Understanding Video Game Music Tim Summers , Foreword by James Hannigan Frontmatter More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concert Review: Symphony Help Breathe Life Into Video Games | Deseret News

11/23/2016 Concert review: Symphony help breathe life into video games | Deseret News Family Concert review: Symphony help breathe life into video games By Scott Iwasaki Published: March 29, 2008 12:00 a.m. "VIDEO GAMES LIVE!" Utah Symphony, Abravanel Hall, Friday, additional performance today, 355-2787 With strobe lights, a big video screen, mirror balls and an electric guitar, it was clear that "Video Games Live!" is not a typical symphony concert. And to have the Utah Symphony give two acts of video-game music life in a place other than the TV was nothing short of a rush. By the end of the show, the symphony did exactly what narrator and game composer and "Video Game Live!" co-founder Tommy Tallarico said it would do — "Show how culturally significant video games and video game music is in the world today." Conducted by video-game-music composer and "Video Game Live!" co-founder Jack Wall, the symphony, aided by the Snow College Choir, took the nearly sold-out audience on a journey from the early days of video gaming to the present. Kicking off the evening with the "blip-bleep" of "Pong" and ending with a rousing crescendo of "Final Fantasy VII," the concert brought old and young gamers together. With a symphonic suite, the concert highlighted pioneering games such as "Donkey Kong," "Dragon's Lair," "Tetris," "Frogger" and "Space Invaders," to name a few. In keeping with the "Space Invaders" theme, Tallarico chose a member from the audience to play a giant screen version of the game while the symphony performed the theme. -

Abstract the Goal of This Project Is Primarily to Establish a Collection of Video Games Developed by Companies Based Here In

Abstract The goal of this project is primarily to establish a collection of video games developed by companies based here in Massachusetts. In preparation for a proposal to the companies, information was collected from each company concerning how, when, where, and why they were founded. A proposal was then written and submitted to each company requesting copies of their games. With this special collection, both students and staff will be able to use them as tools for the IMGD program. 1 Introduction WPI has established relationships with Massachusetts game companies since the Interactive Media and Game Development (IMGD) program’s beginning in 2005. With the growing popularity of game development, and the ever increasing numbers of companies, it is difficult to establish and maintain solid relationships for each and every company. As part of this project, new relationships will be founded with a number of greater-Boston area companies in order to establish a repository of local video games. This project will not only bolster any previous relationships with companies, but establish new ones as well. With these donated materials, a special collection will be established at the WPI Library, and will include a number of retail video games. This collection should inspire more people to be interested in the IMGD program here at WPI. Knowing that there are many opportunities locally for graduates is an important part of deciding one’s major. I knew I wanted to do something with the library for this IQP, but I was not sure exactly what I wanted when I first went to establish a project. -

LAMPIRAN 1. Prosedur Install PC Wizard • Klik Kanan Pada “Pc-Wizard 2010.1.94”, Lalu Pilih “Extract Here”. • Lalu Kl

LAMPIRAN 1. Prosedur Install PC Wizard • Klik kanan pada “pc-wizard_2010.1.94”, lalu pilih “Extract Here”. • Lalu klik 2 kali pada PC Wizard • Lalu kita pilih video • Setelah itu klik Video Card untuk melihat Pixel Shader Version yang ada. Daftar Game yang direkomendasikan • Alexander • Act of War : Direct Action • Advent Rising • Attack on Perl Harbour • Battlestation : Midway • Black & White 2 • Black & White 2 : Battle of the Gods • Blood Rayne 2 • Boiling Point : Road to Hell • Brothers in Arms : Earned in Blood • Brothers in Arms : Road to Hill 30 • Caesar IV • Call of Cthulhu : Dark Corner of The Earth • Choatic • The Chronicles of Narnia : The Lion • The Chronicles of Riddick : Escape from Butcher Bay • Colin McRae Rally 2005 • Compony of Heroes • Darkstar One • Deus Ex : Invisible War • Devil May Cry 3 • Earth 2160 • Empire Earth 2 • Empire Earth 2 : The Art of Supremacy • Eragon • Fable : The Lost Chapters • F.E.A.R. • Half-Life 2 : Episode Two • Heroes of Might and Magic V • Heroes of Might and Magic V : Hammers of Fate • Heroes of Might and Magic V : Tribes of The East • Just Cause • Knight of The Temple 2 • Lego Stars Wars : Video Game • Lego Stars Wars II : The Original Trilogy • Lord of The Ring Online • Lord of The Ring : The Return of The King • Marck Ecko’s Getting Up : Contents Under Pressure • Marvel : Ultimate Alliance • Medal of Honor : Pacific Assault • Medievel II : Total War • Medievel II : Total War Kingdoms • Mega Man X8 • Need fo Speed Carbon • Paws & Claws Pet Vet 2 Healing Hands • Pirates of The Caribbean -

Theme Park World Manual Windows English

Warning: To Owners Of Projection Televisions Still pictures or images may cause permanent picture-tube damage or mark the phosphor of the CRT. Avoid repeated or extended use of video games on large-screen projection televisions. Epilepsy Warning Please Read Before Using This Game Or Allowing Your Children To Use It. Some people are susceptible to epileptic seizures or loss of consciousness when exposed to certain flashing lights or light patterns in everyday life. Such people may have a seizure while watching television images or playing certain video games. This may happen even if the person has no medical history of epilepsy or has never had any epileptic seizures. If you or anyone in your family has ever had symptoms related to epilepsy (seizures or loss of consciousness) when exposed to flashing lights, consult your doctor prior to playing. We advise that parents should monitor the use of video games by their children. If you or your child experience any of the following symptoms: dizziness, blurred vision, eye or muscle twitches, loss of consciousness, disorientation, any involuntary movement or convulsion, while playing a video game, IMMEDIATELY discontinue use and consult your doctor. Precautions To Take During Use ¥ Do not stand too close to the screen. Sit a good distance away from the screen, as far away as the length of the cable allows. ¥ Preferably play the game on a small screen. ¥ Avoid playing if you are tired or have not had much sleep. ¥ Make sure that the room in which you are playing is well lit. ¥ Rest for at least 10 to 15 minutes per hour while playing a video game. -

In Re: Majesco Securities Litigation 05-CV-3557-Amended Consolidated

Lisa J. Rodriguez TRUJILLO RODRIGUEZ & RICHARDS, LLC 8 Kings Highway West Haddonfield, NJ 08033 Tel : (856) 795-9002 Fax : (856) 795-9887 -and- Robert N. Kaplan Donald R. Hall Jeffrey P. Campisi KAPLAN FOX & KILSHEIMER LL P 805 Third Avenue, 22nd Floor New York, NY 10022 Tel : (212) 687-1980 Fax: (212) 687-771 4 Attorneysfor Lead PlaintiffDiker Management, LLC, Diker Micro and Small Cap Fund LP, Diker M&S Cap Master LTD, Diker Micro- Value Fund LP and Diker Micro Value QP Fund LP (" Diker ") [Additional counsel listed on signature page] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSE Y CASE NO. 2 :05-cv-03557-FSH-PS In Re Majesco Securities Litigation AMENDED CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION COMPLAIN T JURY TRIAL DEMANDED TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 . NATURE OF THE CLAIMS . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .......... .. ............ .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE . .. .......................... .......................... .... .. .. .. .. .. .... ........... 5 III. CLAIMS AGAINST DEFENDANTS UNDER §§ 11, 12, AND 15 OF THE SECURITIES ACT ....... .. ...................... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ............................ ............ .. .... 5 A. Securities Act Plaintiffs ............... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... ................ .... .. .. .. 5 B. Securities Act Defendants .......... .. .. .... .... ...... .. 6 C. Majesco's Registration Statement . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .9-1 7 IV . SECURITIES ACT COUNTS . .. .17-20 V. CLAIMS AGAINST DEFENDANTS UNDER § 10(b) AND RUL E 10(b)-5 AND UNDER § 20(a) OF THE EXCHANGE ACT . -

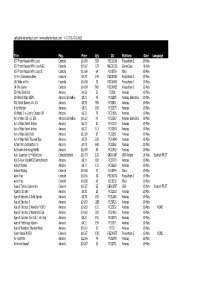

[email protected] +1 (718) 701 2662 Title Pkg. Price Qty ID Platform Date Language 007 from Russ

[email protected] www.entertainbest.com +1 (718) 701 2662 Title Pkg. Price Qty ID Platform Date Language 007 From Russia With Love Console $14.68 358 PS201240 Playstation 2 10-May 007 From Russia With Love NGC Console $15.67 129 NGC20136 GameCube 10-May 007 From Russia With Love SE Console $12.69 64 XB10259 XBox 10-May 10 Pin Champions Alley Console $9.70 149 PS200383 Playstation 2 10-May 187 Ride or Die Console $14.68 30 PS200453 Playstation 2 10-May 24 The Game Console $14.68 860 PS200805 Playstation 2 10-May 3D Pets Sold Out Amaray $4.23 21 50018 Amaray 10-May 3D World Atlas SIEPC Amaray SierraBox $8.71 45 PC32285 Amaray SierraBox 10-May 501 Great Games Vol. 18 Amaray $5.72 350 PC32831 Amaray 10-May 8:th Wonder Amaray $8.71 189 PC32575 Amaray 10-May AA Make It + Comic Creator DP Amaray $6.22 79 PC31906 Amaray 10-May Act of War Coll. Ed. SIE Amaray SierraBox $16.67 42 PC32587 Amaray SierraBox 10-May Act of War Direct Action Amaray $6.72 87 PC31172 Amaray 10-May Act of War Direct Action Amaray $6.72 513 PC32560 Amaray 10-May Act of War Gold Pack Amaray $12.69 67 PC32561 Amaray 10-May Act of War High Treason Exp. Amaray $9.70 230 PC31484 Amaray 10-May Action Man Destruction X Amaray $4.73 649 PC32562 Amaray 10-May Activision Anthology ReMix Amaray $12.69 64 PC31932 Amaray 10-May Adv. Guardian H. Mint/sticker Console Refurb $10.70 132 GBA10667 GBA Refurb 10-May Spanish FR IT Adv.3-Pack BlackM/J2Centre/Watch Amaray $8.71 650 PC32729 Amaray 10-May Advent Rising Amaray $8.71 131 PC30680 Amaray 10-May Advent Rising Console $14.68 37 XB10294 XBox 10-May Aeon Flux Console $18.66 28 PS200878 Playstation 2 10-May Aeon Flux Console $14.68 40 XB10532 XBox 10-May Agassi Tennis Generation Console $16.67 22 GBA10597 GBA 10-May Spanish FR IT Agatha Christie Amaray $9.70 25 PC32133 Amaray 10-May Age of Empires 1 Gold Xplosiv Amaray $6.72 183 PC31286 Amaray 10-May Age of Empires 3 Amaray $24.63 1188 PC30826 Amaray 10-May Age of Empires 3 Warchief NORD Amaray $24.63 125 PC32532 Amaray 10-May NORD Age of Empires 3 Warchiefs Exp. -

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1 Gabriel Huber Jun 05, 2018 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Authentication..............................................3 1.2 Account Management..........................................5 1.3 Listing.................................................. 21 1.4 Store................................................... 25 1.5 Reviews.................................................. 27 1.6 GOG Connect.............................................. 29 1.7 Galaxy APIs............................................... 30 1.8 Game ID List............................................... 45 2 Links 83 3 Contributors 85 HTTP Routing Table 87 i ii GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 Welcome to the unoffical documentation of the APIs used by the GOG website and Galaxy client. It’s a very young project, so don’t be surprised if something is missing. But now get ready for a wild ride into a world where GET and POST don’t mean anything and consistency is a lucky mistake. Contents 1 GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Authentication 1.1.1 Introduction All GOG APIs support token authorization, similar to OAuth2. The web domains www.gog.com, embed.gog.com and some of the Galaxy domains support session cookies too. They both have to be obtained using the GOG login page, because a CAPTCHA may be required to complete the login process. 1.1.2 Auth-Flow 1. Use an embedded browser like WebKit, Gecko or CEF to send the user to https://auth.gog.com/auth. An add-on in your desktop browser should work as well. The exact details about the parameters of this request are described below. 2. Once the login process is completed, the user should be redirected to https://www.gog.com/on_login_success with a login “code” appended at the end. -

Tekan Bagi Yang Ingin Order Via DVD Bisa Setelah Mengisi Form Lalu

DVDReleaseBest 1Seller 1 1Date 1 Best4 15-Nov-2013 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 1 1-Dec-2014 1 Seller 1 2 1 Best1 1 30-Nov-20141 Seller 1 6 2 Best 4 1 9 Seller29-Nov-2014 2 1 1 1Best 1 1 Seller1 28-Nov-2014 1 1 1 Best 1 1 9Seller 127-Nov-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 326-Nov-2014 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 1 25-Nov-20141 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 24-Nov-2014Best1 1 1 Seller 1 2 1 1 Best23-Nov- 1 1 1Seller 8 1 2 142014Best 3 1 Seller22-Nov-2014 1 2 6Best 1 1 Seller2 121-Nov-2014 1 2Best 2 1 Seller8 2 120-Nov-2014 1Best 9 11 Seller 1 1 419-Nov-2014Best 1 3 2Seller 1 1 3Best 318-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 17-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 1 1 Best 1 1 16-Nov-20141Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 15-Nov-2014 1 1 1Best 2 1 Seller1 1 14-Nov-2014 1 1Best 1 1 Seller2 2 113-Nov-2014 5 Best1 1 2 Seller 1 1 112- 1 1 2Nov-2014Best 1 2 Seller1 1 211-Nov-2014 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best110-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 2 Best1 9-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 18-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 3 2Best 17-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 6-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 2 1 Best1 4-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 14-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 13-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 1 13-Nov-2014Best 1 1 Seller1 1 1 Best12-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 2-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 3 1 1 Best1 1-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best5 1-Nov-20141 2 Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 31-Oct-20141 1Seller 1 2 1 Best 1 1 31-Oct-2014 1Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 31-Oct-2014Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 Seller 131-Oct-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 30-Oct-20141 1 Best 1 3 1Seller 1 1 30-Oct-2014 1 Best1 -

Game Developer

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS KAYDARA MOTIONBUILDER 5.5 * RONINWORKS BURSTMOUSE JUNE/JULY 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>E3 2004: PSP AND DS >>OUR LITTLE SECRET >>FEEDBACK LOOPS WHEN HANDHELDS OFFSHORE REAL-WORLD CONTROL COLLIDE OUTSOURCING FOR GAMES POSTMORTEM: THE CONTROL SYSTEM OF EA SPORTS FIGHT NIGHT 2004 []CONTENTS JUNE/JULY 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 6 FEATURES 14 OUR LITTLE SECRET: OFFSHORE OUTSOURCING Developers don’t want to talk about it, and publishers don’t want to admit it, but elements of game production are increasingly being sent abroad. Game journalist Dean Takahashi drills down, separating fact from fiction, and discovers sides to the story that make it less cut and dried than you might think. By Dean Takahashi 18 FEEDBACK LOOPS: IMPLEMENTING REAL-WORLD CONTROL SYSTEMS 14 Instead of throwing more algorithms or equations at a movement problem, one lone programmer came up with applying the real- world control mechanics of feedback loops in ZOO TYCOON 2. Read on, and see if it works for your game. 28 By Terence J. Bordelon 18 24 DOING MUSHROOMS, MIYAMOTO- POSTMORTEM STYLE Many of you reading this sentence were inspired to join the industry because of 28 EA SPORTS FIGHT NIGHT 2004 Shigeru Miyamoto. A much smaller and ever Ever notice that boxing games never really felt right? The team at EA luckier number also gets to work with him. 24 Chicago did, and figured out that the disconnect was in the traditional We recently talked with the man himself, button-pressing control scheme. But how do you work beyond people’s along with rising Nintendo stars Eiji Aonuma expecations? What can you do with control to make a game more fun? and Ken’ichi Sugino, and were rewarded with EA’s breakthrough with the Total Punch Control system might kindle much more than a pixellated princess by the some ideas. -

Games Pc Sim Theme Park Instruction Manual

Games Pc Sim Theme Park Instruction Manual To ensure they are kept for prosperity I repeat the instructions here, but all credit is due to You should then see a menu allowing you to install the game. So, first step is to navigate to the TPW / Sim Theme Park folder on your pc - once there. It states on the manual that it runs on Windows 95/98/me but not on Windows NT/2000 I've got Sim Theme Park installed on this computer, so why can't I get Sim Virtual PC for Windows 7 is free, I believe, but the Winodws98 copy is not free. game but are having issues, uninstall it and reinstall using these instructions. In the game, the player controls Jurassic Park's director of operations, who must III: Park Builder is similar to Sim and God games such as SimCity and Theme "Jurassic Park 2: The Chaos Continues (SNES) Instruction Manual" (PDF). Section 2, some DC/PS1/PS2/GCN/Wii/DS games Sim Theme Park (PS1) - $10 Sims 4 PC Origin Digital Code (U.S.) - $25 an over the moon request, but I'm looking for an instruction manual for the U.S. SNES version of Final Fight Guy. Sim Theme Park is my favorite childhood game and this fix allows you to play it. RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 – Triple Thrill Pack is an incredible simulation game Zoo Tycoon 2. free download theme park pc game. witcher no cd crack though it did require me to refer to the instruction manual for guidance more than once. -

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 31 Jan 2011 16:39:03 UTC Contents Articles Alice Hoffman 1 Andre Norton 3 Andrea Seigel 7 Ann Brashares 8 Brandon Sanderson 10 Carl Hiaasen 13 Charles de Lint 16 Clive Barker 21 Cory Doctorow 29 Danielle Steel 35 Debbie Macomber 44 Francine Prose 53 Gabrielle Zevin 56 Gena Showalter 58 Heinlein juveniles 61 Isabel Allende 63 Jacquelyn Mitchard 70 James Frey 73 James Haskins 78 Jewell Parker Rhodes 80 John Grisham 82 Joyce Carol Oates 88 Julia Alvarez 97 Juliet Marillier 103 Kathy Reichs 106 Kim Harrison 110 Meg Cabot 114 Michael Chabon 122 Mike Lupica 132 Milton Meltzer 134 Nat Hentoff 136 Neil Gaiman 140 Neil Gaiman bibliography 153 Nick Hornby 159 Nina Kiriki Hoffman 164 Orson Scott Card 167 P. C. Cast 174 Paolo Bacigalupi 177 Peter Cameron (writer) 180 Rachel Vincent 182 Rebecca Moesta 185 Richelle Mead 187 Rick Riordan 191 Ridley Pearson 194 Roald Dahl 197 Robert A. Heinlein 210 Robert B. Parker 225 Sherman Alexie 232 Sherrilyn Kenyon 236 Stephen Hawking 243 Terry Pratchett 256 Tim Green 273 Timothy Zahn 275 References Article Sources and Contributors 280 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 288 Article Licenses License 290 Alice Hoffman 1 Alice Hoffman Alice Hoffman Born March 16, 1952New York City, New York, United States Occupation Novelist, young-adult writer, children's writer Nationality American Period 1977–present Genres Magic realism, fantasy, historical fiction [1] Alice Hoffman (born March 16, 1952) is an American novelist and young-adult and children's writer, best known for her 1996 novel Practical Magic, which was adapted for a 1998 film of the same name. -

2XL Supercross (1 Disk ) Racing 25 Tlife (1 Disk ) Action 3 in 1 Game

2XL Supercross (1 Disk ) Racing 25 TLife (1 Disk ) Action 3 in 1 Game for Kids (1 Disk ) Mini Game 3D Hunting 2010 Hunt Rare And Wild Animals (1 Disk ) Hunting Simulation 4Story (1 Disk ) MMORPG 4x4 Hummer (1 Disk ) Racing 7 Wonders - Treasures of Seven (1 Disk ) Action 7 Wonders 5 Ancient Alien Makeover (1 Disk ) Action 8 Crazy Chicken Collection (1 Disk ) Mini Game 9 - The Dark Side of Notre Dame (1 Disk ) Adventure 10 Moorhuhn Games (1 Disk ) Mini Game 99 Spirits (1 Disk ) RPG 1707 Great Games (1 Disk ) Mini Game 1953 - KGB Unleashed (1 Disk ) Adventure 15 Days (1 Disk ) Adventure 18 Wheels of Steel - Big City Rigs (1 Disk ) Simulation 18 Wheels of Steel - Across America (1 Disk ) Simulation 18 Wheels of Steel - American Long Haul (1 Disk ) Simulation 18 Wheels of Steel - Haulin (1 Disk ) Simulation 18 Wheels of Steel - Pedal To The Medal (1 Disk ) Simulation 51 Cartoon Network Games (1 Disk ) Mini Game 144 Mega Dash Collection (1 Disk ) Mini Game 150 Gamehouse Games (1 Disk ) Mini Game 300 Dwarves (1 Disk ) Tower Defense 400 Mini Games Amorosoo (1 Disk ) Mini Game 450 Games (PopCap, Gamehouse, Reflexive Arcade and Others) (1 Disk ) Mini Game 7554 (include all DLC) (1 Disk ) FPS 7.62 High Calibre (1 Disk ) Action 911 - First Responders (1 Disk ) Adventure 911 Paramedic (1 Disk ) Simulation A-GA (1 Disk ) Adult Games A Farewell to Dragons (1 Disk ) Action RPG A Game of Dwarves (1 Disk ) Strategy A Game of Thrones Genesis (1 Disk ) RTS A New Beginning (1 Disk ) Adventure A Stroke of Fate Operation Valkyrie (1 Disk ) Adventure A Train