VALLE CR 5 NRO.3-22 EDIFICIO DEL CAFE 3137224647 ARGELIA ASOCIACION DE PRODUCTORES DE CAFE CL 3 NRO. -

Persisten Amenazas De Muerte Contra Candidatos En El Valle Del Cauca

http://www.elpais.com.co/elpais/judicial/persisten-amenazas-muerte-contra-candidatos-en-valle- del-cauca 11-08-24 Persisten amenazas de muerte contra candidatos en el Valle del Cauca El defensor nacional del Pueblo, Vólmar Pérez, dijo que los mayores riesgos están en El Dovio, Roldanillo, Tuluá, Sevilla, Riofrío y Cali. Preocupa el accionar de las Farc, Las Farc, ‘Los Rastrojos’, ‘Los Machos’ y los ‘Urabeños’. Por: ColprensaMiércoles, Agosto 24, 2011 - 2:51 p.m. Ampliar El diputado del Valle Fernando Vargas, aspirante al Concejo de Yumbo, fue asesinado en el norte de Cali. Aymer Álvarez | El País. Como una evidencia de los problemas de seguridad que afrontan los candidatos a cargos de elección popular en el Valle del Cauca calificó el defensor del Pueblo, Vólmar Pérez, el asesinato del candidato al concejo Municipal de Cali Nicolai Vera Rico, de 25 años, ocurrida en la noche del martes. Pérez Ortíz condenó la muerte de Vera Rico y señaló que los riesgos para los candidatos son mayores en los municipios de El Dovio, Roldanillo, Tulúa, Sevilla, Riofrío y Cali. En la zona preocupa el accionar de Las Farc, ‘Los Rastrojos’, ‘Los Machos’ y los ‘Urabeños’. “Esto obliga a la fuerza pública a fortalecer las medidas para garantizar con la efectividad que se requiere el derecho a la vida y la integridad personal de los candidatos, así como a disuadir los riesgos de las amenazas”, señaló la Defensoría. Según la entidad, en el Valle han sido asesinados ya siete candidatos (dos candidatos en El Dovio y dos en el Riofrío), hubo un atentado contra el exalcalde local Néstor José Loaiza y otro contra el conductor del alcalde El Dovio, hecho que provocó su desplazamiento. -

Inversiones En El Departamento Del Valle Del

Inversiones en el departamento del Valle del Cauca 2010 – 2016 Entre 2010 y 2015 se destinaron $ 143.362 millones para el sector cultural del departamento del Valle del Cauca, entre recursos del Ministerio de Cultura y fuentes de financiación como: entre recursos del Ministerio de Cultura y fuentes de financiación como: impuesto nacional al consumo de la telefonía móvil, sistema general de participantes, sistema general de regalías, los proyectos Espacios de Vida y Cultura en los Albergues de Colombia Humanitaria y MinCultura, recursos de la Ley del Espectáculo Público, Infraestructura Cultura y la intervención a la Plaza de Mercado en Buenaventura. Dicha inversión permitió la construcción y el fortalecimiento de 36 obras de infraestructura cultural en este departamento, entre las cuales se destacan: la construcción de las Bibliotecas Públicas en los municipios de Buga, Buenaventura, Cali, Florida, Pradera, Candelaria, Trujillo, Vijes, rehabilitación de las bibliotecas en Cali y Guacarí, rehabilitación de las Casas de Cultura de Calima el Darién, Dagua, Guacarí, Jamundí, Tuluá, Versalles y La Victoria, intervención centros culturales en Cali (Manzana del saber, Somos Pacífico y Parque Lineal Comuna 18), remodelación del Parque Bolívar y la semi -peatonalización Carrera 13 en Buga, Escuelas de música en Cali, Yotocó y Candelaria (Esta última continúa en la vigencia 2016) y Salones de danza entregados en los municipios de Obando, Palmira y Tuluá y adecuación salón de danza municipio de La Victoria. Adecuación de los Museos La Tertulia en Cali, el Museo Rayo en Roldanillo, y el Teatrino Comuna 16 de Cali, intervención BIC Nacional Estación de Ferrocarril de Buenaventura y la Hacienda Cañas Gordas en Cali, Intervención de la Plaza de Mercado del Municipio de Buenaventura (Convenio firmado con FONTUR - Valor total del proyecto: $10.732 millones) y los estudios técnicos y proyecto de restauración integral de la estación de ferrocarril de Bugalagrande. -

Evidencias Del Desarrollo Socioeconómico Del Valle Del Cauca

Evidencias del desarrollo socioeconómico del Valle del Cauca FORO ECONÓMICO SECTORIAL – CAMACOL Cali, Valle del Cauca Enero 29 de 2020 I N F O R M A C I Ó N P A R A T O D O S Potencialidades de la información estadística con enfoque territorial Para evidenciar características y condiciones específicas de la La información estadística población que deben ser tenidas en cuenta en la definición de es un activo fundamental en la estrategias de desarrollo locales. formulación de los Planes de Desarrollo Territorial. Para asegurar la calidad de la información que sirve como insumo en la toma de decisiones clave de los territorios; por ejemplo, la definición de impuestos, generación de incentivos para determinados sectores y actividades productivas deben apalancarse en datos. Para contar con información a un mayor nivel de desagregación territorial que permite la focalización de las políticas; por ejemplo, para reducción de la pobreza multidimensional. Para su uso como soporte de procesos de construcción participativa sobre las soluciones sociales, la optimización de procesos de rendición de cuentas, y para garantizar la transparencia de la gestión pública. I N F O R M A C I Ó N P A R A T O D O S ¿Quiénes son los actores involucrados en el fortalecimiento estadístico del territorio? Asambleas departamentales y concejos Ciudadanía municipales Entes de control Beneficiarios Beneficiarios Organizaciones directos indirectos de la sociedad Administraciones civil locales: .Gobernaciones .Alcaldías Agremiaciones Entidades del orden nacional Academia