The David Mathews Administration of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of James Mathews Sr

Descendants of James Mathews Sr. Greg Matthews Table of Contents .Descendants . .of . .James . .Mathews . .Sr. 1. .First . Generation. 1. .Source . .Citations . 2. .Second . Generation. 3. .Source . .Citations . 9. .Third . Generation. 15. .Source . .Citations . 32. .Fourth . Generation. 47. .Source . .Citations . 88. .Fifth . Generation. 115. .Source . .Citations . 147. .Sixth . Generation. 169. .Source . .Citations . 192. Produced by Legacy Descendants of James Mathews Sr. First Generation 1. James Mathews Sr. {M},1 son of James Mathews and Unknown, was born about 1680 in Surry County, VA and died before Mar 1762 in Halifax County, NC. Noted events in his life were: • First appearance: First known record for James is as a minor in the Court Order Books, 4 Jun 1688, Charles City County, Virginia.2 Record mentions James and brother Thomas Charles Matthews and that both were minors. Record also mentions their unnamed mother and her husband Richard Mane. • Militia Service: Was rank soldier on 1701/2 Charles City County militia roll, 1702, Charles City County, Virginia.3 • Tax List: Appears on 1704 Prince George County Quit Rent Roll, 1704, Prince George County, Virginia.4 • Deed: First known deed for James Mathews Sr, 28 Apr 1708, Surry County, VA.5 On 28 Apr 1708 James Mathews and wife Jeane sold 100 acres of land to Timothy Rives of Prince George County. The land was bound by Freemans Branch and John Mitchell. Witnesses to the deed were William Rives and Robert Blight. • Deed: First land transaction in North Carolina, 7 May 1742, Edgecombe County, NC.6 Was granted 400 acres in North Carolina by the British Crown in the first known deed for James in NC. -

Surname Notes Abbott Family Abbott, James Scotland and Virginia Abel

Surname Notes Abbott Family Abbott, James Scotland and Virginia Abel/Abel - Franklin Families Abshire Family Bedford, Franklin and Tazewell Counties Adams and Vaden Families Adams Family Massachusetts Adams Family Campbell County, Virginia Adams, Lela C. Biography Adams, Thomas Albert 1839-1888 Addison, Lucy Biography 1861-1937 Adkins Family Pittsylvania County, Virginia Adkins, John Ward Airheart/Airhart/Earhart Family Aker, James Biography 1871-1986 Akers Family Floyd County, Virginia Albert Family Alcorn-Lusk Family MSS C-2 Beverly R. Hoch Collection Alderman, Edwin Anderson Biography 1861-1931 Alderman, John Perry Biography - d. 1995 Alderson Family Alexander Family Alexander Family MSS C-2 Beverly R. Hoch Collection Alexander-Gooding Family MSS C-2 Beverly R. Hoch Collection Alford-Liggon Family MSS C-2 Beverly R. Hoch Collection Aliff/Ayliffe Family Allan Family Allen Family Little Creek, Pulaski County, Virginia Carroll County, Virginia - Court Allen Family Proceedings Allen Family MSS C-2 Beverly R. Hoch Collection Allen, Cary Biographty 1767-1795 Allen, George Allen, Robert N. Biography 1889-1831 Allen, Susan Biography Allen, William R. Fluvanna County, Virginia (Oversize File) Allerton Family Alley Family "Allees All Around" Allison Family MSS C-2 Beverly R. Hoch Collection Almond, James Lindsay, Jr. Almond, Russell E,. Biography - d.1905 Alphin Family Alt/Ault Family (Oversize File) Altig/Altick/Altice/Attic Altizer Family Ames Family Ammon Family Ammonet Family Anastasia - Manahan, Mrs. Anna Biography d. 1984 Surname Notes Anderson Family Craig County, Virginia Anderson Family George Smith Anderson (Oversize File) MSS C-2 Beverly R. Hoch Collection (3 Anderson Family folders) Anderson Famiy Prince George County, Virginia Anderson, Wax, Kemper Families Anderson, Cassandra M. -

Nomination of Hon. Sylvia M. Burwell Hearing Committee

S. Hrg. 113–63 NOMINATION OF HON. SYLVIA M. BURWELL HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOMINATION OF HON. SYLVIA M. BURWELL, TO BE DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET ARPIL 9, 2013 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 80–570 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware Chairman CARL LEVIN, Michigan TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MARK L. PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JON TESTER, Montana RAND PAUL, Kentucky MARK BEGICH, Alaska MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota RICHARD J. KESSLER, Staff Director LAWRENCE B. NOVEY, Chief Counsel for Governmental Affairs TROY H. CRIBB, Chief Counsel for Governmental Affairs KRISTINE V. LAM, Professional Staff Member DEIRDRE G. ARMSTRONG, Professional Staff Member KEITH B. ASHDOWN, Minority Staff Director ANDREW C. DOCKHAM, Minority Chief Counsel TRINA D. SHIFFMAN, Chief Clerk LAURA W. KILBRIDE, Hearing Clerk (II) C -

Elizabeth Shown Mills

ELIZABETH SHOWN MILLS Certified GenealogistSM Certified Genealogical LecturerSM Fellow & Past President, American Society of Genealogists Past President, Board for Certification of Genealogists 141 Settlers Way, Hendersonville, TN 37075 • [email protected] DATE: 8 February 2019 (updated 12 April 2021) REPORT TO: File SUBJECT Augusta County & the Virginia Frontier, Mills & Watts: Initial Survey of Published Literature, principally Bockstruck’s Virginia’s Colonial Soldiers1 Chalkley’s Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish in Virginia2 Kegley’s Virginia Frontier3 Nelson’s Report on the Chalkley Manuscripts4 Peyton’s History of Augusta County5 Rev. John Craig’s List of Baptisms6 OBJECTIVE: This survey of key published resources for eighteenth-century Augusta County seeks evidence to better identify the Mills and Watts families who settled Southwest Virginia and (eventually) assemble them into family groups. BACKGROUND: Targeted research in several areas of Virginia and North Carolina has yielded several Millses of particular interest with proved or alleged ties to Augusta: Cluster 1: Goochland > Albemarle > Amherst WILLIAM MILLS & WIFE MARY appear in Goochland County as early as 1729. As a resident of Goochland County, William requested land on Pedlar River, a branch of James River. In 1745, the tract he chose was cut away into the new county of Albemarle (later Amherst); it lay just across the Blue Ridge from the Forks of the James River land of a John Mills who is said to have lived contemporaneously in Augusta. William and Mary’s daughter Sarah married Thomas Watts of adjacent Lunenburg > Bedford about 1748. Many online 1 Lloyd DeWitt Bockstruck, Virginia’s Colonial Soldiers (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1988). -

Vertical File

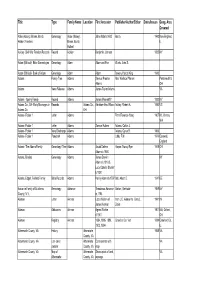

Title Type Family Name Location First Ancestor Publisher/Author/Editor Dates/Issues Geog. Area Covered Abbe (Abbey), Brown, Burch, Genealogy Abbe (Abbey), John Abbe b.1613 Burch 1943 New England, Hulbert Families Brown, Burch, IL Hulbert Ackley- Civil War Pension Records Record Ackley Benjamin Johnson 1832 NY Adam (Biblical)- Bible Genealogies Genealogy Adam Adam and Eve Wurts, John S. Adam (Biblical)- Book of Adam Genealogy Adam Adam Bowen, Harold King 1943 Adams Family Tree Adams Samuel Preston Mrs. Wallace Phorsm Portsmouth & Adams OH Adams News Release Adams James Taylor Adams VA Adams - Spring Family Record Adams James Wamorth? 1832 NY Adams Co., OH- Early Marriages in Records Adams Co., Abraham thru Wilson Ackley, Robert A. 1982 US Adams Co. OH Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams From Florence Hoag 1907 Mt. Vernon, WA Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams Samuel Adams Adams, Calvin J. Adams- Folder 1 Navy Discharge Adams Adams, Cyrus B. 1866 Adams- Folder 1 Pamphlet Adams Lobb, F.M. 1979 Cornwall, England Adams- The Adams Family Genealogy/ Tree Adams Jacob Delmar Harper, Nancy Eyer 1978 OH Adams b.1858 Adams, Broyles Genealogy Adams James Darwin KY Adams b.1818 & Lucy Ophelia Snyder b.1820 Adams, Edgell, Twiford Family Bible Records Adams Henry Adams b.1797 Bell, Albert D. 1947 DE Adriance Family of Dutchess Genealogy Adriance Theodorus Adriance Barber, Gertrude 1959 NY County, N.Y. m.1783 Aikman Letter Aikman Lists children of from L.C. Aikman to Cora L. 1941 IN James Aikman Davis Aikman Obituaries Aikman Agnes Ritchie 1901 MA, Oxford, d.1901 OH Aikman Registry Aikman 1884, 1895, 1896, Crawford Co. -

'O'er Mountains and Rivers': Community and Commerce

MCCARTNEY, SARAH ELLEN, Ph.D. ‘O’er Mountains and Rivers’: Community and Commerce in the Greenbrier Valley in the Late Eighteenth Century. (2018) Directed by Dr. Greg O’Brien. 464 pp. In the eighteenth-century Greenbrier River Valley of present-day West Virginia, identity was based on a connection to “place” and the shared experiences of settlement, commerce, and warfare as settlers embraced an identity as Greenbrier residents, Virginians, and Americans. In this dissertation, I consider the Greenbrier Valley as an early American place participating in and experiencing events and practices that took place throughout the American colonies and the Atlantic World, while simultaneously becoming a discrete community and place where these experiences formed a unique Greenbrier identity. My project is the first study of the Greenbrier Valley to situate the region temporally within the revolutionary era and geographically within the Atlantic World. For many decades Greenbrier Valley communities were at the western edge of Virginia’s backcountry settlements in what was often an “ambiguous zone” of European control and settlers moved in and out of the region with the ebb and flow of frontier violence. Settlers arriving in the region came by way of the Shenandoah Valley where they traveled along the Great Wagon Road before crossing into the Greenbrier region through the mountain passes and rivers cutting across the Allegheny Mountains. Without a courthouse or church, which were the typical elements of community in eighteenth- century Virginia society, until after the American Revolution, Greenbrier settlers forged the bonds of their community through other avenues, including the shared hardships of the settlement experience. -

8Eneal0gical Socieiy^

8ENEAL0GICAL SOCIEIY^ Early Oisfory Vargima aaul Marylanul anJ SEVEN CENTURIES OF LINES - C\a^. w i FHRENCE ONLY WytKe LeigU KinsolTing, B. A.; M. A. (Uuiv, of Va.) c\o Sfuiies in Pre-American and Early American. Colonial Times date microfilm r\ COUNTY Ci\LlFO|RN!/^i™ ™ GLi'^iLrtLOliiCAL SOClEfy r,,,fnCAMERA L!0 -3C<Lp OedicaieJ io CATALOGUE NO g ANNIE LAURIE KINSOLVING Mydy LoTingWifeLoTing^jiyi^e WLosc Body Lies in Hollywood, Richmond WITHDRAWN V MBi"' OT Family Hr History Library SKETCH OF THE AUTHOR (By a Friend) Wythe Leigh Kinsolving, the only son of Rev. Dr. 0. A. Kinsolv- ing and his third wife was born toward the close of the nineteenth century and baptized in St. John's, Halifax, Virginia. Roberta Gary, the first-born child of this marriage, died at the' early age of eight. Gary was a gentle, lovely, fascinating child, like her mother in charm and amiability. She was the only daughter ever bora to her father. Long after her death I found Longfellow's "Res ignation" tenderly copied in his own hand, and upon his desk. She was the second daughter of her mother to leave this world for Paradise. Jane Gorbin died when seven, at beautiful Moss Neck in Garoline; Gary at eight, in the imposing brick rectory at St. John's, Halifax. Wythe, the son, studied Latin at nine, Greek at ten, French and German when twelve or thirteen. He was ready for college at seven teen, after spending four years at the Episcopal High School. In two vears he earned a monitorship on merit, and was ultimately the Head" Monitor of the Episcopal High School. -

A History of Conklin Village, Loudoun County the Mcgraw's Ridge

12/26/2014 History of Conklin Village, McGraw’s Ridge White School A History of Conklin Village, Loudoun County The McGraw’s Ridge “White School” Page | 1 BY LARRY ROEDER, MS This study is copyrighted by Larry Roeder, MS, Dec 26, 2014 3/15/2016 1 12/26/2014 History of Conklin Village, McGraw’s Ridge White School Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Thanks ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Language Related to Race .............................................................................................................. 9 Page | 2 VI 1 The Approach to Schools Chosen for the Research ........................................................... 10 VI 1.1 About prejudice?: .......................................................................................................... 11 VI 2 Horace Adee’s School for White Children on Braddock Road .......................................... 12 VI 3 Western State Hospital and the Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind in Staunton ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 VI 4 McGraw’s Ridge School (White)(summary history) ...................................................... 14 VI 4.1 Enrollment Cards for McGraw’s Ridge Lead New Studies ...................................... -

Children's Stories

CHILDREN’S STORIES The Mathews Family of Clarke County, Alabama, 1800–1948 The original Mathews home of Josiah Allen and Lucy Martin Mathews Table of Contents THE WALDRUMS AND WALKERS................................................................... 1 The Story of the Face in the Well ................................................................................................................ 2 THE MATHEWS.................................................................................................... 5 David Mathews Returns from the Civil War ............................................................................................... 6 THE MCLEODS..................................................................................................... 7 PUGHS AND CHAPMANS ................................................................................... 8 Going Back to South Carolina .................................................................................................................... 9 GROWING UP ....................................................................................................... 9 LEFT AT THE OLD UNION CHURCH............................................................ 10 Cousin Kish .................................................................................................................................................11 Albert Sidney Mathews .............................................................................................................................. 12 Farming .................................................................................................................................................... -

Mat(T)Hews Family Wills

Mat(t)hews Associated Wills of VA, NC, SC, GA and TN All wills have been bookmarked. Simply click on a name on the following pages to be taken to that will. Surname spellings are as they appear in the will. Dates beside names in the table of contents following refer to when the will was recorded. James Matthis Sr. of Halifax County, NC [mislabeled as Thomas Matthis Sr.] (1762) Joshua Stap of Northampton County, NC (1765) Thomas Davis of Halifax County, NC (1765) Thomas Mathis of Halifax County, NC (1765) Isaac Mathis of Halifax County, NC (1768) Thomas Matthews of Northampton County, NC (1770) Robert Read of Essex County, VA (1774) James Mathews of Halifax County, NC (1775) Charles Mathis of Chatham County, NC (1777) John Floyd of Northampton County, NC (1779) Hubbard Quarles of Brunswick County, VA (1780) Charles Mathis of Brunswick County, VA (1781) Reaps [Repps] Matthews of Halifax County, NC (1782) Luke (x) Matthews of Brunswick County, VA (1788) Arthur Davis of Halifax County, NC (1790) Susanna Mathews of Edgefield County, SC (1792) Drury Mathis of Brunswick County, VA (1795) William Pullen Sr. of Halifax County, NC (1795) Thomas Pace of Halifax County, NC (1795) Edmund Matthews (Mathis) of Hancock County, GA (1805) Ann Matthews of Halifax County, NC (1806) Clybron [Claiborne] Matthews of Chatham County, NC (1806) William Matthews of Halifax County, NC (1812) Jeremiah Mathews of Baldwin County, GA (1814) Gideon Mathews of Halifax County, NC (1815) Moses Matthews of Halifax County, NC (1815) James Mathews III of Morgan County, GA -

Plans for Station 1 Move Ahead Fate of Mathews Monument to Be Placed

GLOUCESTERMATHEWS THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 2020 VOL. LXXXIII, no. 37 NEW SERIES (USPS 220-560) GLOUCESTER, VA. 23061 | MATHEWS, VA. 23109 two sections 26 pages 75 CENTS Fate of Mathews monument to be placed on 2021 ballot BY CHARLIE KOENIG the Mathews County Board of ment would be moved to (if Supervisors decided it will pe- it is moved), the associated The fate of the Confederate tition the circuit court to have costs, whether there should monument in Mathews will be the matter placed on the No- be a plaque or marker to con- placed in the hands of county vember 2021 ballot. textualize the current monu- voters. Details of exactly what vot- ment—have yet to be worked By a 5-0 vote Wednesday ers will be asked to consid- night at Mathews High School, er—such as where the monu- SEE CONFEDERATE MONUMENT, PAGE 12A An architectural rendering presenting an aerial view of what the Gloucester Volunteer Fire and Rescue’s new Station 1 on Main Street is expected to look like after it is completed. Plans for Station 1 move ahead BY SHERRY HAMILTON plans, when completed by the front of the equipment bays Northern Virginia fi rm Hughes that will allow the ladder A new fi rehouse on Group Architects, will have truck to be parked in front Gloucester Main Street may some differences, but that the of the fi rehouse and not im- still be several years in the size and scope should remain pinge on Main Street, even making, but the plans are fairly consistent. -

Former Church Youth Leader Sentenced to 15 Years Borden Steps

GLOUCESTER-MATHEWS THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 13, 2020 VOL. LXXXIII, no. 7 NEW SERIES (USPS 220-560) GLOUCESTER, VA. 23061 | MATHEWS, VA. 23109 two sections 32 pages 75 CENTS Former church youth leader sentenced to 15 years BY SHERRY HAMILTON upon his release, will be pro- hibited from going within 100 Former church youth leader feet of any school or day care Kenneth Scott Marshall, 37, of center, playground, gymnasi- Marsh Hawk Road in Mathews um, athletic field, school bus, was sentenced to serve 15 or school-related activity. He years in prison by Judge Jef- is also prohibited from having frey W. Shaw during a hear- contact with the victim. He re- ing on Wednesday morning in quested an appeal. Mathews Circuit Court. Shaw Marshall was convicted by also imposed an additional a Williamsburg jury last Sep- three-year sentence under tember of one felony count of guidelines allowing for ad- forceful sodomy of a 15-year- ditional time in felony cases. old boy with an intellectual Those three years were sus- disability. The jury recom- pended. mended that he serve 15 Marshall was also ordered years in prison for the crime. to undergo psycho-sexual treatment while in prison and, SEE SCOTT MARSHALL, PAGE 17A Gloucester boards take look at supplementary use regulations BY MELANY SLAUGHTER and outdoor firing ranges CHARLIE KOENIG / GAZETTE-JOURNAL to outdoor uses pertaining In a joint meeting Tuesday to commercial and private Devils v Dukes night, Gloucester supervisors camping, hunting and fishing and planners took a look at a clubs and animal uses.