Tactical Negrificación and White Femininity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

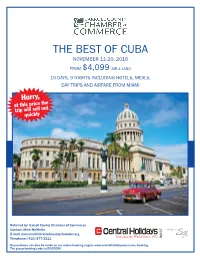

The Best of Cuba

THE BEST OF CUBA NOVEMBER 11-20, 2016 FROM $4,099 AIR & LAND 10 DAYS, 9 NIGHTS INCLUDING HOTELS, MEALS, DAY TRIPS AND AIRFARE FROM MIAMI Hurry, this price the at t trip will sell ou quickly Referred by: Carroll County Chamber of Commerce Contact: Mike McMullin Member of E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (410) 977-3111 Reservations can also be made on our online booking engine www.centralholidayswest.com/booking. The group booking code is: B002054 THE BEST OF CUBA 10 DAYS/9 NIGHTS from $4,099 air & land (1) MIAMI – (3) HAVANA – (3) SANTIAGO DE CUBA – (2) CAMAGUEY FLORIDA 1 Miami Havana 3 Viñales Pinar del Rio 2 CUBA Camaguey Viñales Valley 3 Santiago de Cuba # - NO. OF OVERNIGHT STAYS Day 1 Miami Arrive in Miami and transfer to your airport hotel on your own. This evening in the hotel lobby meet your Central Holidays Representative who will hold a mandatory Cuba orientation meeting where you will receive your final Cuba documentation and meet your traveling companions. TOUR FEATURES Day 2 Miami/Havana This morning, transfer to Miami International Airport •ROUND TRIP AIR TRANSPORTATION - Round trip airfare from – then board your flight for the one-hour trip to Havana. Upon arrival at José Miami Martí International Airport you will be met by your English-speaking Cuban escort and drive through the city where time stands still, stopping at •INTER CITY AIR TRANSPORTATION - Inter City airfare in Cuba Revolution Square to see the famous Che Guevara image with his well-known •FIRST-CLASS ACCOMMODATIONS - 9 nights first class hotels slogan of “Hasta la Victoria Siempre” (Until the Everlasting Victory, Always) (1 night in Miami, 3 nights in Havana, 3 nights in Santiago lives. -

Cuba Travelogue 2012

Havana, Cuba Dr. John Linantud Malecón Mirror University of Houston Downtown Republic of Cuba Political Travelogue 17-27 June 2012 The Social Science Lectures Dr. Claude Rubinson Updated 12 September 2012 UHD Faculty Development Grant Translations by Dr. Jose Alvarez, UHD Ports of Havana Port of Mariel and Matanzas Population 313 million Ethnic Cuban 1.6 million (US Statistical Abstract 2012) Miami - Havana 1 Hour Population 11 million Negative 5% annual immigration rate 1960- 2005 (Human Development Report 2009) What Normal Cuba-US Relations Would Look Like Varadero, Cuba Fisherman Being Cuban is like always being up to your neck in water -Reverend Raul Suarez, Martin Luther King Center and Member of Parliament, Marianao, Havana, Cuba 18 June 2012 Soplillar, Cuba (north of Hotel Playa Giron) Community Hall Questions So Far? José Martí (1853-95) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Che Guevara (1928-67) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Derek Chandler International Airport Exit Doctor Camilo Cienfuegos (1932-59) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Havana Museo de la Revolución Batista Reagan Bush I Bush II JFK? Havana Museo de la Revolución + Assorted Locations The Cuban Five Havana Avenue 31 North-Eastbound M26=Moncada Barracks Attack 26 July 1953/CDR=Committees for Defense of the Revolution Armed Forces per 1,000 People Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12 Questions So Far? pt. 2 Marianao, Havana, Grade School Fidel Raul Che Fidel Che Che 2+4=6 Jerry Marianao, Havana Neighborhood Health Clinic Fidel Raul Fidel Waiting Room Administrative Area Chandler Over Entrance Front Entrance Marianao, Havana, Ration Store Food Ration Book Life Expectancy Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Cuba: Carnaval Cuban Style

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS 535 Fifth Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 FJM-30: Cuba Havana, Cuba Carnaval Cub an Style July 20, 1971 2. FJM-30 In December 1970, while speaking before an assembly of light industry workers, Fidel told the Cubans that for the second year in a row they would have to cancel Christmas and New Year celebrations. Instead, there would be Carnaval in July. "We'd love to celebrate New Year's Eve, January i and January 2. Naturally. Who doesn't? But can we afford such luxuries now, the way things stand? There is a reality. Do we have traditions? Yes. Very Christian traditions? Yes. Very beautiful traditions? Very poetic traditions? Yes, of course But gentlemen, we don't live in Sweden or Belgium or Holland. We live in the tropics. Our traditions were brought in from Europe--eminently respectable traditions and all that, but still imported. Then comes the reality about this country" ours is a sugar- growing country...and sugar cane is harvested in cool, dry weather. What are the best months for working from the standpoint of climate? From November through May. Those who established the tradition listen if they had set Christmas Eve for July 24, we'd .be more than happy. But they stuck everybody in the world with the same tradition. In this case are we under any obligation? Are the conditions in capitalism the same as ours? Do we have to bow to certain traditions? So I ask myself" even wen we have the machines, can we interrupt our work in the middle of December? [exclamations of "No!"] And one day even the Epiphan festivities will be held in July because actually the day the children of this countr were reborn was the day the Revolution triumphed." So this summer there is carnaval in July" Cuban Christmas, New Years and Mardi Gras all in one. -

Strategy for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in the Sadc Region

STRATEGY FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS IN THE SADC REGION Not an ofcial SADC publication STRATEGY FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS IN THE SADC REGION 2019 - 2013 S T R AT E G Y F O R S E X U A L A N D R E P R O D U C T I V E H E A LT H A N D R I G H T S IN THE SADC REGION AN INTERIM PUBLICATION OF THE SADC STRATEGY The strategy remains a work-in-progress as the SADC Technical Working Group begins work early in 2019 on a monitoring and evaluation framework and strategy BROUGHT TO YOU BY: The Civil Society Organisations supporting the SADC SRHR Strategy PAGE 2 SADC SRHR STRATEGY 2019 - 2013 STRATEGY FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS IN THE SADC REGION 2019 - 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The SRHR Strategy for the SADC Region (2019 – 2030) was made possible through the collaboration of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Secretariat with Member States and various stakeholders. The Secretariat acknowledges all contributions in particular the leadership by the Ministries of Health for Eswatini, Namibia and South Africa, who provided strategic direction and support to the work of the Technical Committee comprising of representatives from UN agencies, SheDecides, civil society and youth led organisations who led the development of the strategy. We acknowledge the contribution by representatives from the Ministries of Health, Education, Gender, and Youth from the 15 SADC Member States, Southern African civil society partners , youth led organisations who participate in the Technical Consultation and worked collaboratively to build consensus and provide inputs that has resulted in the development of this draft. -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

Female Representation in the National Parliaments of Angola, Ethiopia and Lesotho

International Journal of Politics and Good Governance Volume 3, No. 3.3 Quarter III 2012 ISSN: 0976 – 1195 THE SUB-SAHARAN AFRICAN TRIUMVIRATE: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN THE NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS OF ANGOLA, ETHIOPIA AND LESOTHO Kimberly S. Adams Associate Professor of Political Science, East Stroudsburg University, USA ABSTRACT From December 5, 2001 to January 31, 2011, the percentage of women serving in the lower chambers of Angola, Ethiopia, and Lesotho, increased by 23.1 percent, 20.1 percent, and 20.4 percent respectively (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2011) While numerous factors can possibly explain this increase, this paper examines political, socioeconomic and cultural factors that may help to explain the increased presence of women in the national parliaments of Angola, Ethiopia, and Lesotho from 2001 to 2011. Unlike my previous works on women serving in national parliament, that employ quantitative analysis when examining the impact of explanatory variables on women in parliaments, this work employs a case study approach to systematically examine the increased share of women in the parliaments of three very different and unique Sub- Saharan African countries. Keywords: Women, African politics, Parliament, Representation, Angola, Ethiopia, Lesotho 1 International Journal of Politics and Good Governance Volume 3, No. 3.3 Quarter III 2012 ISSN: 0976 – 1195 “It is important to understand that, establishing women’s political rights in law does not mean in practice that women will be allowed to exercise those rights.” (Pamela Paxton/Melanie M. Hughes, 2007: 62) Introduction Women in Sub-Saharan African society have been the subject of countless studies in the United States during the past three decades.Topics ranging from domestic abuse, sexual exploitation, government corruption, to Sub-Saharan African women’s access to healthcare, education, the paid workforce and political power, continue to be the focus of governmental reports and academic manuscripts. -

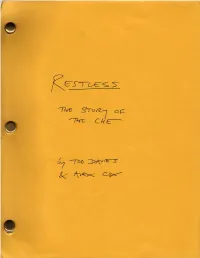

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. GENERAL Council E/C.12/AGO/3 28 April 2008 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH Substantive session of 2008 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS Combined initial, second and third periodic reports, under articles 16 and 17 of the Covenant ANGOLA [16 April 2008] * The present document was not formally edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. ** The annexes to this report may be consulted at the secretariat. GE.08-41548 (EXT) E/C.12/AGO/3 page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. GENERAL PROVISIONS OF THE COVENANT ON ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS .............. 1 - 31 3 II. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE LAW IN PRACTICE: DIFFICULTIES AND CONSTRAINTS ................................... 32 - 101 14 III. STRENGTHENING THE PRODUCTION CAPACITY OF THE TRADITIONAL SECTOR ............................................... 102 - 114 35 IV. REFORMS AND MEASURES IMPLEMENTED ................... 115 - 124 40 V. EMPLOYMENT ........................................................................ 125 - 132 42 VI. ADMINISTRATIVE DECENTRALIZATION AND RE-ESTABLISHMENT OF GOVERNMENT SERVICES NATIONWIDE .......................................................................... 133 - 160 44 VII. INTEGRATED PROGRAMME FOR HOUSING, URBAN DEVELOPMENT, BASIC SANITATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT ...................................................................... 161 - 177 53 VIII. HIV AIDS ................................................................................. -

Slaves and Natives in Gómez De Avellaneda's Sab^

Colonial Others as Cuba's Protonational Subjects: The Privileged Space of Women, Slaves and Natives in Gómez de Avellaneda's Sab^ Kelly Comfort University of California, Davis Throughout Cuban literary history, authors and critics have celebrated racial admixture as representative of the island's unique national character. Beginning most notably with José Martí's "Nuestra Améri- ca" in 1891, one encounters frequent praise of mestizaje and a manifest desire to unite the natives, the newly freed slaves, and the "campesi- nos" or country folk against the foreign element that continued to relégate Cuba to colonial status. More than half a century later, Alejo Carpentier, in his famous 1949 preface to El reino de este mundo, addresses the presence of the "marvelous real" in America and offers further celebration of the Caribbean región as a place that, "[b]ecause of the virginity of the land, our upbringing, our ontology, the Faustian presence of the Indian and the black man, the revelation constituted by the recent discovery, its fecund racial mixing [mestizaje], . is far from using up its wealth of mythologies" (88). Roberto Fernández Retamar, a contemporary Cuban critic, echoes the sentiments of his precursors when he insists that "within the colonial world there exists a case unique to the entire planet: a vast zone for which mestizaje is not an accident but rather an essence, the central line: ourselves, 'our mestizo America' " (4). Ovv^ing to these and many other examples, it has become a commonplace in literary and historical studies to discuss mestizaje as a defining characteristic of Cuban national identity. -

CUBA by LAND and by SEA an EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE-TO-PEOPLE EXPERIENCE Accompanied by PROFESSOR TIM DUANE

CUBA BY LAND AND BY SEA AN EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE-TO-PEOPLE EXPERIENCE Accompanied by PROFESSOR TIM DUANE UNESCO UNITED STATES Deluxe Small Sailing Ship World Heritage Site FLORIDA Air Routing Miami Cruise Itinerary Land Routing Gulf of Mexico At Viñales Valley lan Havana ti CUBA c O ce Santa Clara an Pinar del Río Cienfuegos Trinidad Caribbean Sea Santiago de Cuba Be among the privileged few to join this uniquely designed people-to-people itinerary, featuring a six-night cruise from Santiago de Cuba along the island’s southern coast followed Itinerary by three nights in the spirited capital city of Havana—an February 3 to 12, 2019 extraordinary opportunity to traverse the entire breadth Santiago de Cuba, Trinidad, Cienfuegos, Santa Clara, of Cuba. Beneath 16,000 square feet of billowing white canvas, sail aboard the exclusively chartered, three-masted Havana, Pinar del Río Le Ponant, featuring only 32 deluxe Staterooms. Enjoy an Day unprecedented people-to-people experience engaging 1 Depart the U.S./Arrive Santiago de Cuba, Cuba/ local Cubans and U.S. travelers to share commonalities Embark Le Ponant and experience firsthand the true character of the Caribbean’s largest and most complex island. In Santiago de 2 Santiago de Cuba Cuba, visit UNESCO World Heritage-designated El Morro. 3 Santiago de Cuba See the UNESCO World Heritage sites of Old Havana, 4 Cruising the Caribbean Sea Cienfuegos, Trinidad and the Viñales Valley. Accompanied by an experienced, English-speaking Cuban host, 5 Trinidad immerse yourself in a comprehensive and intimate travel 6 Cienfuegos for Santa Clara experience that explores the history, culture, art, language, cuisine and rhythms of daily Cuban life while interacting 7 Cienfuegos/Disembark ship/Havana with local Cuban experts including musicians, artists, 8 Havana farmers and academics.