Unmapping Knowledge: Connecting Histories About Haitians in Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

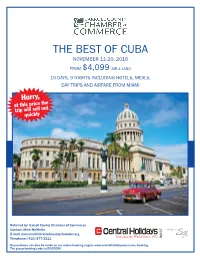

The Best of Cuba

THE BEST OF CUBA NOVEMBER 11-20, 2016 FROM $4,099 AIR & LAND 10 DAYS, 9 NIGHTS INCLUDING HOTELS, MEALS, DAY TRIPS AND AIRFARE FROM MIAMI Hurry, this price the at t trip will sell ou quickly Referred by: Carroll County Chamber of Commerce Contact: Mike McMullin Member of E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (410) 977-3111 Reservations can also be made on our online booking engine www.centralholidayswest.com/booking. The group booking code is: B002054 THE BEST OF CUBA 10 DAYS/9 NIGHTS from $4,099 air & land (1) MIAMI – (3) HAVANA – (3) SANTIAGO DE CUBA – (2) CAMAGUEY FLORIDA 1 Miami Havana 3 Viñales Pinar del Rio 2 CUBA Camaguey Viñales Valley 3 Santiago de Cuba # - NO. OF OVERNIGHT STAYS Day 1 Miami Arrive in Miami and transfer to your airport hotel on your own. This evening in the hotel lobby meet your Central Holidays Representative who will hold a mandatory Cuba orientation meeting where you will receive your final Cuba documentation and meet your traveling companions. TOUR FEATURES Day 2 Miami/Havana This morning, transfer to Miami International Airport •ROUND TRIP AIR TRANSPORTATION - Round trip airfare from – then board your flight for the one-hour trip to Havana. Upon arrival at José Miami Martí International Airport you will be met by your English-speaking Cuban escort and drive through the city where time stands still, stopping at •INTER CITY AIR TRANSPORTATION - Inter City airfare in Cuba Revolution Square to see the famous Che Guevara image with his well-known •FIRST-CLASS ACCOMMODATIONS - 9 nights first class hotels slogan of “Hasta la Victoria Siempre” (Until the Everlasting Victory, Always) (1 night in Miami, 3 nights in Havana, 3 nights in Santiago lives. -

Enduring Ties the Human Connection Between Greater Boston, Latin America and the Caribbean

Enduring Ties The Human Connection Between Greater Boston, Latin America and the Caribbean Prepared for The Building Broader Communities in Americas Working Group by The Philanthropic Initiative and Boston Indicators Greater Boston’s Immigrants and Their Connections to Latin America and the Caribbean | 1 The Boston Foundation The Boston Foundation, Greater Boston’s community foundation, is one of the largest community foundations in the nation, with net assets of some $1 billion. In 2016, the Foundation and its donors paid $100 million in grants to nonprofit organizations and received gifts of more than $107 million. The Foundation is proud to be a partner in philanthropy, with more than 1,000 separate charitable funds established by donors either for the general benefit of the community or for special purposes. The Boston Foundation also serves as a major civic leader, think tank and advocacy organization, commissioning research into the most critical issues of our time and helping to shape public policy designed to advance opportunity for everyone in Greater Boston. The Philanthropic Initiative (TPI), a distinct operating unit of the Foundation, designs and implements customized philanthropic strategies for families, foundations and corporations both here and around the globe. For more information about the Boston Foundation or TPI, visit tbf.org or call 617.338.1700. The Philanthropic Initiative The Philanthropic Initiative (TPI) is a global philanthropic consulting practice that helps individuals, families, foundations, and corporations develop and execute customized strategies to increase the impact of their giving and achieve philanthropy that is more strategic, effective, and fulfilling. For nearly 30 years, TPI has served as consultant and thought partner to ambitious donors and funders who embrace innovative thinking in their efforts to find local, national, and global levers of change. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Culture Haiti

\. / '• ,-') HHHaitiHaaaiiitttiii # l~- ~~- J;,4' ). ~ History ' • The native Taino Amerindians inhabited the island of Hispaniola when discovered by Columbus in 1492 and were virtually annihilated by Spanish settlers within 25 years. • In the early 17th century, the French established a presence on Hispaniola, and in 1697, Spain ceded the western third of the island to the French which later became Haiti. • The French colony, based on forestry and sugar-related industries, became one of the wealthiest in the Caribbean, but only through the heavy importation of African slaves and considerable environmental degradation. • In the late 18th century, Haiti's nearly half million slaves revolted under Toussaint L'Ouverture. After a prolonged struggle, Haiti became the first black republic to declare its independence in 1804. The poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, Haiti has been plagued by political violence for most of its history. • After an armed rebellion led to the departure of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in February 2004, an interim government took office to organize new elections under the auspices of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). Continued violence and technical delays prompted repeated postponements, • Haiti inaugurated a democratically elected president and parliament in May of 2006. • Immigration: Immigrants to the US encounter the problems and difficulties common to many new arrivals, compounded by the fact that the Haitians are "triple minorities": they are foreigners, they speak Haitian Creole that no one else does, and they are black. • Results from Census 2000 show 419,317 foreign-born from Haiti live in the U.S., representing 1.3 percent of the total foreign-born population of 31.1 million and 0.1 percent of the total population of 281.4 million. -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

Engaging the Haitian Diaspora

Engaging the Haitian Diaspora Emigrant Skills and Resources are needed for Serious Growth and development, not Just Charity By Tatiana Wah ver the last five decades, Haiti has lost to the developed and developing world a significant amount of its already meager manpower resources, O largely in the form of international migration. This has led to a significant pool of skilled human capital residing mostly in the Dominican Republic, the United States, and Canada as diaspora communities. Some estimates show that as much as 70 percent of Haiti’s skilled human resources are in the diaspora. Meanwhile, it is increasingly argued that unless developing nations such as Haiti improve their skilled and scientific infrastructures and nurture the appropriate brainpower for the various aspects of the development process, they may never advance beyond their current low socio-economic status. Faced with persistent underdevelopment problems and with language and cultural barriers, international aid agencies, development scholars, and practitioners are increasingly and loudly calling for diaspora engagement programs. The processes required to construct successful diaspora engagement strategies for Haiti’s development, however, are not well understood and consequently merit serious attention. Programs make implicit and explicit assumptions about diaspora members that do not apply to the general understanding of how émigrés build or rebuild their worlds. Programs fail to place strategies within the larger framework of any national spatial-economic development plan or its implementation. Cur- rent engagement strategies treat nationalistic appeals and diaspora consciousness as sufficient to entice members of the diaspora to return or at least to make indi - rect contributions to their homeland. -

Background on Haiti & Haitian Health Culture

A Cultural Competence Primer from Cook Ross Inc. Background on Haiti & Haitian Health Culture History & Population • Concept of Health • Beliefs, Religion & Spirituality • Language & Communication • Family Traditions • Gender Roles • Diet & Nutrition • Health Promotion/Disease Prevention • Illness-Related Issues • Treatment Issues • Labor, Birth & After Care • Death & Dying THIS PRIMER IS BEING SHARED PUBLICLY IN THE HOPE THAT IT WILL PROVIDE INFORMATION THAT WILL POSITIVELY IMPACT 2010 POST-EARTHQUAKE HUMANITARIAN RELIEF EFFORTS IN HAITI. D I S C L A I M E R Although the information contained in www.crcultureVision.com applies generally to groups, it is not intended to infer that these are beliefs and practices of all individuals within the group. This information is intended to be used as a basis for further exploration, not generalizations or stereotyping. C O P Y R I G H T Reproduction or redistribution without giving credit of authorship to Cook Ross Inc. is illegal and is prohibited without the express written permission of Cook Ross Inc. FOR MORE INFORMATION Contact Cook Ross Inc. [email protected] phone: 301-565-4035 website: www.CookRoss.com Background on Haiti & Haitian Health Culture Table of Contents Chapter 1: History & Population 3 Chapter 2: Concept of Health 6 Chapter 3: Beliefs, Religion & Spirituality 9 Chapter 4: Language & Communication 16 Chapter 5: Family Traditions 23 Chapter 6: Gender Roles 29 Chapter 7: Diet & Nutrition 30 Chapter 8: Health Promotion/Disease Prevention 35 Chapter 9: Illness-Related Issues 39 Chapter 10: Treatment Issues 57 Chapter 11: Labor, Birth & After Care 67 Chapter 12: Death & Dying 72 About CultureVision While health care is a universal concept which exists in every cultural group, different cultures vary in the ways in which health and illness are perceived and how care is given. -

Who Is Afro-Latin@? Examining the Social Construction of Race and Négritude in Latin America and the Caribbean

Social Education 81(1), pp 37–42 ©2017 National Council for the Social Studies Teaching and Learning African American History Who is Afro-Latin@? Examining the Social Construction of Race and Négritude in Latin America and the Caribbean Christopher L. Busey and Bárbara C. Cruz By the 1930s the négritude ideological movement, which fostered a pride and conscious- The rejection of négritude is not a ness of African heritage, gained prominence and acceptance among black intellectuals phenomenon unique to the Dominican in Europe, Africa, and the Americas. While embraced by many, some of African Republic, as many Latin American coun- descent rejected the philosophy, despite evident historical and cultural markers. Such tries and their respective social and polit- was the case of Rafael Trujillo, who had assumed power in the Dominican Republic ical institutions grapple with issues of in 1930. Trujillo, a dark-skinned Dominican whose grandmother was Haitian, used race and racism.5 For example, in Mexico, light-colored pancake make-up to appear whiter. He literally had his family history African descended Mexicans are socially rewritten and “whitewashed,” once he took power of the island nation. Beyond efforts isolated and negatively depicted in main- to alter his personal appearance and recast his own history, Trujillo also took extreme stream media, while socio-politically, for measures to erase blackness in Dominican society during his 31 years of dictatorial the first time in the country’s history the rule. On a national level, Trujillo promoted -

CSA HAITI 2016 41St Caribbean Studies Association Conference Day 2 Tuesday, 7 June 2016

CSA HAITI 2016 41st Caribbean Studies Association Conference Day 2 Tuesday, 7 June 2016 www.caribbeanstudiesassociation.org 1 2 TUESDAY MARDI MARTES 3 TUESDAY - 7 June 2016 8:00 AM H. Adlai Murdoch, Tufts University Hegel, Haiti, and the Inscription of Diasporic Blackness Registration and Administrative Matters MARTES Inscription et questions administratives / Irline François, Goucher College Registro y asuntos administrativos Haunting Capital, Legacies and Lifelines Enskripsyon ak administration Regine Michelle Jean-Charles, Boston College Sujets et assujetties : Les femmes esclaves dans Rosalie MARDI 8:00 AM - 8:10 AM l’infâme et Humus / Encuentros / Rasanblaj / Encounters / Rencontres (1) H2 Marriott Kolibri Terrace Opening Session G 8:00 AM – 9:30 AM Exiles and/or Migrants: Representation, Testimony, Marriott Ayizan 1 and Experience Egzile ak/oubyen Imigran: Reprezantasyon, Temwayaj ak Ek- TUESDAY TUESDAY Opening Session 2: Louvri Bayè pou "Migrations of Afro- speryans Caribbean Spirituality" Exilios y/o emigrantes: representación, testimonio y experi- Séance d'ouverture: Louvri Bayè pou "Migrations de la spiritu- encia alité afro-caribéenne" Sesión de apertura 2: Louvri Bayè pou "Migraciones de la espir- Chair: Juliette Storr, Pennsylvania State University itualidad afro-caribeña" Media’s Portrayal of the Haitian Diaspora: Integration or Isola- tion Chair: Patrick Bellegarde-Smith, University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee Oneil Hall, University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus M. Jacqui Alexander, University of Toronto Border restrictions: -

Haitian Diaspora Impact on Haitian Socio-Political and Economic Development

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Haitian Diaspora Impact on Haitian Socio-Political and Economic Development Sharleen Rigueur CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/51 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Haitian Diaspora Impact on Haitian Socio-Political and Economic Development Sharleen Rigueur June 2011 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York Thesis Advisor: Professor Juergen Dedring Abstract.......................................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: Introduction.........................................................................................................6 Topic ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Justification/Rationale ................................................................................................................... 7 Thesis..................................................................................................................................................11 Theoretical -

CUBA by LAND and by SEA an EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE-TO-PEOPLE EXPERIENCE Accompanied by PROFESSOR TIM DUANE

CUBA BY LAND AND BY SEA AN EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE-TO-PEOPLE EXPERIENCE Accompanied by PROFESSOR TIM DUANE UNESCO UNITED STATES Deluxe Small Sailing Ship World Heritage Site FLORIDA Air Routing Miami Cruise Itinerary Land Routing Gulf of Mexico At Viñales Valley lan Havana ti CUBA c O ce Santa Clara an Pinar del Río Cienfuegos Trinidad Caribbean Sea Santiago de Cuba Be among the privileged few to join this uniquely designed people-to-people itinerary, featuring a six-night cruise from Santiago de Cuba along the island’s southern coast followed Itinerary by three nights in the spirited capital city of Havana—an February 3 to 12, 2019 extraordinary opportunity to traverse the entire breadth Santiago de Cuba, Trinidad, Cienfuegos, Santa Clara, of Cuba. Beneath 16,000 square feet of billowing white canvas, sail aboard the exclusively chartered, three-masted Havana, Pinar del Río Le Ponant, featuring only 32 deluxe Staterooms. Enjoy an Day unprecedented people-to-people experience engaging 1 Depart the U.S./Arrive Santiago de Cuba, Cuba/ local Cubans and U.S. travelers to share commonalities Embark Le Ponant and experience firsthand the true character of the Caribbean’s largest and most complex island. In Santiago de 2 Santiago de Cuba Cuba, visit UNESCO World Heritage-designated El Morro. 3 Santiago de Cuba See the UNESCO World Heritage sites of Old Havana, 4 Cruising the Caribbean Sea Cienfuegos, Trinidad and the Viñales Valley. Accompanied by an experienced, English-speaking Cuban host, 5 Trinidad immerse yourself in a comprehensive and intimate travel 6 Cienfuegos for Santa Clara experience that explores the history, culture, art, language, cuisine and rhythms of daily Cuban life while interacting 7 Cienfuegos/Disembark ship/Havana with local Cuban experts including musicians, artists, 8 Havana farmers and academics.