Stephan G. Schmid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeffrey Eli Pearson

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4dx9g1rj Author Pearson, Jeffrey Eli Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture By Jeffrey Eli Pearson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Erich Gruen, Chair Chris Hallett Andrew Stewart Benjamin Porter Spring 2011 Abstract Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture by Jeffrey Eli Pearson Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Erich Gruen, Chair The Nabataeans, best known today for the spectacular remains of their capital at Petra in southern Jordan, continue to defy easy characterization. Since they lack a surviving narrative history of their own, in approaching the Nabataeans one necessarily relies heavily upon the commentaries of outside observers, such as the Greeks, Romans, and Jews, as well as upon comparisons of Nabataean material culture with Classical and Near Eastern models. These approaches have elucidated much about this -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

State Party Report

Ministry of Culture Directorate General of Antiquities & Museums STATE PARTY REPORT On The State of Conservation of The Syrian Cultural Heritage Sites (Syrian Arab Republic) For Submission By 1 February 2018 1 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. Damascus old city 5 Statement of Significant 5 Threats 6 Measures Taken 8 2. Bosra old city 12 Statement of Significant 12 Threats 12 3. Palmyra 13 Statement of Significant 13 Threats 13 Measures Taken 13 4. Aleppo old city 15 Statement of Significant 15 Threats 15 Measures Taken 15 5. Crac des Cchevaliers & Qal’at Salah 19 el-din Statement of Significant 19 Measure Taken 19 6. Ancient Villages in North of Syria 22 Statement of Significant 22 Threats 22 Measure Taken 22 4 INTRODUCTION This Progress Report on the State of Conservation of the Syrian World Heritage properties is: Responds to the World Heritage on the 41 Session of the UNESCO Committee organized in Krakow, Poland from 2 to 12 July 2017. Provides update to the December 2017 State of Conservation report. Prepared in to be present on the previous World Heritage Committee meeting 42e session 2018. Information Sources This report represents a collation of available information as of 31 December 2017, and is based on available information from the DGAM braches around Syria, taking inconsideration that with ground access in some cities in Syria extremely limited for antiquities experts, extent of the damage cannot be assessment right now such as (Ancient Villages in North of Syria and Bosra). 5 Name of World Heritage property: ANCIENT CITY OF DAMASCUS Date of inscription on World Heritage List: 26/10/1979 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANTS Founded in the 3rd millennium B.C., Damascus was an important cultural and commercial center, by virtue of its geographical position at the crossroads of the orient and the occident, between Africa and Asia. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

An Artistic, Mythological and Documentary Study of the Atargatis Panel from Et-Tannur, Jordan

Acta Ant. Hung. 57, 2017, 515–534 DOI: 10.1556/068.2017.57.4.10 EYAD ALMASRI – FADI BALAAWI – YAHYA ALSHAWABKEH AN ARTISTIC, MYTHOLOGICAL AND DOCUMENTARY STUDY OF THE ATARGATIS PANEL FROM ET-TANNUR, JORDAN Summary: In 1937 and 1938, a group of high-relief and round statues were uncovered during the joint expedition of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem and the Department of Antiquities in Palestine at the Khirbet et-Tannur Temple, located in Jordan. This expedition was headed by Nelson Glueck (Figs 1, 2). The statues uncovered are important in that they offer considerable information about Nabataean art and religion. This paper concentrates on one of the high-relief statues, called the Atargatis Panel by its excavator, Glueck. It was chosen as a case study for its availability in Amman, Jordan. The other Atargatis statues found at the site are now in the Cincinnati Art Museum in the United States of America. This paper also examines the Nabataean religious beliefs concerning Atargatis and her fertil- ity cult, in addition to the art style of the statue. Furthermore, the digital 3D imaging documentation of the Atargatis statue at The Jordan Museum is presented. Dense image matching algorithms presented a flexible, cost-effective approach for this important work. These images not only provide geometric in- formation but also show the surface textures of the depicted objects. This is especially important for the production of virtual 3D models used as a tool for documentary, educational and promotional purposes. Key words: art history, Nabataean sculpture, Khirbet et-Tannur, Atargatis, documentation, 3D imaging, conservation 1. -

Roman Trade with the Far East: Evidence for Nabataean Middlemen in Puteoli

CHAPTER 5 Roman Trade with the Far East: Evidence for Nabataean Middlemen in Puteoli Taco Terpstra Puteoli, a major Italian harbour town serving Rome, was an important port for trade with the East. It was a hub for the Alexandrian grain fleet, but high-value goods such as Tyrian purple dye must have arrived there too.1 The town prob- ably also saw the movement of luxury products from distant lands outside the empire: spices, silk, and frankincense from Arabia, China, and India. While Puteoli has not yielded archaeological evidence for eastern trade of the rare kind unearthed in Pompeii (where an Indian ivory statuette repre- senting a voluptuous nude female figure was found), epigraphic evidence does exist.2 A small but significant body of inscriptions from the Greek world and from Italy shows Nabataean activity in the Mediterranean. In this paper I will investigate this activity, concentrating most of all on Puteoli, the site where more than half of the known epigraphic evidence was discovered. I will argue, first, that Puteoli housed the only permanent Nabataean community in the Mediterranean and, second, that this community established a mercantile connection between the Nabataeans and their Roman buyers, securing a flow of information and establishing mutual trust for purposes of trade. The Nabataean Kingdom, located about halfway between the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean, was well positioned to play a major role in East–West exchange. The heyday of its commercial activity seems to have been from roughly the mid second century bce to the late first century ce—the time from its rise as a regional power to the time just preceding its annexation by Rome in 106 ce.3 From the silence in the historic record it would seem that with the Roman takeover, the Nabataeans ‘softly and suddenly vanished away’. -

The Mints of Roman Arabia and Mesopotamia Author(S): G

The Mints of Roman Arabia and Mesopotamia Author(s): G. F. Hill Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 6 (1916), pp. 135-169 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/296269 . Accessed: 08/05/2014 18:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Roman Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 18:07:37 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PLATE Xl I f .1 - I ! | i I ; . ' N : i , I I ,S, l I 1 3 11 . 1 . .s . | 11 . _ I . 13 I .1 | I S , I . , I .6 I , 11 | . | , 1 11,1 I _l r : __ OOINS OF ROMAN This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 18:07:37 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions J i V1 (t9X6). I I fi s I B! I R i * . -

The Cult of Dushara and the Roman Annexation of Nabataea the Cult of Dushara and the Roman Annexation of Nabataea

THE CULT OF DUSHARA AND THE ROMAN ANNEXATION OF NABATAEA THE CULT OF DUSHARA AND THE ROMAN ANNEXATION OF NABATAEA By STEPHANIE BOWERS PETERSON, B.A. (Hons.) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Stephanie Bowers Peterson, August 2006 11 MASTER OF ARTS (2006) McMaster University (Classics) Hamilton, Ontari 0 Title: The Cult of Dushara and the Roman Annexation ofNabataea Author: Stephanie Bowers Peterson, B.A (Hons. History, North Carolina State University,2004) Supervisor: Dr. Alexandra Retzleff Number of Pages: viii, 172 111 ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to examine the cult of Dushara, the head of the Nabataean pantheon, in the Nabataean and Roman periods, in order to better understand Nabataean cultural identity following the Roman annexation of Nabataea by Trajan in AD 106. I explore Dushara's cult during the Nabataean and Roman periods by analyzing literary, archaeological, and artistic evidence. An important aspect ofDushara's worship is his close connection with the Nabataean king as lithe god of our lord (the king)" in inscriptions. A major question for this thesis is how Dushara's worship survived in the Roman period after the fall of the Nabataean king. Greco-Roman, Byzantine, and Semitic sources attest to the worship of Dushara in the post-Nabataean period, but these sources are often vague and sometimes present misinterpretations. Therefore, we must necessarily look to archaeological and artistic evidence to present a more complete picture of Dushara's worship in the Roman period. -

Al-Hijr Archaeological Site (Mâdain Sâlih)

AL-HIJR ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE (MÂDAIN SÂLIH) NOMINATION DOCUMENT FOR THE INSCRIPTION ON THE UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE LIST KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA AL-HIJR ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE (MÂDAIN SÂLIH) NOMINATION DOCUMENT FOR THE INSCRIPTION ON THE UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE LIST JANUARY 2007 AL-HIJR ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE (MADÂIN SÂLIH) Table of Contents CONTENTS PRESENTATION p. 8 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROPERTY p. 9 1. a Country (and State Party of Different) p. 10 1. b State, Province or Region p. 11 1. c Name of Property p. 12 1. d Geographical Coordinates to the Nearest Second p. 12 1. e Maps and Plans, Showing the Boundaries of the Nominated Property and BufFer Zone p. 12 1. f Area of the Nominated Property (ha) and Proposed Buffer Zone (ha) p. 17 2. DESCRIPTION p. 18 2. a Description of Property p. 19 2. b History and Development p. 33 3. JUSTIFICATION FOR INSCRIPTION p. 38 3. a Criteria under which Inscription is Proposed (and justification for inscription under these criteria) p. 39 3. b Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value p. 40 3. c Comparative Analysis (including state of conservation of similar properties) p. 42 3. d Integrity and/or Authenticity p. 47 Cover page: Madâin Sâlih, Qasr al-Farîd and the site landscape, G. Ferrandis for MSAP, 2003; KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA 3 AL-HIJR ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE (MADÂIN SÂLIH) Table of Contents 4. STATE OF CONSERVATION AND FACTORS AFFECTING THE PROPERTY p. 50 4. a Present State of Conservation p. 51 4. b Factors Affecting the Property p. 54 (i) Development Pressures (e.g. -

ACOR Newsletter Vol. 27.1

Volume 27.1 Summer 2015 �e Nabataean, Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic Site of Humayma: A Look Back on �ree Decades of Research John P. Oleson, M. Barbara Reeves, and Rebecca M. Foote Most motorists on their way to Wadi Ramm or Aqaba zoom by the unassuming turnoff to Humayma on the Desert Highway, unaware that Humayma is among Jordan’s most interesting and informative archaeological sites. Humayma is located in the northwest corner of the Hisma Desert approximately 80 km south of Petra and 80 km north of Aqaba. Today it can be reached by a 20-minute car or bus excursion offtheDesertHighway.Inancienttimes, the site was located on the ancient King’s Highway, rebuilt in the early 2nd century a.d. as the Via Nova Traiana. Aerial photo of Humayma looking north (photo by Jane Taylor); all images courtesy of the Humayma Excavation Project unless otherwise noted Since the 1980s, several teams of archaeologists have focused �eNabataeanthroughUmayyadse�lementsareconcentrated on Humayma’s ancient remains, each from a slightly differentpoint in a one kilometer square area on the desert plain bordered on the of view. Prehistoric sites on the surrounding jebels were studied by west and northwest by sandstone hills and ridges which were also Donald Henry’s team in the early 1980s, leading to the discovery used for human activities. From the 1st century b.c. until the mid-8th of many tool sca�ers and a new “Qalkhan assemblage.” century a.d., Humayma (in Nabataean, Hawara; in Greek, Auara; �e Nabataean through early Islamic se�lement on the plain in Latin, Hauarra; in Arabic, al-Humayma) was a bustling desert was �rstprobedbyJohnEadie,DavidGraf,andJohnP.Olesonin trading post, military strongpoint, and caravan waystation. -

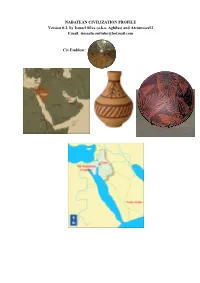

NABATEAN CIVILIZATION PROFILE Version 0.2, by Ismael Silva (A.K.A

NABATEAN CIVILIZATION PROFILE Version 0.2, by Ismael Silva (a.k.a. Aghilas) and Atenmeses52 Email: [email protected] Civ Emblem: • Historical Period: Although the Nabataeans were literate, they left no lengthy historical texts. However, there are thousands of inscriptions still found today in several places where they once lived; including graffiti and on their minted coins. The first historical reference to the Nabataeans is by Greek historian Diodorus Siculus who lived around 30 BC, but he includes some 300 years earlier information about them. • The Twelve Sons of Ishmael: Nebaioth, Qedar, Adbeel, Mibsam, Mishma, Dumah, Massa, Hadad, Tema, Jetur, Naphish, Kedemah. • Civilization Overview: The Nabataeans, also Nabateans, were an Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the Southern Levant, and whose settlements, most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu, now called Petra, in AD 37 – c. 100, gave the name of Nabatene to the borderland between Arabia and Syria, from the Euphrates to the Red Sea. Their loosely controlled trading network, which centered on strings of oases that they controlled, where agriculture was intensively practiced in limited areas, and on the routes that linked them, had no securely defined boundaries in the surrounding desert.Trajan conquered the Nabataean kingdom, annexing it to the Roman Empire, where their individual culture, easily identified by their characteristic finely potted painted ceramics, became dispersed in the general Greco-Roman culture and was eventually lost. They were later converted to Christianity. Jane Taylor, a writer, describes them as "one of the most gifted peoples of the ancient world". • Notes on Warfare: Hence we come to a lightly armoured but swift-moving force which was used for raiding or fighting off raiders.