Active and Intelligent Packaging: Innovations for the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mt Handbook 0.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1. Status, market size and scope of fruit and vegetable processing 4 industry in India 1.2. Selection and procurement 5 1.3. Supply chain of fruits and vegetables 15 1.4. Pack house handling of fruits and vegetables 19 1.5. Primary Processing of Fruits and Vegetables 26 1.6. Unit operations in fruits and vegetables processing 30 1.7. Minimal Processing of Fruits and Vegetables 42 Chapter 2: Value addition of Fruits and Vegetables 2.1. Processing of fruit pulp/puree 49 2.2. Processing of Jams 50 2.3. Processing of Jellies 54 2.4. Processing of osmotic dehydrated product 59 2.5. Preservation by chemicals 63 2.6. Processing of Sauce 65 2.7. Processing of Ketchup 67 2.8. Processing of Pickles 73 2.9. Processing of Chutneys 80 2.10. Processing of Fruit Juices 82 Chapter 3: Packaging of Fruits and Vegetable Products 3.1. Levels, functions and desirable features of packaging 93 3.2. Packaging materials and their properties 95 3.3. Special Packaging systems 112 3.4. Properties/characteristics of foods, packaging requirement and 115 methods 3.5. MAP of fruits and vegetables 116 3.6. Mechanical injuries of fruits and vegetables 118 3.7. Shelf life of packaged food and its determination 121 3.8. Storage of Fruits and Vegetables 124 Chapter 4: Food safety regulations & certification 4.1. Need for testing of food 130 4.2. List of Notified Reference Laboratories in India – 1 131 4.3. List of Notified Reference Laboratories in India – 2 132 4.4. -

Packaging Food and Dairy Products for Extended Shelf-Life Active Packaging: Films and Coatings for Ex- 426 Shelf Life, ESL Milk and Case-Ready Meat

Packaging Food and Dairy Products for Extended Shelf-Life Active packaging: Films and coatings for ex- 426 shelf life, ESL milk and case-ready meat. In the last two years, there tended shelf life. Paul Dawson*, Clemson University. has been substantial growth in extended shelf life milk packaged in sin- gle serve PET or HDPE containers. The combination of ESL processing Shelf life encompasses both safety and quality of food. Safety and and a plastic container results in an extended shelf life of 60 to 90 days, spoilage-related changes in food occur by three modes of action; bi- and at the same time provides consumers with the attributes they are ological (bacterial/enzymatic), chemical (autoxidation/pigments), and demanding from the package: convenience, portability, and resealabil- physical. Active packaging may intervene in the deteriorative reactions ity. The second example of how polymers are part of the solution to by; altering the package film permeability, selectively absorbing food extend shelf life is focused on case-ready beef. Here, a combination of components or releasing compounds to the food. The focus of this re- a polymer with the appropriate gas barrier and a modified atmosphere port will consider research covering impregnated packaging films that re- allows beef to retain its bright red color longer, extending its shelf life. lease compounds to extend shelf life. The addition of shelf life extending Plastics are increasingly used in food packaging and will be part of the compounds to packaging films rather than directly to food can be used future of extended shelf life products. to provide continued inhibition for product stabilization. -

4 Active Packaging in Polymer Films M.L

4 Active packaging in polymer films M.L. ROONEY 4.1 Introduction Polymers constitute either all or part of most primary packages for foods and beverages and a great deal of research has been devoted to the introduction of active packaging processes into plastics. Plastics are thermoplastic polymers containing additional components such as antioxidants and processing aids. Most forms of active packaging involve an intimate interaction between the food and its package so it is the layer closest to the food that is often chosen to be active. Thus polymer films potentially constitute the position of choice for incorporation of ingredients that are active chemically or physically. These polymer films might be used as closure wads, lacquers or enamels in cans and as the waterproof layer in liquid cartonboard, or as packages in their own right. The commercial development of active packaging plastics has not occurred evenly across the range of possible applications. Physical processes such as microwave heating by use of susceptor films and the generation of an equilibrium modified atmosphere (EMA) by modification of plastics films have been available for several years. Research continues to be popular in both these areas. Chemical processes such as oxygen scavenging have been adopted more rapidly in sachet form rather than in plastics. Oxygen scavenging sachets were introduced to the Japanese market in 1978 (Abe and Kondoh, 1989) whereas the first oxygen-scavenging beer bottle closures were used in 1989 (see Chapter 8). The development of plastics active packaging systems has been more closely tied to the requirements of particular food types or food processes than has sachet development. -

No 1333/2008 of the EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT and of the COUNCIL of 16 December 2008 on Food Additives (Text with EEA Relevance)

2008R1333 — EN — 21.04.2015 — 022.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B REGULATION (EC) No 1333/2008 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 16 December 2008 on food additives (Text with EEA relevance) (OJ L 354, 31.12.2008, p. 16) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EU) No 238/2010 of 22 March 2010 L 75 17 23.3.2010 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1129/2011 of 11 November 2011 L 295 1 12.11.2011 ►M3 amended by Commission Regulation (EU) No 1152/2013 of 19 L 311 1 20.11.2013 November 2013 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1130/2011 of 11 November 2011 L 295 178 12.11.2011 ►M5 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1131/2011 of 11 November 2011 L 295 205 12.11.2011 ►M6 Commission Regulation (EU) No 232/2012 of 16 March 2012 L 78 1 17.3.2012 ►M7 Commission Regulation (EU) No 380/2012 of 3 May 2012 L 119 14 4.5.2012 ►M8 Commission Regulation (EU) No 470/2012 of 4 June 2012 L 144 16 5.6.2012 ►M9 Commission Regulation (EU) No 471/2012 of 4 June 2012 L 144 19 5.6.2012 ►M10 Commission Regulation (EU) No 472/2012 of 4 June 2012 L 144 22 5.6.2012 ►M11 Commission Regulation (EU) No 570/2012 of 28 June 2012 L 169 43 29.6.2012 ►M12 Commission Regulation (EU) No 583/2012 of 2 July 2012 L 173 8 3.7.2012 ►M13 Commission Regulation (EU) No 675/2012 of 23 July 2012 L 196 52 24.7.2012 ►M14 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1049/2012 of 8 November 2012 L 310 41 9.11.2012 ►M15 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1057/2012 of 12 November 2012 -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Oxygen-Reducing Enzymes in Coatings and Films for Active Packaging |

Kristin Johansson | Oxygen-reducing enzymes in coatings and films for active packaging | | Oxygen-reducing enzymes in coatings and films for active packaging Kristin Johansson Oxygen-reducing enzymes in coatings and films for active packaging Oxygen-reducing enzymes This work focused on investigating the possibility to produce oxygen-scavenging packaging materials based on oxygen-reducing enzymes. The enzymes were incorporated into a dispersion coating formulation applied onto a food- in coatings and films for packaging board using conventional laboratory coating techniques. The oxygen- reducing enzymes investigated included a glucose oxidase, an oxalate oxidase active packaging and three laccases originating from different organisms. All of the enzymes were successfully incorporated into a coating layer and could be reactivated after drying. For at least two of the enzymes, re-activation after drying was possible not only Kristin Johansson by using liquid water but also by using water vapour. Re-activation of the glucose oxidase and a laccase required relative humidities of greater than 75% and greater than 92%, respectively. Catalytic reduction of oxygen gas by glucose oxidase was promoted by creating 2013:38 an open structure through addition of clay to the coating formulation at a level above the critical pigment volume concentration. For laccase-catalysed reduction of oxygen gas, it was possible to use lignin derivatives as substrates for the enzymatic reaction. At 7°C all three laccases retained more than 20% of the activity they -

Active and Intelligent Packaging

Paper No.: 12 Paper Title: FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Module – 25: Active and Intelligent Packaging 1. Introduction: For a long time packaging also had an active role in processing and preservation of quality of foods. Variations in the way food products are produced, circulated, stored and sold, reflecting the continuing increase in consumer demand for improved safety, quality and shelf- life for packaged foods are assigning greater demands on the performance of food packaging. Consumers want to be assured that the packaging is fulfilling its function of protecting the quality, freshness and safety of foods. Thus, advances in food packaging are both anticipated and expected. Society is becoming increasingly complex and innovative packaging is the outcome of consumers' demand for packaging that is more advanced and creative than what is currently offered. “Active packaging” and “intelligent packaging” are the result of innovating thinking in packaging. Active packaging can be defined as “Packaging in which supplementary constituents have been deliberately added in or on either the packaging material of the package headspace to improve the performance of the package system”. In simple terms, Active packaging is an extension of the protection purpose of a package and is commonly used to protect against oxygen and moisture. It permits packages to interact with food and environment. Thus, play a dynamic role in food preservation. Developments in active packaging have led to advances in many areas, like delayed oxidation and controlled respiration rate, microbial growth and moisture migration. Other active packaging technologies include carbon dioxide absorbers/emitters, odour absorbers, ethylene removers, and aroma emitters. On the other hand, intelligent packing can be defined as “Packaging that has an external or internal indicator to provide information about characteristics of the history of the package and/or the quality of the food packed”. -

Chapter 1: Introduction

ZAZ 0701 Finding Green Solutions for Nypro, Inc A Major Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By ________________________ Emily Allietta ________________________ Catherine Maki Date: March 4, 2008 Approved: __________________________________ Professor Amy Zeng, Primary Advisor 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................ 2 Table of Figures .................................................................................................................. 4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 6 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 7 2 Literature Review........................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Purchasing Strategies .............................................................................................. 10 2.2 Energy and Gas ....................................................................................................... 11 2.2.1 Gas Trends ...................................................................................................... -

RANGE GUIDE Johnlewis.Com Kitchen KBRG/08.18

Shop locations Autumn 2018 LONDON John Lewis Cribbs Causeway John Lewis Sheffield The Mall at Cribbs Causeway Barkers Pool John Lewis Bristol BS34 5QU Sheffield S1 1EP Oxford Street 0117 959 1100 0114 276 8511 London W1A 1EX 020 7629 7711 John Lewis High Wycombe John Lewis Solihull Holmers Farm Way Touchwood Peter Jones Cressex Solihull Sloane Square High Wycombe HP12 4NW West Midlands B91 3RA London SW1W 8EL 01494 462 666 0121 704 1121 020 7730 3434 John Lewis Leeds John Lewis Southampton John Lewis Brent Cross Victoria Gate West Quay Brent Cross Shopping Centre Harewood Street Southampton SO15 1QA London NW4 3FL Leeds S2 7AR 023 8021 6400 020 8202 6535 0113 394 6200 John Lewis Watford John Lewis Kingston John Lewis Leicester High Street Wood Street 2 Bath House Lane Watford WD17 2TW Kingston upon Thames Highcross Shopping Centre 01923 244 266 KT1 1TE Leicester LE1 4SA 020 8547 3000 0116 242 5777 John Lewis Welwyn Bridge Road John Lewis Stratford John Lewis Liverpool Welwyn Garden City 101 The Arcade 70 South John Street AL8 6TP Westfield Stratford City Liverpool One 01707 323 456 Montfichet Road Liverpool L1 8BJ London E20 1EL 0151 709 7070 John Lewis York 020 8532 3500 Unit C John Lewis Milton Keynes Vangarde Way John Lewis White City Central Milton Keynes York YO32 9AE Westfield London MK9 3EP 01904 557 950 Shopping Centre 01908 679 171 Ariel Way SCOTLAND London W12 7FU John Lewis Newcastle 020 8222 6400 Eldon Square John Lewis Aberdeen Newcastle upon Tyne George Street ENGLAND NE99 1AB Aberdeen AB25 1BW 0191 232 5000 01224 625 000 -

Extensions of Remarks. Hon. Donald M. Fraser

February 19, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 4031 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS. AID FOR BIAFRAN CHILDREN be known as the "Ravensbrueck Lapins" tions. On the basis of his first-hand obser was of a dual nature. One aspect was to bring vations, Mr. Cohen spoke of growing problems them to the United States for medical and confronting evacuation of children by air. HON. DONALD M. FRASER surgical care. The other aspect was to obtain He brought U3 together with Mr. G. A. On Oi' MINNESOTA from the German government at Bonn ade yegbula, Permanent Secretary of Biafra, who quate compensation that would enable them had just arrived in New York on a brief gov IN THE HOUSE OP REPRESENTATIVES to live Without continued and excessive hard ernment mission. Mr. Onyegbula spoke of the Tuesday, February 18, 1969 ship. Both these parts of the project were severity of Biafra's needs. Two thousand carried out. children and 4,000 adults were dying daily Mr. FRASER. Mr. Speaker, one of the The editors now invite the readers of SR of starvation. Food and medical supplies most remarkable humanitarian efforts to join them in a fourth project. It is called were being flown into Bia.fra In larger quan directed at relieving the misery of the ABc-Aid for Biafran Children. HereWith, tities than had been possible for some Nigerian-Biafran tragedy is known as some background. months. But the situation continued to be Aid for Biafran Children-ABC. Last September, when the food blockade of critical and was apt to remain that way Biafra was at its worst, and when thousands until there was a dramatic breakthrough in One of the principals in this effort is of children were dying from protein shortage, direct access. -

Headspace Gas Analysis of Salad Oils by Mass Spectrometry

Reprinted from tbe JOUR_ AL OF THE AMERICAN OIL CHEMISTS' SOCIETY, Vol. 49, No.2, Pages: 106--110 (February 1972) Purcbased by U.S. Dept. of Agriculture for Official Use. Headspace Gas Analysis of 3086 Salad Oils by Mass Spectrometry C.D. EVANS and E. SE LKE, Northern Regional Research Laboratory,' Peoria, Illinois 61604 ABSTRACT In this report we present a reliable sampling technique A mass spectrometer was used to analyze the and data on headspace gas analysis of several commercially content of hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, carbon diox processed vegetable salad oils packaged in glass bottles. ide and argon in headspace gas of commercially packaged soybean, cottonseed and corn salad oils. A EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE leakproof sampling system was designed to avoid air contamination and obtain a representative headspace Salad oils packaged in pint and 1.5 pint screw cap gas sample. Some edible oils are packaged under pure bottles came from retail stores, from warehouses, direct nitrogen, whereas other samples contained various from the processors, and in one plant directly off the amounts of oxygen in the headspace gas. The bottling line. Upon receipt of all bottles, some were held at presence or absence of argon in the headspace gas 34 F and others were frozen at 0 F until analyzed or placed indicates that some oils are packaged with pure under accelerated storage conditions. Part of the samples nitrogen and others with nitrogen obtained by con obtained directly from the bottling line were frozen trolled burning of hydrocarbons to remove all the immediately and transported in dry ice. The frozen samples oxygen in air. -

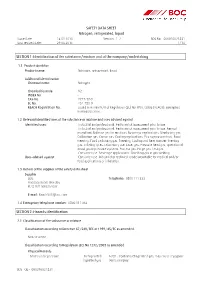

SECTION 1: Identification of the Substance/Mixture and The

SAFETY DATA SHEET Nitrogen, refrigerated, liquid Issue Date: 16.01.2013 Version: 1. 2 SDS No.: 000010021831 Last revised date: 29.06.2015 1/13 SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1 Product identifier Product name: Nitrogen, refrigerated, liquid Additional identification Chemical name: Nitrogen Chemical formula: N2 INDEX No. - CAS-No. 7727-37-9 EC No. 231-783-9 REACH Registration No. Listed in Annex IV/V of Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 (REACH), exempted from registration. 1.2 Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Identified uses: Industrial and professional. Perform risk assessment prior to use. Industrial and professional. Perform risk assessment prior to use. Aerosol propellant. Balance gas for mixtures. Beverage applications. Blanketing gas. Calibration gas. Carrier gas. Cooling applications. Fire suppressant gas. Food freezing. Food packaging gas. Freezing, Cooling and heat transfer. Inerting gas. Inflating tyres. Laboratory use. Laser gas. Pressure head gas, operational assist gas in pressure systems. Process gas. Purge gas. Test gas. Consumer use. Beverage applications. Shielding gas in gas welding. Uses advised against Consumer use. Industrial or technical grade unsuitable for medical and/or food applications or inhalation. 1.3 Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Supplier BOC Telephone: 0800 111 333 Priestley Road, Worsley M28 2UT Manchester E-mail: [email protected] 1.4 Emergency telephone number: 0800 111 333 SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1 Classification of the substance or mixture Classification according to Directive 67/548/EEC or 1999/45/EC as amended. Not classified Classification according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 as amended.