Faculty of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

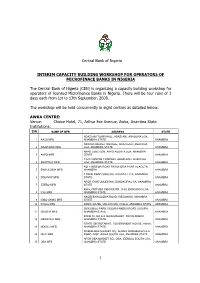

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

History of Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Igboland (1923 – 2010 )

NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010 ) FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION Digitally Signed by : Content manager’s Name Fred Attah DN : CN = Webmaster’s name O= University of Nigeri a, Nsukka OU = Innovation Centre 1 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AND CULTURAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) DEGREE IN RELIGION BY NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 SUPERVISOR: REV. FR. PROF. H. C. ACHUNIKE 2014 Approval Page 2 This thesis has been approved for the Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka By --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Rev. Fr. Prof. H. C. Achunike Date Supervisor -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ External Examiner Date Prof Musa Gaiya --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof C.O.T. Ugwu -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof Agha U. Agha -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Head of Department Date Rev. Fr. Prof H.C. Achunike --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Dean of Faculty Date Prof I.A. Madu Certification 3 We certify that this thesis -

SIGNIFICANCE of ANIMAL MOTIFS in INDIGENOUS ULI BODY and WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied A

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol. 8, No. 1. June 2019 SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS… Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied Arts Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. [email protected] This article explores the significance of animal motifs in traditional Uli body and wall paintings. A critical assessment and understanding of the philosophical import of animals in African concept of existence is vital for an in-depth appreciation of their (animals’) symbols in indigenous African artworks. This paper attempts to a draw parallel between traditional beliefs concerning certain animals among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria and motifs derived from indigenous Uli body and wall painting. In essence, the article sees animal motifs in Uli body and wall paintings as playing an aesthetic as well as metaphysical roles. Hence I argue that local nuances of religiosity and spirituality have historically imbued the animals with a heightened sense of sacredness in some Igbo communities thus allowing the animals to occupy a mystical space in Igbo cosmology. Introduction The pre-colonial system of knowledge transmission in Africa was not only through oral literature but also through the varied artistic traditions that survived from one generation to the other. The rich heritage of ancient Egyptian arts (including the hieroglyphs), the numerous Neolithic rock paintings and engravings found in Northern Africa, which dates back to 5000 and 2000 BCE respectively were mainly symbolic of vital occurrences of the past, documented through art (Getlein 2002: 335). -

Okanga Royal Drum: the Dance for the Prestige and Initiates Projecting Igbo Traditional Religion Through Ovala Festival in Aguleri Cosmolgy

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.8, No. 3, pp.19-49, March 2020 Published by ECRTD-UK Print ISSN: 2052-6350(Print), Online ISSN: 2052-6369(Online) OKANGA ROYAL DRUM: THE DANCE FOR THE PRESTIGE AND INITIATES PROJECTING IGBO TRADITIONAL RELIGION THROUGH OVALA FESTIVAL IN AGULERI COSMOLGY Madukasi Francis Chuks, PhD ChukwuemekaOdumegwuOjukwu University, Department of Religion & Society. Igbariam Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria. PMB 6059 General Post Office Awka. Anambra State, Nigeria. Phone Number: +2348035157541. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: No literature I have found has discussed the Okanga royal drum and its elements of an ensemble. Elaborate designs and complex compositional ritual functions of the traditional drum are much encountered in the ritual dance culture of the Aguleri people of Igbo origin of South-eastern Nigeria. This paper explores a unique type of drum with mystifying ritual dance in Omambala river basin of the Igbo—its compositional features and specialized indigenous style of dancing. Oral tradition has it that the Okanga drum and its style of dance in which it figures originated in Aguleri – “a farming/fishing Igbo community on Omambala River basin of South- Eastern Nigeria” (Nzewi, 2000:25). It was Eze Akwuba Idigo [Ogalagidi 1] who established the Okanga royal band and popularized the Ovala festival in Igbo land equally. Today, due to that syndrome and philosophy of what I can describe as ‘Igbo Enwe Eze’—Igbo does not have a King, many Igbo traditional rulers attend Aguleri Ovala festival to learn how to organize one in their various communities. The ritual festival of Ovala where the Okanga royal drum features most prominently is a commemoration of ancestor festival which symbolizes kingship and acts as a spiritual conduit that binds or compensates the communities that constitutes Eri kingdom through the mediation for the loss of their contact with their ancestral home and with the built/support in religious rituals and cultural security of their extended brotherhood. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

UNIVERSITY of IBADAN LIBRARY F~Fiva23ia Mige'tia: Abe Ky • by G.D

- / L. L '* I L I Nigerla- magazine - # -\ I* .. L I r~.ifr F No. 136 .,- e, .0981 W1.50r .I :4 UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY F~fiva23ia Mige'tia: ABe ky • By G.D. EKPENYONG (MRS) HIS BIBLIOGRAPHY IS COMING OUT AT A TIME TRADITIONAL RULERS ENCOURAGED THEIR PEOPLE TO AC- T WHEN THERE IS GENERAL OR NATIONAL AWARENESS CEPT ISLAM AND AS A CONSEQUENCE ACCEPT IT AND FOR THE REVIVAL OF OUR CULTURAL HERITage. It IS HOPED CELEBRATED FESTIVALS ASSOCIATED WITH THIS religion. THAT NIGERIANS AND ALIENS RESIDENT IN NigeRIa, FESTIVALS ARE PERIODIC RECURRING DAYS OR SEA- RESEARCHERS IN AFRICAN StudiES, WOULD FIND THIS SONS OF GAIETY OR MERRy-maKING SET ASIDE BY A PUBLICATION A GUIDE TO A BETTER KNOWLEDGE OF THE COMMUNITY, TRIBE OR CLAN, FOR THE OBSERVANCE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE AND DIVERSITY OF THE PEOPLES OF SACRED CELEBRATIOns, RELIGIOUS SOLEMNITIES OR MUs- NIGERIA. ICAL AND TRADITIONAL PERFORMANCE OF SPECIAL SIG- IT IS NECESSARY TO EMPHASISe, HOWEVER, THAT NIFICANCE. It IS AN OCCASION OF PUBLIC MANIFesta- ALTHOUGH THIS IS A PIONEERING EFFORT TO RECORD ALL TION OF JOY OR THE CELEBRATION OF A HISTORICAL OC- THE KNOWN AND UNKNOWN TRADITIONAL FESTIVALS CURRENCE LIKE THE CONQUEST OF A NEIGHBOURING HELD ANNUALLY OR IN SOME CASES, AFTER A LONG VILLAGE IN WAR. IT CAN TAKE THE FORM OF A RELIGIOUS INTERVAL OF TIMe, THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY IS BY NO MEANS CELEBRATION DURING WHICH SACRIFICES ARE OFFERED TO EXHAUSTIVE. THE DIFFERENT GODS HAVING POWER OVER RAIN, Sun- SHINE, MARRIAGE AND GOOD HARVEST. Introduction He IS THE MOST ANCIENT OF ALL YORUBA TOWNS AND NigerIa, ONE OF THE LARGEST COUNTRIES IN AFRIca, IS REGARDED BY ALL YORUBAS AS THE FIRST CITY FROM IS RICH IN CULTURE AND TRADITIOn. -

The Influence of the Supernatural in Elechi Amadi’S the Concubine and the Great Ponds

THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG/MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. SUPERVISOR: DR. EZUGU M.A A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M.A) IN ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 i TITLE PAGE THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG /MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 ii CERTIFICATION This research work has been read and approved BY ________________________ ________________________ DR. M.A. EZUGU SIGNATURE & DATE SUPERVISOR ________________________ ________________________ PROF. D.U.OPATA SIGNATURE & DATE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT ________________________ ________________________ EXTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE & DATE iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my dear son Davids Smile for being with me all through the period of this study. To my beloved husband, Mr Smile Iwejua for his love, support and understanding. To my parents, Elder & Mrs S.C Ekpendu, for always being there for me. And finally to God, for his mercies. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks go to the Almighty God for his steadfast love and for bringing me thus far in my academics. To him be all the glory. My Supervisor, Dr Mike A. Ezugu who patiently taught, read and supervised this research work, your well of blessings will never run dry. My ever smiling husband, Mr Smile Iwejua, your smile and support took me a long way. -

Saharan Africa: the Igbo Paradigm

Journal of International Education and Leadership Volume 5 Issue 1 Spring 2015 http://www.jielusa.org/ ISSN: 2161-7252 The Re-Birth of African Moral Traditions as Key to the Development of Sub- Saharan Africa: The Igbo Paradigm Chika J. B. Gabriel Okpalike Nnamdi Azikiwe University This work is set against the backdrop of the Sub-Saharan African environment observed to be morally degenerative. It judges that the level of decadence in the continent that could even amount to depravity could be blamed upon the disconnect between the present-day African and a moral tradition that has been swept under the carpet through history; this tradition being grounded upon a world view. World-view lies at the basis of the interpretation and operation of the world. It is the foundation of culture, religion, philosophy, morality and so forth; an attempt of humans to impose an order in which the human society works.1 Most times when the African world-view is discussed, the Africa often thought of and represented is the Africa as before in which it is very likely to see religion and community feature as two basic characters of Africa from which morality can be sifted. In his popular work Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe had above all things shown that this old Africa has been replaced by a new breed and things cannot be the same again. In the first instance, the former African communalism in which the community was the primary beneficiary of individual wealth has been wrestled down by capitalism in which the individual is defined by the extent in which he accumulates surplus value. -

A Socio- Economic History of Alcohol in Southeastern Nigeria Since 1890

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background to the Study Alcohol has various socio-economic and cultural functions among the people of southeastern Nigeria. It is used in rituals, marriages, oath taking, festivals and entertainment. It is presented as a mark of respect and dignity. The basic alcoholic beverage produced and consumed in the area was palm -wine tapped from the oil palm tree or from the raffia- palm. Korieh notes that, from the fifteenth century contacts between the Europeans and peoples of eastern Nigeria especially during the Atlantic slave trade era, brought new varieties of alcoholic beverages primarily, gin and whisky.1 Thus, beginning from this period, gins especially schnapps from Holland became integrated in local culture of the peoples of Eastern Nigeria and even assumed ritual position.2 From the 1880s, alcohol became accepted as a medium of exchange for goods and services and a store of wealth.3 By the early twentieth century, alcohol played a major role in the Nigerian economy as one third of Nigeria‘s income was derived from import duties on liquor.4 Nevertheless, prior to the contact of the people of Southern Nigeria with the Europeans, alcohol was derived mainly from the oil palm and raffia palm trees which were numerous in the area. These palms were tapped and the sap collected and drunk at various occasions. From the era of the Trans- Atlantic slave trade, the import of gin, rum and whisky became prevalent.These were used in ex-change for slaves and to pay comey – a type of gratification to the chiefs. Even with the rise of legitimate trade in the 19th century alcoholic beverages of various sorts continued to play important roles in international trade.5 Centuries of importation of gin into the area led to the entrenchment of imported gin in the culture of the people. -

A CRITICAL EVALUATION Justine John Dyikuk Department of M

Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development Vol. 2 No 3, 2019 . ISSN: 2630-7073(Online) 2640-7065(Print) THE INTERSECTION OF COMMUNICATION IN IGWEBUIKE AND TRADO-RURAL MEDIA: A CRITICAL EVALUATION Justine John Dyikuk Department of Mass Communication, Faculty of Arts, University of Jos, Nigeria. [email protected] Abstract Before the coming of the colonialists to Africa, Africans had their organised system of communication known as trado-rural media which was anchored on oramedia. This enabled the people to communicate with each other and transmit vital information within the community. Based on this, the researcher embarked on a study titled: “The Intersection of Communication in Igwebuike and Trado-Rural Media: A Critical Evaluation.” Using the qualitative method of study to ascertain the matter, the study discovered that active listening, complementarity and shared values constituted folk media in rural Africa. It also found that directives, news and advertising as well as idiophones, membranophones and aerophones constitute the content and forms of Igwebuike communication in Igbo culture. The study recommended restoring group communication, upholding cultural heritage and media literacy as panacea. It concluded that the intersection of Igwebuike-communication and trado-rural media are crucial for effective communication beyond the Igbo Nation. Keywords: Communication, Igwebuike, Media, Nigeria, Trado-rural. Introduction Experts have held that before the coming of Colonial Imperialists on the shores of Africa, Africans had their own organised way of communication which is referred to as African Traditional Communication (Nwanne, 2006 cited in Nsereka, 2013) or trado-rural media. These communication systems which are often built on oramedia enabled the people to communicate with each other and also transmit vital information within the community. -

Acculturation and Traditional Mortuary Rites of the Nawfia of Southeastern Nigeria Ugochukwu T. Ugwu

Acculturation and Traditional Mortuary Rites of the Nawfia of Southeastern Nigeria Ugochukwu T. Ugwu http://dx.doi./org/10.4314/ujah.v22i1.1 Abstract This ethnography explores the traditional mortuary rites of the Nawfia, an Igbo group of Southeast Nigeria, aiming to understand the mortuary rites of the Nawfia, how and why it has changed and the factors responsible for the changes. The main data collection strategy was participant observation that began in April 2014. It was supplemented with in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The study found Christianity as a major acculturative factor that has altered almost all the facets of the traditional mortuary rites of the Nawfia Igbo. Furthermore, mortuary rites do not only reinforce social solidarity among the Nawfia Igbo people but also according to what the Nawfia people believe, enable the deceased to attain his rightful position in the spirit world. Keywords: traditional mortuary rites, mortuary rites, southeast Nigeria, Igbo people, acculturation Introduction Mortuary rites have been extensively researched across the world, Africa and the Igbo in particular. These studies were initiated by colonial anthropologists, who hurriedly, for purposes of administration, tried to document what they met on ground, and for easier understanding of how mortuary rites reinforce social solidarity or religious efficacy. Among these were sometimes untrained ethnographers that studied these rites from an ethnocentric Ugwu: Acculturation and Traditional Mortuary Rites of the Nawfia… perspective. For instance, without trying to understand these rites relative to the context and the complex Igbo societies, Basden (1983) concluded his account on mortuary protocols as representing the general Igbo funeral rites, albeit, with ethnocentric disgust. -

(Igbo) Philosophy of Death

Philosophy Study, June 2019, Vol. 9, No. 6, 362-366 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2019.06.006 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Epistemic Inquiry into African (Igbo) Philosophy of Death Raphael Olisa Maduabuchi, Stephen Chijioke Chukwujekwu Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria This paper sought to examine Igbo philosophy of death as an essential feature for authentic human existence in Africa. Death is a mystery which defies human understanding. No wonder, existentialist philosophers conceive death as the facticity of human existence. Different cultures have undertaken to unravel the mystery of death. Hence, African nay Igbo conceives death as a transition of human beings from this physical world of the living to the world of the spirit. The invisible world of the spirit is a place where our revered ancestors live. The second burial rites are performed to gravitate the dead to ancestral world of spirit. African metaphysical assumptions of death and life after death are therefore subjected to critical examination. Keywords: Igbo, Africans, ancestors, spiritual, physical and existence Introduction Death is a common phenomenon which everybody expects in anticipation. Scholars conceive death differently. On this note, death is defined as end of life; the state of being dead (Hornby, 2011, p. 298). The state of being dead implies that one is no longer alive. Death can be sudden, violent and peaceful. In some cases, it comes at a moment when one least expects it. Anybody can die at any moment. Philosophers have undertaken to unravel the mystery behind death. Jean Paul Sartre conceived death as a meaningless absurdity which removes all meaning from human existence (Omoregbe, 1991, p.