Instituteof Hydrology, UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

Governmentgazette

ste, ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. LXXI, No. 52 20th AUGUST,1993 Price 2,50 General Notice 499 of 1993. By: ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER262} (a) Deletion of stages Mvuma - Chatsworth and substitution of Matizha. Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits (b) Alteration of route kilometres. IN terms of subsection (4) of section 7 of the Road Motor The service operates as follows— @tansportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that the (a) depart HarareTuesday, Thursday andSaturday 8 a.m., arrive f upplicationsdetailed in the Schedule,forthe issue or amendment of Magombedzi 1.30 p.m.; . toad service permits, have been received for the consideration ofthe ‘Controller of Road Motor Transportation. (b) depart Harare Sunday 1.30p.m., arrive Magombedzi 7.30 p.m.; Anyperson wishingto object to any such application mustlodge with the Controller of Road Motor Transportation, P.O. Box 8332, (c) depart Magombedzi Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Sun- Causeway— day 6 a.m., arrive Harare 1. p.m. — (a) anotice, in writing, ofhis intention to object, so as to reach The service to operate as follows— the Controller’s office not later than the 10th September, 1993; (a) depart Harare Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday 8 a.m., arrive Magombedzi 12 noon; (b) his objection and the groundstherefor, on form R.M.T.24, together withtwocopies thereof, so as toreach the Controller's (bd)-pen Harare Sunday 12.30 p.m., arrive Magombedzi office not later than the Ist October, 1993. 30 p.m.; Any person objecting to an application forthe issue oramendment (c) depart Magombed2i Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Sun. -

Gonarezhou National Park (GNP) and the Indigenous Communities of South East Zimbabwe, 1934-2008

Living on the fringes of a protected area: Gonarezhou National Park (GNP) and the indigenous communities of South East Zimbabwe, 1934-2008 by Baxter Tavuyanago A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR A. S. MLAMBO July 2016 i © University of Pretoria Abstract This study examines the responses of communities of south-eastern Zimbabwe to their eviction from the Gonarezhou National Park (GNP) and their forced settlement in the peripheral areas of the park. The thesis establishes that prior to their eviction, the people had created a utilitarian relationship with their fauna and flora which allowed responsible reaping of the forest’s products. It reveals that the introduction of a people-out conservation mantra forced the affected communities to become poachers, to emigrate from south-eastern Zimbabwe in large numbers to South Africa for greener pastures and, to fervently join militant politics of the 1960s and 1970s. These forms of protests put them at loggerheads with the colonial government. The study reveals that the independence government’s position on the inviolability of the country’s parks put the people and state on yet another level of confrontation as the communities had anticipated the restitution of their ancestral lands. The new government’s attempt to buy their favours by engaging them in a joint wildlife management project called CAMPFIRE only slightly relieved the pain. The land reform programme of the early 2000s, again, enabled them to recover a small part of their old Gonarezhou homeland. -

An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWC Theses and Dissertations AN AGRARIAN HISTORY OF THE MWENEZI DISTRICT, ZIMBABWE, 1980-2004 KUDAKWASHE MANGANGA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.PHIL IN LAND AND AGRARIAN STUDIES IN THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT, UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE November 2007 DR. ALLISON GOEBEL (QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY, CANADA) DR. FRANK MATOSE (PLAAS, UWC) ii ABSTRACT An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004 Kudakwashe Manganga M. PHIL Thesis, Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies, Department of Government, University of the Western Cape. The thesis examines continuity and change in the agrarian history of the Mwenezi district, southern Zimbabwe since 1980. It analyses agrarian reforms, agrarian practices and development initiatives in the district and situates them in the localised livelihood strategies of different people within Dinhe Communal Area and Mangondi Resettlement Area in lieu of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) since 2000. The thesis also examines the livelihood opportunities and challenges presented by the FTLRP to the inhabitants of Mwenezi. Land reform can be an opportunity that can help communities in drought prone districts like Mwenezi to attain food security and reduce dependence on food handouts from donor agencies and the government. The land reform presented the new farmers with multiple land use patterns and livelihood opportunities. In addition, the thesis locates the current programme in the context of previous post-colonial agrarian reforms in Mwenezi. It also emphasizes the importance of diversifying rural livelihood portfolios and argues for the establishment of smallholder irrigation schemes in Mwenezi using water from the Manyuchi dam, the fourth largest dam in Zimbabwe. -

European Journal of Social Sciences Studies GOLD ORE WASTE MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES at RENCO MINE, ZIMBABWE

European Journal of Social Sciences Studies ISSN: 2501-8590 ISSN-L: 2501-8590 Available on-line at: www.oapub.org/soc doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1419529 Volume 3 │ Issue 3 │ 2018 GOLD ORE WASTE MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES AT RENCO MINE, ZIMBABWE Tatenda Mutsvanga1, Jemitias Mapira2i, Nyashadzashe Ngaza3 1BSc Honours Student, Geography & Environmental Science, Great Zimbabwe University, Zimbabwe 2Professor in Geography & Environmental Science, Great Zimbabwe University, Zimbabwe 3Lecturer in Chemistry, Great Zimbabwe University, Zimbabwe Abstract: The question of the sustainability of a mine is extremely difficult to answer, and requires substantive data and other issues to be put into context. This study highlights the major types of waste that are accumulating in a mine both surface and underground. The study also reveals what has been done by Renco Mine in dealing with waste associated with the mining of gold. It shows that little has been done in the reduction of waste generated by mining activities. The issue of waste management is correctly perceived to be a major issue for municipal councils and the manufacturing, construction and chemicals industries. There is less recognition, however, of the vastly larger quantity of solid wastes produced by the mining industry. The reasons for this are most likely due to the perceived relatively benign nature of mine wastes, remoteness from populations, apparent success in mine waste management, or other factors. Waste rock is generally the only waste type which could pose a significant long term environmental threat, as it could contain significant sulfide mineralization. This paper examines waste management challenges at Renco Mine (Zimbabwe) and makes several recommendations at the end. -

Masvingo Province

School Level Province Ditsrict School Name School Address Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA FASHU SCH BIKITA MINERALS CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA MAMUTSE SECONDARY MUCHAKAZIKWA VILLAGE CHIEF BUDZI BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIRIVENGE MUPAMHADZI VILLAGE WARD 12 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita BUDIRIRO VILLAGE 1 WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHENINGA B WARD 2, CHF;MABIKA, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIKWIRA BETA VILLAGE,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE,WARD 16 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHINYIKA VILLAGE 23 DEVURE WARD 26 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIPENDEKE CHADYA VILLAGE, CHF ZIKI, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRIMA RUGARE VILLAGE WARD 22, CHIEF;MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRUMBA TAKAWIRA VILLAGE, WARD 9, CHF; MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHISUNGO MBUNGE VILLAGE WARD 21 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIZONDO CHIZONDO HIGH,ZINDOVE VILLAGE,WARD 2,CHIEF MABIKA Secondary Masvingo Bikita FAMBIDZANAI HUNENGA VILLAGE Secondary Masvingo Bikita GWINDINGWI MABHANDE VILLAGE,CHF;MUKANGANWI, WRAD 13, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUDADISA ZINAMO VILLAGE, WARD 20,CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUSHINGIRIRA MUKANDYO VILLAGE,BIKITA SOUTH, WARD 6 Secondary Masvingo Bikita MACHIRARA CHIWA VILLAGE, CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANGONDO MUSUKWA VILLAGE WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANUNURE DEVURE RESETTLEMENT VILLAGE 4A CHIEF BUDZI Secondary Masvingo Bikita MARIRANGWE HEADMAN NEGOVANO,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MASEKAYI(BOORA) -

An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004

AN AGRARIAN HISTORY OF THE MWENEZI DISTRICT, ZIMBABWE, 1980-2004 KUDAKWASHE MANGANGA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.PHIL IN LAND AND AGRARIAN STUDIES IN THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT, UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE November 2007 DR. ALLISON GOEBEL (QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY, CANADA) DR. FRANK MATOSE (PLAAS, UWC) ii ABSTRACT An Agrarian History of the Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe, 1980-2004 Kudakwashe Manganga M. PHIL Thesis, Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies, Department of Government, University of the Western Cape. The thesis examines continuity and change in the agrarian history of the Mwenezi district, southern Zimbabwe since 1980. It analyses agrarian reforms, agrarian practices and development initiatives in the district and situates them in the localised livelihood strategies of different people within Dinhe Communal Area and Mangondi Resettlement Area in lieu of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) since 2000. The thesis also examines the livelihood opportunities and challenges presented by the FTLRP to the inhabitants of Mwenezi. Land reform can be an opportunity that can help communities in drought prone districts like Mwenezi to attain food security and reduce dependence on food handouts from donor agencies and the government. The land reform presented the new farmers with multiple land use patterns and livelihood opportunities. In addition, the thesis locates the current programme in the context of previous post-colonial agrarian reforms in Mwenezi. It also emphasizes the importance of diversifying rural livelihood portfolios and argues for the establishment of smallholder irrigation schemes in Mwenezi using water from the Manyuchi dam, the fourth largest dam in Zimbabwe. -

PARKS and WILD LIFE ACT Acts 14/1975, 42/1976 (S

TITLE 20 TITLE 20 Chapter 20:14 PREVIOUS CHAPTER PARKS AND WILD LIFE ACT Acts 14/1975, 42/1976 (s. 39), 48/1976 (s. 82), 4/1977, 22/1977, 19/1978, 5/1979, 4/1981 (s. 19), 46/1981, 20/1982 (s.19 and Part XXVI), 31/1983, 11/1984, 35/1985, 8/1988 (s. 164), 1/1990, 11/1991 (s. 24), 22/1992 (s. 14); 19/2001; 22/2001; 13/2002. R.G.Ns 1135/1975, 52/1977, 126/1979, 294/1979, 265/1979, 294/1979, 748/1979; S.Is 675/1979, 632/1980, 640/1980, 704/1980, 773/1980, 781/1980, 786/1980, 139/1981, 140/1981, 181/1981, 183/1981, 639/1981, 860/1981, 139/1982, 140/1982, 337/1983, 454/1983, 123/1991 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. PART II PARKS AND WILD LIFE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY 3. Establishment of Parks and Wild Life Management Authority. 4. Functions of Parks and Wild Life Management Authority. 5. Establishment and composition of Parks and Wild Life Management Authority Board. 6. Minister may give Board policy directions. 7. Minister may direct Board to reverse, suspend or rescind its decisions or actions. 8. Execution of contracts and instruments by Authority. 9. Reports of Authority. 10. Appointment and functions of Director-General and Directors of Authority. 11. Appointment of other staff of Authority. PART IIA FINANCIAL PROVISIONS 12. Funds of Authority. 13. Financial year of Authority. 14. Annual programmes and budgets of Authority. 15. Investment of moneys not immediately required by Authority. 16. Accounts of Authority. -

Rural Highway Service Centres and Rural Livelihoods Diversity: a Case of Ngundu Halt in Zimbabwe

Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 5(17) RURAL HIGHWAY SERVICE CENTRES AND RURAL LIVELIHOODS DIVERSITY: A CASE OF NGUNDU HALT IN ZIMBABWE Bernard Chazovachii, Maxwell Chuma, Lecturers Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT This study seeks to assess the impact of rural high way service centres on livelihood diversity. The establishment of Ngundu rural highway service centre was an approach to assist highway travelers and local residents in accessing essential services without going off- route. Since the establishment of these highway service centers, little has been realized in terms of their utility. Data was collected using questionnaires; participatory observation and interviews and presented in the form of graphs; pie charts and tables. The rural highway service centre benefited local residents in its sphere of influence through social welfare provision; employment creation; recreation and as agricultural inputs collection centres. However the opportunity on livelihoods diversity by locals and travelers to enjoy their need has been abused .Both locals and travelers have turned the centre into risk livelihood strategies arena, crime and deviant behavior proliferated turning it into life threatening zone. Therefore need is there to reinforce overnight surveillance through the neighborhood watch for security and welfare of genuine dealers and travelers for sustainable and investment confident and promotion climate. KEY WORDS Rural highway service centre; Livelihood; Diversity; Ngundu halt; Zimbabwe. Rural highway service centres are stopover towns near major transportation routes. According to the Department of Transport, Energy and Infrastructure, (2008), rural highway service centres are also called rest areas in Australia, therefore are public facilities located next to a large thoroughfare such as highway, expressway or freeway at which drivers and passengers can rest, eat, refuel without exiting on to secondary roads. -

Vol IV Southeast Lowveld, Zimbabwe

TOURISM, CONSERVATION & SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT VOLUME IV THE SOUTH-EAST LOWVELD, ZIMBABWE Final Report to the Department for International Development Principal Authors: Goodwin, H.J., Kent, I.J., Parker, K.T., & Walpole, M.J. Project Managers: Goodwin, H.J.(Project Director), Swingland, I.R., Sinclair, M.T.(to August 1995), Parker, K.T.(from August 1995) Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE), Institute of Mathematics and Statistics (IMS), University of Kent April 1997 This is one of four final reports produced at the end of a three year, Department for International Development funded project. Three case study reports (Vols. II-IV) present the research findings from the individual research sites (Keoladeo NP, India, Komodo NP, Indonesia, and the south-east Lowveld, Zimbabwe). The fourth report (Vol. I) contains a comparison of the findings from each site. Contextual data reports for each site, and methodological reports, were compiled at the end of the first and second years of the project respectively. The funding for this research was announced to the University of Kent by the ODA in December 1993. The original management team for the project consisted of, Goodwin, H.J., (Project Director), Swingland, I.R. and Sinclair, M.T. In August 1995, Sinclair was replaced by Parker, K.T. Principal Authors: • Dr Harold Goodwin (Project Director, DICE) • Mr Ivan Kent (DICE) • Dr Kim Parker (IMS) • Mr Matt Walpole (DICE) The collaborating institution in Zimbabwe was the Department of Geography, University of Zimbabwe (UZ). The research co-ordinator in Zimbabwe was Mrs Robin Heath. Research in the south-east lowveld was conducted by Dr Harold Goodwin (DICE), with the assistance of Mr T. -

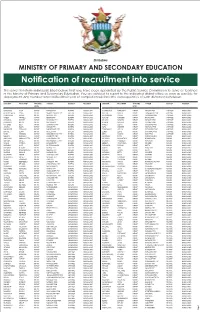

Notification of Recruitment Into Service

Zimbabwe Notification of recruitment into service This serves to inform individuals listed below, that you have been appointed by the Public Service Commission to serve as teachers in the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. You are advised to report to the indicated district office as soon as possible for deployment. Any member who falsified their year of completion will face the consequences of such dishonest behaviour. -

MASVINGO PROVINCE - Basemap

MASVINGO PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland East Mpinda Musuma Msilahove Ntabamhlope Ntabamhlope 30 Hunters Mlezu 19 27 Chikwava 8 Munyanyi Chipfatsura Mushunje Rowa 6 C h i c a m b a e a l 3 Road 15 31 4 33 R 25 23 12 Lancashire Chipwanya 1 31 13 Gunde Chapwanya 10 15 Burma Madilisa Nkululeko Connemara Murezi Mombeyarara 4 Gunde Central Garamwera Bepe 2 11 Valley Locations Nyama Masvori Chirinda 12 14 Connemara St Patricks Estates 8 14 CHIKOMBA 2 11 Chiweshe Zumbare KWEKWE 7 12 7 Nyama 12 Gombe 13 Chiwenga 9 Berzerly 9 St. Muchakata 13 Maburutse 3 Matanda Bridge 11 St. Gwindingwi 10 3 Patricks Chiundura 5 Makumbe Richards Marange Madhikani 16 Murambinda Nyashanu Bazeley Province Capital 2 Maboleni Marange 24 7 Mvuma 24 Nyashanu Murambinda Nyashanu 18 Bridge 20 Mambwere Maboleni 2 Nerutanga 10 Mvuma 13 Denhere 8 O Cambrai 20 Bakorenhema Athens d Netherburn N y a m a f u f u 36 21 4 z Broadside Buhera Nhamo i Chitora Chipendeke s 15 Lalapanzi d 22 Buhera 18 Nyangani Zvipiripiri 17 Chikwariro 19 Chitora BANTI n 6 Lalapanzi 6 14 Town a 17 Mtao Bambazonke l W h i t e w a t e r Whahwa 16 Bwizi O 5 1 Mudanda 20 Nzvenga d d Fairfield z i Gutaurare Lower i Hlabano Mangwande Insukamini Dambara Betera 26 Mpudzi M Gweru 8 16 14 1 I n s u k a m i n i BUHERA MUTARE Muromo 19 4 Mudanda 22 Makepesi O M Vungu Sino Rukundo 11 Lynwood Driefontein Nyazvidzi Viriri 17 23 Place of Local Importance Lower 25 d Zimbabwe Driefontein St Andrews z 27 a Gweru Welcome i n Totonga Isolation 1 Nyazvidzi i Muwonde Felixburg 16 Madzimbashuro Zvipiripiri Masasi c Soti a Mkoba