Of Dr. John Huxham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finishing Off Joseph Van Aken

In-Focus Finishing Off Joseph van Aken Britain’s Leading Drapery Painter Joseph van Aken Going it Alone IMAGES NOT AVAILABLE In The London Tradesman (1747), a On van Aken’s death in 1749 his handbook of professions, the drapery brother Alexander, a lesser artist, tried painter is listed as a ‘mere mechanic to continue this family business, but hand’ who is ‘employed in dressing the the smooth running of several portrait figures, after the painter has finished painters’ studios was disrupted for the face, given the figure its proper months. No single drapery painter attitude, and drawn the out-lines of the Van Aken’s drapery may be one reason ever again achieved van Aken’s hold dress or drapery.’ This may have been why many portraits from the 1740s, over the market, and the practice of true for many anonymous hacks, but look so similar. Surviving drawings outsourcing drapery slowly dwindled. the Flemish-born artist Joseph van Aken suggest that Ramsay provided detailed By the 1760s and’70s, artists such (c.1699–1749) earned great wealth instructions about howvan Aken should as Thomas Gainsborough or Joseph as Britain’s leading drapery painter. pose and dress his figures. Others Wright of Derby were painting all parts He worked for Thomas Hudson, Allan merely supplied the face – sometimes of their canvases themselves. Ramsay, Joseph Highmore and so cut out and tacked to a larger canvas. many other successful portrait painters Such was the consistent quality of van Thomas Day (1748–89) of the 1740s that one critic remarked, Aken’s ‘draperies, silks, satins, velvets’ by Joseph Wright of Derby, 1770 NPG 2490 acidly: ‘As in England almost that artists found it a ‘great addition to everybody’s picture is painted, so their works and .. -

Darnley Portraits

DARNLEY FINE ART DARNLEY FINE ART PresentingPresenting anan Exhibition of of Portraits for Sale Portraits for Sale EXHIBITING A SELECTION OF PORTRAITS FOR SALE DATING FROM THE MID 16TH TO EARLY 19TH CENTURY On view for sale at 18 Milner Street CHELSEA, London, SW3 2PU tel: +44 (0) 1932 976206 www.darnleyfineart.com 3 4 CONTENTS Artist Title English School, (Mid 16th C.) Captain John Hyfield English School (Late 16th C.) A Merchant English School, (Early 17th C.) A Melancholic Gentleman English School, (Early 17th C.) A Lady Wearing a Garland of Roses Continental School, (Early 17th C.) A Gentleman with a Crossbow Winder Flemish School, (Early 17th C.) A Boy in a Black Tunic Gilbert Jackson A Girl Cornelius Johnson A Gentleman in a Slashed Black Doublet English School, (Mid 17th C.) A Naval Officer Mary Beale A Gentleman Circle of Mary Beale, Late 17th C.) A Gentleman Continental School, (Early 19th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Gerard van Honthorst, (Mid 17th C.) A Gentleman in Armour Circle of Pieter Harmensz Verelst, (Late 17th C.) A Young Man Hendrick van Somer St. Jerome Jacob Huysmans A Lady by a Fountain After Sir Peter Paul Rubens, (Late 17th C.) Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel After Sir Peter Lely, (Late 17th C.) The Duke and Duchess of York After Hans Holbein the Younger, (Early 17th to Mid 18th C.) William Warham Follower of Sir Godfrey Kneller, (Early 18th C.) Head of a Gentleman English School, (Mid 18th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Hycinthe Rigaud, (Early 18th C.) A Gentleman in a Fur Hat Arthur Pond A Gentleman in a Blue Coat -

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C. Hunter Did Joshua Reynolds Paint His Pictures? The Transatlantic Work of Picturing in an Age of Chymical Reproduction In the spring of 1787, King George III visited the Royal Academy of Arts at Somerset House on the Strand in London’s West End. The king had come to see the first series of the Seven Sacraments painted by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) for Roman patron Cassiano dal Pozzo in the later 1630s. It was Poussin’s Extreme Unction (ca. 1638–1640) (fig. 1) that won the king’s particular praise.1 Below a coffered ceiling, Poussin depicts two trains of mourners converging in a darkened interior as a priest administers last rites to the dying man recumbent on a low bed. Light enters from the left in the elongated taper borne by a barefoot acolyte in a flowing, scarlet robe. It filters in peristaltic motion along the back wall where a projecting, circular molding describes somber totality. Ritual fluids proceed from the right, passing in relay from the cerulean pitcher on the illuminated tripod table to a green-garbed youth then to the gold flagon for which the central bearded elder reaches, to be rubbed as oily film on the invalid’s eyelids. Secured for twenty-first century eyes through a spectacular fund-raising campaign in 2013 by Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, Poussin’s picture had been put before the king in the 1780s by no less spirited means. Working for Charles Manners, fourth Duke of Rutland, a Scottish antiquarian named James Byres had Poussin’s Joshua Reynolds, Sacraments exported from Rome and shipped to London where they Diana (Sackville), Viscountess Crosbie were cleaned and exhibited under the auspices of Royal Academy (detail, see fig. -

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Prints from the Collection of the Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd Arts 3801 [Little Fatima.] [Painted by Frederick, Lord Leighton.] Gerald 2566 Robinson Crusoe Reading the Bible to Robinson. London Published December 15th 1898 by his Man Friday. "During the long timer Arthur Lucas the Proprietor, 31 New Bond Street, W. Mezzotint, proof signed by the engraver, ltd to 275. that Friday had now been with me, and 310 x 490mm. £420 that he began to speak to me, and 'Little Fatima' has an added interest because of its understand me. I was not wanting to lay a Orientalism. Leighton first showed an Oriental subject, foundation of religious knowledge in his a `Reminiscence of Algiers' at the Society of British mind _ He listened with great attention." Artists in 1858. Ten years later, in 1868, he made a Painted by Alexr. Fraser. Engraved by Charles G. journey to Egypt and in the autumn of 1873 he worked Lewis. London, Published Octr. 15, 1836 by Henry in Damascus where he made many studies and where Graves & Co., Printsellers to the King, 6 Pall Mall. he probably gained the inspiration for the present work. vignette of a shipwreck in margin below image. Gerald Philip Robinson (printmaker; 1858 - Mixed-method, mezzotint with remarques showing the 1942)Mostly declared pirnts PSA. wreck of his ship. 640 x 515mm. Tears in bottom Printsellers:Vol.II: margins affecting the plate mark. -

Friendship and the Art of Listening: the Conversations of James Boswell and Samuel Johnson in William Hazlitt’S Essays

Friendship and the art of listening: the conversations of James Boswell and Samuel Johnson in William Hazlitt’s essays. It has been said that the art of conversation is one of 18th century’s major legacies. Such an art is at the centre of that refined form of sociability which has never in history been so fully developed, whether in cafés, clubs or salons; through which the meanest subjects were examined and put to test, whereas intricate ones were dipped in new, interesting and surprising colours, never leaden or tiresome. Through which, philosophy dressed the garb of literature; poetry and literary prose, philosophical lineaments. In a word, the esprit géometrique and the esprit de finesse have never been so inwardly intertwined. It was in the 18th century, for example, that the epistolary novel best flourished. And what is a letter but distance conversation in which intimacies are confided to the reader, as to an old friend, and any topic is quarrelled in a familiar tone? According to William Hazlitt, Lawrence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, one of the century’s most popular novels, “is the pure essence of English conversational style” (5, 110)1. While engaged in its reading, continues the critic, “you fancy that you hear people talking” (8, 36). After the king George II bestowed on Samuel Johnson a life pension for what he had done, The Dictionary of English Language, he committed himself to his most beloved art and one which few has ever practiced with equal freedom: conversation. Though hard-faced, good-humour is the tone to most of his “table-talks”2, and because Johnson was never blinded by stingy prejudices, he heartily welcomed the libertine Boswell. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

Portela, Manuel (2004), 'A Portrait of the Author As an Author'

Pre-print version To cite this Article: Portela, Manuel (2004), ‘A Portrait of the Author as an Author’, Novas Histórias Literárias/New Literary Histories, Coimbra: CoimbraMinerva, pp. 357-371. Manuel Portela A PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR AS AN AUTHOR Abstract The growth of the literary market in the eighteenth century changed concepts of authorship. Portrait conventions were also used to frame authorial personality. By looking at pictorial representations of men and women authors, in paintings and prints, I identify conflicting images of authorship. Idealised representations of the author as gentleman or lady are contrasted with images of the violence of market forces. Polite restraint of the self-conscious individual genius has to face the unruly passions and interests that characterise the new social relations of literary production.1 Resumo O crescimento do mercado literário no século XVIII alterou a concepção da autoria. As convenções do retrato foram também usadas para definir a personalidade autoral. Através da observação de representações de autores e autoras, em pinturas e gravuras, identifico imagens contraditórias da autoria. Representações idealizadas do autor enquanto cavalheiro ou enquanto senhora são contrastadas com imagens da violência das forças do mercado. O autodomínio polido do génio individual tem de enfrentar as paixões e interesses desregrados que caracterizam as novas relações sociais de produção. Keywords: portrait painting; literary authorship; Jonathan Richardson; William Hogarth; Grub-street. 1 Most URLs in this article link to the online catalogue of the National Portrait Gallery, London. They have been updated in December 2011, when this file was added to the online repository of the University of Coimbra. -

Hester Thrale Piozzi's Annotated Copy of James Northcote's Biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds

"Well said Mr. Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's annotated copy of James Northcote's biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wendorf, Richard. 2000. "Well said Mr. Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's annotated copy of James Northcote's biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Harvard Library Bulletin 9 (4), Winter 1998: 29-40. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37363299 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 29 "Well said M~ Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's Annotated Copy of James Northcote's Biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds Richard Wendoif ester Lynch Thrale Piozzi was of two minds about Sir Joshua RICHARD WENDORF is the Reynolds. She greatly admired him as a painter-or at least as a Stanford Calderwood H painter of portraits. When he attempted to soar beyond portraiture Director and Librarian of into the realm of history painting, she found him to be embarrassingly the Boston Athena:um. out of his depth. Reynolds professed "the Sublime of Painting I think," she wrote in her voluminous commonplace book, "with the same Affectation as Gray does in Poetry, both of them tame quiet Characters by Nature, but forced into Fire by Artifice & Effort." 1 As a portrait-painter, however, Reynolds impressed her as having no equal, and she took great pride in his series of portraits commissioned by her first husband, Henry Thrale, for the library at their house in Streatham. -

The Summer Exhibition 3

ART HISTORY REVEALED Dr. Laurence Shafe This course is an eclectic wander through art history. It consists of twenty two-hour talks starting in September 2018 and the topics are largely taken from exhibitions held in London during 2018. The aim is not to provide a guide to the exhibition but to use it as a starting point to discuss the topics raised and to show the major art works. An exhibition often contains 100 to 200 art works but in each two-hour talk I will focus on the 20 to 30 major works and I will often add works not shown in the exhibition to illustrate a point. References and Copyright • The talks are given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • The notes are based on information found on the public websites of Wikipedia, Tate, National Gallery, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story. • If a talk uses information from specific books, websites or articles these are referenced at the beginning of each talk and in the ‘References’ section of the relevant page. The talks that are based on an exhibition use the booklets and book associated with the exhibition. • Where possible images and information are taken from Wikipedia under 1 an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 ART HISTORY REVEALED 1. Impressionism in London 1. -

The Cunning of Sir Sloshua: Reynolds, the Sea, and Risk

P.C. Canot after George Lambert and Samuel Scott. A View of Mount Edgcumbe Taken from St Nicholas’s Island , 1755. Etching and engraving. 80 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00229 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00229 by guest on 01 October 2021 The Cunning of Sir Sloshua: Reynolds, the Sea, and Risk MATTHEW C. HUNTER In 1743, Joshua Reynolds broke the terms of his apprenticeship to London painter Thomas Hudson and returned to his native county of Devon. Plying a trade in portraits to an officer class at the major naval base in Plymouth, Reynolds (1723–1792) lived in the newly built Plymouth Dock, a site Daniel Defoe had recently described “as complete an Arsenal, or Yard, for building and fitting out Men of War, as any the Government are Masters of.” 1 It was there that Reynolds established connections to a local elite that would ensure his fortunes. As his pupil James Northcote subsequently told it, “During his residence at Plymouth he first became known to the family of Mount Edgcumbe; who warmly patronized him, and not only employed him in his profession, but also strongly recommended him to the Honourable Augustus Keppel, then a captain in the navy.” 2 Visible across Plymouth sound at left hand in P.C. Canot’s etching and engraving of 1755, the imperious prospect of Mount Edgcumbe was commanded by Richard, first Baron Edgcumbe, an operative in the Whig political machine of Prime Minister Robert Walpole. 3 A political fixer, Edgcumbe brokered Reynolds’s introduction to Augustus Keppel, captain of HMS Centurion . -

Robert Adam's Revolution in Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hausberg, Miranda Jane Routh, "Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3339. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Abstract ABSTRACT ROBERT ADAM’S REVOLUTION IN ARCHITECTURE Robert Adam (1728-92) was a revolutionary artist and, unusually, he possessed the insight and bravado to self-identify as one publicly. In the first fascicle of his three-volume Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (published in installments between 1773 and 1822), he proclaimed that he had started a “revolution” in the art of architecture. Adam’s “revolution” was expansive: it comprised the introduction of avant-garde, light, and elegant architectural decoration; mastery in the design of picturesque and scenographic interiors; and a revision of Renaissance traditions, including the relegation of architectural orders, the rejection of most Palladian forms, and the embrace of the concept of taste as a foundation of architecture. -

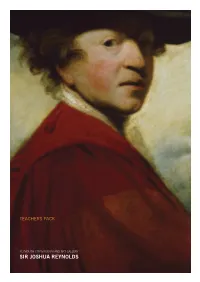

Sir Joshua Reynolds Contents

TEACHERS PACK PLYMOUTH CITY MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS CONTENTS Who was Sir Joshua Reynolds? 3 The 18th Century 4 The Royal Academy 6 Reynolds and Celebrity 7 Portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds 8-17 3 WHO WAS SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS? Sir Joshua Reynolds was born in Plympton In May 1749, aged 26, Reynolds travelled on 15 July 1723. His father Samuel Reynolds to Italy with Captain Augustus Keppel, and was a clergyman, and Master of Plympton for the first time saw works by the great Grammar School, which later became Hele’s Italian painters, which were to become the School. Reynolds’ passion for art was clear inspiration for many of his later paintings. from his childhood. At the age of nineteen, He stayed in Rome for two years, making he began to study painting with the London- detailed copies of work by the masters that based artist Thomas Hudson, who was inspired him. He travelled to Florence for six himself a successful portrait painter. After months, Venice for six weeks, and Bologna learning how to paint portraits that flattered and Palma for a few days. his subjects, he returned to Plymouth Dock In 1753, Reynolds returned home to Devon. and began to paint portraits of well-off local After three months he moved to London and people and their families. set up a studio at St Martin’s Lane. His rise In terms of his career opportunities, in popularity amongst London’s wealthy elite Plymouth Dock was an important area secured 125 sitters in 1755 alone. This led for Reynolds to have relocated.