Primary External Dacryocystorhinostomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icare Eye Hospital Rate List 2015

ICARE EYE HOSPITAL & POST GRADUATE INSTITUTE E-3A, Sector – 26, Noida – 201301 Tel:- 0120-2477600 / 02, Counselor: 0120-2477621 Fax: 0120-2556389 / Appointments: 9811880015 Email: [email protected] / Web: www.icarehospital.org ICARE EYE HOSPITAL RATE LIST 2015 S No. PARTICULAR TARIFF (₹) I CONSULTATION NEW PATIENT VALID FOR 7 DAYS (FIRST TIME CONSULTATION : REGISTRATION + 1 ₹ 600/- CONSULTATION) 2 REVIEW CONSULTATION VALID FOR 7 DAYS ₹ 500/- 3 EMERGENCY CONSULTATION FOR 7 DAYS ₹ 800/- 4 LOW VISUAL AIDS ASSESSMENT CHARGES ₹ 600/- 5 VISION THERAPY CHARGES FOR PER SITTING ₹ 200/- 6 COST OF VISION THERAPY SOFTWARE (CD) ₹ 6,000/- 7 AMBLYOPIA (CD) ₹ 4,000/- II INVESTIGATIONS 1 Digital F.F.A (Fundus Fluoroscein Angiography)(Inclusive of Fundus photo) ₹ 2,500/- 2 Colour Fundus Photo - Digital ₹ 600/- 3 Colour Slit-lamp photo ₹ 600/- 4 Duplicate color prints (FFA/OCT/CLINICAL PHOTO) ₹ 300/- 5 Orthoptic ₹ 250/- 6 OCT (Optical Coherence Tomography) ₹ 2,500/- A Repeat OCT (within 2 months) with printout ₹ 800/- B Anterior Segment OCT ₹ 2,500/- 7 Ultrasonography (U/S) A A Scan – Single Eye ₹ 600/- B B Scan – Single Eye ₹ 1,000/- C UBM - Single Eye ₹ 1,500/- 8 Computerized field analysis A Humphrey Visual Fields (HVF) both eyes ₹ 1,500/- B Humphrey Visual Fields (HVF) One eye ₹ 750/- 9 Diurnal Variation of Tension (Day DVT ) A 5 times tension (Done in both eyes)] ₹ 500/- Page 1 10 Pachymetry (Both eyes) A Ultrasound (Central Corneal Thickness- CST) ₹ 600/- B Optical ₹ 600/- 11 Corneal Topography A Single Eye ₹ 1,000/- B Both Eyes ₹ 2,000/- 12 -

Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Diagnostic Evaluation and Medical Management of Moderate-Severe Dry Eye Disease (DED) (L36232)

Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Diagnostic Evaluation and Medical Management of Moderate-Severe Dry Eye Disease (DED) (L36232) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT NUMBER JURISDICTION STATE(S) First Coast Service Options, Inc. A and B MAC 09101 - MAC A J - N Florida First Coast Service Options, Inc. A and B MAC 09102 - MAC B J - N Florida First Coast Service Options, Inc. A and B MAC 09201 - MAC A J - N Puerto Rico Virgin Islands First Coast Service Options, Inc. A and B MAC 09202 - MAC B J - N Puerto Rico First Coast Service Options, Inc. A and B MAC 09302 - MAC B J - N Virgin Islands LCD Information Document Information LCD ID Original Effective Date L36232 For services performed on or after 11/22/2015 LCD Title Revision Effective Date Diagnostic Evaluation and Medical Management of For services performed on or after 01/08/2019 Moderate-Severe Dry Eye Disease (DED) Revision Ending Date Proposed LCD in Comment Period N/A N/A Retirement Date Source Proposed LCD N/A DL36232 Notice Period Start Date AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright 10/08/2015 Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are Notice Period End Date copyright 2019 American Medical Association. All Rights 11/22/2015 Reserved. Applicable FARS/HHSARS apply. Current Dental Terminology © 2019 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2019, the American Hospital Association, Created on 01/02/2020. Page 1 of 12 Chicago, Illinois. -

Diagnostic Nasal/Sinus Endoscopy, Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (FESS) and Turbinectomy

Medical Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................................. 7/10/2021 Next Review Date ....................................... 3/15/2022 Coverage Policy Number .................................. 0554 Diagnostic Nasal/Sinus Endoscopy, Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (FESS) and Turbinectomy Table of Contents Related Coverage Resources Overview .............................................................. 1 Balloon Sinus Ostial Dilation for Chronic Sinusitis and Coverage Policy ................................................... 2 Eustachian Tube Dilation General Background ............................................ 3 Drug-Eluting Devices for Use Following Endoscopic Medicare Coverage Determinations .................. 10 Sinus Surgery Coding/Billing Information .................................. 10 Rhinoplasty, Vestibular Stenosis Repair and Septoplasty References ........................................................ 28 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and do not make coverage determinations. References to standard benefit plan language and coverage determinations do not apply to those clients. Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service Agreement, Evidence -

672 Rapid Development of Visual Field Defects Associated with Vigabatrin Therapy

Case report The incidence of penetrating injury is thought in part to be due to globe shape, with myopic eyes being at A 64-year-old woman presented to eye casualty with a greater risk. Vohra and Good7 suggest, however, that a second episode of right dacryocystitis. The visual acuity medial canthal approach is the safest, especially in larger was 6/6 bilaterally. She was given a 7 day course of oral globes? This is because of a reduction in the equatorial amoxicillin 500 mg t.d.s. with flucloxacillin 250 mg q.d.s. width to axial length ratio in high degrees of axial and was reviewed when the infection had settled. myopia. Inflammation of the tissues surrounding the Syringing showed patent canaliculi with regurgitation usual landmarks, for example following dacryocystitis, and she was listed for dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) as in this patient, can alter the anatomy of the injection under local anaesthesia. site and increase the risk of perforation. MeyerS reports In the anaesthetic room the patient was sedated with some success with topical anaesthetic techniques which 2.5 mg of intravenous midazolam. Two drops of would eliminate the risk of penetrating ocular injury. amethocaine were instilled into both eyes. Two puffs of Early diagnosis and treatment of ocular perforations 2% lignocaine spray were applied to the right nasal are essential for a good visual outcome6,9 and therefore passage. A nasal pack of 5% cocaine with adrenaline was there should be a high index of suspicion in those cases placed in the right nasal antrum. A local anaesthetic where the injections are excessively painful, or mixture containing 4 ml of 2% lignocaine with 1:200 000 ineffective, or if there is hypotony of the globe or a adrenaline and 4 ml of 0.75% bupivacaine was decrease in visual acuity. -

Quality of Vision in Eyes with Epiphora Undergoing Lacrimal Passage Intubation

Quality of Vision in Eyes With Epiphora Undergoing Lacrimal Passage Intubation SHIZUKA KOH, YASUSHI INOUE, SHINTARO OCHI, YOSHIHIRO TAKAI, NAOYUKI MAEDA, AND KOHJI NISHIDA PURPOSE: To investigate visual function and optical PIPHORA, THE MAIN COMPLAINT OF PATIENTS WITH quality in eyes with epiphora undergoing lacrimal passage lacrimal passage obstruction, causes blurred vision, intubation. discomfort, and skin eczema, and may even cause so- E DESIGN: Prospective case series. cial embarrassment. Several studies have assessed the qual- METHODS: Thirty-four eyes of 30 patients with ity of life (QoL) or vision-related QoL of patients suffering lacrimal passage obstruction were enrolled. Before and from lacrimal disorders and the impact of surgical treat- 1 month after lacrimal passage intubation, functional vi- ments on QoL, using a variety of symptom-based question- sual acuity (FVA), higher-order aberrations (HOAs), naires.1–8 According to these studies, epiphora negatively lower tear meniscus, and tear clearance were assessed. affects QoL physically and socially; however, surgical An FVA measurement system was used to examine treatment can improve QoL. Increased tear meniscus changes in continuous visual acuity (VA) over time, owing to inadequate drainage contributes to blurry and visual function parameters such as FVA, visual main- vision.9 However, quality of vision (QoV) has not been tenance ratio, and blink frequency were obtained. fully quantified in eyes with epiphora, and the effects of Sequential ocular HOAs were measured for 10 seconds lacrimal surgery on such eyes are unknown. after the blink using a wavefront sensor. Aberration Dry eye, a clinically significant multifactorial disorder of data were analyzed in the central 4 mm for coma-like, the ocular surface and tear film, may cause visual distur- spherical-like, and total HOAs. -

Cataract Surgery

Cataract surgery From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (May 2011) Cataract surgery Intervention Cataract in Human Eye- Magnified view seen on examination with a slit lamp ICD-9-CM 13.19 MeSH D002387 Cataract surgery is the removal of the natural lens of the eye (also called "crystalline lens") that has developed an opacification, which is referred to as a cataract. Metabolic changes of the crystalline lens fibers over time lead to the development of the cataract and loss of transparency, causing impairment or loss of vision. Many patients' first symptoms are strong glare from lights and small light sources at night, along with reduced acuity at low light levels. During cataract surgery, a patient's cloudy natural lens is removed and replaced with a synthetic lens to restore the lens's transparency.[1] Following surgical removal of the natural lens, an artificial intraocular lens implant is inserted (eye surgeons say that the lens is "implanted"). Cataract surgery is generally performed by an ophthalmologist (eye surgeon) in an ambulatory (rather than inpatient) setting, in a surgical center or hospital, using local anesthesia (either topical, peribulbar, or retrobulbar), usually causing little or no discomfort to the patient. Well over 90% of operations are successful in restoring useful vision, with a low complication rate.[2] Day care, high volume, minimally invasive, small incision phacoemulsification with quick post-op recovery has become the standard of care in cataract surgery all over the world. -

Fixing Patients' Problems

CAN TABLETS WORK FOR EMR? P. 12 • CODING TIPS FOR CROSS-LINKING P. 16 A FRESH ANGLE ON RESIDENT TRAINING P. 68 • SIXTH CRANIAL NERVE DYSFUNCTION IN KIDS P. 72 Review of Ophthalmology Vol. XXIV, No. 4 • April 2017 • Fighting for Patient Care • Avoiding Problems Using OCT • Managing Refractive Surprises Problems • Optical Biometry Roundup Care • Avoiding No. 4 • April 2017 • Fighting for Patient Review of Ophthalmology Vol. XXIV, STEM THE TIDE OF EXCESSIVE TEARING P. 76 • POST-INJECTION IOP SPIKES P. 96 April 2017 reviewofophthalmology.com Fixing Patients’ Problems Expert surgeons give you the tools you need to succeed. ALSO INSIDE: Sizing Up Optical Biometers P. 58 001_rp0417_fc-WB.indd 1 3/24/17 12:52 PM VISIT US AT ASCRS BOOTH #1022 It’s all in CHOOSE A SYSTEM THAT EMPOWERS YOUR EVERY MOVE. Technique is more than just the motions. Purposefully engineered for exceptional versatility and high-quality performance, the WHITESTAR SIGNATURE® PRO Phacoemulsification System gives you the clinical flexibility, confidence and control to free your focus for what matters most in each procedure. How do you phaco? Join the conversation at WWW.ABBOTTPHACO.COM Rx Only INDICATIONS: The WHITESTAR SIGNATURE® PRO System is a modular ophthalmic microsurgical system that facilitates anterior segment (cataract) surgery. The modular design allows the users to configure the system to meet their surgical requirements. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: Risks and complications of cataract surgery may include broken ocular capsule or corneal burn. This device is only to be used by a trained, licensed physician. ATTENTION: Reference the labeling for a complete listing of Indications and Important Safety Information. -

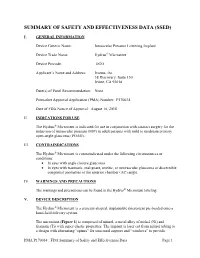

Summary of Safety and Effectivness (SSED)

SUMMARY OF SAFETY AND EFFECTIVENESS DATA (SSED) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Device Generic Name: Intraocular Pressure Lowering Implant Device Trade Name: Hydrus® Microstent Device Procode: OGO Applicant’s Name and Address: Ivantis, Inc. 38 Discovery, Suite 150 Irvine, CA 92618 Date(s) of Panel Recommendation: None Premarket Approval Application (PMA) Number: P170034 Date of FDA Notice of Approval: August 10, 2018 II. INDICATIONS FOR USE The Hydrus® Microstent is indicated for use in conjunction with cataract surgery for the reduction of intraocular pressure (IOP) in adult patients with mild to moderate primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). III. CONTRAINDICATIONS The Hydrus® Microstent is contraindicated under the following circumstances or conditions: • In eyes with angle closure glaucoma • In eyes with traumatic, malignant, uveitic, or neovascular glaucoma or discernible congenital anomalies of the anterior chamber (AC) angle. IV. WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS The warnings and precautions can be found in the Hydrus® Microstent labeling. V. DEVICE DESCRIPTION The Hydrus® Microstent is a crescent-shaped, implantable microstent pre-loaded onto a hand-held delivery system. The microstent (Figure 1) is composed of nitinol, a metal alloy of nickel (Ni) and titanium (Ti) with super-elastic properties. The implant is laser cut from nitinol tubing to a design with alternating “spines” for structural support and “windows” to provide PMA P170034: FDA Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data Page 1 outflow pathways for aqueous humor. After laser cutting, the shape of the implant is heat-set to a curvature intended to match the curvature of Schlemm’s canal and is electro- polished to create a smooth surface. The microstent is approximately 8 mm in overall length with major and minor axes of 292 µm and 185 µm, respectively. -

Operative Dictations in Ophthalmology Eric D

Operative Dictations in Ophthalmology Eric D. Rosenberg • Alanna S. Nattis Richard J. Nattis Editors Operative Dictations in Ophthalmology Editors Eric D. Rosenberg Alanna S. Nattis Ophthalmology Resident Cornea and Refractive Surgery Fellow Department of Ophthalmology Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island New York Medical College Rockville Centre, NY, USA Valhalla, NY, USA Richard J. Nattis Chief of Ophthalmology and Clinical Professor Department of Ophthalmology Good Samaritan Hospital West Islip, NY, USA ISBN 978-3-319-45494-8 ISBN 978-3-319-45495-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45495-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017932292 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Curriculum Vitae

Kashkouli MB, CV CURRICULUM VITAE Mohsen Bahmani Kashkouli, MD Section Subject I Personal Information II 1. Executive Position 2. Journal Editor 3. Organizing a meeting 4. Journals’ reviewer, 5. Establishing an organization III Education IV Work Experience V Trained Fellows VI Edited Books/ Chapters VII Peer Reviewed Paper Publications VIII Courses Attended IX Directing Workshops/Courses/ Symposia X Conference Abstracts XI Invited (Guest) Speaker XII Awards XIII Innovations XIV Ongoing Research Projects XV Referees XVI Interests XVII Affiliations 1 Kashkouli MB, CV I. PERSONAL INFORMATION NAME: Mohsen Bahmani Kashkouli WORK ADDRESS University Hospital Private Office Rassoul Akram Hospital No.:49, West Brazil- South Sattarkhan-Niayesh Avenue Sheikhbahaee intersection, POBox: 14455-364 Tehran, Iran Tehran, Iran Phone: +98 21 66559595 Phone: +98 21 88065620 Fax: +98 21 66509162 Fax: +98 21 66558811 Email [email protected] DATE OF BIRTH: 09/January/1967 PLACE OF BIRTH: Gachsaran , Iran Language: Farsi, English, Turkish II. SCIENTIFIC & EXECUTIVE POSITIONS 1. Executive Positions 2. Professor, Head of Oculo-Facial Plastic Surgery, Rassoul Akram Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences (www.iums.ac.ir), Tehran, Iran. 3. Regional (Iran and Turkey) Vice President of Middle East African Council of Ophthalmology (MEACO).(www.meaco.org), Since Nov. 2019. 4. Vice President of Middle East African Council of Ophthalmology (MEACO) in Middle East (www.meaco.org), Since 2012. 5. Vice President, Middle East African Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (MEASOPRS, www.meaco.org ), Since June 2016. 6. Scientific Coordinator, Middle East African Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (MEASOPRS, www.meaco.org ), 2012-2016. 7. Scientific Director and chair of International relation section, Iranian Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Suregry (IrSOPRS, www.irso.org/irsoprs), Tehran, Iran, Since 2007. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

1 Annex 2. AHRQ ICD-9 Procedure Codes 0044 PROC-VESSEL

Annex 2. AHRQ ICD-9 Procedure Codes 0044 PROC-VESSEL BIFURCATION OCT06- 0201 LINEAR CRANIECTOMY 0050 IMPL CRT PACEMAKER SYS 0202 ELEVATE SKULL FX FRAGMNT 0051 IMPL CRT DEFIBRILLAT SYS 0203 SKULL FLAP FORMATION 0052 IMP/REP LEAD LF VEN SYS 0204 BONE GRAFT TO SKULL 0053 IMP/REP CRT PACEMAKR GEN 0205 SKULL PLATE INSERTION 0054 IMP/REP CRT DEFIB GENAT 0206 CRANIAL OSTEOPLASTY NEC 0056 INS/REP IMPL SENSOR LEAD OCT06- 0207 SKULL PLATE REMOVAL 0057 IMP/REP SUBCUE CARD DEV OCT06- 0211 SIMPLE SUTURE OF DURA 0061 PERC ANGIO PRECEREB VES (OCT 04) 0212 BRAIN MENINGE REPAIR NEC 0062 PERC ANGIO INTRACRAN VES (OCT 04) 0213 MENINGE VESSEL LIGATION 0066 PTCA OR CORONARY ATHER OCT05- 0214 CHOROID PLEXECTOMY 0070 REV HIP REPL-ACETAB/FEM OCT05- 022 VENTRICULOSTOMY 0071 REV HIP REPL-ACETAB COMP OCT05- 0231 VENTRICL SHUNT-HEAD/NECK 0072 REV HIP REPL-FEM COMP OCT05- 0232 VENTRI SHUNT-CIRCULA SYS 0073 REV HIP REPL-LINER/HEAD OCT05- 0233 VENTRICL SHUNT-THORAX 0074 HIP REPL SURF-METAL/POLY OCT05- 0234 VENTRICL SHUNT-ABDOMEN 0075 HIP REP SURF-METAL/METAL OCT05- 0235 VENTRI SHUNT-UNINARY SYS 0076 HIP REP SURF-CERMC/CERMC OCT05- 0239 OTHER VENTRICULAR SHUNT 0077 HIP REPL SURF-CERMC/POLY OCT06- 0242 REPLACE VENTRICLE SHUNT 0080 REV KNEE REPLACEMT-TOTAL OCT05- 0243 REMOVE VENTRICLE SHUNT 0081 REV KNEE REPL-TIBIA COMP OCT05- 0291 LYSIS CORTICAL ADHESION 0082 REV KNEE REPL-FEMUR COMP OCT05- 0292 BRAIN REPAIR 0083 REV KNEE REPLACE-PATELLA OCT05- 0293 IMPLANT BRAIN STIMULATOR 0084 REV KNEE REPL-TIBIA LIN OCT05- 0294 INSERT/REPLAC SKULL TONG 0085 RESRF HIPTOTAL-ACET/FEM