Smart’ Morgan Mouton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riders Digest 2019

RIDERS DIGEST 2019 PHILIPPINE EDITION Rider Levett Bucknall Philippines, Inc. OFFICES NATIONWIDE LEGEND: RLB Phils., Inc Office: • Manila • Sta Rosa, Laguna • Cebu • Davao • Cagayan de Oro • Bacolod • Iloilo • Bohol • Subic • Clark RLB Future Expansions: • Dumaguete • General Santos RIDERS DIGEST PHILIPPINES 2019 A compilation of cost data and related information on the Construction Industry in the Philippines. Compiled by: Rider Levett Bucknall Philippines, Inc. A proud member of Rider Levett Bucknall Group Main Office: Bacolod Office: Building 3, Corazon Clemeña 2nd Floor, Mayfair Plaza, Compound No. 54 Danny Floro Lacson cor. 12th Street, Street, Bagong Ilog, Pasig City 1600 Bacolod City, Negros Occidental Philippines 6100 Philippines T: +63 2 234 0141/234 0129 T: +63 34 432 1344 +63 2 687 1075 E: [email protected] F: +63 2 570 4025 E: [email protected] Iloilo Office: 2nd Floor (Door 21) Uy Bico Building, Sta. Rosa, Laguna Office: Yulo Street. Iloilo Unit 201, Brain Train Center City Proper, Iloilo, 5000 Lot 11 Block 3, Sta. Rosa Business Philippines Park, Greenfield Brgy. Don Jose, Sta. T:+63 33 320 0945 Rosa City Laguna, 4026 Philippines E: [email protected] M: +63 922 806 7507 E: [email protected] Cagayan de Oro Office: Rm. 702, 7th Floor, TTK Tower Cebu Office: Don Apolinar Velez Street Brgy. 19 Suite 602, PDI Condominium Cagayan De Oro City Archbishop Reyes Ave. corner J. 9000 Philippines Panis Street, Banilad, Cebu City, 6014 T: +63 88 8563734 Philippines M: +63 998 573 2107 T: +63 32 268 0072 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Subic Office: Davao Office: The Venue Bldg. -

Construction of up New Clark City – Phase 1 for the University of the Philippines

PHILIPPINE INTERNATIONAL TRADING CORPORATION National Development Company Building, 116 Tordesillas Street, Salcedo Village, 1227 Makati City CONSTRUCTION OF UP NEW CLARK CITY – PHASE 1 FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2020-271 Rebid (Previous Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2019-097) Approved Budget for the Contract: P 144,731,763.80 BIDS AND AWARDS COMMITTEE II FEBRUARY 2020 Philippine International Trading Corporation Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2020-271 REBID (PREVIOUS BID REF. NO. GPG-B2-2019-097) PHILIPPINE INTERNATIONAL TRADING CORPORATION National Development Company (NDC) Building, 116 Tordesillas Street, Salcedo Village, 1227 Makati City CONSTRUCTION OF UP NEW CLARK CITY – PHASE 1 FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Bid Reference No. GPG-B2-2020-271 REBID (Previous Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2019-097) Approved Budget for the Contract: P 144,731,763.80 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I. INVITATION TO BID…………………………................. 3 SECTION II. INSTRUCTIONS TO BIDDERS………………………… 6 SECTION III. BID DATA SHEET………………………………………. 31 SECTION IV. GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT…………… 43 SECTION V. SPECIAL CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT…………….. 73 SECTION VI. BIDDING FORMS………………………………………... 79 SECTION VII. POST-QUALIFICATION DOCUMENTS……………….199 SECTION VIII. SAMPLE FORMS…………………………………….…..202 SECTION IX. CHECKLIST OF REQUIREMENTS……………………207 Page 2 of 213 Construction of UP New Clark City – Phase 1 for the University of the Philippines Philippine International Trading Corporation Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2020-271 REBID Section I. Invitation to Bid Section I. Invitation to Bid (ITB) Page 3 of 213 Construction of UP New Clark City – Phase 1 for the University of the Philippines Philippine International Trading Corporation Bid Ref. -

Part 1 – BUSINESS and GENERAL INFORMATION Item 1

C O V E R S H E E T SEC Registration Number 1 7 0 9 5 7 C O M P A N Y N A M E F I L I N V E S T L A N D , I N C . A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S PRINCIPAL OFFICE ( No. / Street / Barangay / City / Town / Province ) 7 9 E D S A , B r g y . H i g h w a y H i l l s , M a n d a l u y o n g C i t y Secondary License Type, If Form Type Department requiring the report Applicable 1 7 - A C O M P A N Y I N F O R M A T I O N Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Number Mobile Number 7918-8188 No. of Stockholders Annual Meeting (Month / Day) Fiscal Year (Month / Day) 5,670 Every 2nd to the last Friday 12/31 of April Each Year CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Number/s Mobile Number Ms. Venus A. Mejia venus.mejia@filinvestg 7918-8188 roup.com CONTACT PERSON’s ADDRESS 79 EDSA, Brgy. Highway Hills, Mandaluyong City NOTE 1 : In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated 2 : All Boxes must be properly and completely filled-up. -

Business Directory Commercial Name Business Address Contact No

Republic of the Philippines Muntinlupa City Business Permit and Licensing Office BUSINESS DIRECTORY COMMERCIAL NAME BUSINESS ADDRESS CONTACT NO. 12-SFI COMMODITIES INC. 5/F RICHVILLE CORP TOWER MBP ALABANG 8214862 158 BOUTIQUE (DESIGNER`S G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG BOULEVARD) 158 DESIGNER`S BLVD G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG 890-8034/0. EXTENSION 1902 SOFTWARE 15/F ASIAN STAR BUILDING ASEAN DRIVE CORNER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION SINGAPURA LANE FCC ALABANG 3ARKITEKTURA INC KM 21 U-3A CAPRI CONDO WSR CUPANG 851-6275 7 MARCELS CLOTHING INC.- LEVEL 2 2040.1 & 2040.2 FESTIVAL SUPERMALL 8285250 VANS FESTIVAL ALABANG 7-ELEVEN RIZAL ST CORNER NATIONAL ROAD POBLACION 724441/091658 36764 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE EAST SERVICE ROAD ALABANG SERVICE ROAD (BESIDE STORE PETRON) 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE G/F REPUBLICA BLDG. MONTILLANO ST. ALABANG 705-5243 STORE MUNT. 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE UNIT 1 SOUTH STATION ALABANG-ZAPOTE ROAD 5530280 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE 452 CIVIC PRIME COND. FCC ALABANG 7-ELEVEN/FOODSTORE MOLINA ST COR SOUTH SUPERH-WAY ALABANG 7MARCELS CLOTHING, INC. UNIT 2017-2018 G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER 8128861 MUNTINLUPA CITY 88 SOUTH POINTER INC. UNIT 2,3,4 YELLOW BLDG. SOUTH STATION FILINVEST 724-6096 (PADIS POINT) ALABANG A & C IMPORT EXPORT E RODRIGUEZ AVE TUNASAN 8171586/84227 66/0927- 7240300 A/X ARMANI EXCHANGE G/F CORTE DE LAS PALMAS ALAB TOWN CENTER 8261015/09124 AYALA ALABANG 350227 AAI WORLDWIDE LOGISTICS KM.20 WEST SERV.RD. COR. VILLONGCO ST CUPANG 772-9400/822- INC 5241 AAPI REALTY CORPORATION KM22 EAST SERV RD SSHW CUPANG 8507490/85073 36 AB MAURI PHILIPPINES INC. -

IN the NEWS Strategic Communication and Initiatives Service

DATE: ____JULY _1________7, 2020 DAY: _____FRIDAY_ _______ DENR IN THE NEWS Strategic Communication and Initiatives Service STRATEGIC BANNER COMMUNICATION UPPER PAGE 1 EDITORIAL CARTOON STORY STORY INITIATIVES PAGE LOWER SERVICE July 17, 2020 PAGE 1/ DATE TITLE : DENR reaches 80% of full-year seedling target despite Covid -19 July 16, 2020, 7:19 pm MANILA – The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) on Thursday said it was able to raise some 36 million seedlings for the Enhanced National Greening Program (ENGP) during the first half of 2020 despite the coronavirus pandemic. The number already represents almost 80 percent of the 45.2 million seedlings targeted for the entire year under the government’s flagship reforestation program, DENR Secretary Roy Cimatu said in a media release, citing a report from the Forest Management Bureau (FMB). “This speaks well of how the DENR and its partners have carried out the ENGP in the face of challenges and constraints created by the pandemic,” Cimatu said. With this development, Cimatu said, the DENR is “on track” with its ENGP seedling production “just in time for planting this rainy season.” In its report, the FMB said the seedling production covers both plantation species and indigenous species used for rehabilitation of denuded areas in watershed, mangrove and protected areas. It also includes commodity species used for the establishment of agroforestry plantations. As of July 9, indigenous and plantation seedlings had reached 20 million; bamboo, 3.4 million; agroforestry, 2.98 million; fruit trees, 1.2 million; fuelwood, 796,600; rubber, 131,775; nipa, 65,000; and Ilang-ilang, 50,000. -

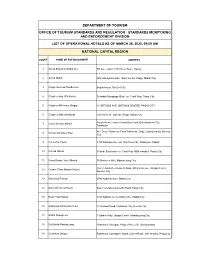

Standards Monitoring and Enforcement Division List Of

DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM OFFICE OF TOURISM STANDARDS AND REGULATION - STANDARDS MONITORING AND ENFORCEMENT DIVISION LIST OF OPERATIONAL HOTELS AS OF MARCH 26, 2020, 09:00 AM NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION COUNT NAME OF ESTABLISHMENT ADDRESS 1 Ascott Bonifacio Global City 5th ave. Corner 28th Street, BGC, Taguig 2 Ascott Makati Glorietta Ayala Center, San Lorenzo Village, Makati City 3 Cirque Serviced Residences Bagumbayan, Quezon City 4 Citadines Bay City Manila Diosdado Macapagal Blvd. cor. Coral Way, Pasay City 5 Citadines Millenium Ortigas 11 ORTIGAS AVE. ORTIGAS CENTER, PASIG CITY 6 Citadines Salcedo Makati 148 Valero St. Salcedo Village, Makati city Asean Avenue corner Roxas Boulevard, Entertainment City, 7 City of Dreams Manila Paranaque #61 Scout Tobias cor Scout Rallos sts., Brgy. Laging Handa, Quezon 8 Cocoon Boutique Hotel City 9 Connector Hostel 8459 Kalayaan Ave. cor. Don Pedro St., POblacion, Makati 10 Conrad Manila Seaside Boulevard cor. Coral Way MOA complex, Pasay City 11 Cross Roads Hostel Manila 76 Mariveles Hills, Mandaluyong City Corner Asian Development Bank, Ortigas Avenue, Ortigas Center, 12 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Quezon City 13 Discovery Primea 6749 Ayala Avenue, Makati City 14 Domestic Guest House Salem Complex Domestic Road, Pasay City 15 Dusit Thani Manila 1223 Epifanio de los Santos Ave, Makati City 16 Eastwood Richmonde Hotel 17 Orchard Road, Eastwood City, Quezon City 17 EDSA Shangri-La 1 Garden Way, Ortigas Center, Mandaluyong City 18 Go Hotels Mandaluyong Robinsons Cybergate Plaza, Pioneer St., Mandaluyong 19 Go Hotels Ortigas Robinsons Cyberspace Alpha, Garnet Road., San Antonio, Pasig City 20 Gran Prix Manila Hotel 1325 A Mabini St., Ermita, Manila 21 Herald Suites 2168 Chino Roces Ave. -

Sec 17-A Fy 2018

12. Check whether the issuer: (a) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 17 of the SRC and SRC Rule 17 thereunder or Section 11 of the RSA and RSA Rule 11(a)-1 thereunder, and Sections 26 and 141 of The Corporation Code of the Philippines during the preceding twelve (12) months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports); Yes [ X ] No [ ] (b) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past ninety (90) days. Yes [ X ] No [ ] 13. State the aggregate market value of the voting stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant. P1,931,103,029 as of December 31, 2018 APPLICABLE ONLY TO ISSUERS INVOLVED IN INSOLVENCY/SUSPENSION OF PAYMENTS PROCEEDINGS DURING THE PRECEDING FIVE YEARS: 14. Check whether the issuer has filed all documents and reports required to be filed by Section 17 of the Code subsequent to the distribution of securities under a plan confirmed by a court or the Commission. Yes [ ] No [X] DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE 15. If any of the following documents are incorporated by reference, briefly describe them and identify the part of SEC Form 17-A into which the document is incorporated: Consolidated Financial Statements as of and for year ended December 31, 2018 (Incorporated as reference for Item 7 to 12 of SEC Form 17-A) ________________________________________________________________________ CENTURY PROPERTIES GROUP INC. Page 2 of 84 SEC Form 17-A TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I. BUSINESS AND GENERAL INFORMATION 4 Item 1 Business……………………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Item 1.1 Overview…………………………………………………………………………. -

Biodiversity Assessment Study for New

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 50159-001 July 2019 Technical Assistance Number: 9461 Regional: Protecting and Investing in Natural Capital in Asia and the Pacific (Cofinanced by the Climate Change Fund and the Global Environment Facility) Prepared by: Lorenzo V. Cordova, Jr. M.A., Prof. Pastor L. Malabrigo, Jr. Prof. Cristino L. Tiburan, Jr., Prof. Anna Pauline O. de Guia, Bonifacio V. Labatos, Jr., Prof. Juancho B. Balatibat, Prof. Arthur Glenn A. Umali, Khryss V. Pantua, Gerald T. Eduarte, Adriane B. Tobias, Joresa Marie J. Evasco, and Angelica N. Divina. PRO-SEEDS DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION, INC. Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines Asian Development Bank is the executing and implementing agency. This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Biodiversity Assessment Study for New Clark City New scientific information on the flora, fauna, and ecosystems in New Clark City Full Biodiversity Assessment Study for New Clark City Project Pro-Seeds Development Association, Inc. Final Report Biodiversity Assessment Study for New Clark City Project Contract No.: 149285-S53389 Final Report July 2019 Prepared for: ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550, Metro Manila, Philippines T +63 2 632 4444 Prepared by: PRO-SEEDS DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION, INC C2A Sandrose Place, Ruby St., Umali Subdivision Brgy. Batong Malake, Los Banos, Laguna T (049) 525-1609 © Pro-Seeds Development Association, Inc. 2019 The information contained in this document produced by Pro-Seeds Development Association, Inc. -

CPGI Bond Prospectus | February 9, 2021

Century Properties Group Inc. (incorporated in the Republic of the Philippines) ₱2,000,000,000 with an Oversubscription Option of up to ₱1,000,000,000 Fixed Rate 3-Year Bonds due 2024 at 4.8467% p.a. Issue Price: 100% of Face Value Sole Issue Manager, Sole Lead Underwriter and Sole Bookrunner The date of this Prospectus is February 9, 2021. THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION HAS NOT APPROVED THESE SECURITIES OR DETERMINED IF THIS PROSPECTUS IS ACCURATE OR COMPLETE. ANY REPRESENTATION TO THE CONTRARY IS A CRIMINAL OFFENSE AND SHOULD BE REPORTED IMMEDIATELY TO THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION. Office Address Contact Numbers Century Properties Group Inc. Trunkline (+632) 7793-5500 21st Floor Pacific Star Building, Cellphone (+63917) 555-5274 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue corner Makati Avenue, www.century-properties.com Makati City 1200 Century Properties Group Inc. (the “Issuer” or the “Company” or “CPGI” or the “Group”) is offering Unsecured Peso-denominated Fixed-Rate Retail Bonds (the “Bonds”) with an aggregate principal amount of ₱2,000,000,000, with an Oversubscription Option of up to ₱1,000,000,000. The Bonds are comprised of 4.8467% p.a. three-year bonds. The Bonds will be issued by the Company pursuant to the terms and conditions of the Bonds on March 1, 2021 (the "Issue Date"). Interest on the Bonds will be payable quarterly in arrears; commencing on June 1, 2021 for the first Interest Payment Date and on March 1, June 1, September 1 and December 1 of each year for each Interest Payment Date at which the Bonds are outstanding, or the subsequent Business Day without adjustment if such Interest Payment Date is not a Business Day. -

Locsin Cites PGH As 'One of the Best Things' Imelda

L VOL. 585 NO. 17 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2021 THE EXPONENT OF PHILIPPINE PROGRESS SINCE 1900 IN METRO MANILA ₱18.00 By ELLSON A. QUISMORIO orruption in government exists. President Duterte admitted this dur- Duterte admits ing the pre-recorded “Talk to the Peo- ple” public briefing on Wednesday night, CSept. 15. He, however, clarified that the corrup- tion is not in the level of his Cabinet officials. “Meron. Meron sa gobyerno (It exists in corruption in gov’t government)... I would be lying if I say there is no corruption,” Duterte said during the public briefing that was aired Cabinet members absolved; Thursday morning, Sept. 16. “In some other offices now, agen- cies, departments, there are [in- audit of PH Red Cross pressed stances of corruption],” he said. 5 (Presidential photo) Airline firms seek increased mobility among fully vaccinated By ELLSON A. QUISMORIO Major airline groups have sought Presidential Adviser for Entrepre- neurship Joey Concepcion's help in airing their concerns to the gov- ernment regarding the impact of the protracted coronavirus dis- ease (COVID-19) pandemic on their TOURISM-READY — Tourism Secretary Bernadette businesses. Romulo-Puyat and Intramuros Administration Airline companies expressed (IA) chief Guiller Asido at Baluarte de San Diego worries that overly stringent travel in Intramuros inspect the preparations made by requirements imposed by both na- the IA for the opening of all its destination-worthy tional and local governments amid spots on the first day of the imposition of Alert the health crisis could lead to the Level 4 on the National Capital Region under the eventual crash of the local aviation new quarantine alert system on Thursday, Sept. -

Sec 17-A Fy 2019

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 SEC FORM 17-A OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF THE CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. For the fiscal year ended: December 31, 2019 2. SEC Identification Number: 60566 3. BIR Tax Identification No.: 004-504-281-000 4. Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter: CENTURY PROPERTIES GROUP INC. 5. Province, Country or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization: Philippines 6. Industry Classification Code: (SEC Use Only) 7. Address of principal office/Postal Code: 21st Floor, Pacific Star Building, Sen Gil Puyat Avenue corner Makati Avenue, Makati City 8. Issuer's telephone number, including area code: (632) 7938905 9. Former name, former address, and former fiscal year, if changed since last report: 10. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the SRC, or Sec. 4 and 8 of the RSA: Title of Each Class No. of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding and as Issued of December 31, 2018 COMMON 11,599,600,690 shares of stock outstanding 100,123,000 treasury shares PREFERRED 3,000,0000,000 11. Are any or all of these securities listed on a Stock Exchange. Yes [ X ] 11,699,723,690 common shares No [ ] If yes, state the name of such stock exchange and the classes of securities listed therein: Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. Common Shares 12. Check whether the issuer: (a) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 17 of the SRC and SRC Rule 17 thereunder or Section 11 of the RSA and RSA Rule 11(a)-1 thereunder, and Sections 26 and 141 of The Corporation Code of the Philippines during the preceding twelve (12) months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports); Yes [ X ] No [ ] (b) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past ninety (90) days. -

2020 Acas Website Updating.Xlsx

ASIA UNITED BANK CORPORATION List of Branches as of October 2020 NO. BRANCH NAME ADDRESS 1 168 MALL Unit 622-623, 6th Floor 168 Shopping Mall Soler Street Binondo, Manila 2 3RD AVENUE 154 - 158 Rizal Ave. Ext., Grace Park, Kalookan City 3 6780 AYALA G/F 6780 Ayala Avenue Building, 6780 Ayala Avenue, Makati City 4 999 MALL 3rd Floor, Unit P1-8, 999 Mall, Soler St. Binondo, Manila 5 ANGELES 351 Miranda St., Brgy. Sto Rosario, Angeles City 6 ANNAPOLIS GREENHILLS Unit 102, Intrawest Center, 33 Annapolis St., Greenhills, San Juan City 7 ANTIPOLO M.L. Quezon St., Brgy. San Roque, Antipolo City, Rizal 8 ANTIQUE RMU 2 Bldg., T.A. Fornier St., San Jose, Antique 9 ARRANQUE 692-694 T. Alonzo St. cor Soler St., Sta. Cruz, Manila 10 ASEANA CITY (PASAY MACAPAGAL AVE.) Macapagal Blvd., Brgy. Tambo, Paranaque City 11 AYALA ALABANG Madrigal Business Park cor. Commerce Ave. Alabang, Muntinlupa City 12 AYALA II G/F, Unit 1D, Multinational Bancorporation Center, 6805 Ayala Avenue, Makati City 13 BACLARAN G/F Parka Shopping Center, Park Ave. corner Kapitan Ambo St., Pasay City 14 BACOLOD G/F JS Bldg., Lacson St. cor. Galo St., Bacolod City, Negros Occidental 15 BACOLOD-BURGOS G/F ESJ Center Lot 1 Blk 5, Burgos St., Bacolod City 16 BACOOR 286 Rotonda Highway, P.F. Espiritu V., Bacoor, Cavite 17 BAGUIO G/F YMCA Bldg., Post Office Loop, Baguio City, Benguet 18 BALIBAGO 192 Diamond Hotel Bldg., McArthur Highway, Balibago, Angeles City 19 BALIUAG Li Bldg., 282 DRT Highway, Bagong Nayon, Baliuag, Bulacan 20 BANAWE 549 RBL Bldg.,Banawe St.