Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Beyond 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

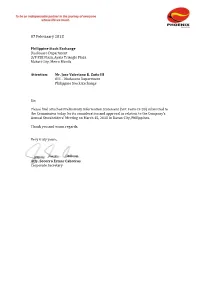

Preliminary Information Statement

07 Februaary 2018 Philippine Stock Exchange Disclosure Department 3/F PSE Plaza, Ayala Triangle Plaza Makati City, Metro Manila Attention: Mr. Jose Valeriano B. Zuño III OIC ‐ Disclosure Department Philippine Stock Exchange Sir: Please find attached Preliminary Information Statement (SEC Form IS‐20) submitted to the Commission today for its consideration and approval in relation to the Company’s Annual Stockholders’ Meeting on March 15, 2018 in Davao City, Philippines. Thank you and warm regards. Very truly yours, Atty. Socorro Ermac Cabreros Corporate Secretary Page 2 of 48 SEC Form IS-20 Page 3 of 48 SEC Form IS-20 PART I. INFORMATION REQUIRED IN INFORMATION STATEMENT A. GENERAL INFORMATION Item 1. Date, time and place of meeting of security holders (a) Date : March 15, 2018 Time : 2:00 p.m . Place : Phoenix Petroleum Corporate Headquarters Stella Hizon Reyes Rd. Davao City Mailing P-H-O-E-N-I-X PETROLEUM PHILIPPINES, INC. Address: Office of the Corporate Secretary Phoenix Petroleum Corporate Headquarters Stella Hizon Reyes Road, Bo. Pampanga Lanang, Davao City 8000 (b) Approximate date on which the Information Statement is first to be sent or given to security holders: February 22, 2018. Item 2. Dissenter ’s Right of Appraisal Procedure for the exercise of Appraisal Right Pursuant to Section 81 of the Corporation Code of the Philippines, a stockholder has the right to dissent and demand payment of the fair value of his shares in case of any amendment to the articles of incorporation that, (1) in case of amendment to the articles of incorporation, has the effect of changing or restricting the rights of any stockholder or class of shares, or of authorizing preferences in any respect superior to those of outstanding shares of any class, or of extending or shortening the term of corporate existence; (2) in case of lease, exchange, transfer, mortgage, pledge or other disposition of all or substantially all of the corporate property and assets as provided in the Corporation Code, and (3) in case of merger or consolidation. -

フィリピン共和国 (Republic of the Philippines )

フィリピン HTML 版 フィリピン共和国 (Republic of the Philippines) 通 信 Ⅰ 監督機関等 1 情報通信 技術 省 (DICT) Department of Information and Communications Technology Tel. +63 2 8920 0101 URL https://dict.gov.ph/ C. P Garcia Ave., Diliman, Quezon City, Metro Manila 1101, 所在地 PHILIPPINES 幹 部 Gregorio Ballesteros Honasan II(大臣/Secretary) 所掌事務 2016 年 6 月の 「 共 和 法第 10844 号」に基づき設立された。情報通信技術局 (Information and Communications Technology Office : ICTO ) や 国 際 コ ン ピュータ セ ン ター( National Computer Center:NCC)と いっ た 機 関が DICT に 統合され た ほ か、電気 通 信 委員 会(National Telecommunications Commiss ion : NTC)や国家プライバシー委員会( National Privacy Commission : NPC )等の 組織が付 属 機 関と さ れ た。 主な所掌 事 務 は、ICT 関 連 の 政策 立 案 、電 子政 府 等 の ICT 利 用 の促 進 、ICT 関 連の法整 備 で ある 。 2 電気通信 委員 会 ( NTC) National Telecommunications Commission Tel. +63 2 8924 4042 URL https://ntc.gov.ph/ NTC Bldg., BIR Road, East Triangle, Diliman, Quezon City 所在地 1104, PHILIPPINES 幹 部 Gamaliel A. Cordoba(委員長/Commissioner) 所掌事務 1979 年に「 大統 領 令 第 546 号 」に 基 づ き設 立 さ れた 。ガイ ド ラ イン 、規 則 を 策 1 フィリピン 定可能な独立規制機関であり、大統領府直属に設置されていたが、2016 年 6 月の 「共和法 第 10844 号 」に よ り、情 報通 信 技 術省 の 付 属機 関 と な った 。電 気 通 信 分 野における主な所掌事務は以下のとおりである。 ・電気通信設備及び電気通信サービスに関する規制、基準等の制定 ・電気通信事業の運営地域の設定及び電気通信料金の設定 ・無線局 及 び 電気 通 信 設備 の 管 理監 督 ・電気通 信 設 備・ 機 器 輸入 の 規 制、 法 執 行 Ⅱ 法令 公衆電気 通 信 政策 法 (Public Telecommunications Policy Act:PTPA、共和国法 第 7925 号 ) 1995 年 3 月に施行された。事業免許の付与条件、事業者の義務等が規定されて いる。電気通信設備を所有する電気通信事業者に、一定期間に一定数の加入者回 線の設置を義務付ける一方、設備を保有せずにサービスを提供する付加価値サー ビス事業者に対しては、電気通信市場への参入を原則自由とすること等を規定し ている。なお、同法には、法令違反を犯した通信事業者に対する罰則規定が存在 しないた め 、2019 年 10 月に NTC に対して違反者を処罰する権限を付与するた -

A Study Into the Proposed New Telecommunications Operator in the Philippines: Critical Success Factors and Likely Risks

A STUDY INTO THE PROPOSED NEW TELECOMMUNICATIONS OPERATOR IN THE PHILIPPINES: CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS AND LIKELY RISKS RELEASED: OCTOBER 2ND 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3. CHALLENGES OF BUILDING A NETWORK 4. A THIRD NATIONAL OPERATOR 5. BACKGROUND ON CHINA TELECOMMUNICATIONS 6. BACKGROUND ON UDENNA CORPORATION 7. SELECTION PROCESS 8. TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF LICENCE 9. RESOURCES NEEDED 10. RISK FACTORS 11. CONCLUSIONS 12. APPENDIX 1 1. INTRODUCTION The following report provides an in-depth analysis of the proposed entry of a third telecommunications operator in the Philippines. The report specifically looks at the critical success factors and likely risks involved. The report has been undertaken by specialist Asia Pacific consulting firm Creator Tech on behalf of private sector parties interested in the development of the telecommunications industry in the Philippines market. Creator Tech provides bespoke research and advisory services to public and private sector organisations on topics such as digital technologies, wireless networks, Internet of Things, Smart City planning and build-outs, telecommunications, broadband, data sharing and open data. The firm has been operating for over 15 years in Australia and across the region. 2 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Building a telecommunications network in the SOME OTHER KEY FACTS TO BE CONSIDERED: Philippines is extremely challenging. The country, for • The 40% non-Philippine partner in this third national example, is an archipelago of over 7,000 islands. telco, China Telecom, reports to the Central People’s Since the introduction of Globe Communications as a Government in China. challenger to the previous private monopoly of PLDT, • This partner was put forward after a request from much progress has been made, despite both the President Duterte to Li Keqiang, Premier of the State natural challenges and other ‘man-made’ challenges Council of the People’s Republic of China, for a third detailed below. -

Smart’ Morgan Mouton

Worlding infrastructure in the global South: Philippine experiments and the art of being ‘smart’ Morgan Mouton To cite this version: Morgan Mouton. Worlding infrastructure in the global South: Philippine experiments and the art of being ‘smart’. Urban Studies, SAGE Publications, 2021, 58 (3), pp.621-638. 10.1177/0042098019891011. hal-02977298 HAL Id: hal-02977298 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02977298 Submitted on 16 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Special issue article: Smart cities between worlding and provincializing Urban Studies 2021, Vol. 58(3) 621–638 Ó Urban Studies Journal Limited 2020 Worlding infrastructure in the global Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions South: Philippine experiments and DOI: 10.1177/0042098019891011 the art of being ‘smart’ journals.sagepub.com/home/usj Morgan Mouton University of Calgary, Canada Abstract This article explores the material dimensions of ‘smart city’ initiatives in the context of postcolo- nial cities where urban utilities are qualified as deficient. It argues that while such projects may very well be another manifestation of urban entrepreneurialism, they should not be dismissed as an already-outdated research object. -

SEC Number 808 File Number

SEC Number 808 File Number ________________________________________________ DITO CME HOLDINGS CORP. (Formerly: ISM COMMUNICATIONS CORP.) ________________________________________________ (Company’s Full Name) 21 st Floor, Udenna Tower Rizal Dr. cor. 4 th Avenue Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City, 1634 _________________________________________________ (Company’s Address) 8403 - 4007 ______________________________________ (Telephone Number) December 31 2019 (Fiscal Year Ending) (month & day) SEC Form 17-A (Annual Report) ______________________________________ Form Type ______________________________________ Amendment Designation (if applicable) December 31, 2019 ______________________________________ Period Ended Date N/A __________________________________________________ (Secondary License Type and File Number) 21 st Floor Udenna Tower, Rizal Drive corner 4 th Avenue, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City Philippines 1634 | Tel No.: (632) 84034007 SEC FORM 17-A 21 st Floor Udenna Tower, Rizal Drive corner 4 th Avenue, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City Philippines 1634 | Tel No.: (632) 84034007 ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF THE CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 2. SEC Identification Number 808 3. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-162-935V 4. DITO CME HOLDINGS CORP. (FORMERLY ISM COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION) Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter Philippines 5. Province, country or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization 6. Industry Classification Code: ___________________(SEC Use Only) 21st Floor, Udenna Tower Rizal Dr. cor. 4th Avenue Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City, 1634 7. Address of principal office (632) 8403-4007 1634 8. Registrant’s telephone number Zip Code ISM Communications Corporation, 3F Alegria Alta Building, 2294 Don Chino Roces Ave., Makati City 9. Former name, former address, and former fiscal year, if changed since last report 10. -

Dito Telecommunity Corporation: Challenging Telecom Duopoly in the Philippines

Journal of International Business Education 15: 331-346. © 2020 NeilsonJournals Publishing. Author Promo Version Dito Telecommunity Corporation: Challenging Telecom Duopoly in the Philippines Shweta Pandey De La Salle University, Philippines Sandeep Puri1 and Babak Hayati Asian Institute of Management, Manila, Philippines Abstract. Dito Telecommunity Corporation (Dito Telecom), the erstwhile Mislatel (Mindanao Islamic Telephone Company) Consortium, which won the government-sanctioned bid in the Philippines in mid-2019, is set to become the third major telco provider in the Philippines.2 In the run-up to its complete launch in early 2020, the telecom newbie started rolling out SIM cards to start pilot testing operations in November, struck deals with partners and competitors alike to access common towers, constructed new towers in key areas, built telco facilities in military camps, and even utilized unused fiber optic cables. However, the challenge ahead was to acquire and retain customers even as it tries to avoid a Php24 billion3 loss in the event it fails to fulfill its commitment of providing an Internet speed of 55 megabits per second (Mbps) covering 84% of the population over a 5-year period against a capital expenditure commitment of around Php250 billion4 and at the same time anticipate and counter obstacles in its quest to challenge the Globe–PLDT duopoly.5 Keywords: Telecom industry, customer-acquisition and customer retention, marketing strategy. 1. Lead Author declaration: This case has been written on the basis of published sources only. Consequently, the interpretation and perspectives presented in this case are not necessarily those of Mindanao Islamic Telephone Company or any of its employees. -

In West Philippine Sea Issue ABS-CBN News

Today’s News 02 May 2021 (Saturday) A. NAVY NEWS/COVID NEWS/PHOTOS Title Writer Newspaper Page DOD not dropping sputnik V despite brazil L Salaverria PDI A2 1 rejection; 15K doses arrive B. NATIONAL HEADLINES Title Writer Newspaper Page 2 Gov,t eyeing ₱8,000 monthly wages subsidy L Desiderio P Star 1 3 Tourism worker’s turn to receive cash aid M Ramos PDI A1 C. NATIONAL SECURITY Title Writer Newspaper Page 4 Palace blasts Carpio, other critics on WPS C Mendez PDI 1 5 West Philippine Sea ours to exploit – Solon J Manalastas P Journal 7 6 Ping pushes united tack on WPS M Gascon PDI A4 7 Lacson calls for unified stand on WPS issue M Purification P Tonight 6 8 United stand on WPS issue pressed M Purification P Journal 7 9 Gordon reminds Chinese envoy of Filipino L Ducusin P Journal 7 hospitality 10 ‘Di pagkakaisa ng mga Filipino sa isyu ng M Escudero Ngayon 2 WPS pinuna ni Lacson 11 Pacquiao pinapalayas ang China sa WPS M Escudero PM 2 D. INDO-PACIFIC Title Writer Newspaper Page NIL NIL NIL NIL E. AFP RELATED Title Writer Newspaper Page Salceda bill pushes pension reforms for J Aurelio PDI A2 12 uniformed services Cebu Mactan Airbase official defends Bong P Journal 13 13 Go over fake news Ngayon 2 14 Bong Go biktima ng ‘fake news’, idinepensa ng Cebu Mactan Airbase official Bong Go idinepensa sa fake news ng Cebu P Tonight 1 15 Mactan Airbase official 16 Sotto vows to retain NTF-ELCAC funds Y Terrazola M Bulletin 4 F. -

Public–Private Partnership Monitor: Philippines

Public–Private Partnership MonitorMonitor IndonesiaPhilippines This publication providespresents a snapshotdetailed overview of the overall of the public–private current state ofpartnership the public–private (PPP) landscape partnership in Indonesia. (PPP) Itenvironment includes more in the than Philippines. qualitative In over and three quantitative decades, theindicators country to developed profile the a national robust public–private PPP environment, thepartnership sector-specific (PPP) enabling PPP landscape framework (for eightthrough identified the Build-Operate-Transfer infrastructure sectors), Law and of the PPP and landscape the PPP for localCenter. government Among developing projects. Thismember downloadable countries ofguide the alsoAsian captures Development the critical Bank, macroeconomic the Philippines andhas a infrastructurerelatively mature sector market indicators that has (including witnessed the Ease financially of Doing closed Business PPPs. scores) Under from the government’s globally accepted sources. Through Presidential Development Regulation Plan that 38/2015, has an the infrastructure cornerstone investment of the country’s target robust of PPP billion, enabling PPPs framework, are Indonesiaexpected to expects play a PPPspivotal to role continue in financing playing national a pivotal and role subnational to achieve infrastructureits infrastructure investments. investment With target a ofpipeline billionof PPPs, for the government and mobilize is taking various of this steps value to further from the improve private the sector. environment for PPPs. About the Asian Development Bank About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, ADBwhile issustaining committed its toeorts achieving to eradicate a prosperous, extreme inclusive, poverty. resilient, Established and insustainable , it is ownedAsia and by the Pacific,members while— sustainingfrom the region. -

Doing Business in the Philippines Bucking the Global Slowdown, Building for the Future April 2019 Foreword

Doing business in the Philippines Bucking the global slowdown, building for the future April 2019 Foreword I would like to laud the efforts of Navarro Amper & Co.—one of the leading professional services firms in the country and a part of Deloitte's global network—for creating this investment guide to show investors that now is the best time to partner with the Philippines. The Philippines is on an economic breakout: it is the second fastest growing economy in Southeast Asia, with a GDP growth of 6.2 percent in 2018. The economy is projected to grow by 7 to 8 percent in the medium term. The main drivers for this growth are manufacturing and construction due to the influx of foreign investments in the country, and the government’s massive Build, Build, Build infrastructure program. Our Board of Investments (BOI) has registered record-breaking investment approvals for the past two consecutive years. In fact, the BOI approved Php915 billion worth of investments in 2018, with many of these in Mindanao, CALABARZON, and Central Luzon. These investments are set to bring more decent jobs and employment Ramon M. Lopez for Filipinos throughout the country. To ensure that these regions DTI Secretary become more accessible, the government is pushing its centerpiece infrastructure program to build more roads, ports, airports, and other structures to better link our country. The Duterte administration also put forward several legislative reforms including the Ease of Doing Business Law, the Rice Tarrification Law, the revision of the Corporation Code, and the proposed TRABAHO The Philippines: An overview 06 Bill. -

Issue No. 12, March 24, 2020

Volume 6 Issue No. 12 map.org.ph March 24, 2020 “MAPping the Future” Column in the INQUIRER BOUNCING BACK: Business Recovery and Continuity in Crisis Second of 2 Parts March 23, 2020 Usec. ALMA RITA “Alma” R. JIMENEZ BOUNCING BACK AND BUILDING RESILIENCE The Philippines is on the top 10 list of countries with highest risk for disasters and crisis. While COVID-19 is the immediate problem, we are warned that other disasters will occur with increasing frequency and severity, especially because of the climate change effect. Therefore, we ought to plan better, not only to bounce back from this crisis but to ensure that we build resilience into our systems. Though we had experienced similar crisis in the past, e.g. SARS, H1N1, MERS-COV etc., we seem to have not built on the lessons and come up with business recovery and continuity plans that would have been immediately activated when similar events recur. Yet today, we are still not prepared with our response mechanisms. Let the crisis we are experiencing today be the impetus to be more proactive. The forum yielded helpful suggestions from the subject experts, speakers, panelists and attendees summarized into these 3Ms: MITIGATE to lessen/palliate the immediate negative impact of the COVID-19. There are certain actions that can give quick wins, among them: • Counter the fears through better communication and greater transparency o There must be a regular, timely and factual information to feed news sources and other communication outlets. o Flood social media with good news; share recoveries rather than additional cases o Communicate better. -

Press Statement for New Appointments of Key Finance

23 March 2018 Securities & Exchange Commission Secretariat Building, PICC Complex Roxas Blvd, Metro Manila Philippine Stock Exchange Disclosure Department 3/F PSE Plaza, Ayala Triangle Plaza Makati City, Metro Manila Philippine Dealing & Exchange Corporation 37th Floor, Tower 1, The Enterprise Center 6766 Ayala Ave. corner Paseo de Roxas Makati, 1226 Metro Manila, Philippines Attention: Hon. Vicente Graciano P. Felizmenio, Jr. Director, Market and Securities Regulation Department Securities & Exchange Commission Mr. Jose Valeriano B. Zuño III OIC ‐ Disclosure Department Philippine Stock Exchange Ms. Vina Vanessa S. Salonga Head ‐ Issuer Compliance and Disclosure Department (ICDD) Gentlemen and Madam: Anent our announcement pertaining to the new appointments of key finance officers in the Company, we would like to submit the attached press statement for your reference. Thank you and warm regards. Very truly yours, Atty. Socorro Ermac Cabreros Corporate Secretary March 23, 2018 Phoenix Petroleum makes key finance appointments Phoenix Petroleum Philippines, Inc. has appointed Ms. Ma. Concepcion F. De Claro as the company’s new Chief Finance Officer (CFO), replacing Mr. Joseph John L. Ong, who will move to his new role as Treasurer and Head of Corporate Finance. The appointments are effective May 1, 2018, and were made in view of the company’s aggressive growth plans. Ms. De Claro has 36 years of extensive experience in financial management and corporate planning mainly with the energy and oil industry. She joined Phoenix’s parent company UDENNA Corporation in 2015 as Director of Mergers & Acquisitions. Prior to this, she was Chief Operating Officer of Alsons Corporation and a Director of Alsons Prime Investments Corporation and Alsons Power Holdings Corporation. -

“Business Resiliency and Innovation in a New Normal Era” 12 November 2020 Via Zoom Webinar

7TH SEC-PSE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE FORUM “Business Resiliency and Innovation in a New Normal Era” 12 November 2020 Via Zoom Webinar The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) have been conducting annual corporate governance (CG) forums since 2014 in line with their thrust to promote good CG to Philippine corporations. Current trends and developments in CG are considered in choosing the topics for the annual forum. This year, SEC and PSE recognize the importance of business resiliency and innovation to survive in this new era. Hence, with the theme “Business Resiliency and Innovation in a New Normal Era”, the 7th SEC-PSE CG Forum, to held in partnership with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), aims to be a platform to discuss the challenges brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic, and their impact on businesses and the economy as a whole. It is also an avenue to share and discuss response strategies and recovery approaches to combat the significant and adverse effects of the pandemic and how to hasten the country’s recovery. PROGRAM 8:00AM - 9:00AM Registration 9:00AM - 9:05AM Welcome Remarks Mr. Ramon S. Monzon President and CEO The Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. 9:05AM - 9:15AM Opening Remarks Atty. Emilio B. Aquino Chairperson Securities and Exchange Commission 9:15AM - 9:45AM Keynote Speech Mr. Karl Kendrick T. Chua Acting Socio-Economic Planning Secretary National Economic and Development Authority 9:45AM -11:15AM Topic 1: “CORPORATE GOVERNANCE IN THE NEW NORMAL” Background The Covid-19 global pandemic has critically impacted society, the health care industry, and consequently, the economy.