Winchester & the First Foreign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

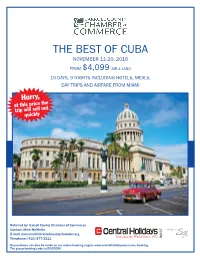

The Best of Cuba

THE BEST OF CUBA NOVEMBER 11-20, 2016 FROM $4,099 AIR & LAND 10 DAYS, 9 NIGHTS INCLUDING HOTELS, MEALS, DAY TRIPS AND AIRFARE FROM MIAMI Hurry, this price the at t trip will sell ou quickly Referred by: Carroll County Chamber of Commerce Contact: Mike McMullin Member of E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (410) 977-3111 Reservations can also be made on our online booking engine www.centralholidayswest.com/booking. The group booking code is: B002054 THE BEST OF CUBA 10 DAYS/9 NIGHTS from $4,099 air & land (1) MIAMI – (3) HAVANA – (3) SANTIAGO DE CUBA – (2) CAMAGUEY FLORIDA 1 Miami Havana 3 Viñales Pinar del Rio 2 CUBA Camaguey Viñales Valley 3 Santiago de Cuba # - NO. OF OVERNIGHT STAYS Day 1 Miami Arrive in Miami and transfer to your airport hotel on your own. This evening in the hotel lobby meet your Central Holidays Representative who will hold a mandatory Cuba orientation meeting where you will receive your final Cuba documentation and meet your traveling companions. TOUR FEATURES Day 2 Miami/Havana This morning, transfer to Miami International Airport •ROUND TRIP AIR TRANSPORTATION - Round trip airfare from – then board your flight for the one-hour trip to Havana. Upon arrival at José Miami Martí International Airport you will be met by your English-speaking Cuban escort and drive through the city where time stands still, stopping at •INTER CITY AIR TRANSPORTATION - Inter City airfare in Cuba Revolution Square to see the famous Che Guevara image with his well-known •FIRST-CLASS ACCOMMODATIONS - 9 nights first class hotels slogan of “Hasta la Victoria Siempre” (Until the Everlasting Victory, Always) (1 night in Miami, 3 nights in Havana, 3 nights in Santiago lives. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

CUBA by LAND and by SEA an EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE-TO-PEOPLE EXPERIENCE Accompanied by PROFESSOR TIM DUANE

CUBA BY LAND AND BY SEA AN EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE-TO-PEOPLE EXPERIENCE Accompanied by PROFESSOR TIM DUANE UNESCO UNITED STATES Deluxe Small Sailing Ship World Heritage Site FLORIDA Air Routing Miami Cruise Itinerary Land Routing Gulf of Mexico At Viñales Valley lan Havana ti CUBA c O ce Santa Clara an Pinar del Río Cienfuegos Trinidad Caribbean Sea Santiago de Cuba Be among the privileged few to join this uniquely designed people-to-people itinerary, featuring a six-night cruise from Santiago de Cuba along the island’s southern coast followed Itinerary by three nights in the spirited capital city of Havana—an February 3 to 12, 2019 extraordinary opportunity to traverse the entire breadth Santiago de Cuba, Trinidad, Cienfuegos, Santa Clara, of Cuba. Beneath 16,000 square feet of billowing white canvas, sail aboard the exclusively chartered, three-masted Havana, Pinar del Río Le Ponant, featuring only 32 deluxe Staterooms. Enjoy an Day unprecedented people-to-people experience engaging 1 Depart the U.S./Arrive Santiago de Cuba, Cuba/ local Cubans and U.S. travelers to share commonalities Embark Le Ponant and experience firsthand the true character of the Caribbean’s largest and most complex island. In Santiago de 2 Santiago de Cuba Cuba, visit UNESCO World Heritage-designated El Morro. 3 Santiago de Cuba See the UNESCO World Heritage sites of Old Havana, 4 Cruising the Caribbean Sea Cienfuegos, Trinidad and the Viñales Valley. Accompanied by an experienced, English-speaking Cuban host, 5 Trinidad immerse yourself in a comprehensive and intimate travel 6 Cienfuegos for Santa Clara experience that explores the history, culture, art, language, cuisine and rhythms of daily Cuban life while interacting 7 Cienfuegos/Disembark ship/Havana with local Cuban experts including musicians, artists, 8 Havana farmers and academics. -

The Spanish- American War

346-351-Chapter 10 10/21/02 5:10 PM Page 346 The Spanish- American War MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Terms & Names In 1898, the United States U.S. involvement in Latin •José Martí •George Dewey went to war to help Cuba win America and Asia increased •Valeriano Weyler •Rough Riders its independence from Spain. greatly as a result of the war •yellow journalism •San Juan Hill and continues today. •U.S.S. Maine •Treaty of Paris One American's Story Early in 1896, James Creelman traveled to Cuba as a New York World reporter, covering the second Cuban war for independ- ence from Spain. While in Havana, he wrote columns about his observations of the war. His descriptions of Spanish atrocities aroused American sympathy for Cubans. A PERSONAL VOICE JAMES CREELMAN “ No man’s life, no man’s property is safe [in Cuba]. American citizens are imprisoned or slain without cause. American prop- erty is destroyed on all sides. Wounded soldiers can be found begging in the streets of Havana. The horrors of a barbarous struggle for the extermination of the native popula- tion are witnessed in all parts of the country. Blood on the roadsides, blood in the fields, blood on the doorsteps, blood, blood, blood! . Is there no nation wise enough, brave enough to aid this blood-smitten land?” —New York World, May 17, 1896 Newspapers during that period often exaggerated stories like Creelman’s to boost their sales as well as to provoke American intervention in Cuba. M Cuban rebels burn the town of Jaruco Cubans Rebel Against Spain in March 1896. -

Unmapping Knowledge: Connecting Histories About Haitians in Cuba

OLÍVIA MARIA GOMES DA CUNHA Unmapping knowledge: connecting histories about Haitians in Cuba This article is an exercise in comparing narratives that depict the ‘presence’ of Haitians in Cuba. It focuses on the creative forms through which groups of residentes and descendientes, formally designated asociaciones, are experimenting with new modes of creating relationships with kin, histories, places and times. Rather than emerging exclusively from the memories of past experiences of immigration and the belonging to ‘communities’, these actors seem to emphasise that histories apparently associating them with certain bounded existential territories can in fact be created and recreated in multiple forms, mediated by diverse objects and events, and apprehended through a critical perspective, albeit one subject to personal interpretations. Key words ethnography, history, Cuba, knowledge, migration Introduction In an old building in downtown Havana, around the end of 2004, a group of about ten people gather every week to rehearse presentations of Creole songs and dances. This small collective formed part of a larger group called Dessaline, whose members are children and grandchildren of Haitian immigrants. During one of their rehearsals, Felicia told me how a friend’scravingfora dish of Haitian origin had put her in contact with countless paisanos (‘fellow countrymen’) living in Havana. Far from the Cuban capital, on the outskirts of the city of Villa Morena, a group of pensioners would also meet regularly to hear and discuss Haitian history. Every month, and on special commemorative dates, an asociación (‘association’) called Los Hatianos (hereafter LH) organised meetings of local residentes (as those born in Haiti are called) and descendientes (chil- dren of Haitians born in Cuba). -

Florida Cuban Heritage Trail = Herencia Cubana En La Florida

JOOOw OCGO 000 OGCC.Vj^wjLivJsj..' Florida ; Herencia Cuban : Clmva Heritage ; en la Trail ; ftcMm ^- ^ . j.lrfvf. "^»"^t ;^ SJL^'fiSBfrk ! iT^ * 1=*— \ r\+ mi,.. *4djjk»f v-CCTIXXXIaXCCLl . , - - - - >i .. - ~ ^ - - ^ ^v'v-^^ivv^VyVw ViiuvLLcA rL^^LV^v.VviL'ivVi florida cuban heritage trail La Herencia Cubana En La Florida Cuban Americans have played a significant role Los cubano-americanos han jugado un papel muy in the development of Florida dating back to significativo en el desarrollo de la Florida, que se the days of Spanish exploration. Their impact remonta a la epoca de la exploration espahola. El on Florida has been profound, ranging from influences in impacto de los cubanos en la Florida ha sido profundo en el architecture and the arts to politics and intellectual thought. dmbito de la arquhectura, las artes, la cultura, la politica y la Many historic sites represent the patriotism, enterprise intelectualidad. Muchos de los lugares aquialudidos son pruebas and achievements of Cuban Americans and the part they del patriotismo, la iniciativa y los logros de los cubano americanos have played in Florida's history. y el papel que han desempehado en la historia de este estado. In 1994, the Florida Legislature funded the Florida Cuban En 1994 la legislatura estatal proportions los fondos para la Heritage Trail to increase awareness of the connections publication de La Herencia Cubana en la Florida. El between Florida and Cuba in the state's history. The proposito del libro es dar a conocer la conexion historica entre Cuban Heritage Trail Advisory Committee worked closely Cuba y la Florida. -

China Behind Raúl's Economic Reforms, Says Expert in Chinese

Vol. 21, No. 7 July 2013 In the News China behind Raúl’s economic reforms, Reforms announced says expert in Chinese-Cuban relations DeregUlation of state firms to begin; GDP BY VITO ECHEVARRÍA another 1,000 bUses in 2008 — replacing the infamoUs hUmp-shaped bUses Univer- growth forecast downgraded .......Page 4 verage CUbans can now sell hoUses and “camello” apartments to each other, bUdding entre- sally hated by habaneros. There was also a 2006 deal in which Chinese ApreneUrs may offer goods and services Political briefs manUfactUrer Haier sUpplied CUba with 300,000 directly to consUmers — withoUt going throUgh new energy-efficient refrigerators, as part of the GOP tries to restrict travel to CUba; revived the state — and the island’s new immigration Castro regime’s plan to finally rid the island of interest in CUba certified claims ...Page 5 law permits foreign real-estate owners and long- antiqUated, mostly American-made fridges. term renters to obtain renewable visas. “These kinds of trade interactions have been AUstralian academic Adrian Hearn says all accompanied by some pretty intensive dialogUe Corruption on trial these people can thank the Chinese for pUshing with China aboUt how the [CUban] economy can Canadian expert Gregory Biniowsky says President Raúl Castro to reform the economy. develop,” Hearn said. Raúl’s anti-corrUption campaign is good for Speaking May 22 at New York’s CUNY “This has been happening since 1995 when GradUate School, Hearn explained how China Fidel Castro visited Beijing and met Prime foreign investors in long rUn .........Page 6 — along with VenezUela — has become a vital Minister Li Pong, who advised him in no Uncer- economic lifeline for CUba. -

Tactical Negrificación and White Femininity

Tactical Negrificación and White Femininity Race, Gender, and Internationalism in Cuba’s Angolan Mission Lorraine Bayard de Volo At the ideological heart of the Cuban Revolution is the commitment to liberation from oppressive systems at home and abroad. From early on, as it supported anti- imperialist struggles, revolutionary Cuba also officially condemned racism and sex- ism. However, the state’s attention to racism and sexism has fluctuated—it has been full-throated at times, silent at others. In considering Cuba’slegacy,thisessayexam- ines gender and race in its international liberatory efforts while also considering the human costs of armed internationalism. Why did women feature prominently in some instances and not others? As a “post-racial” society where “race doesn’t mat- ter,” how are we to understand those occasions in which race officially did matter? I focus on Cuba’s Angola mission (1975–91) to explore the revolution’s uneven attention to gender and race.1 Rather than consistently battling inequities, the state approached gender and racial liberation separately and tactically, as means to military, political, and diplomatic ends. Through negrificación (blackening) of national identity, Cuba highlighted race to internationally legitimize and domesti- cally mobilize support for its Angola mission.2 In contrast, despite their high profile in the Cuban insurrection of the 1950s and 1980s defense, women were a relatively minor theme in the Angolan mission. Several prominent studies note the international factors behind Cuba’s racial politics, but they have a domestic focus, leaving international dynamics relatively Radical History Review Issue 136 (January 2020) DOI 10.1215/01636545-7857243 © 2020 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc. -

Cuba, Primarily from the 19Th Century

Our latest cataogue is devoted to works from and about Cuba, primarily from the 19th century. It includes unusual and rare imprints -- many of them unrecorded -- not only from Havana, but also Guanabacoa, Cienfuegos, Puerto-Principe, and Matanzas, as well as manuscript material and photography. Highlights include a rare Cuban cook book illustrated with plates; a rare bilingual guidebook published in Havana in 1899, with a handsome map; an unusual literary manuscript; an archive of mining photographs featuring local people and scenery; the archive of a Cuban planter from the early 19th-century; a photographically illustrated work on the Cuban Revolution published in 1872; a rare annual guide to Cuba from 1809 located in one other copy; and many List 25 | Cuba more interesting pieces. Enjoy! Cheers, Teri & James Terms of Sale All items are guaranteed as described. Any purchase may be returned for a full refund within 10 working days as long as it is returned in the same condition and is packed and shipped correctly. All items subject to prior sale. We accept payment by check, wire transfer, and all major credit cards. Payment by check or wire is preferred. Sales tax charged where applicable. McBride Rare Books New York, New York [email protected] (203) 479-2507 www.mcbriderarebooks.com Copyright © 2021, McBride Rare Books, LLC. RARE CUBAN COOK BOOK, WITH PLATES delicado gusto, saben apreciar su mérito; sino aun de aquellos que, atormentados cruelmente y estenuados por la inapetencia, ven el puerto 1. Coloma y Garces, Eugenio de. Manual del Cocinero Cubano, y de su salvacion en este arte encantador que, como las famosas sirenas de Repertorio Completo y Escogido de los Mejores Tratados Modernos Virgilio, atrae para sí la víctima ya próxima á sucumbir, y le da una nueva del Arte de Cocina Española, Americana, Francesa, Inglesa, Italiana vida separandolo repentinamente de la guadaña que lo encamina á su y Turca, Arreglado al Uso, Costumbres y Temperamento de la Isla de deplorable fin. -

Cuba, the United States, and the World

Pérez, Louis A., Jr. 2019. To Disquiet a Giant: Cuba, the United States, and the World. Latin American Research Review 54(4), pp. 1039–1046. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.603 BOOK REVIEW ESSAYS To Disquiet a Giant: Cuba, the United States, and the World Louis A. Pérez Jr. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, US [email protected] This essay reviews the following works: From Lenin to Castro, 1917–1959: Early Encounters between Moscow and Havana. By Mervyn J. Bain. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013. Pp. vii + 159. $55.99 hardcover. ISBN: 9780739181102. Cuba’s Revolutionary World. By Jonathan C. Brown. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017. Pp. vi + 586. $35.00 hardcover. ISBN: 9780674971981. Cubans in Angola: South-South Cooperation and Transfer of Knowledge, 1976–1991. By Christine Hatzky. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2015. Pp. v + 386. $39.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780299301040. Exporting Revolution: Cuba’s Global Solidarity. By Margaret Randall. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017. Pp. x + 272. $25.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780822369042. U.S.-Cuba Relations: Charting a New Path. By Jonathan D. Rosen and Hanna S. Kassab. Baltimore, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016. Pp. vii + 164. $36.99 paperback. ISBN: 9781498537759. How small things may annoy the greatest! Even a mouse troubles an elephant; a gnat, a lion: a very flea may disquiet a giant. —Joseph Hall, The Works of Joseph Hall: Latin Theology with Translation (1839) To contemplate a body of scholarship dedicated to the subject of Cuban foreign relations is at first blush to ponder an unlikely field of study.