Lucas Cranach's Legacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Storage in Early Modern Art Museums: the Value of Objects

CODART TWINTIG Warsaw, 21-23 May 2017 – Lecture 22 May Storage in Early Modern Art Museums: The Value of Objects Behind the Scenes Dr. Robert Skwirblies, Researcher at the Technical University, Berlin Full text As Martina Griesser stated in 2012, the history of museum storage has still to be written.1 She presumes that this history began in the late 19th century – when appropriate storage rooms were designed and built for the first time. That stands to be proven: actually, the first modern museums, founded in the decades around 1800, did have some structures that can be called storage rooms. In the following minutes, I would like to show you how this question arose in the first place, and how curators reacted to it. Some written sources and plans show us traces of the early storage design. Traces, I say, because we do not know exactly what the first storage rooms looked like. I have not found any details concerning storage rooms in museums in Paris or London. I have found some hints for museums in Italian cities and in Berlin, but no precise plans or technical details. What we can say is: The question of storing works of art in order to protect them from damage, destruction, or deprivation arose often and all over. At the same time, the storage of objects behind the display space was avoided or at least only temporary. In the early history of museums, storage rooms seem to have not been planned as such. Indeed, storing works of art was contrary to the very reason museums were founded: bringing hidden collections and treasures to light, making them visible to a public (which itself was in the state of being formed as the modern society, the citizens) and exhibiting them for the purposes of education, enjoyment, and the objects’ own good. -

The Young Talent in Italy

Originalveröffentlichung in: Jonckheere, Koenraad (Hrsg.): Michiel Coxcie, 1499 - 1592, and the giants of his age : [...on the occasion of the exhibition "Michiel Coxcie: the Flemish Raphael", M - Museum Leuven, 31 October 2013 - 23 February 2014], London 2013, S. 50-63 und 198-204 Eckhard Leuschner THE YOUNG TALENT IN ITALY 4U ichiel Coxcie appears to have been in Italy between about 1530 and a.539.1 With just two exceptions (see below), no contemporary archival documentation relating to this phase of his career has so far been published. Giorgio Vasari mentions that he met Coxcie in Rome in M1532,2 and the surviving paintings, drawings and prints indicate that that is where he spent almost all his time in Italy. As far as the art history of Rome in the Cinquecento is concerned, the 1530s may well be the least studied decade of the century. 3 That is partly due to the political events of the previous years, especially the Sack of Rome in 1527 and its aftermath. When the troops of Emperor Charles V stripped the city of its treasures and political importance, they also weakened the finances of local patrons and the demand for art in general. However, the onset of the Reformation in the North had made itself felt even before then, and the number of works of art commissioned and produced in Rome had been in decline since the early 1520s.4 Although the city ’s artistic life never came to a complete standstill (not even during or immediately after the sack), the scarcity of information on artists active in Rome around 1530 speaks for itself. -

Joseph Accused by Potiphar's Wife

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Rembrandt Workshop Dutch 17th Century Rembrandt van Rijn Dutch, 1606 - 1669 Joseph Accused by Potiphar's Wife 1655 oil on canvas transferred to canvas overall: 105.7 x 97.8 cm (41 5/8 x 38 1/2 in.) framed: 130.8 x 123.2 cm (51 1/2 x 48 1/2 in.) Inscription: lower right: Rembrandt. f.1655. Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.79 ENTRY This painting depicts an episode in the life of Joseph described in the Book of Genesis, chapter 39. Joseph, who had been sold to Potiphar, an officer of the pharaoh, came to be trusted and honored in Potiphar’s household. He was, however, falsely accused by Potiphar’s wife, Iempsar, of trying to violate her, after her attempts at seduction had failed. When he fled from her, she held on to his robe and eventually used it as evidence against him. In this painting Iempsar recounts her tale to Potiphar as she gestures toward Joseph’s red robe draped over the bedpost. While Potiphar listens intently to the story, Joseph, dressed in a long brown tunic and with the keys denoting his household responsibilities hanging from his belt, stands serenely on the far side of the bed. The story of Joseph must have fascinated Rembrandt, for he devoted a large number of drawings, prints, and paintings to the life of this Old Testament figure. Although his primary source of inspiration was undoubtedly the Bible, he also drew upon other literary traditions to amplify his understanding of the biblical text. -

Daxer & M Arschall 20 19 XXVI

XXVI Daxer & Marschall 2019 Recent Acquisitions, Catalogue XXVI, 2019 Barer Strasse 44 | 80799 Munich | Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 | Fax +49 89 28 17 57 | Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] | www.daxermarschall.com 2 Oil Sketches, Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 1668-1917 4 My special thanks go to Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald for their research and their work on the texts. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Peter Axer, Iris Berndt, Robert Bryce, Christine Buley-Uribe, Sue Cubitt, Kilian Heck, Wouter Kloek, Philipp Mansmann, Verena Marschall, Werner Murrer, Otto Naumann, Peter Prange, Dorothea Preys, Eddy Schavemaker, Annegret Schmidt- Philipps, Ines Schwarzer, Gerd Spitzer, Andreas Stolzenburg, Jörg Trempler, Jana Vedra, Vanessa Voigt, Wolf Zech. 6 Our latest catalogue Oil Sketches, Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 2019 Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings, Oil Sketches, comes to you in good time for this year’s TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 2019 erreicht Sie Maastricht. TEFAF is the international art market high point of the year. It runs rechtzeitig vor dem wichtigsten Kunstmarktereignis from March 16-24, 2019. des Jahres, TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair, Maastricht, 16. - 24. März 2019, auf der wir mit Stand The Golden Age of seventeenth-century Dutch painting is well represented in 332 vertreten sind. our 2019 catalogue, with particularly fine works by Jan van Mieris and Jan Steen. -

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

Albrecht Dürer's “Oblong Passion”

ALBRECHT DÜRER’S “OBLONG PASSION”: THE IMPACT OF THE REFORMATION AND NETHERLANDISH ART ON THE ARTIST’S LATE DRAWINGS by DANA E. COWEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2014 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Dana E. Cowen ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Catherine B. Scallen (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Jon L. Seydl ________________________________________________ Holly Witchey ________________________________________________ Erin Benay ________________________________________________ 4 November 2013 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Nancy and John, and to my brother Mark Table of Contents Table of Contents i List of Figures ii Acknowledgements xi Introduction 1 Chapter One 23 Albrecht Dürer in the Netherlands, 1520 to 1521: The Diary and Works of Art Chapter 2 58 Dürer and the Passion: The “Oblong Passion” and its Predecessors Chapter 3 111 Dürer, Luther, and the Reformation: The Meaning of the “Oblong Passion” Chapter 4 160 The “Oblong Passion” Drawings and their Relationship to Netherlandish Art Conclusion 198 Appendix 1: 204 Martin Luther. “Ein Sermon von der Betrachtung des heiligen Leidens Christi” (A Sermon on Meditating on the Holy Passion of Christ), 1519 Appendix 2: 209 The Adoration of the Magi Appendix 3: 219 The Progression of Scholarship on Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish and German Drawings from the Late Nineteenth-Century to the Present Figures 233 Bibliography 372 i List of Figures Fig. -

Studies in the History of Collecting & Art Markets

Art Crossing Borders Studies in the History of Collecting & Art Markets Editor in Chief Christian Huemer (Belvedere Research Center, Vienna) Editorial Board Malcolm Baker (University of California, Riverside) Ursula Frohne (Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster) Daniela Gallo (Université de Lorraine, Nancy) Hans van Miegroet (Duke University, Durham) Inge Reist (The Frick Collection, New York) Adriana Turpin (Institut d’Études Supérieures des Arts, London) Filip Vermeylen (Erasmus University, Rotterdam) VOLUME 6 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hcam Art Crossing Borders The Internationalisation of the Art Market in the Age of Nation States, 1750–1914 Edited by Jan Dirk Baetens Dries Lyna LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Giuseppe de Nittis, The National Gallery, 1877. Oil on canvas, 70 × 105 cm. Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris. © Julien Vidal – Petit Palais – Roger-Viollet The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2019001443 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 2352-0485 ISBN 978-90-04-29198-0 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-29199-7 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by the Editors and Authors. Published by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

3787329536 Lp.Pdf

HEGEL-STUDIEN In Verbindung mit der Hegel-Kommission der Rheinisch-Westfälischen Akademie der Wissenschaften herausgegeben von FRIEDHELM NICOLIN und OTTO PÖGGELER Band 31 FELIX MEINER VERLAG HAMBURG Inhaltlich unveränderter Print-On-Demand-Nachdruck der Originalausgabe von 1996, erschienen im Verlag Bouvier, Bonn. Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über ‹http://portal.dnb.de› abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-7873-1495-9 ISBN eBook: 978-3-7873-2953-3 ISSN 0073-1578 © Felix Meiner Verlag GmbH, Hamburg 2016. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dies gilt auch für Vervielfältigungen, Übertragungen, Mikro- verfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen, soweit es nicht §§ 53 und 54 URG ausdrücklich gestatten. Gesamtherstellung: BoD, Norderstedt. Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Werkdruckpapier, hergestellt aus 100 % chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff. Printed in Germany. www.meiner.de/hegel-studien INHALT ABHANDLUNGEN OTTO PöGGELER (Bochum) Hegels Ästhetik und die Konzeption der Berliner Gemälde- galerie 9 ANDREAS GROSSMANN (Bochum) Weltgeschichtliche Betrachtungen in systematischer Absicht. Zur Gestalt von Hegels Berliner Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte 27 HEINZ EIDAM (Kassel) Die vergessene Zukunft. Anmerkungen zur Hegel-Rezeption in Cieszkowskis „Prolegomena zur Historiosophie" (1838) 63 Lu DE VOS (Löwen) Hegels Enzyklopädie 1827 und 1830: Die Offenheit des Systems? 99 BURKHARD LIEBSCH (Ulm) Probleme einer genealogischen Kritik der Erirmerung. Anmerkungen zu Hegel, Nietzsche und Foucault 113 LITERATURBERICHTE UND KRITIK G. W. F. Hegel: El „Fragmente de Tubinga" (MARIANO ALVAREZ- GOMEZ, Salamanca) 141 Myriam Bienenstock: Politique du jeune Hegel (ELISABETH WEISSER- LOHMANN, Hagen) 143 Bruno Coppieters: Kritik der reinen Empirie (FRANZ HESPE, Bergen) 148 Transzendentalphilosophie und Spekulation. -

Botticelli Past and Present Ever, the Significant and Continued Debate About the Artist

The recent exhibitions dedicated to Botticelli around the world show, more than and Present Botticelli Past ever, the significant and continued debate about the artist. Botticelli Past and Present engages with this debate. The book comprises four thematic parts, spanning four centuries of Botticelli’s artistic fame and reception from the fifteenth century. Each part comprises a number of essays and includes a short introduction which positions them within the wider scholarly literature on Botticelli. The parts are organised chronologically beginning with discussion of the artist and his working practice in his own time, moving onto the progressive rediscovery of his work from the late eighteenth to the turn of the twentieth century, through to his enduring impact on contemporary art and design. Expertly written by researchers and eminent art historians and richly illustrated throughout, the broad range of essays in this book make a valuable contribution to Botticelli studies. Ana Debenedetti is an art historian specialising in Florentine art, artistic literature and workshop practice in the Renaissance. She is Curator of Paintings at the Victoria and Albert Museum, responsible for the collections of paintings, drawings, watercolours and miniatures. She has written and published on Renaissance art and Botticelli philosophy. Caroline Elam is a Senior Research Fellow at the Warburg Institute, University of London. She specialises in architecture, art and patronage in the Italian Renaissance and in the reception of early Italian art in the late nineteenth and twentieth century. Past She has held academic positions at the University of Glasgow, King’s College, Cambridge and Westfield College, University of London. -

La Fotografia Nel Museo D'arte a Fine Ottocento

DONATA LEVI La fotografia nel museo d’arte a fine Ottocento: sovrapposizioni e occasioni per una rinnovata filologia visiva. Alcuni spunti Abstract The article deals with the effects of photography on the practices of art historians, focusing on some German cases. Photography, defined by Paul de Saint-Victor in 1887 as the “musée en action de l’art européen,” offered unprecedented opportunities for a renewed visual philology. Yet this evolution was more complex and less unidirectional than is gener- ally thought. The illustrated publications of Gustav Scheuer in the 1860s attest to different ways of manipulating photographic images and illumi- nate the connections between photography and comparative methods, which initially concerned the relationships between original paintings and photographs much more than those among paintings themselves. Keywords CONNOISSEURSHIP; ART HISTORY; HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY; SECOND HALF OF 19TH CENTURY; MUSEUMS; GERMANY; PHOTOGRAPHIC ALBUM; VISUAL PHILOLOGY; FLORENCE hat photography can be justifiably called one of the founding “T fathers of modern art history” −1 è fatto da sempre dato pacifi- camente per scontato. È indubbio che, pur tenendo conto dei noti limiti tecnici, specialmente per quanto riguarda la resa dei dipinti, nei primi decenni dopo la sua invenzione, le potenzialità del mezzo fu- rono prontamente avvertite dagli esperti. Scriveva già nel 1865 Herman Grimm che pochi anni dopo avrebbe ricoperto la prima cattedra berli- nese di storia dell’arte: — Wer war früher im Stande die Reproduktion eines Gemäldes, alle Skizzen dazu, alle Stiche danach, alle Studien dafür auf demselben 60 Copyright © D. Levi, Università di Udine ([email protected]) · DOI: 10.14601/RSF-12246 Open access article published by Firenze University Press · ISSN: 2421-6429 (print) 2421-6941 (online) · www.fupress.com/rsf Tische ausbreiten und ruhig und unbeirrt vergleichen zu können? Wer war so toll früher, sich dem Gedanken hinzugeben, es sei doch eine schöne Sache, die Reihenfolge aller Werke eines großen Meisters ver- einigt vor sich zu sehn? −2. -

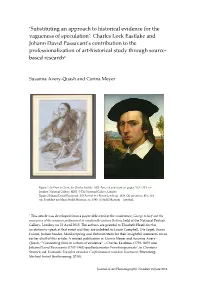

Charles Lock Eastlake and Johann David Passavant’S Contribution to the Professionalization of Art-Historical Study Through Source- Based Research1

‘Substituting an approach to historical evidence for the vagueness of speculation’: Charles Lock Eastlake and Johann David Passavant’s contribution to the professionalization of art-historical study through source- based research1 Susanna Avery-Quash and Corina Meyer Figure 1 Sir Francis Grant, Sir Charles Eastlake, 1853. Pen, ink and wash on paper, 29.3 x 20.3 cm. London: National Gallery, H202. © The National Gallery, London Figure 2 Johann David Passavant, Self-Portrait in a Roman Landscape, 1818. Oil on canvas, 45 x 31.6 cm. Frankfurt am Main: Städel Museum, no. 1585. © Städel Museum – Artothek 1 This article was developed from a paper delivered at the conference, George Scharf and the emergence of the museum professional in nineteenth-century Britain, held at the National Portrait Gallery, London, on 21 April 2015. The authors are grateful to Elizabeth Heath for the invitation to speak at that event and they are indebted to Lorne Campbell, Ute Engel, Susan Foister, Jochen Sander, Marika Spring and Deborah Stein for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article. A related publication is: Corina Meyer and Susanna Avery- Quash, ‘“Connecting links in a chain of evidence” – Charles Eastlakes (1793-1865) und Johann David Passavants (1787-1861) quellenbasierter Forschungsansatz’, in Christina Strunck, ed, Kulturelle Transfers zwischen Großbritannien und dem Kontinent, Petersberg: Michael Imhof (forthcoming, 2018). Journal of Art Historiography Number 18 June 2018 Avery-Quash and Meyer ‘Substituting an approach to historical evidence for the vagueness of speculation’ ... Introduction After Sir Charles Eastlake (1793-1865; Fig. 1) was appointed first director of the National Gallery in 1855, he spent the next decade radically transforming the institution from being a treasure house of acknowledged masterpieces into a survey collection which could tell the story of the development of western European painting. -

Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich- Feather Fan C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Rembrandt van Rijn Dutch, 1606 - 1669 Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich- Feather Fan c. 1656/1658 oil on canvas transferred to canvas overall: 99.5 × 83 cm (39 3/16 × 32 11/16 in.) framed: 132.08 × 115.25 × 13.97 cm (52 × 45 3/8 × 5 1/2 in.) Widener Collection 1942.9.68 ENTRY The early history of Portrait of a Gentleman with a Tall Hat and Gloves [fig. 1] and Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-Feather Fan is shrouded in mystery, although it seems likely that they were the pair of portraits by Rembrandt listed in the Gerard Hoet sale in The Hague in 1760. [1] They had entered the Yusupov collection by 1803, when the German traveler Heinrich von Reimers saw them during his visit to the family’s palace in Saint Petersburg, then located on the Fontanka River. [2] Prince Nicolai Borisovich Yusupov (1751–1831) acquired the core of this collection on three extended trips to Europe during the late eighteenth century. In 1827 he commissioned an unpublished five-volume catalog of the paintings, sculptures, and other treasures (still in the family archives at the Arkhangelskoye State Museum & Estate outside Moscow) that included a description as well as a pen-and-ink sketch of each object. The portraits hung in the “Salon des Antiques.” His only son and heir, Prince Boris Nicolaievich Yusupov (1794–1849), published a catalog of the collection in French in 1839.