Trash Talk and Buried Treasure: Northcote and Hazlitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poets and Poetry of Scotland

THE POETS AND POETRY OF SCOTLAND. PERIOD 1777 TO 1876. THOMAS CAMPBELL Born 1777 — Died 1844. THOMAS CAMPBELL, so justly and himself of the instructions of the celebrated poetically called the "Bard of Hope," was Heyne, and attained such proficiency in Greek bom in High Street, Glasgow, July 27, 1777, and the classics generally that he was re- and was the youngest of a family of eleven garded as one of the best classical scholars of children. His father was connected with good his day. In speaking of his college career, families in Argyleshire, and had carried on a which was extended to five sessions, it is prosperous trade as a Virginian merchant, but worthy of notice that Professor Young, in met with heavy losses at the outbreak of the awarding to Campbell a prize for the best American war. The poet was particularly translation of the Clouds of Aristophanes, pro- fortunate in the. intellectual character of his nounced it to be the best exercise which had parents, his father being the intimate friend of ever been given in by any student belonging the celebrated Dr. Thomas Reid, author of the to the university. In original poetry he Inquiry into the. Human Mind, after whom he was also distinguished above all his class- received his Christian name, while his mother mates, so that in 1793 his "Poem on Descrip- was distinguished by her love of general litera- tion" obtained the prize in the logic class. ture, combined with sound understanding and Amongst his college companions Campbell a refined taste. Campbell afforded early indi- soon became known as a poet and wit; and on cations of genius; as a child he was fond of one occasion, the students having in vain made ballad poetry, and at the age of ten composed repeated application for a holiday' in commem- verses exhibiting the delicate appreciation of oration of some public event, he sent in a peti- the graceful flow and music of language for tion in verse, with which the professor was so which his poetry was afterwards so highly dis- pleased that the holiday was granted in com- tinguished. -

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C. Hunter Did Joshua Reynolds Paint His Pictures? The Transatlantic Work of Picturing in an Age of Chymical Reproduction In the spring of 1787, King George III visited the Royal Academy of Arts at Somerset House on the Strand in London’s West End. The king had come to see the first series of the Seven Sacraments painted by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) for Roman patron Cassiano dal Pozzo in the later 1630s. It was Poussin’s Extreme Unction (ca. 1638–1640) (fig. 1) that won the king’s particular praise.1 Below a coffered ceiling, Poussin depicts two trains of mourners converging in a darkened interior as a priest administers last rites to the dying man recumbent on a low bed. Light enters from the left in the elongated taper borne by a barefoot acolyte in a flowing, scarlet robe. It filters in peristaltic motion along the back wall where a projecting, circular molding describes somber totality. Ritual fluids proceed from the right, passing in relay from the cerulean pitcher on the illuminated tripod table to a green-garbed youth then to the gold flagon for which the central bearded elder reaches, to be rubbed as oily film on the invalid’s eyelids. Secured for twenty-first century eyes through a spectacular fund-raising campaign in 2013 by Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, Poussin’s picture had been put before the king in the 1780s by no less spirited means. Working for Charles Manners, fourth Duke of Rutland, a Scottish antiquarian named James Byres had Poussin’s Joshua Reynolds, Sacraments exported from Rome and shipped to London where they Diana (Sackville), Viscountess Crosbie were cleaned and exhibited under the auspices of Royal Academy (detail, see fig. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Prints from the Collection of the Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd Arts 3801 [Little Fatima.] [Painted by Frederick, Lord Leighton.] Gerald 2566 Robinson Crusoe Reading the Bible to Robinson. London Published December 15th 1898 by his Man Friday. "During the long timer Arthur Lucas the Proprietor, 31 New Bond Street, W. Mezzotint, proof signed by the engraver, ltd to 275. that Friday had now been with me, and 310 x 490mm. £420 that he began to speak to me, and 'Little Fatima' has an added interest because of its understand me. I was not wanting to lay a Orientalism. Leighton first showed an Oriental subject, foundation of religious knowledge in his a `Reminiscence of Algiers' at the Society of British mind _ He listened with great attention." Artists in 1858. Ten years later, in 1868, he made a Painted by Alexr. Fraser. Engraved by Charles G. journey to Egypt and in the autumn of 1873 he worked Lewis. London, Published Octr. 15, 1836 by Henry in Damascus where he made many studies and where Graves & Co., Printsellers to the King, 6 Pall Mall. he probably gained the inspiration for the present work. vignette of a shipwreck in margin below image. Gerald Philip Robinson (printmaker; 1858 - Mixed-method, mezzotint with remarques showing the 1942)Mostly declared pirnts PSA. wreck of his ship. 640 x 515mm. Tears in bottom Printsellers:Vol.II: margins affecting the plate mark. -

Friendship and the Art of Listening: the Conversations of James Boswell and Samuel Johnson in William Hazlitt’S Essays

Friendship and the art of listening: the conversations of James Boswell and Samuel Johnson in William Hazlitt’s essays. It has been said that the art of conversation is one of 18th century’s major legacies. Such an art is at the centre of that refined form of sociability which has never in history been so fully developed, whether in cafés, clubs or salons; through which the meanest subjects were examined and put to test, whereas intricate ones were dipped in new, interesting and surprising colours, never leaden or tiresome. Through which, philosophy dressed the garb of literature; poetry and literary prose, philosophical lineaments. In a word, the esprit géometrique and the esprit de finesse have never been so inwardly intertwined. It was in the 18th century, for example, that the epistolary novel best flourished. And what is a letter but distance conversation in which intimacies are confided to the reader, as to an old friend, and any topic is quarrelled in a familiar tone? According to William Hazlitt, Lawrence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, one of the century’s most popular novels, “is the pure essence of English conversational style” (5, 110)1. While engaged in its reading, continues the critic, “you fancy that you hear people talking” (8, 36). After the king George II bestowed on Samuel Johnson a life pension for what he had done, The Dictionary of English Language, he committed himself to his most beloved art and one which few has ever practiced with equal freedom: conversation. Though hard-faced, good-humour is the tone to most of his “table-talks”2, and because Johnson was never blinded by stingy prejudices, he heartily welcomed the libertine Boswell. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

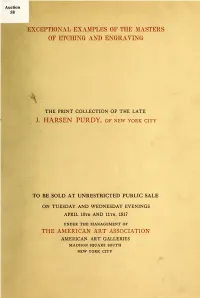

Exceptional Examples of the Masters of Etching and Engraving : the Print Collection of the Late J. Harsen Purdy, of New York

EXCEPTIONAL EXAMPLES OF THE MASTERS OF ETCHINa AND ENGRAVING THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE SOLD AT UNRESTRICTED PUBLIC SALE ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY EVENINGS APRIL 10th and 11th, 1917 UNDER THE MANAGEMENT OF THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH NEW YORK CITY smithsoniaM INSTITUTION 3i< 7' THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION DESIGNS ITS CATALOGUES AND DIRECTS ALL DETAILS OF ILLUSTRATION TEXT AND TYPOGRAPHY ON PUBLIC EXHIBITION AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK ENTRANCE, 6 EAST 23rd STREET BEGINNING THURSDAY, APRIL 5th, 1917 MASTERPIECES OF ENGRAVERS AND ETCHERS THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE SOLD AT UNRESTRICTED PUBLIC SALE BY ORDER OF ALBERT W. PROSS, ESQ., AND THE NEW YORK TRUST COMPANY, AS EXECUTORS ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY EVENINGS APRIL 10th and 11th, 1917 AT 8:00 O'CLOCK IN THE EVENINGS AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES ALBRECHT DURER, ENGRAVING Knight, Death and the Devil [No. 69] EXCEPTIONAL EXAMPLES OF THE MASTERS OF ETCHING AND ENGRAVING THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE sold at unrestricted PUBLIC SALE BY ORDER OF ALBERT W. PROSS, ESQ., AND THE NEW YORK TRUST COMPANY, AS EXECUTORS ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY, APRIL 10th AND 11th AT 8:00 O'CLOCK IN THE EVENINGS THE SALE TO BE CONDUCTED BY MR. THOMAS E. KIRBY AND HIS ASSISTANTS, OF THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION, Managers NEW YORK CITY 1917 ——— ^37 INTRODUCTORY NOTICE REGARDING THE PRINT- COLLECTION OF THE LATE MR. -

Grosvenor Prints Catalogue

Grosvenor Prints Tel: 020 7836 1979 19 Shelton Street [email protected] Covent Garden www.grosvenorprints.com London WC2H 9JN Catalogue 110 Item 50. ` Cover: Detail of item 179 Back: Detail of Item 288 Registered in England No. 305630 Registered Office: 2, Castle Business Village, Station Road, Hampton, Middlesex. TW12 2BX. Rainbrook Ltd. Directors: N.C. Talbot. T.D.M. Rainment. C.E. Ellis. E&OE VAT No. 217 6907 49 1. [A country lane] A full length female figure, etched by Eugene Gaujean P.S. Munn. 1810. (1850-1900) after a design for a tapestry by Sir Edward Lithograph. Sheet 235 x 365mm (9¼ x Coley Burne-Jones (1833-98) for William Morris. PSA 14¼")watermarked 'J Whatman 1808'. Ink smear. £90 275 signed proof. Early lithograph, depicting a lane winding through Stock: 56456 fields and trees. Paul Sandby Munn (1773-1845), named after his godfather, Paul Sandby, who gave him his first instructions in watercolour painting. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1798 and was a frequent contributor of topographical drawings to that and other exhibtions. Stock: 56472 2. [A water mill] P.S. Munn. [n.d., c.1810.] Lithograph. Sheet 235 x 365mm (9¼ x 14¼"), watermarked 'J Whatman 1808'. Creases £140 Early pen lithograph, depicting a delapidated cottage with a mill wheel. Paul Sandby Munn (1773-1845), named after his godfather, Paul Sandby, who gave him his first instructions in watercolour painting. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1798 and was a frequent contributor of topographical drawings to that and other exhibtions. -

Florida Historical Quarterly

COVER British East Florida reached from the St. Marys River on the north to the Apalachicola River on the west and its capital stood at St. Augustine. The province of West Florida extended westward to the Mississippi River and to the thirty-first parallel on the north (and after 1764 to thirty-two degrees twenty-eight minutes). Pensacola served as its capital. Guillaume Delisle published his “Carte du Mexique et de la Floride des Terres Angloises et des Isles Antilles du Cours et des Environs de la Rivière de Mississippi,” in his Atlas Nouveau, vol. 2, no. 29 (Amsterdam, 1741[?]). The map first appeared in Paris in 1703. This portion of the map is repro- duced from a copy (1722 PKY 76) in the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida His- tory, University of Florida, Gainesville. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Volume LIV, Number 4 April 1976 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY SAMUEL PROCTOR, Editor STEPHEN KERBER, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD LUIS R. ARANA Castillo de San Marcos, St. Augustine HERBERT J. DOHERTY, JR. University of Florida JOHN K. MAHON University of Florida WILLIAM W. ROGERS Florida State University JERRELL H. SHOFNER Florida Technological University CHARLTON W. TEBEAU University of Miami Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, original- ity of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and interest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. -

Chester County Deed Book Index 1681-1865

Chester County Deed Book Index 1681-1865 Buyer/Seller Last First Middle Sfx/Pfx Spouse Residence Misc Property Location Village/Tract Other Party Year Book Page Instrument Comments Seller (Grantor) Cabber Charles East Brandywine Dec'd East Brandywine William Coyle 1858 K-6 116 Deed Seller (Grantor) Cadbury Joel Caroline W. Philadelphia New Garden Chandlerville Samuel Comly 1840 T-4 177 Deed Factory Seller (Grantor) Cadbury Joel Caroline W. Philadelphia Honey Brook John Cochran 1848 P-5 475 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Cadwalader Charles East Caln West Caln William Neally 1786 A-2 301 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Cadwalader Isaac Uwchlan Uwchlan Mary Norris 1791 F-2 325 Covenant Seller (Grantor) Cadwalader Isaac Sr. Sarah Uwchlan Uwchlan Isaac Cadwalader 1814 L-3 129 Deed Seller (Grantor) Cadwalader Isaac Sr. Sarah Uwchlan Uwchlan Isaac Thomas 1814 I-3 471 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Cadwalader Isaac Sr. Uwchlan Uwchlan Isaac Thomas 1814 M-3 438 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Cadwalader Isaac Jr. Uwchlan Uwchlan Isaac Cadwalader 1814 L-3 129 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Cadwalader Isaac Warwick Warwick Jesse Houck 1853 U-5 83 Deed Seller (Grantor) Cadwalader Isaac P. Susanna Warwick Warwick Abram Sivert 1860 P-6 232 Deed Seller (Grantor) Cadwalader John Sarah Uwchlan Uwchlan Joseph Phipps 1719 T-2 121 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Cadwalader John Newlin Newlin Isaac H. Bailey 1846 D-5 299 Deed Chester County Archives and Record Services, West Chester, PA 19380 Chester County Deed Book Index 1681-1865 Buyer/Seller Last First Middle Sfx/Pfx Spouse Residence Misc Property Location Village/Tract Other Party Year Book Page Instrument Comments Seller (Grantor) Cadwalader John Jane Newlin East Marlborough Marlborough John Huey Jr. -

Hester Thrale Piozzi's Annotated Copy of James Northcote's Biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds

"Well said Mr. Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's annotated copy of James Northcote's biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wendorf, Richard. 2000. "Well said Mr. Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's annotated copy of James Northcote's biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Harvard Library Bulletin 9 (4), Winter 1998: 29-40. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37363299 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 29 "Well said M~ Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's Annotated Copy of James Northcote's Biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds Richard Wendoif ester Lynch Thrale Piozzi was of two minds about Sir Joshua RICHARD WENDORF is the Reynolds. She greatly admired him as a painter-or at least as a Stanford Calderwood H painter of portraits. When he attempted to soar beyond portraiture Director and Librarian of into the realm of history painting, she found him to be embarrassingly the Boston Athena:um. out of his depth. Reynolds professed "the Sublime of Painting I think," she wrote in her voluminous commonplace book, "with the same Affectation as Gray does in Poetry, both of them tame quiet Characters by Nature, but forced into Fire by Artifice & Effort." 1 As a portrait-painter, however, Reynolds impressed her as having no equal, and she took great pride in his series of portraits commissioned by her first husband, Henry Thrale, for the library at their house in Streatham. -

The Hazlitt Review

THE HAZLITT REVIEW The Hazlitt Review is an annual peer-reviewed journal, the first internationally to be devoted to Hazlitt studies. The Review aims to promote and maintain Hazlitt’s standing, both in the academy and to a wider readership, by providing a forum for new writing on Hazlitt, by established scholars as well as more recent entrants in the field. Editor Uttara Natarajan Assistant Editors James Whitehead, Phillip Hunnekuhl Editorial Board Geoffrey Bindman James Mulvihill David Bromwich Tom Paulin Jon Cook Seamus Perry Gregory Dart Michael Simpson A.C. Grayling Fiona Stafford Paul Hamilton Graeme Stones Ian Mayes John Whale Tim Milnes Duncan Wu We invite essays of 4,000 to 9,000 words in length on any aspect of William Hazlitt’s work and life; articles relating Hazlitt to wider Romantic circles, topics, or discourses are also expressly welcome, as are reviews of books pertaining to such matters. Contributions should follow the MHRA style and should be sent by email to James Whitehead ([email protected]) or Philipp Hunnekuhl ([email protected]). Submissions will be considered year- round, but must be received by 1 March to be considered for publication in the same year’s Review. We regret that we cannot publish material already published or submitted elsewhere. Contributors who require their articles to be open access (under the RCUK policy effective from the 1 April 2013) should indicate this, and they will be made freely available on this website on publication. Subscriptions, including annual membership of the Hazlitt Society, are £10 (individual) or £15 (corporate or institution) per annum.